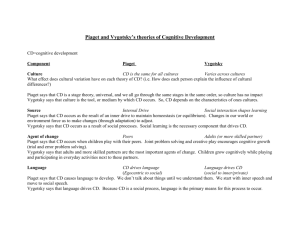

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315285086 Piagetian Versus Vygotskian Perspectives on Development and Education Conference Paper · April 1994 CITATIONS READS 3 8,981 1 author: R. Clarke Fowler Salem State University 17 PUBLICATIONS 130 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by R. Clarke Fowler on 17 March 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 1 Piagetian Versus Vygotskian Perspectives on Development and Education R. Clarke Fowler Education Department Salem State College Salem, MA 10970 Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, April 4, 1994. Author Notes I would like to thank Tom Bidell, Kathleen Camara, Sylvia Feinburg, David Feldman, and Michael Glassman for their comments on prior drafts of this article. Correspondence regarding this paper may be sent to the author either at Education Department, Salem State College, Salem, MA 01970 or via e-mail at: rfowler@salemstate.edu. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 2 Abstract This article contrasts the differing perspectives of Piaget and Vygotsky on a number of critical issues in intellectual development (i.e., the nature of intelligence, the relationship between thought and language, and the influence of social factors) and in education (i.e., the aims of education, the teacher-child relationship, the curriculum, vertical and lateral transfer, and the relationship between development and education). This effort was spurred by observations that recent research in the Vygotskian tradition--a tradition which many researchers have subscribed to in an effort to overcome some of Piaget's perceived limitations--appears to be moving, along some dimensions, back in the direction of Piaget. The question raised by this perceived shift in direction, though, is whether these two perspectives may be integrated? The aim of this article is to facilitate debate of this important question by mapping some of the theoretical ground such discussions will need to cover. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 3 Piagetian Versus Vygotskian Perspectives on Development and Education Over the last 30 years, Piaget has informed much of the research on child development in the United States. Within the last decade, though, as the social sciences have become increasingly concerned with understanding the impact of both culture and context on development and on education, the influence of Piaget has diminished while that of Vygotsky has risen. This shift has occurred, in part, because cultural and contextual influences are perceived as playing a major role in Vygotsky's account of development, but a minor role in Piaget's. Although contemporary Vygotskians have described many of the early attempts to flesh out the implications of Vygotsky's sociocultural approach as "one-dimensional," they have also noted and welcomed the emergence, "during the 1980's, [of] a broader and richer picture of the Soviet and sociohistorical school" (Minick, Stone & Forman, 1993, p. 5). It is interesting to note, however, that Contexts for development (Forman, Minick & Stone, 1993), the most recent effort to produce a "broader and richer" account of development from the sociocultural perspective, appears to Hatano (in his commentary on five of this volume's chapters) to lead back in the direction of Piaget: "There is a recognizable tendency ...to move away from transmission and toward constructivism" (1993, p. 163). The question raised by this perceived shift in direction is as follows: to what extent are the views of Piaget and Vygotsky compatible? Even if researchers are moving back in the direction of (Piagetian) constructivism, can these two perspectives really meet? This question, which has been considered by a number of writers in recent years, has produced a conflicting set of responses: some have portrayed their theories as complementary (Bearison, 1991; Forman & Kraker, 1985; Glassman, in press; Rogoff, 1988, 1990; Tudge & Rogoff, 1989, Tudge & Winterhoff, 1993; Zimmerman, 1993), others as conflicting (Bakhurst, Cole, Middleton & Nicolopoulou, 1988; DeVries & Zan, 1992; Downs & Liben, 1993; Forman, 1993; Wertsch, 1985; Wozniak, 1987). However the debate is resolved, it will have important implications for both research and practice. Yet, in order for a broad-based debate to take place, it will require that the nature of the differences that separate as well as the commonalities that unite these two thinkers be understood, not "from without", as Piaget wrote of his critics (Piaget in Chapman, 1988, p. 1), Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 4 but from within. Unfortunately, the works of both of these researchers have often been understood from without, and consequently, rejected--or even accepted--for the wrong reasons (Bidell, 1988, 1992). It is in order to facilitate mutual understanding and informed debate between the Piagetian and Vygotskian camps, therefore, that the current paper seeks to delineate a number of issues relevant to the compatibility of Piaget's and Vygotsky's perspectives on development and education. Since fully addressing both their differences and similarities is too large a task for one paper, however, this article will focus on their differences. Before proceeding, though, it is necessary to comment on the perils of this endeavor, perils which stem primarily from the limited availability of primary sources. In Vygotsky's case, a serious problem is presented by the fact that the bulk of his opus is still not available in English. This absence is largely due to the fact, for many years, his works were, for political reasons, not even available in Russian. Fortunately, his collected works have been published in Russian and are now appearing in English. Unfortunately, since only two of this projected six volume series has been printed in English, the bulk of his thought is still unavailable to those who, like the current author, do not read Russian. In Piaget's case, the problem is not that the bulk of his work is unavailable--indeed, a staggering number of books, articles, and essays are in existence in English--but that certain key texts have not yet appeared in English. Specifically, his sociological essays (Piaget, 1977) which address, among other topics, one of the most misunderstood aspects of his thought: the influence of social interaction on intellectual development. (These works are not scheduled to appear in English [Piaget, in press] until 1994.) Given the remarkable theoretical consistency of Piaget's work over the years (Chapman, 1988), though, the limited availability of one set of his essays is a relatively minor problem, especially when compared with the amount of Vygotsky's work that is still unavailable. Due to these limitations, the current paper seeks not so much to settle the debate over the (educational or psychological) compatibility of these two theories, as to map the territory to be covered in discussions between Vygotskians and Piagetians. In mapping out this terrain, however, my goal is not to adjudicate, but to explicate, in broad terms, some of the major differences separating Piaget and Vygotsky, beginning with their differing perspectives on intellectual development. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 5 Perspectives on Development Research Problems The principal problem addressed by Piaget concerned the formation of knowledge. His approach to this problem consisted of an elaboration of a scientific epistemology: As he saw it, epistemology calls for an interdisciplinary approach, while the main instrument for its construction resides in genetic psychology. Piaget replaced Emmanuel Kant's question "How is knowledge (e. g., pure mathematics) possible?" with this other question: "How is knowledge constructed and transformed in ontogenesis?" (Inhelder, 1992, p. xi, emphasis added) In other words, Piaget addressed a question drawn from the world of philosophy with tools forged in the realm of scientific psychology, and he called this enterprise genetic epistemology. At its heart, this novel endeavor sought an "explanation of what is new in knowledge from one stage of development to the next. How is it possible to attain something new?" (Bringuier, 1989, p. 19). Vygotsky addressed a very different kind of problem, one that is better described as cultural psychology than as genetic epistemology: Specifically, he sought "to specify how human mental functioning reflects and constitutes its historical, institutional, and cultural setting" (Wertsch, 1990, p. 115). Vygotsky felt that psychology could answer this question, but only by explaining consciousness; and a proper explanation of consciousness entailed specifying precisely how culture and context influence the "gradual reorganization of consciousness" (Lee, 1985, p. 71) within the individual. In brief, then, he wanted to understand the relationship between consciousness and culture--terms which Kozulin (1990) has characterized as the key elements of Vygotsky's theory. And his effort to understand the relationship between culture and consciousness led him to investigate specifically how human consciousness and functioning is raised to higher levels through the successful transmission of culturally developed mediational means of thought. For example, he attempted, in his research, to describe and explain how a child's level of intellectual functioning is qualitatively raised when she masters a social tool, such as speech, on an intrapsychological (i.e. internal) level. Thus, the problems investigated by Piaget and Vygotsky are related in that they both addressed issues that are crucial to any account of intellectual development; their approaches to these problems, however, differ in two important ways. First, they sought to explain different Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 6 moments in development: Piaget focused on the creation of new knowledge; Vygotsky, however, focused on the transmission and acquisition of preexisting tools of knowledge. Or, to put it briefly, Piaget was primarily interested in invention, and Vygotsky was primarily interested in transmission. Second, they were interested in different spheres of intellectual development. Vygotsky was interested in a narrow range of intelligence: namely, that which was uniquely human. What he wanted to explain, in part, was how humans--and only humans--raise themselves above their evolutionary animal ancestors through the acquisition, use, and mastery of sociohistorically evolved mental tools, such as language. By contrast, Piaget, who began his intellectual career as a biologist, was interested in a broad range of intelligence. That is to say, he was interested in intelligent behavior on the part of any living organism, be it plant or animal (1980a). Although most of his research was conducted with children, he was "convinced that there is no sort of boundary between the living and the mental, or between the biological and the psychological" (Bringuier, 1989, p. 3). This is not to say that Piaget wasn't interested in the highest achievements of human intelligence; indeed, he was passionately dedicated to explaining the origins of logic, mathematics, and science. One of his basic assumptions, though, was that the mechanisms of intelligent behavior (i. e., equilibration, assimilation, and accommodation) were, structurally speaking, the same at all levels of life. In fact, Cellerier (Bringuier, 1989) calls this one of Piaget's greatest insights. What is significant about the different problems they addressed, though, is not so much that these particular issues led them to consider different bodies of evidence--in fact, both wrote about research conducted with both human and non-human subjects--but that the problems they chose to investigate reveal their differing views on the nature of human intellectual development. For Piaget, qualitative changes in the aspects of cognition of interest to him are primarily the result of, but may not be reduced to, endogenous factors; for Vygotsky, however, qualitative changes in the aspects of cognition of interest to him are largely the result of, but may not be reduced to, exogenous factors. These contrasting views on the mechanisms of cognitive development are most salient in their respective accounts of the influence of social interaction on the development of human cognition. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 7 Social Influences on Human Intellectual Development One of the most misunderstood aspects of Piaget's work concerns the influence his theory assigned to social factors on development. Often he has been portrayed as giving, at best, a small role or, at worst, no role to social influences. Such criticisms of his work, however, are mistaken, as evidenced by the following excerpt from one his most important works, The Psychology of Intelligence (1966). The human being is immersed right from birth in a social environment which affects him just as much as his physical environment. Society, even more, in a sense, than the physical environment, changes the individual, because it not only compels him to recognize facts, but also provides him with a ready-made system of signs, which modify his thought (p. 156). It is crucial to note, however, that Piaget distinguished between two kinds of social factors: "[1] interactions or general social (or interindividual coordinations) that are common to all societies, and [2] transmissions or cultural and especially educative formations which vary from one society to another, or from one restricted social milieu to another" (Piaget, 1976a, p. 148, emphasis added). That is, he distinguished between the universal aspects of social interactions that occur in all cultures--"In every milieu, individuals gather information, collaborate, discuss, oppose one another, etc." (p. 148)--and the unique aspects of social events that occur in particular cultures. Since Piaget, as a genetic epistemologist, was interested in knowledge in general, as opposed to contextually or culturally specific knowledge, he studied social factors of the first kind: namely, the universal features of social interactions that children interiorize from social exchanges. And, in order to study the contribution of these universal features to intellectual development, to study what made the creation of knowledge possible in all contexts, he had to avoid studying it in specific contexts. Accordingly, he strived, in his research, "to strip away the effects of culture and to explore basic concepts in their 'uncontaminated' form" (Downs & Liben, 1993, p. 1993). Consequently, the fact that he consciously and purposely refrained from examining contextual factors shows, not that he minimized these factors, but, to the contrary, that "he did recognize the importance of sociocultural influences" (Downs & Liben, 1993, p. 179). If he actually believed that contextual factors had little or no influence on the development of knowledge, he would not have had to avoid these influences in the first place; nor would he have Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 8 stated that, without verification from cross-cultural research, genetic epistemology remained "essentially conjectural" (1976a, p. 160). Although specification of the many ways in which the universal aspects of social interaction contribute to the formation of cognitive structures is beyond the scope of this paper, it is worthwhile to mention one type that occurs between peers that is of particular importance; namely, cognitive conflict. When one child contradicts or opposes another's opinion, this often leads to cognitive disequilibrium, a disturbance that brings the child to reflect upon her world and, ultimately, spurs her to construct more adequate intellectual structures. It is because peer relations are rife with conflict among equals, the kind of conflict that leads to the creation of newer and more valid intellectual structures, that Piaget valued their contribution to intellectual (and also moral) development (1965). Such conflicts are among the most important of the universal aspects of social interaction that contribute to cognitive development. Contrary to many depictions of Piaget, then, social relations play not just an important, but a necessary role in his account of development. Social relations, however, play an even larger, indeed a truly formative role, in Vygotsky's account of development. To understand this role, however, it is important to digress for a moment to briefly describe what constituted cognitive development for Vygotsky in order to understand the role culture played in it. Vygotsky (1987) posited the existence of two lines of intellectual development within the child, the natural and the cultural. The products of the natural line were characterized as lower functions, and the products of the cultural line were characterized as higher functions. For Vygotsky, the key moment in child development occurs at around two years of age when these two lines cross and begin to interact with each other. This moment is so important because it marks the time when natural evolution begins to come under the control of the individual through the products of cultural evolution. For example, children's natural memory, a lower function, has a certain level of performance that it achieves naturally; however, when it comes under the control of a child via speech, it becomes logical memory, a higher function that is qualitatively superior to its natural incarnation. Since Vygotsky posits 1) that there are two lines of development, and 2) that qualitative advancement consists of moving from the lower natural level to the higher cultural level, then the key question he has to address is, in form, quite simple: How does this shift occur? His answer, Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 9 which gives a primary role to social factors, is found in his general genetic law of cultural development: Any function in the child's cultural development appears twice, or on two planes. First it appears on the social plane, and then on the psychological plane. First it appears between people as an interpsychological category, and then within the child as an intrapsychological category. (1981, p. 163) What this means, as Wertsch (1981) has pointed out, is not simply that "social interaction leads to the development [of children's higher functions]....rather he [Vygotsky] is saying that the very means (especially speech) used in social interaction are taken over by the child and internalized" (p. 146, emphasis added). In other words, the child's level of functioning is (qualitatively) heightened when she internalizes the (formerly) external means of social relations. It is important to note, however, that Vygotsky did not conceive of this process as an implantation of something new into the individual; rather, he wanted to portray this process as a reshaping (or restructuring) of that which the individual already possessed. In other words, social tools, introduced via social relations, don't create new abilities--"Culture creates nothing new" (1981, p. 166); instead, they transform children's preexisting (and continually developing) natural abilities by restructuring (or reorganizing) what they already possess. (Whether Vygotsky actually succeeded in portraying this process as restructuring, rather than as importing, is, of course, subject to debate and has even been questioned by his intellectual heirs [Wertsch & Tulviste, 1992], although Glassman [in press] argues that Vygotsky succeeded in this effort.) To summarize, social interactions are important for both Piaget and Vygotsky, but they are important for different reasons. For Piaget, they make a necessary contribution to the endogenous invention of new mental structures and schema. For example, children's social interactions, especially those with peers, are a rich source of cognitive conflict. They produce, within the individual, a state of disequilibrium which stimulates the creation of more powerful domain-general structures. For Vygotsky, however, social interactions are important because they lead to the appropriation (Rogoff, 1990) of culturally developed skills and functions. For example, children's interactions with adults enable them to acquire speech, a principal means of mastering the higher mental functions. Thus, social interactions are important for Vygotsky Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 10 because of what children take from them, and for Piaget because of what children make of them. The Relationship between Thought and Language Underlying the contrasting views presented by Piaget and Vygotsky on the influence of social factors in development is a dispute concerning the relationship between thought and language. Vygotsky holds that thought is qualitatively elevated when mediated by speech; Piaget holds that it is not. This dispute, which constitutes the basis of the only direct (albeit posthumous) intellectual exchange between these two theorists, will be considered below. In considering their differences, though, I shall not review the specific details of this exchange because Vygotsky's (1987) criticisms of Piaget's account of language have been (justifiably) questioned from both a Vygotskian (Wertsch, 1985) and a Piagetian (Brown, 1988) perspective. Instead, I shall focus on each theorists's account of the role of language (and speech) within his own theory. Vygotsky's account begins with the observation that children learn to speak by collaborating with adults in conversation. This constitutes, for him, an illustration of how a socially developed tool is not invented, but acquired, by the child. One of Vygotsky's greatest insights, though, was that the value of speech is not solely as an external tool of communication, but as an internal tool of self-regulation and reflection. In other words, the child appropriates speech from the social (intermental) realm and then applies this tool in a new realm, namely the individual (intramental) one. Thus, speech, which once mediated social thought, comes to mediate individual thought; and this new use of speech qualitatively raises the child's level of functioning. The specifically human capacity for language enables children to provide for auxiliary tools in the solution of difficult tasks, to overcome impulsive action, to plan a solution to a problem prior to its execution, and to master their own behavior. Signs and words serve children first and foremost as a means of social contact with other people. The cognitive and communicative functions of language then become the basis of a new and superior form of activity in children, distinguishing them from animals. (1978, 28-29) Speech becomes, on the intramental level, a "way of sorting out one's thoughts about things" (Bruner, 1986, p. 72). And it is this ability to sort things out that enables humans to effect the shift from the natural to the cultural level of development and gives human intellectual development its unique character. He concluded, therefore, that the use of speech on an Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 11 intramental level was the most important moment in cognitive development. The most significant moment in the course of intellectual development, which gives birth to the purely human forms of practical and abstract intelligence, occurs when speech and practical activity, two previously completely independent lines of development, converge. (1978, p. 24) Speech and language played a very different role in Piaget's account of development. Although he recognized that language was a very important component of human intellectual functioning, he did not give it the privileged position it plays in Vygotsky's theory. If it is legitimate to regard language as playing a chief role in the formation of thought, this is so to the extent that it constitutes one of the manifestations of the symbolical function, the development of the function being in turn dominated by intelligence in its total functioning. (Piaget, 1976b, p. 118) Thus, for Piaget, language was an important manifestation of what he called the symbolic (or semiotic) function, but this did not mean that language acquisition should be credited with the production of higher forms of knowledge. He would not dispute the fact that language enables one to have an internal dialogue, or to "sort things out;" but he would dispute the proposition that language can raise the level of functioning with which he was concerned: namely, the underlying intellectual structures of knowledge. In a word, language is not sufficient to transmit a logic, and it is only understood thanks to logical instruments of assimilation whose origin lies much deeper, since they are dependent upon the general coordination of actions of operations (1971, p. 40) For Piaget, language reflects, but does not produce, intelligence. The only way to advance to a higher intellectual level is, not through language, but through action. To summarize, Vygotsky felt that children appropriated from the social world mediational means of thought, and the most important of these means was speech. Once thought is mediated by speech on an internal level, the child's level of functioning is lifted up to a qualitatively higher level. Thus, just as men and women have transformed their outer physical world through the use of physical tools, such as the steel plow, so have they transformed their inner intellectual world though the use of mental tools, such as speech (Vygotsky, 1987). By contrast, Piaget did not grant mediational means of thought a special role in his account of development, not even to language. This is because he did not concede that language can lead to qualitative change in the overall structure of thought. For Piaget, "language is a product of Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 12 thought, rather than thought being a product of language" (1980b, p. 167). The Nature of Human Intelligence The final contrast between Piaget and Vygotsky to be considered in this section concerns their views on the nature of intelligence. For Piaget, intelligence was a unitary construct. He believed that intelligent behavior was subordinated to "general structures of the mind" (Gardner, 1983, p. 7); that the child's ability to understand is limited by the level of development of her intellectual structures, structures which constrain the child's abilities in all arenas. Equally important, he contended that these general structures of the mind developed in the same sequence, but not necessarily at the same rate, in all cultures. Vygotsky, however, did not advocate a unitary concept of intelligence. To the contrary, he contended that "the mind is not a complex of general capacities, but a set of specific capabilities" (1978, p. 83, cited in Cole, 1990, p. 92, emphasis added). The specific capabilities he envisioned were what he referred to as the higher mental functions, which included speech, mathematics, and writing. Moreover, these abilities were not universal, but culturally specific. Thus, although Piaget and Vygotsky both wrote about intellectual development, their notions of what develops in ontogenesis are quite different. For Piaget, mind is a domaingeneral intellectual structure that proceeds through the same stages in all settings. For Vygotsky, mind is a set of domain-specific abilities that are not universal but contextually and culturally specific. Summary In summarizing the differences outlined above between Piaget and Vygotsky, it is useful to consider how each would have treated the following extract in which Marx comments on the difference between man and nature. The spider carries out operations reminiscent of a weaver and the boxes which bees build in the sky could disgrace the work of many architects. But even the worst architect differs from the most able bee from the very outset in that before he builds a box out of boards he has already constructed it in his head. At the end of the work process he obtains a result which already existed in his mind before he began to build. The architect not only changes the form given to him by nature, within the constraints imposed by nature, he also carries out a purpose of his own which defines the means and the character of the activity to which he must subordinate his will. (Cited in Vygotsky, 1978, p. xiv) Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 13 Vygotsky, who frequently cited this excerpt from Marx, ascribed to the essential discontinuity that Marx posited between man and nature. In fact, Vygotsky felt that the goal of a truly human psychology was, in part, to explain how this separation from nature was achieved. His answer, in brief, was that by mastering the products of cultural evolution, those semiotic tools which are acquired in social interaction, the engineer is able to be planful, mindful, and volitional. Consequently, the engineer can build things mindfully, but the bee cannot. What is clear in this account is the large role that cultural tools play in raising humanity to higher levels of intellectual functioning. But what these tools ultimately make possible, though, is the capacity for conscious awareness of his own actions. And it is because the engineer is conscious of what he can do, and of what he wants to do, that he can master his actions. Thus, an expanded explanation of how man separates himself from nature is that it is through social interaction that man first becomes conscious of his actions and then, by actively appropriating and using (internally) the tools of social interaction, he gradually achieves control over the actions of which he has been made aware. Consequently, the discontinuity between man and nature is a direct product of human cultural evolution; and this discontinuity is sustained in the present via continued cultural transmission of a distinct and diverse set of semiotic tools that allow humanity to function at a high level in a variety of settings. What humanity ultimately achieves, though, thanks to the consciousness awareness achieved through the tools of culture, is self-regulation; but not the mindless self-regulation deeded by natural evolution, but the mindful self-regulation that can only be realized with the assistance of the products of cultural evolution. Piaget, who was more of a biologist than a psychologist, would have rejected the discontinuity that both Marx and Vygotsky drew between the bee and the engineer. Instead, he would have insisted on the basic continuity between these two biological organisms. This is not to say that he would deny that mediation contributes to man's planfulness, consciousness, or control; nor that he would deny that man can use semiotic tools to "sort things out." What he would challenge, though, is Vygotksy's reliance on consciousness as playing either a central or a formative role in higher level mental functioning. He would challenge this idea on two points: first, he would claim that Vygotsky is anthropocentric in claiming that only humans have consciousness (Bringuier, 1989); second, and most importantly, he would reject the notion that Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 14 merely raising one's consciousness can raise one's intellect. For Piaget, consciousness is subordinated to one's overall level of intellectual development. That is, we can only be aware of that which our intellectual structures allow us to be aware. (1976c, 1976d) For Piaget, the engineer becomes more capable than the bee, not due to the acquisition of conscious awareness of his own actions, but to the endogenous construction of a domain-general tool of intelligence; a tool that is spontaneously constructed through action, and not through language; a tool that actually makes possible the existence of the very same skills which Vygotsky valued; and, in the final analysis, a tool that is important, not because it leads to increasingly differentiated and organized levels of consciousness, but because it leads to increasingly valid forms of knowledge. A tool, in fact, that ultimately leads closer to truth. (Wartofsky, 1971, 1983) Clearly, then, Vygotsky and Piaget have produced very different accounts of both the nature and manner of human intellectual development. It is important to remember, however, that these accounts were produced in response to different research questions. Consequently, attempts to compare and contrast these views must be done with great care. As Glick has noted, "confusion is generated when theories are compared in terms of the mechanisms without at the same time understanding that the range of phenomena (the "facts") to which the theory applies is also different" (1983, p. 37). Glick's solution to this problem, when comparing three theories of development, was to consider the adequacy of each account with respect to a common domain, the investigation of the child. In an analogous manner, I shall proceed, in the following section, to compare the implications of their work for education. Perspectives On Education Although there is room for debate concerning the implications of Piaget and Vygotsky for education--debate both within and between the camps of their respective followers--there is no doubting the fact that each had serious objections to the traditional rote practices of their time. Although Piaget did not write frequently on education, when he did, he passionately condemned schools for their tendency to teach meaningless facts. He was disturbed by teachers who thought that their "task was not so much to form [the child's] mind as simply to furnish it" (1971a, p. 160). He characterized this kind of approach as the "enduring curse of education--verbalism" (1967, p. 14). Similarly, according to Van der Veer and Valsiner, Vygotsky also felt that a Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 15 teacher should not--indeed, could not--be a "provider of finished knowledge" (1991, p. 274): Pedagogical experience demonstrates that direct instruction in concepts is impossible. It is pedagogically fruitless. The teacher who attempts to use this approach achieves nothing but a mindless learning of words, an empty verbalism that stimulates or imitates the presence of concepts in the child. (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 170). Accordingly, Piaget and Vygotsky would both have agreed with Whitehead's condemnation of educators who seek to implant "inert ideas" (1929, p. 15) into their students. Such an enterprise was, in their shared view, not just pointless, but even harmful. However, once one moves beyond this shared condemnation of "verbalism," of what teachers should not do, it is difficult to find agreement concerning what teachers should do. A number of these differences are treated below, beginning with their divergent views on the aims of education. The Aims of Education It should, perhaps, not be surprising to find that Piaget, the man who made the creation of new knowledge the focus of genetic epistemology, also made the creation of new knowledge the primary end of education: "The principal goal of education is to create men who are capable of doing new things, not simply repeating what other generations have done--men who are creative, inventive, and discoverers" (Piaget in Elkind, 1989, p. 115). In order to achieve this goal, Piaget contended that "the second goal of education ....[should be] to form minds which can be critical, can verify, and not accept everything that is offered" (Piaget in Elkind, 1989, p. 115). In other words, it is not enough just to think of new ideas. If this was sufficient, then we could all be philosophers. However, since Piaget (1972) holds that philosophy, alone, is not an adequate basis for producing valid knowledge, then it is necessary to test our new ideas against reality. Thus, broadly stated, the aim of education for Piaget is to enable people to invent and verify new knowledge (Forman & Kraker, 1985). Although Vygotsky's educational aims are not as straightforwardly articulated as Piaget's, they are discernable in his major work, Thinking and Speech (1987), where they are found in his theory of intellectual development. As noted earlier, Vygotsky posited the existence of two lines of intellectual development: a lower natural line and a higher cultural line. Since development consisted of moving from the lower to the higher lines, it is clear that realizing such developmental advances constitutes one of his educational aims. "The focal point of development for the school-age child is the emergence of the higher mental functions" (p. 187). Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 16 For Vygotsky, therefore, the school's job is to ensure that children acquire higher mental functions, functions such as reading, mathematics, and grammar. It is important to note, however, that Vygotsky advocated teaching higher functions, not simply as ends in themselves, but as a means of achieving the end of mindful self-regulation. Attainment of higher level functioning allows people, like Marx's engineer, to plan and realize their own goals. This goal, however, can only be achieved by mastering one's natural abilities with the aid of culturally deeded and internally adapted tools and structures. What is not as discernable in the educational writings of Vygotsky--at least, in those writings currently available in English--is to what purpose he sees people putting the abilities they have acquired in school. Whereas Piaget's ultimate goals of invention and verification saturate his educational writings--indeed, the only things that are truly clear about Piaget's writings on education are the goals, as to opposed to the means, of education--such larger goals are not apparent in Vygotsky. Thus, although, they agree that an aim of education is the formation (albeit by different means) of minds, it is not, yet, evident that they agreed on the ultimate purpose of this endeavor. The Teacher-Child Relationship One of the most salient differences between Piaget's and Vygotsky's perspectives on education concerns the relationship between the teacher and the child. Although Piaget did not write much about this issue, his position is evident in the following comments he wrote about the role of the teacher. It is obvious that the teacher as organizer remains indispensable in order to create the situations and construct the initial devices which present useful problems to the child. Secondly, he is needed to provide counter-examples that compel reflection and reconsideration of over-hasty solutions. What is desired is that the teacher cease being a lecturer, satisfied with transmitting ready-made solutions; his role should be that of a mentor stimulating initiative and research" (1973, p. 16). What's implicitly indicated, if not explicitly stated, is that the teacher and student should stand on relatively equal ground with regard to knowledge. Rather than imparting, instructing, and informing, the teacher's job is to arrange environments, ask probing questions, and stimulate reflection while working alongside the student. This means that the teacher must cease acting as the source of knowledge, because that kind of stance does not lead the child to true knowledge, Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 17 but to imitation knowledge--what Piaget called "school varnish" (DeVries, 1990). To form true knowledge, the teacher must lead the child to think her own thoughts, rather than acquiesce to the teachers' thoughts. From a Vygotskian perspective, however, teachers should stand, in terms of knowledge, not on equal, but unequal footing with regard to the student. The teacher does not just arrange environments and ask stimulating questions, as in a Piagetian approach, but he also "explains, informs, corrects, and forces the child himself to explain" (p. 215-6). To understand why Vygotsky advocated a more assertive role for the teacher than Piaget, it is necessary to digress for a moment to explain his most famous construct, the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Vygotsky's notion of the ZPD emerged from his critique of I. Q. tests which he criticized for, among other things, underestimating children's true intellectual abilities by measuring only what the child could do alone, and thereby neglecting to measure what she could do with (adult) assistance. His point was that if a child could perform at an 8-year-old level on her own, but at a 10-year-old level with guidance, then traditional intelligence tests fail to capture that potential ability. He proposed, therefore, that the child has two levels of development at any one time. First, she has a zone of actual development, which represents what she can do alone. But she also has a zone of proximal development, which is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. (1978, p. 86) Having defined Vygotsky's ZPD it is now possible to explain the two principal reasons why a Vygotskian teacher would be more directive than a Piagetian teacher in the classroom. First, by explaining, correcting, and informing, the teacher can identify a child's potential for development. In this sense, the ZPD is used, not to inculcate knowledge, but to prognosticate imminent areas of intellectual growth in the child by ascertaining precisely what she can achieve with assistance from others. That is, by assisting the child, the teacher identifies those functions that have not yet matured but are in the process of maturation, functions that will mature tomorrow but are currently in an embryonic state. These functions could be termed the 'buds' or "flowers' of development rather than the 'fruits' of development. (1978, p. 86) Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 18 There is a second sense in which the ZPD is used and that is as a means to ensure that the potential buds of development really do bear fruit. In other words, the teacher does not merely identify possible future growth and then watch it mature, rather he uses "instruction to bring out those processes of development that now lie in the zone of proximal development" (1987, p. 211) that he has already identified. Thus, there's a clear contrast between the Piagetian and Vygotskian perspectives on the nature of the relationship between the teacher and the child. For Piaget, teacher-child relations should be symmetrical, with regards to knowledge, because this arrangement allows the child to advance to higher levels by constructing increasingly valid intellectual structures; and this construction occurs best when the teacher works with, not over, the student. By contrast, for Vygotsky, the teacher-child relationship should be asymmetrical, allowing the child to advance by appropriating, within the ZPD, an increasingly differentiated set of social tools; and this appropriation occurs most readily when the teacher guides, corrects, and directs the child as she participates in valued cultural practices. Education and the Formation of Higher Level Concepts An important question to ask of any educational theory is as follows: How do children learn higher level concepts? Piaget and Vygotsky provide different responses to this question, and their differences stem from the fact that they have conflicting views on the relationship between scientific and spontaneous concepts. In order to understand these differences, though, it is necessary to begin this section by defining these two constructs. Spontaneous concepts are the ideas that children make of the world based on everyday activities. What's important about them is that they are acquired by the child outside of the control of explicit instruction. In themselves these concepts are mostly taken from adults, but they never have been made to connect them with other, related concepts (Van der Veer & Valsiner, 1992, p. 270) On the other hand, scientific concepts are concepts with formal definitions that, usually, "have been explicitly introduced by a teacher at school" (Van der Veer & Valsiner, 1992, p. 270). Such concepts are not necessarily scientific, in the formal sense of the word, though, and are often referred to by contemporary scholars as "schooled" concepts (Tharp & Gallimore, 1990, p. 193). Children generally are familiar with, and have built a spontaneous concept of the term "brother," Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 19 based on their informal experiences; by contrast, their knowledge of schooled concepts, such as Archimedes's law, does not stem from everyday experience, but from formal instruction (Vygotsky, 1987). Piaget and Vygotsky would both have agreed that a legitimate goal of education is for people to master higher level concepts. Where they seriously disagreed, though, was on the wisdom of using schooled concepts to lead young children to this goal. Piaget clearly recognized that societies have always conveyed to the individual an already prepared system of ideas, classifications, relations--in short, an inexhaustible stock of concepts which are reconstructed in each individual after the ageold pattern which previously moulded earlier generations. (1966, p. 159) It is these ideas and relations that have traditionally been seen as the proper content of classroom instruction. For Piaget, however, exposure to such concepts is not truly educative because it does not--indeed, cannot--raise the child's level of intellectual functioning. This is because, when exposed to these higher level thoughts, the child begins by borrowing from this collection only as much as suits him, remaining disdainfully ignorant of everything that exceeds his mental level. And again, that which is borrowed is assimilated in accordance with his intellectual structure; a word intended to carry a general concept at first engenders only a half-individual, half-socialized preconcept. (1966, p. 159) The lesson for educators who seek to instruct children in these ideas is that, when exposed to adult thought, children cannot help but pull it down to their level. However dependent he may be on surrounding intellectual influences, the young child assimilates them in his own way. He reduces them to his own point of view and therefore distorts them without realizing it" (1966, p. 160, emphasis added). For Piaget, exposing children to high-level thinking is pointless. The only way for children to acquire schooled concepts is to first construct the intellectual structures that will eventually allow them to be assimilated. It is only after the appropriate structures have been endogenously constructed through spontaneous activity that higher level concepts can be truly understood. Vygotsky agrees with Piaget's contention that children's initial attempts to produce adult concepts will invariably be unsuccessful; that they will not produce accurate schooled concepts, but a developmental sequence of "preconcepts" (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 189). For Vygotsky, Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 20 however, preconcepts do not represent a failure of educational transmission, but the beginning of the educational process; a process in which the child will produce, with the assistance of the teacher, a series of "failed," yet increasingly adequate concepts. This developmental process is not straightforward, though. It involves a dynamic interaction, a dialectic, between the child's spontaneous concepts and society's scientific ones, all of which occurs within the ZPD with the teacher guiding the process. While this process may take place over a long time, the final outcome of this productive clash (between the spontaneous and the systematic) will be a fully developed concept, one that has both the experiential richness of everyday concepts and the systematic advantages of schooled ones. To summarize, Piaget and Vygotsky are alike in conceiving of children's attempts to grasp scientific concepts in formal instructional situations as initially resulting in failure. Their views of this failure differ, though, in much the same way that people view a glass of water as half-full, or half-empty. For Piaget, a preconcept is half-empty; it illustrates the failure of children to grasp ideas beyond their stage of intellectual development. For Vygotsky, however, a preconcept is half-full: it shows that children grasp some part, however limited, of a higher-level concept. And it is this "failed" concept which the teacher and child use to climb to developmentally higher levels. Thus, whereas Piaget "sees only the break, not the connection" (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 174) between schooled and spontaneous concepts, Vygotsky focuses on the connection and advocates using it as a link to the development of higher level concepts. The Curriculum Piaget's approach to the curriculum is evident in the following excerpt where he differentiates subjects according to the way in which truth is ascertained. There are some subjects, such as French history or spelling, whose contents have been developed, or even invented, by adults, and the transmission of which raises no problems other than those related to recognizing the better or worse information techniques. There are other branches of learning, on the other hand, characterized by a mode of truth that does not depend upon more or less particular events resulting from many individual decisions, but upon a process of research and discovery... a mathematical truth is not dependent upon the contingencies of adult society, but upon a rational construction accessible to any healthy intelligence (1971a, p. 26). Thus, he differentiated subjects according to their mode of truth: some subjects are best characterized as social-arbitrary inventions; others as research-based scientific constructions. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 21 For Piaget, arbitrary subjects, such as history, could be taught via cultural transmission. Nonarbitrary subjects, however, such as math, science, and logic, could not be transmitted; they can only be grasped when invented or re-invented by the child herself. Of these two kinds of subjects, those characterized by rationality and research are more highly valued from a Piagetian perspective. This is because these topics lead to the "formation of individuals capable of inventive thought and of helping the society of tomorrow to achieve progress" (1971a, p. 26). And it is these topics which are still the primary focus of much of constructivist education today (Forman, 1993). It is important to remember, though, that these subjects are not valued as ends in themselves, but as a means to the greater end of intellectual freedom and creativity. This view is evident in Piaget's rhapsodizing about the value of mathematics: "There is no field where the full development of the human personality and the mastery of the tools of logic and reason which insure full intellectual independence are more capable of realization [than in mathematics]" (1973, p. 105). In Vygotsky's writings (1978, 1987) a wide variety of school topics (e.g. reading, writing, math, reasoning, science, social science, and drawing) are mentioned. Unlike Piaget, however, he does not privilege topics according to their mode of truth, nor for their potential contribution to an underlying intellectual structure. Instead, these activities are each valued in their own right. This is because these subjects "are given the status of psychological functions rather than being treated as derivatives" (Kozulin, 1990, p. 7). In other words, these skills and functions are valued not solely as a means to a common end of development, as in Piaget; instead, they are valued more as distinct ends in themselves, with each making a unique contribution to overall functioning. This appreciation for the unique contribution of different functions is a reflection of the fact, mentioned earlier, that Vygotsky conceived of intelligence as a domain-specific set of abilities. This idea is succinctly captured in Wertsch's book, Voices of the Mind, (1991) where he describes the mind as a "cultural tool kit." This image invites teachers to think of education less as an effort to form a unitary mental structure, and more as an effort to provide children with a diverse cognitive repertoire of quasi-distinct skills. It is important to ask, though, whether any of the tools identified by Vygotsky are more Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 22 valuable than others. While Vygotsky does not directly address this issue in Thinking and Speech, it seems implicitly clear, given the central role of speech and language in mediating thought, that the primary emphasis in a Vygotskian-based classroom would be placed on literacy. And such an emphasis, based on Vygotksy's writings, is found in Chang-Wells's statement that "it is precisely the development of the ability and disposition to engage in 'literate thinking' through the use of texts that is the school's major responsibility in literate societies" (ChangWells & Wells, 1993, p. 61). It appears, then, that from a Vygotskian perspective, a teacher would be justified in emphasizing the language arts and literacy; whereas, from a Piagetian perspective, a teacher would be justified in emphasizing math and science. Transfer In discussing Piagetian versus Vygotskian views on transfer (i.e., the notion that something learned in one arena can facilitate learning in another arena) it is important to begin by noting Gagné's (1971) distinction between lateral and vertical transfer. In vertical transfer, which Lohman (1993) has characterized as the "general-to-specific dimension of transfer" (Lohman, 1993, p. 21), "a capability to be learned is acquired more rapidly when it has been preceded by preparing learning of subordinate capabilities" (Gagné, 1971, p. 233). By contrast, "lateral transfer occurs when particular knowledge or skills are used to speed up or simplify learning in some other domain" (Brophy & Good, 1986, p. 221). Thus, broadly speaking, lateral transfer occurs between domains, whereas vertical transfer occurs within domains. Historically, debates about transfer have been specifically concerned with lateral transfer, and the argument in favor of this phenomenon was described by Piaget as the hypothesis that an initiation into the dead languages [i.e., Latin or Greek] constitutes an intellectual exercise, the benefits of which may then be transferred to other activities. It is argued, for example, that the possession of a language from which the students' own tongue developed and the ability to manipulate its grammatical structure provides logical tools and develops a subtlety of mind from which the intelligence will benefit later on regardless of the use to which it is put. (1973, Piaget. 61-62) Piaget considered the evidence for transfer and concluded that research had "not yet led to any certain conclusions" (p. 62). His rejection of lateral transfer, though, should not be surprising, because his theory is basically at odds with the concept of transfer across subjects. Since, according to Piaget, logical instruments are not created by language, but by action, one Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 23 could hardly expect him to embrace the idea that learning Latin (or any other language) could produce qualitative advances in a child's intellectual structures. A case for lateral transfer is found, however, in Vygotsky's work. To understand why Vygotsky accepted it, though, it is necessary to point out that when Vygotsky posited the existence of higher functions, he differentiated between two different kinds of higher functions. On the one hand, there is one group "which consists of the processes of mastering the external means of cultural development, e.g. language, writing, counting, drawing" (Vygotsky, 1983, cited in Kozulin, 1990, p. 113, emphasis added). These functions are the specific cultural tools that children learn at school. There are, however, other higher functions, functions which constitute the internal means of cultural development, specifically conscious awareness and mastery, which are common to all of the functions listed above. "The common foundation of all higher mental functions is conscious awareness and mastery. The development of this foundation is the primary formation of the school age" (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 208). In other words, it is the development of the common internal functions (of conscious awareness and mastery) that make possible the eventual appropriation of the external domain-specific higher functions (such as reading, writing, counting, etc.). Thus, for Vygotsky, there is an element of intellectual functioning which can be developed in one domain and transferred to another. In Vygotsky's case, however, what is transferred is not logic or subtlety of mind, but conscious awareness and mastery. In the case of vertical transfer, Vygotsky and Piaget are in alike in that they posit theories of development that include a form of this phenomenon; they differ, though, in the particular form this process takes within their respective theories. The case for vertical transfer in Vygotsky's work begins with his observation that "in each [school] subject, there are essential constituting concepts" (1987, p. 207). For example, dialectic is an essential idea in Marx, and equilibration is an essential idea in Piaget. Once one masters such key concepts, then one has mastered a new framework for understanding the world. When the child masters the structure that is associated with conscious awareness and mastery in one domain of concepts, his efforts will not have to be carried out anew with each of the spontaneous concepts that were formed prior to the development of this structure. Rather, in accordance with basic structural laws, the structure is transferred to the concepts which developed earlier." (p. 217) Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 24 For example, the description provided above of how concepts are restructured within the ZPD constitutes a form of vertical transfer. That is, scientific concepts restructure and, consequently, uplift spontaneous ones by transferring to them a systematic framework. It is important to note, though, that this vertical transfer of structure (in this case from the scientific to the spontaneous level of thought) is possible only because of the lateral transfer of conscious awareness and mastery, functions which underlie the child's ability to grasp any formal structure. (For a more detailed explication/description of the dynamic interplay between spontaneous and scientific concepts, see Glassman [in press].) Although Piaget did not write explicitly about vertical transfer, his theory of stage development does constitute a form of this phenomenon. In contrast with the vertical transfer found in Vygotsky, though, where structure is transferred from the top down (i.e., from the scientific to the spontaneous, from the systematic to the unsystematic) in Piaget's theory structure is transferred from the bottom up (Strauss, 1987). That is to say, in Piaget, knowledge is an expanding spiral (Elkind, 1976) that can only be constructed from the bottom up through the individual's spontaneous organization of experience. To summarize, Vygotsky posits not only the existence of the lateral transfer of conscious awareness and mastery, but he contends that it constitutes one of education's most important contributions to children's intellectual development. For Piaget, however, lateral transfer of logic had not been proved, and it is doubtful that he would have considered the lateral transfer of conscious awareness and mastery to be as important as did Vygotksy, because he insisted that consciousness is constrained by domain-general intellectual structures (Piaget, 1976c, 1976d). By contrast, both would have agreed that spontaneous concepts are involved in a form of vertical transfer, but they would have differed on the direction of this transfer. For Vygotsky, vertical transfer occurs through the top down influence of schooled concepts whose systematic organization gradually enables the restructuring of spontaneous concepts through the active involvement of the child and the instructor. In Piaget, however, vertical transfer occurs only from the bottom up; and it is based, not on the appropriation of preexisting structures acquired through imitation of adult models (as in Vygotsky), but through the invention, via equilibration, of intellectual structures that must necessarily precede any assimilation of higher level concepts. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 25 The Relationship Between Education and Development The remaining difference between Piaget and Vygotsky to be considered in this section concerns the nature of the relationship between education and development. This is a question that Piaget explicitly treated in the 1960's in the following manner: The development of knowledge is a spontaneous process, tied to the whole process of embryogenesis. . . . a process which concerns the totality of the structures of knowledge. Learning presents the opposite case. In general, learning is provoked by situations--provoked . . . [for example] by a teacher, with respect to some didactic point. . . . It is provoked, in general, as opposed to spontaneous. In addition it is a limited process--limited to a single problem, or to a single structure. So I think that development explains learning, and this opinion is contrary to the widely held opinion that development is a sum of discrete learning experiences. . . . In reality, development is the essential process and each element of learning occurs as a function of total development, rather than being an element which explains development. (1966, p. 176, emphasis added) For Piaget, development explains learning because children cannot really learn something unless they have already developed the intellectual structures that allow them to assimilate information presented to them in an instructional situation. As noted earlier, when children are presented with higher level material, they remain "disdainfully ignorant of everything that exceeds [their] mental level. . . . [they] reduce [ideas] to [their] own point of view" (1966, pp. 159-160). This does not mean, as Vygotsky mistakenly implied, that Piaget's child is "impervious" (1987, p. 89) to external (i.e., social) influences; but it does mean that attempts to advance young children's level of intellectual development by exposing them to high-level thinking will not lead to cognitive growth. For Piaget, true cognitive development can only be produced by spontaneous activity. Whereas Piaget's account of cognition subordinated education to development, Vygotsky's account subordinated development to education. For Vygotsky, "the most essential feature of our hypothesis is the notion that developmental processes do not coincide with learning processes. Rather, the developmental process lags behind the learning process" (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 90). Vygotsky takes this position because he views instruction as 1) being a source of, and 2) giving direction to, development: "It is reasonable to anticipate that research will show that instruction is a basic source of the development of the child's concepts and an extremely Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 26 powerful force in directing this process" (1987, p. 177). Instruction is a source of development in that, when a teacher helps a child acquire, for example, a scientific concept, this provides the child with an organized framework, a system through which she may view the world. The child, however, neither automatically nor accurately adopts this framework; instead, she uses teachersupplied (scientific) concepts and terms in her own unique fashion. Consequently, instruction must also provide direction to this process in order to ensure that the developmental sequence produced by the dialectic between the child's spontaneous ideas and society's formal ideas leads to the appropriate endpoint. And the strategies the teacher uses to guide this process include explanation, modelling, and collaboration. It is this use of instruction to initiate and guide development in a particular direction that occurs in the Zone of Proximal Development. Consequently, for Vygotsky, "development based on instruction is a fundamental fact. . . . The only instruction which is useful in childhood is that which moves ahead of development" (1987, pp. 210-211). When considering these opposing views concerning the relationship between education and development, though, it is crucial to remember that each theorist focuses on a different set of objects that develop in ontogenesis: Piaget, focuses on the development of a universal domaingeneral intellectual structure, a structure whose rate, but not direction, of growth is influenced by educational practice; Vygotsky, however, focuses on the development of a set of quasi-distinct, domain-specific functions and skills whose rate and direction of growth can vary. Summary I have considered above Piaget's and Vygotsky's differing positions on the aims of education, (vertical and lateral) transfer, the curriculum, the teacher/child relationship, the teaching of higher level concepts, and the relationship between development and education. Rather than reviewing these differences, though, it will be more useful to complete this section on their differing perspectives on education by highlighting the factors that underlay and explain their differences on these issues: namely, the different mechanisms that lead to (what each considers to be important in) intellectual development, and, consequently, the mechanisms that need to be addressed in the classroom. As mentioned above, the primary mechanism of cognitive advance, for Piaget, is invention, via equilibration, of increasingly valid domain-general structures, structures that are Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 27 universal. This position is clearly reflected both in the title of one of his volumes on education, To understand is to invent (1973), and in his statement that "everything one teaches a child one prevents him from inventing or discovering" (Bringuier, 1980, p. 102a). Accordingly, from this perspective, the teacher's job is, neither to model, nor to explain, but to stimulate and support exploration, invention, and research. For Vygotsky, however, it is not invention, but imitation, that is at the heart of what occurs (or should occur) in classrooms; and, accordingly, it is imitation that should be the principal object of study for educational researchers. A central feature for the psychological study of instruction is the analysis of the child's potential to raise himself to a higher intellectual level of development through collaboration, to move from what he has to what he does not have though imitation. This is the significance of instruction for development. It is also the content of the concept of proximal development. Understood in a broad sense, imitation is the source of instruction's influence on development. (1987, pp. 210-211, emphasis added) It is crucial to note, however, that this does not mean that the child is capable of "automatic copying" (p. 210)--a view, characteristic of empiricist accounts of intellectual development, that is thoroughly rejected by Vygotsky (and by Piaget [1971b]); nor does it mean that the child plays a passive role in acquiring, through imitation, the social tools of higher thought. What it does mean, though, is that Vygotsky saw the child as capable of "meaningful imitation" (p. 210). That is, it is because the child can mindfully appropriate and use for her own purposes higher functions and systems, via socially guided imitation in the zone of proximal development, that imitation can lead to intellectual advance. And it is the reliance on imitation, as opposed to invention, which accounts for the differing educational perspectives that have been reviewed in this section. In noting their reliance on different mechanisms, though, we run, once again, into the difficulty of comparing aspects of theories designed to address different problems (Glick, 1983). Although it is true that Piaget and Vygotsky rely on different mechanisms to account for the transformation of intellectual structures in cognitive development, these mechanisms don't produce the same product. Is it possible, then, given the same educational goal to realize, that their approaches might prove to be similar? The best way to address this question is to consider how they might realize the same goal. Since Vygotsky and Piaget both agree that a legitimate Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 28 goal of education is the formation of mind, I shall, therefore, consider how, from each perspective, instruction might promote the formation of critical thought in children. For Piaget, the way to meet this goal is to facilitate the child's invention of intellectual structures, of a logic that will allow her to think critically. Creation of such structures occurs most readily in classrooms where free flowing discussion is encouraged both between instructors and students, but especially between peers. "Criticism is born of discussion, and discussion is only possible among equals." (Piaget, 1965 in Tudge & Winterhoff, 1993, p. 69). From a Vygotskian perspective, promoting a critical attitude also starts with having a classroom where there is much criticism and discussion. In his case, though, a critical stance is not invented; instead, it is acquired from the models and structures present in the classroom. This is evident in Brown and Campione's explication of the ZPD as a process where "the supportive other acts as the model, critic, and interrogator, leading the child to use more powerful strategies and to apply them more widely. In time, the interrogative, critical role is adopted by the child, who becomes able to fulfill some of these functions for herself via selfregulation and self-interrogation" (1984, p. 145). Accordingly, from his perspective, there is a more formative role for the teacher to play, and, correspondingly, less faith that unguided peer interaction will lead to the desired endpoint. In brief, then, given the aim of the formation of critical thought, Piaget and Vygotsky would use related, yet distinct, strategies to achieve this end. They would concur that, to promote critical thinking, criticism and discussion should permeate the classroom. Yet, they tell a different story of how such an atmosphere influences the child. For Piaget, the teacher fosters a critical environment in order to enable the child "to construct for [her]self the [domain-general] tools that will transform [her] from the inside" (104, p. 121, emphasis added). For Vygotsky, however, the teacher fosters a critical environment in order to enable the child to appropriate from the outside the tools that, once internalized, will then transform her from the inside. And, it is because they have different accounts of the origin of the structures that transform the child's mind, that they have different conceptions of the teacher/child relationship, the curriculum, the teaching of higher level concepts, transfer, and, ultimately, the relationship between education and development. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 29 Conclusion Although the points covered in this paper do not constitute an exhaustive exposition of the differences which separate Piaget and Vygotsky, they clearly show that their differences are substantial and substantive. They disagree on a number of issues which are fundamental to any account of intellectual development: namely, the nature of human intelligence, the role of mediational tools (especially language), the mechanisms of change in development, and the influence of social factors. They also differ on a number of fundamental educational issues: namely the aims of education, the teacher-child relationship, the curriculum, transfer, and the relationship between education and development. These contrasts stem, in large part, from the distinctly different problems they sought to investigate in their work. Before returning to the question posed at her beginning of the paper, i.e. whether their answers to their respective problems may be integrated, I shall first consider a problem common to both approaches when applied to education. Piaget and Vygotsky are similar in that they both produced theories that present challenges to anyone attempting to apply them to the classroom. To begin with, Piaget did not make many explicit recommendations for educators; and the few recommendations he did make were of a general nature (DeVries & Kohlberg, 1988). This absence of educational prescriptions stems from the fact that he viewed himself "as a biologically oriented epistemologist first, a psychologist second, and an educator not at all" (Elkind & Flavell, 1969, p. xviii). Since his research focused on the development of knowledge in general, he had a limited foundation on which to base any educational recommendations. "Educational applications of Piaget's experimental procedures and theoretical principles will have to be very indirect--and he himself has given hardly any indication of how one would go about it" (Sinclair, 1971, cited in DeVries & Kohlberg, 1988, p. 40) Although education was peripheral to Piaget's interests, it was central to Vygotsky's. He contended that school is where children acquire so many of the uniquely human functions, sign systems, and concepts that characterize higher intellectual functioning. This is why Bruner has characterized Vygotsky's theory as, among other things, "a theory of education" (1987, p. 1). Nevertheless, despite the centrality of education to Vygotsky's writings, there are serious Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 30 problems with his work, problems which stem primarily from his imprecision (Elkonin, 1966). Unfortunately, many of the core constructs of his theory were inadequately articulated. Wertsch and Tulviste (1992), for example, have noted how culture, a key part of his theory (Kozulin, 1991), is poorly rendered. More importantly for the current discussion, though, even his most famous educational construct, the Zone of Proximal Development, was also poorly defined (Wertsch, 1984). What is ironic about this state of affairs is that these theories which are among the strongest influences on contemporary conceptions of young children's intellectual development, and, consequently, on contemporary educational psychology, are both limited with regards to their specific implications for education. On the one hand, Piaget's work is limited because of its specific range of application. The research he pursued only permits comments of a general nature to be made about the educational process. On the other hand, Vygotsky's work is limited because of its imprecision. Although his theory does allow--indeed calls out for--educational recommendations, those that he made himself are sketchy and need to be fleshed out. Consequently, Vygotsky and Piaget are alike in that they both left much work for their educational followers to refine and extend. Nevertheless, even if the followers of Vygotsky and Piaget succeed in articulating expanded and coherent educational applications of these two approaches, they will be hard pressed to overcome the larger limitations that are inherent in the respective problems which these two researchers initially sought to address, limitations that restrict their implications both for education and for intellectual development. As noted earlier, Piaget set out to explain the creation of new knowledge, and Vygotsky set out to explain the transmission (and acquisition) of uniquely human forms of knowledge. The difficulty with building a theory on the answers to either one of these particular problems, though, is that neither set of answers is likely to provide a complete account of either intellectual development (Glick, 1983) or of education. Piaget provides a theory of individual invention, but not of cultural transmission. Vygotsky provides an account of cultural transmission, but not of individual invention. Yet, if we want, as Dewey did, to have a theory "provide for both cultural renewal and cultural transmission" (Archambault, 1974, p. xxvii), then we need an approach that can explain invention and transmission. Since, as Goodnow has noted, this need is apparently shared by most researchers and Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 31 theorists--"no one finds it satisfactory to attribute development to either 'discovery' or 'transmission'" (1993, p. 376)--the question returns to how may we use the important insights of both Piaget and Vygotsky to build a richer and more complete account of both development and education. That is, we return to the question of the extent to which their theories may be integrated. A number of affirmative responses to this question are considered below. The most ambitious approach is that of Feldman (1980, 1988) who has proposed a theory that includes developmental sequences that range from the universal to the unique. This approach honors both the Vygotskian and the Piagetian perspectives by 1) acknowledging the universal and the non-universal aspects of intellectual development and 2) attempting to explain the relationship between invention and transmission along a spectrum of developmental sequences. (Tulviste [1991] has proposed an approach that is similar to Feldman's inasmuch as he advocates the study of activities that are both universal and culturally specific; it is dissimilar, though, in that he eschews the Piagetian perspective and tackles these questions exclusively from a Vygotskian viewpoint.) Consonant with Feldman's approach are attempts to integrate Vygotskian and Piagetian insights, not within a larger theory, but within a particular developmental sequence or domain. Strauss, for example, who has relatedly advocated the establishment of a "middle-level of educational-developmental psychology that allows investigators to have their work informed by developmental psychology and, at the same time, to have their research impact upon education theory and practice" (1987, p. 133), has pursued this strategy in science education (Strauss, 1987, 1991), as have others in both mathematics (Saxe, 1991), and play (Nicolopoulou, 1993). In addition, Case has argued that a number of explicitly neo-Piagetian theorists, e.g., Case (1992a), Fischer (1980), and Pascual-Leone (1988), have produced accounts that could "ultimately become more congruent with, and perhaps even make some contribution to, sociohistoric theory" (1992b, p. 95). (It should be noted, though, that Karmiloff-Smith has vigorously argued that many "neo-Piagetian" accounts are not Piagetian, that they "retain none of the core features of Piaget's theory" [1993, p. 3].) Finally, there are also researchers who approach the integration problem, less from an integrative, and more from an eclectic perspective: specifically, they have appreciated the distinct contributions of Piaget and Vygotsky, but without explicitly placing these contributions Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 32 within a single theory. These writers (Damon, 1984; Damon & Phelps, 1989: Forman & Kraker, 1985; Tudge & Rogoff, 1989; Tudge & Winterhoff, 1993) have all pointed out the valuable contributions that Piaget and Vygotsky have made to our understanding of both development and education, but they do not attempt to fully integrate these perspectives. An alternate approach to the question at hand, of course, is not to attempt any integration at all. This strategy is advocated by a number of writers who have largely dismissed the possibility of a substantive synthesis of Piaget's and Vygotsky's theories (Bakhurst, Cole, Middleton & Nicolopoulou, 1988; DeVries & Zan, 1992; Downs & Liben, 1993; Forman, 1993; Wertsch, 1985; Wozniak, 1987). Rather than reviewing each of their arguments, though, I shall outline below the two principal issues that should prove to be the most challenging to reconcile. First, there is the question of the relationship between universal and non-universal sequences of development (Downs & Liben, 1993). Although Vygotsky and Piaget would both have agreed that there are universal and non-universal sequences of development, they would not have agreed on the relative importance of these sequences. For Piaget, it is the development of a universal (domain-general) tool of intelligence that both enables and constrains the development of non-universal (domain-specific) tools of intelligence. For Vygotsky, however, the products of universal development, alone, should not be given primary credit for realization of the highest forms of human thought. For him, it is the products of non-universal development (i.e., culturally specific systems and structures) that allow thought to achieve its highest levels. In particular, though, it is because, according to Vygotsky, thought can be mediated, and, ultimately, elevated through (culturally developed) techniques, that non-universal development is important. Therefore, it is the issue of mediation which constitutes the second major point of contention between these two thinkers (Wozniak, 1986). Piaget does not credit mediation with the capacity to qualitatively influence thought, whereas Vygotsky does; and this issue is intimately related to their differing emphases on the development of universal versus nonuniversal structures. The extent to which Piaget and Vygotsky may, or may not, be integrated will depend largely on the extent to which these two overlapping issues may be reconciled. This is a matter for debate. Although it is not presently clear how these questions will be resolved, it is clear that both developmental and educational psychology need a theory that can deal with universal and Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 33 non-universal development, with transmission and invention. To develop such a theory, however, we need to understand that Piaget and Vygotsky have valuable insights to offer each other. Accordingly, informed debate between the two camps should promote the development, if not of the integration, of enriched and broadened extensions of these two monumentally important perspectives. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 34 References Archambault, R. D. (1974). Introduction. In R. D. Archambault (Ed.), John Dewey on education: Selected writings (pp. xiii-xxx). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bakhurst, D., Cole, M., Middleton, D., & Nicolopoulou, A. (1988). Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky. Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 10 (4), 98-99. Bearison, D. J. (1991). Interactional contexts of cognitive development: Piagetian approaches to sociogenesis. In L. T. Landsmann (Ed.), Culture, schooling and psychological development (pp. 56-70). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Bidell, T. (1988). Vygotsky, Piaget and the dialectic of development. Human Development, 31, 329-348. Bidell, T. (1992). Beyond interactionism in contextualist models of development. Human Development, 35, 306-315. Bringuier, J.-C., (1989). Conversations with Jean Piaget. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1980) Brophy, T. L., & Good, J. E. (1986). Educational psychology (3rd ed.). New York: Longman. Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1984). Three faces of transfer: Implications for early competence, individual differences, and instruction. In M. E. Lamb, A. L. Brown, & B. Rogoff (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 143-192). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 35 Brown, T. (1988). Why Vygotsky? The role of social interaction in constructing knowledge. The Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 18 (4), 111117. Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bruner, J. (1987). Prologue to the English edition. In R. Rieber & A. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 1, pp. 1-16). New York: Plenum. Case, R. (1992a). The mind's staircase: Exploring the conceptual underpinnings of children's thought and knowledge. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Case, R. (1992b). Neo-Piagetian theories of intellectual development. In H. Beilin & P. Pufall (Eds.), Piaget's theory: Prospects and possibilities (pp. 61-104). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Chang-Wells, G. L. M., & Wells, G. (1993). Dynamics of discourse: Literacy and the construction of knowledge. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick, & C. A. Stone (Eds.) Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development (pp. 58-90). New York: Oxford University Press. Chapman, M. (1988). Constructive evolution: Origins and development of Piaget's thought. New York: Cambridge University Press. Cole, M. (1990). Cognitive development and formal schooling: The evidence from crosscultural research. In L. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology (pp. 89-110). New York: Cambridge University Press. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 36 Damon, W. (1984). Peer education: The untapped potential. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 5, 331-43. Damon, W., & Phelps, E. (1989). Critical distinctions among three approaches to peer education. International Journal of Educational Research, 13, 9-19. DeVries, R. (1990, November). The aim of constructivist education: Intellectual, social and moral development. Paper presented at Lesley College's Expanded New England Kindergarten Conference, Randolph, MA DeVries, R., & Kohlberg, L. (1988). Programs of education: The constructivist view. New York: Longman. Devries, R. & Zan, B. (1992, May). Social processes in development: A constructivist view of Piaget, Vygotsky and education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Jean Piaget Society, Montreal, Quebec. Downs, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (1993). Mediating the environment: Communicating, appropriating, and developing graphic representations of place. In R. H. Wozniak & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific contexts (pp. 155181). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Elkind, D. (1976). Child development and education: A Piagetian perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. Elkind, D. (1989). Developmentally appropriate practice: Philosophical and practical applications. Phi Delta Kappan, October, 113-117. Elkind, D., & Flavell, J. H. (Eds.). (1969). Studies in cognitive development: Essays in honor of Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 37 Jean Piaget. New York: Oxford University Press. Elkonin, D. B. (1966). The problem of instruction and development in the works of L. S. Vygotsky. Soviet Psychology, 12 (6), 33-41. Feldman, D. H. (1980). Beyond universals in cognitive development. Norwood: Ablex. Feldman, D. H. (1988). Universal to unique: Toward a cultural genetic epistemology. Archives de Psychologie, 56, 271-279. Fischer, K. W. (1980). A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review, 87, 477-531. Forman, E. A., & Kraker, M. J. (1985). The social origin of logic: The contributions of Piaget and Vygotsky. In M. W. Berkowitz (Ed.), Peer conflict and psychological growth (pp. 2339). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Forman, E. A., Minick, N., & Stone, C. A. (Eds.). (1993). Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development. New York: Oxford University Press. Forman, G. (1993). The constructivist perspective to early education. In J. L. Roopnarine & J. E. Johnson (Eds.), Approaches to early childhood education (2nd ed., pp. 137-155). New York: MacMillan. Gagné, R. M. (1965). The conditions of learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic. Glassman, M. (in press). All things being equal: The two roads of Piaget and Vygotsky. Developmental Review. Glick, J. (1983). Piaget, Vygotsky, and Werner. In S. Wapner & B. Kaplan (Eds.), Toward a Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 38 holistic developmental psychology (pp. 35-52). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Goodnow, J. J. (1993). Direction of post-Vygotskian research. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick, & C. A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development (pp. 369-381). New York: Oxford University Press. Hatano, G. (1993). Time to merge Vygotskian and constructivist conceptions of knowledge acquisition. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick, & C. A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development (pp. 153-166). New York: Oxford University Press. Inhelder, B. (1992). Foreword. In H. Beilin & P. Pufall (Eds.), Piaget's theory: Prospects and possibilities (pp. xi-xiv). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1993, Spring). Neo-Piagetians: A theoretical misnomer? SRCD Newsletter, pp. 3,10-11. Kozulin, A. (1990). Vygotsky's psychology: A biography of ideas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lee, B. (1985). Intellectual origins of Vygotsky's semiotic analysis. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), Culture and communication: Vygotskian perspectives (pp. 66-93). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lohman, D. F. (1993). Teaching and testing to develop fluid abilities. Educational Researcher, 22 (7), 12-23. Minick, N., Stone, C. A., & Forman, E. A. (1993). Integration of individual, social, and Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 39 institutional processes in accounts of children's learning and development. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick, & C. A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development (pp. 3-16). New York: Oxford University Press. Nicolopoulou, A. (1993). Play, cognitive development, and the social world: Piaget, Vygotsky, and beyond. Human Development, 36, 1-23. Pascual-Leone, J. (1988). Organismic processes for neo-Piagetian theories: A dialectical causal account of cognitive development. In A. Demetriou (Ed.), The neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development: Toward an integration. Amsterdam: North Holland. Piaget, J. (1964). Development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2, 176186. Piaget, J. (1965). The moral judgment of the child. New York: Free Press. (Original work published 1932) Piaget, J. (1966). The psychology of intelligence. Totowa, NJ: Littlefield, Adams & Co. (Original work published 1947) Piaget, J. (1967). The significance of John Amos Comenius at the present time. In John Amos Comenius on education (pp. 1-31). New York: Teachers College Press. Piaget, J. (1971a). Science of education and the psychology of education. New York: Viking Press. (Original works published in 1935 and 1965) Piaget, J. (1971b). Genetic epistemology. New York: Norton. Piaget, J. (1972). Insights and illusions of philosophy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1965) Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 40 Piaget, J. (1973). To understand is to invent: The future of education. New York: Viking Press. (Original work published 1948) Piaget, J. (1976a). The necessity and significance of comparative research in genetic psychology. In The child and reality (pp. 143-162). New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1966) Piaget, J. (1976b). Language and intellectual operations. In The child and reality (pp. 109-124). New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1954) Piaget, J. (1976c). Affective unconscious and cognitive unconscious. In The child and reality (pp. 31-48). New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1971) Piaget, J. (1976d). The grasp of consciousness: Action and concept in the young child. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1974) Piaget, J. (1977). Etudes sociologiques (3rd. ed.). Geneva: Librarie Droz. (Original work published 1965) Piaget, J. (1980a). Adaptation and intelligence: Organic selection and phenocopy. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. (Original work published 1974) Piaget, J. (1980b). Schemes of action and language learning. In M. Piattelli-Palmarini (Ed.), Language and learning: The debate between Jean Piaget and Noam Chomsky, (pp. 164-167). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Piaget, J. (in press). Sociological studies. New York: Routledge Rogoff, B. (1988). Commentary. Human Development, 31, 346-348. Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in context. New York: Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 41 Oxford University Press. Saxe, G. (1991). Culture and cognitive development: Studies in mathematical understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Sinclair, H. (1971). Piaget's theory of development: The main stages. In M. Rosskopf, L. Steffe, & S. Taback (Eds.), Piagetian cognitive-development research and mathematical education. Washington, D. C.: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Strauss, S. (1987). Educational-developmental psychology and school learning. In L. Liben (Ed.), Development and learning: Conflict or congruence? (pp. 133-157). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Strauss, S. (1991). Towards a developmental model of instruction. In S. Strauss (Ed.), Culture, schooling, and psychological development (pp. 112-135). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Tharp, R., & Gallimore, R. (1990). Teaching mind in society: Teaching, schooling, and literate discourse. In L. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology (pp. 175-205). New York: Cambridge University Press. Tudge, J. R. H., & Rogoff, B. (1989). Peer influences on cognitive development: Piagetian and Vygotskian perspectives. In M. Bornstein & J. Bruner (Eds.), Interaction in human development (pp. 17-40). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Tudge, J. R. H., & Winterhoff, P. A. (1993). Vygotsky, Piaget, and Bandura: Perspectives on the relations between the social world and cognitive development. Human Development, 36, 61-81. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 42 Tulviste, P. (1991). The cultural-historical development of verbal thinking. Commack, NJ: Nova Science Publishers Van der Veer, R. , & Valsiner, J. (1990). Understanding Vygotsky: A quest for synthesis. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 147-188). Armonk, NY: Sharpe. Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. Rieber & A. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (pp. 37-285). New York: Plenum. Wartofsky, M. (1971). From praxis to logos: Genetic epistemology and physics. In T. Mischel (Ed.), Cognitive development and epistemology (pp. 129-147). New York: Academic Press. Wartofsky, M. W. (1983). From genetic epistemology to historical epistemology: Kant, Marx, and Piaget. In L. Liben (Ed.), Piaget and the foundations of knowledge (pp. 1-17). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Wertsch, J. V. (1981). Editor's introduction. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 144-147). Armonk, NY: Sharpe. Wertsch, J. V. (1984). The zone of proximal development: Some conceptual issues. In B. Rogoff & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), New Directions for Child Development. Vol. 23: Children's learning in the "Zone of Proximal Development", (pp. 7-18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Piagetian Versus Vygotskian 43 Wertsch, J. (1990). The voice of rationality in a sociocultural approach to mind. In L. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology (pp. 111-126). New York: Cambridge University Press. Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Wertsch, J. V., & Tulviste, P. (1992). L. S. Vygotsky and contemporary developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 28, 548-557. Whitehead, A. N. (1929). The aims of education and other essays. New York: MacMillan. Wozniak, R. (1987). Developmental method, zones of development, and theories of development. In L. Liben (Ed.), Development and learning: Conflict or congruence?, (pp. 225-235). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Zimmerman, B. J. (1993). Commentary. Human Development, 36, 82-86. View publication stats