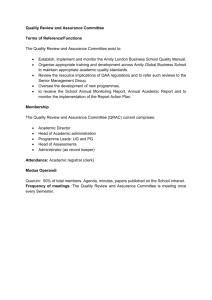

The Case of Sustainability Assurance: Constructing a New Assurance Service* BRENDAN O’DWYER, University of Amsterdam Business School 1. Introduction The economic success of the Big Four professional accounting firms has been influenced by their willingness and ability to expand into new and potentially lucrative areas of business from a traditional base in auditing, taxation, and insolvency (Power 1997; Gendron and Barrett 2004; Free, Salterio, and Shearer 2009). In the past two decades many of these firms have translated their core expertise in financial audit to successfully develop and secure new markets in areas such as e-commerce assurance (Gendron and Barrett 2004) and environmental auditing (Power 1997, 2003). This expansion has been partly facilitated by the ability of accountants to translate the concepts and terminology underpinning traditional attest audits into nonfinancial audit arenas (Power 1997, 1999; Free et al. 2009). A recent manifestation of this translation is evident in the Big Four professional services firms’ capture of a significant share of the growing market in assurance on sustainability reports (termed sustainability assurance).1 This market is shared among certification bodies, specialist consultancies, and the Big Four professional services firms. KPMG’s (2008) recent worldwide survey revealed that the Big Four firms control 70 percent of the sustainability assurance market among G250 companies.2 Given this growth and the accompanying increased involvement of professional accountants in its delivery, * Accepted by Yves Gendron. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2010 Contemporary Accounting Research Conference, generously supported by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants. This paper has benefited from the helpful comments of Shannon Anderson, Roel Boomsma, Mary Canning, Wai Fong Chua, Jesse Dillard, Mahmoud Ezzamel, Clinton Free, Yves Gendron, Georgios Georgakopoulos, Mike Gibbins, James Hazelton, Reggy Hooghiemstra, Chris Humphrey, Thomas Riise Johansen, Nonna Martinov-Bennie, Hugh McBride, John Roberts, Vaughan Radcliffe, Steve Salterio, and Marc Wouters. Highly helpful comments were also received from two anonymous reviewers, a reviewer for the 6th Asia-Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting (APIRA) Conference at the University of Sydney, and participants at: the 12th Alternative Accounts Conference and Workshop, Schulich School of Business, Toronto; the University of Sydney Discipline of Accounting research seminar series; the 6th Asia-Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting (APIRA) Conference at the University of Sydney; the 10th Seminar of the Research Centre of Accounting and Control Change (RACC) at the Open University, Eindhoven; the 25th anniversary Contemporary Accounting Research conference hosted by Queen’s University in Kingston; and the Royal Holloway, University of London, Accounting, Finance and Economics research seminar series. The author would also like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the interviewees who participated in the study. 1. Sustainability reports refer to stand-alone reports in which companies disclose information on their economic, environmental, and social activities and impacts. Reporting formats tend to vary, but an increasing number of companies around the world now comply with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 2008 G3 reporting guidelines. These include categorizations comprising economic, environmental, and social performance (labor practices and decent work, human rights, society, and product responsibility) indicators. 2. Big Four firms had 58 percent of the market in KPMG’s 2005 study (KPMG 2008). The G250 sample comprises the top 250 of the Fortune 500 companies. Seventy-nine percent of all G250 companies published stand-alone sustainability reports in 2008. Forty percent of these reports included formal assurance statements (compared with 30 percent in 2005) (KPMG 2008). Simnett, Vanstraelen, and Chua (2009) analyzed 2,113 sustainability reports (from 31 countries) for 2002–2004 and found that 31 percent of the reports contained assurance statements, with almost 42 percent of them being prepared by Big Four firms. This level of assurance practice contrasts with the limited evidence of practice in the late 1990s (Nitkin and Brooks 1998; Ball, Owen, and Gray 2000). Contemporary Accounting Research Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) pp. 1230–1266 CAAA doi:10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01108.x The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1231 sustainability assurance has made its way onto the agendas of several international and national professional accounting standard-setting bodies. These include the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), which indicated its intention to develop a sustainability assurance standard in its strategic aims for 2009 to 2011 (IAASB 2007).3 This paper has two core objectives. First, it aims to develop our understanding of how assurance practitioners have attempted to construct the practice of sustainability assurance. Second, it seeks to understand how, and the extent to which, these efforts have rendered sustainability reporting auditable. These aims are addressed through a longitudinal case study conducted in two Big Four professional services firms. Drawing primarily on data from 36 in-depth interviews with practitioners and diverse documentary sources, the study specifically investigates the nature of and dynamics surrounding practitioners’ efforts to operationalize sustainability assurance within these organizational contexts. The case analysis is framed using aspects of Power’s 1996, 1997, 1999, and 2003 theoretical insights regarding the processes through which new domains are made auditable. The study’s aims are timely, as increasing attention at both the societal and political level is being paid to corporate social and environmental activities and impacts (Hopwood 2009). Events such as the BP oil spill off the U.S. coastline in 2010 and its social and environmental impacts have served to heighten this scrutiny. The recent establishment of the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC) to create a globally agreed-upon framework for accounting for sustainability has also emerged at a time when sustainability reporting is increasingly subject to critical scrutiny given widespread claims that it is failing to increase the visibility of corporate social and environmental impacts (Hopwood 2009; Gray 2010).4 Sustainability assurance practice promises to provide assurance regarding the reliability and completeness of this reporting. Acquiring an understanding of the processes through which practitioners have approached the construction of assurance practice and the extent to which these efforts may serve to provide assurance on the information in sustainability reports can provide insights into the degree to which emerging assurance practice can inform report users’ assessments of the reliability and credibility they may place on sustainability (and future integrated) reporting content. Most prior academic studies examining sustainability assurance have examined the content of assurance statements (e.g., O’Dwyer and Owen 2005, 2007; Cooper and Owen 2007; Mock, Strohm, and Swartz 2007; Darnall, Seol, and Sarkis 2009; Simnett et al. 2009; Kolk and Perego 2010), while recent experimental work has studied how assurance affects users’ perceptions of the reliability of sustainability reports (Hodge, Subramaniam, and Stewart 2009). The limited research engaging directly with practitioners has largely focused on enhancing our understanding of the processes through which assurance 3. 4. Other professional accounting bodies such as the Federation of European Accountants (FEE 2002, 2004, 2006) and the Dutch Royal NIVRA (Royal NIVRA 2005, 2007) have already issued guidance for professional accountant assurors conducting sustainability assurance-type engagements. The UK professional institute AccountAbility (1999, 2003, 2008) has also developed an assurance standard (AA1000AS) complementing aspects of the guidance emanating from the IAASB’s ISAE 3000 standard (ISAE 2004) on assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information. Additional support and suggestions for sustainability assurance have emanated from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI 2006, 2008) and professional accounting bodies in Germany, Sweden, Australia and Japan (FEE 2006). The IIRC includes the president of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), the chairmen of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), and the chairpersons and chief executives of several major professional services firms and national accounting bodies. The committee aims to present proposals for an Integrated Reporting Framework at the G20 meeting in November 2011. For more details on the IIRC and its aims and activities, please refer to http: ⁄ ⁄ www.integratedreporting.org. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1232 Contemporary Accounting Research statements are formulated as part of efforts to legitimize assurance practice with key audiences (O’Dwyer, Owen, and Unerman 2011).5 Further work has examined practitioner perspectives on the extent to which sustainability assurance is ‘‘adding value’’ for stakeholder groups (Edgely, Jones, and Solomon 2010; see also Wallage 2000).6 This study is distinct from prior field based work due to its longitudinal empirical focus on the processes through which methodological developments have emerged in professional services firm contexts and its theoretical framing, which calls attention to how these processes are rendering sustainability reporting auditable.7 This attention to auditability — the ability to audit — and in particular the processes through which auditability is negotiated and determined prioritizes an examination of a number of issues that are central to obtaining a deeper understanding of how sustainability assurance practice is being constructed. These include: the nature of the interactions between auditors, auditees and existing audit (or assurance) knowledge (Power 1995); the perceived boundaries of audit (or assurance) knowledge in sustainability reporting; and the role and credibility of external specialists who might fill any expertise deficit in sustainability assurance (Power 1999). The paper aims to contribute to the literature by extending and developing prior research investigating auditing and assurance in their social and organizational contexts (e.g., Radcliffe 1999; Cohen, Krishnamoorthy, and Wright 2002; Gendron and Barrett 2004; Barrett, Cooper, and Jamal 2005; Curtis and Turley 2007; Free et al. 2009; Gendron and Spira 2009; Cohen, Krishnamoorthy, and Wright 2010; Gendron and Spira 2010; Trompeter and Wright 2010). First, it responds to continuing calls for researchers to extend examinations of the complex back stage of new ‘‘audit’’-type practices, particularly those of a discretionary nature (Humphrey 2008; Free et al. 2009), in order to develop our limited knowledge and understanding of how audit-associated practices have been exported into new areas and their effects and consequences (Power 2003; Radcliffe 2010). The rare prior work directly examining attempts to extend audit and assurance to new areas has largely focused on public sector environments (Radcliffe 1999; Gendron, Cooper, and Townley 2007; Skaerbaek 2009; but see Free et al. 2009 for an exception); however, the discretionary nature of the sustainability assurance environment within which this study is conducted represents a unique opportunity to examine the construction of a new assurance practice with scope for practical innovation within professional services firm contexts. In this vein, the paper specifically builds on prior work by Radcliffe 1999, examining the operationalization of efficiency auditing, and the work of Free et al. 2009 studying KPMG’s efforts to provide assurance on the Financial Times MBA rankings. The paper’s focus is especially attentive to Radcliffe’s 1999 suggestion that researchers studying the problems professionals encounter, when seeking to conduct their work, should combine a concern with systematic patterns of effects and intentions with the day-to-day calculations, confusions, actions, and inactions which are part of practitioners’ organizational lives. 5. 6. 7. Fourteen of the 36 interviews conducted for this study form a key part of the data used in O’Dwyer et al. 2011. However, the analytical and theoretical focus of O’Dwyer et al. 2011 is distinct from this paper. O’Dwyer et al.’s study focuses on the types of legitimacy and the associated legitimation strategies adopted by practitioners — especially as they are related to the construction of assurance statement content — as part of their efforts to legitimize sustainability assurance with clients, external stakeholders, and internal constituencies within one Big Four professional services firm. Wallage’s 2000 study reflects on some of the issues encountered by KPMG when they conducted sustainability assurance on The Shell [Sustainability] Report in 2000. The paper is a reflective piece written by an individual practitioner ⁄ academic based on his own experiences as opposed to a longitudinal, theoretically informed empirical study independently interpreting a variety of practitioner perspectives on their work in assurance. The terms ‘‘practitioner’’ and ‘‘assuror’’ will be used interchangeably throughout the remainder of the paper. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1233 Second, while much prior work examining the expansion of accounting into new assurance domains has focused on wider institutional level discourses and dynamics (e.g., Swift, Humphrey, and Gore 2000; Gendron and Barrett 2004; Shafer and Gendron 2005; Smith, Haniffa, and Fairbrass 2011), the organizational level focus of this paper seeks to uncover what it is that makes the practice of assurance feasible (or not) for multidisciplinary practitioners operating in professional services firm environments.8 The paper’s prioritization of practitioners’ detailed understandings and practices and the ideals they espouse facilitates an enhanced understanding (Radcliffe 1999; Pentland 2000), as technical practice cannot be disentangled from the stories which are told of its operational capability and possibility (Power 1999). This focus also enables an examination of the processes through which new multidisciplinary practices are evolving in multinational professional services firms. In particular, it reveals how approaches to practice, particularly as related to the gathering and assessment of evidence, are being shaped by practitioners’ diverse backgrounds and training. Third, in addressing its overall aims, the paper considers the interrelationship between the objectives assigned to sustainability assurance and stories of their core operational capability. This focus is rare in prior research (Power 2000; Free et al. 2009), but it is important as it allows us to trace the processes through which the aims held out for new forms of assurance are translated into operational tasks and routines within real-life organizations (Cooper and Robson 2006) and what the effects and consequences of this translation process might be. Overall, the paper’s focus empirically informs Power’s theoretical insights on the export of the idea of ‘‘audit’’ into domains outside its traditional roots in financial audit (1996, 1997, 1999, 2003). The findings reveal the fragile nature of efforts to innovate with assurance and render sustainability reporting auditable. In particular, they expose some of the complexities involved in transferring traditional audit techniques and mindsets to new assurance areas (e.g., Power 1997; Gendron et al. 2007). Practitioners’ tacit knowledge and ‘‘gut feel’’ are initially central to making assurance possible in the presence of vague guidance from global assurance standards. However, tensions between ‘‘accountant’’ (trained financial auditors) and ‘‘non-accountant’’ practitioners (practitioners not trained in financial audit) over legitimate approaches to the gathering and assessment of evidence pervade parts of the practice construction process. In light of the operational challenges encountered, both firms have publicly acknowledged the limitations of traditional financial audit practice for assessing the completeness of sustainability reporting. In order to render sustainability reporting auditable they have simultaneously suggested an external ‘‘expert’’ stakeholder solution that can be coupled with existing financial audit practice. This proposes that company-selected stakeholders should provide separate assurance (and advice) on the completeness and relevance of sustainability report content, with the firms largely limiting their focus to assessing the reliability of the reported data. Overall, the analysis indicates that innovation in new assurance practices (and the auditability of new forms of information) may be restrained by an extensive dependence on financial audit training and techniques and by certain constraints imposed by professional services firm control procedures. 8. The paper’s analysis and research questions focus on developments in sustainability assurance at the professional firm level. Hence, the paper does not deal in depth with developments at the professional body level. While professional body level developments inevitably influence the emergence and ultimate market for practice within professional services firms, for reasons of research focus these broader level debates are used to contextualize the analysis of professional firm developments but do not form the analytical core of the paper (e.g., Radcliffe, Cooper, and Robson 1994; Gendron and Barrett 2004; Fogarty, Radcliffe, and Campbell 2006). CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1234 Contemporary Accounting Research The remainder of the paper comprises six sections. Section 2 uses aspects of Power’s conceptualization (1996, 1997, 1999, 2003) of the processes through which new areas are made auditable to provide theoretical underpinnings for the subsequent case analysis. Section 3 outlines the objectives assigned to sustainability assurance which have emerged from a variety of official sources over the past decade. The data collection and analysis procedures are detailed in section 4. Section 5 describes the two professional services firm contexts studied and section 6 presents the case analysis. Finally, section 7 discusses the case analysis in light of Power’s, 1996, 1997, 1999, and 2003 theoretical insights, presents the main conclusions, and suggests directions for future research. 2. Making new subject areas auditable: The simultaneous construction of stable knowledge and auditable environments Power (1996, 1999) maintains that practitioners make new subject areas auditable (i.e., make it possible to ‘‘audit’’ new areas) by simultaneously creating a consensus around a stable and legitimate knowledge base for audit practice and an auditable environment to which this knowledge can be applied. This co-production of stable knowledge and auditable environments represents a form of ‘‘fact building’’ in which emerging audit technologies — the various formal and informal tasks and routines invoked by practitioners — come to eventually be regarded as common sense, and the newly created audit environments are seen as logically separate from the audit process (Power 1996, 2003). ‘‘Fact building’’ is, however, an expensive process, with what gets accepted and stabilized as evidence and technique always being affected and limited by economic factors. It also requires the development of clear signs of ‘‘reasonable practice’’ designed for consumption by markets, regulators, courts of law, the state, and others (Power 1996). For Gendron et al. 2007 this process of constructing auditability involves a series of experiments conducted in what they term ‘‘occupational laboratories’’. Gendron et al. (2007) conceive of laboratories in broader terms than the prevalent image of single-site bench laboratories populated by scientists. Laboratories not only include the activities of science but also the ‘‘production and legitimization of knowledge produced in fields [such as assurance] not typically seen as scientific’’ (Gendron et al. 2007, 105–06). Hence, knowledge is seen to be produced in laboratories and through experiments that take place in everyday life as well as in self-consciously scientific sites (see also Knorr Cetina 1999) with many experiments employing trial and error processes as opposed to systematic theory. ‘‘Occupational laboratories’’ are conceptualized as everyday occupational contexts — such as professional services firms and their wider working environment — where facts and claims to expertise about new practices are produced and legitimized. Within these laboratories, audit practitioners experience considerable self-doubt and anxiety as they attempt to assemble audit technologies aimed at constructing a collectively shared sense of comfort (Gendron et al. 2007). Interactive trial-and-error experiments enrolling tacit knowledge and drawing on emotional as much as cognitive processes are deemed central to their efforts (Pentland 1993; Radcliffe 1999). While comfort can be created by selectively borrowing institutionally accepted techniques from financial audit, the limitations of these competencies can, however, quickly become apparent in the presence of auditee activities considered ‘‘soft or advisory’’ which are not easily susceptible to financial audit techniques (Gendron et al. 2007). The efforts above frequently rely on the enrollment of practitioners from diverse disciplines to form multidisciplinary ‘‘audit’’ teams. Power (1997, 1999) claims that the complexity of coordinating these different functional specialities can be underestimated, as it is often mistakenly assumed that the discrete technical practices of different disciplines will remain intact when working with other disciplinary experts. Additionally, the leaders of these processes, often accountants, may undermine other relevant expertise in an effort to claim exclusive control over new audit domains (Abbott 1988). CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1235 The audit technologies emerging from these processes eventually become codified and formalized, often in overarching methodologies, in order to provide a picture of competence by depicting evidence-gathering processes as purely rational (Humphrey and Moizer 1990). Structure is supplied to a range of technologies which are frequently negotiated, interactive, and judgmental, therefore clouding the influence of practitioner ‘‘gut feel’’ and tacit knowledge (Pentland 1993; Carrington and Catasus 2007). For Power 1995 this signifies a strategy of closure, appealing to procedure for its authority and re-presenting practitioners’ emotional responses about comfort as cognitive. This formalization may, however, incite conflict between practitioners’ individual values, emphasizing the contingent, local, and tacit, and the institutional or organizational demands for them to engage in acceptable representations of practice (Power 1997, 1999).9 The audit objectives assigned to new domains can also influence the nature of the technologies developed in ‘‘occupational laboratories’’. Power (1999) maintains that, as new audit objectives emerge, traditional ‘‘auditing’’ practices continually reassemble themselves to meet these expectations. However, the availability of appropriate technologies can also influence the overarching objectives assigned to ‘‘audit’’, with these objectives often being defined (or diluted) in ways aimed at aligning them with existing professional competencies (Radcliffe 1999; Gendron et al. 2007). For instance, the rhetoric of accountability embedded in the objectives for ‘‘audit’’ has sometimes spread well before or trailed behind available technologies. A case in point is the historically uneasy and shifting relationship between financial audit technologies and the overall goal of discovering and preventing fraud which highlights how available (and economically viable) technologies may actually shape overall audit aims (Power 1999). Audit technologies need to attain institutional credibility as technique to lend them wider support, as what ends up counting as reasonable procedure and evidence (‘‘stable knowledge’’) is grounded in an evolving practitioner consensus in which tasks and routines are given meaning within wider operational frameworks (Power 1999). As Power (1999) points out, evidence is always relative to the rules of acceptance for particular communities. Historically, accountants have attempted to sustain specific sets of practices in new audit arenas such as environmental audit (Power 1997, 2003), efficiency audit (Radcliffe 1999), and e-commerce assurance (Gendron and Barrett 2004; Shafer and Gendron 2005) by making claims as to their objectivity and universality, their essential aim being to produce and promote portable, context-free sets of ‘‘good’’ audit practices accepted as directly relevant to these new arenas. Power (2003) asserts that this abstraction has allowed accountants to claim expertise in audit domains outside of financial auditing, especially as professions invoking abstract and generalized knowledge bases have been shown to possess a key advantage over competing professions committed to producing a knowledge base tailored to different contexts (Reed 1996). Nevertheless, the apparent stability of new audit technologies and associated claims to expertise in new domains can never be construed as permanent, as subsequent challenges will inevitably test these claims further (Latour 1987; Gendron et al. 2007). Indeed, these efforts are almost always subject to contests whereby other ‘‘experts’’ challenge accountants’ claims to legitimacy (Power 1997, 1999; Gendron and Barrett 2004). For example, in the audit of government performance in Alberta, Canada, accountants promoted performance measurement practices 9. The extent to which judgment alone is relied upon has been discussed in debates about structured versus unstructured audit approaches concerning the relative balance between trust in individual practitioner judgment and the need for conformity to formal and publicly defendable rules of conduct. As Carpenter, Dirsmith, and Gupta (1994) and Curtis and Turley (2007) illustrate, structure in the form of standard operating procedures is often promoted as it enables large auditing firms to exert greater control over individual practitioners who often prefer inventive and ad hoc methods based on broad principles (Power 1999, 74; see also Gendron and Spira 2009, 2010). CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1236 Contemporary Accounting Research focused on quantitative measurement which suited their existing broad-based audit competencies in the face of considerable resistance from specialized non-accountant practitioners committed to using more contextually grounded and diverse audit techniques (Gendron et al. 2007). To summarize, the process of making new areas auditable is conceived as involving trial and error experiments aimed at simultaneously creating stable, taken-for-granted audit knowledge (audit technologies) and associated but separate auditable environments to which this knowledge can be applied. Attempts to arrive at agreed and acceptable audit technologies are often characterized by practitioner doubt, discomfort, and a considerable reliance on emotions (e.g., ‘‘comfort’’) as well as cognition. Traditional auditing practices and professional competencies are regularly reoriented to suit the audit objectives in new domains; however, where these practices and competencies seem deficient, the audit objectives may be redefined to align them with existing audit-focused competencies. Emerging audit technologies are ultimately formalized in order to present them as objective, rational, and portable, thereby contributing to their wider acceptance. The expansion of Big Four professional services firms with a core expertise in financial audit into sustainability assurance is a contemporary example of the extension of ‘‘audit’’ to new contexts and subject matters. The discussion above motivates the investigation of the following two research questions: 1. How have assurance practitioners attempted to construct sustainability assurance practice? 2. How, and to what extent, have practitioners’ efforts to construct sustainability assurance rendered sustainability reporting auditable? Before proceeding to consider the methods adopted in the study, the next section reviews the emergence of objectives for sustainability assurance from a variety of official sources. 3. The objectives of sustainability assurance The aims assigned to sustainability assurance have emanated from the accountancy profession, various standard-setting bodies, and independent institutes committed to promoting sustainable business practices.10 Prior to 2004, calls for action from the Federation of European Accountants (FEE) mapped out limited possibilities for sustainability assurance focused on providing comfort to stakeholders and management about the accuracy of reported data. Assurance statements produced by professional accounting firms also mainly concentrated on assessing the accuracy of data transfer from management information systems to sustainability reports and neglected consideration of reporting 10. The main professional accountancy and standard setting bodies articulating these aims for sustainability assurance include: the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB); the Federation of European Accountants (FEE) (FEE, 2002, 2004, 2006); and several national accountancy bodies including CPA Australia, The Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA), Royal NIVRA in The Netherlands, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) in the United Kingdom, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) and professional accountancy bodies in Germany, Sweden, and Japan (FEE 2006). More generally, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (GRI, 2006, 2008) has encouraged the provision of assurance on sustainability reports as part of its reporting guidelines. Sustainable business practices and the role of accountants therein are also being actively promoted by accounting bodies such as the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) and the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) (AICPA, CICA, and CIMA 2010). CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1237 completeness.11 In contrast, the UK-based nonprofit body AccountAbility articulated more ambitious aims centered on assessing the relevance and completeness as well as the reliability of reported information, particularly within its sustainability assurance standard AA1000AS.12 This was adopted more often by nonaccounting consultancies competing with professional accounting firms for assurance work (O’Dwyer and Owen 2005, 2007).13 The ambitions for assurance espoused by various accounting bodies and standard-setters have since broadened and now align around a suite of objectives focused on delivering accountability to stakeholders by paying central attention to assessments of the completeness, relevance, and reliability of reported information (e.g. AICPA, CICA, and CIMA 2010; Royal Dutch Institute for Register Accountants [Royal NIVRA], 2005, 2007; FEE 2006, 2009a; Royal NIVRA 2007; ACCA, AccountAbility, and KPMG 2009; ICAEW 2010a; IFAC 2011). As part of their increasing attention to articulating a role for professional accountants in the area of sustainability generally, many professional accountancy bodies and some accounting firms came to recognize that the limited aims initially assigned to assurance needed to expand and focus on stakeholder-centered issues if practice was to advance and attain greater credibility (Iansen-Rogers and Oelschlaegel 2005; ACCA, AccountAbility, and KPMG 2009). This perceived need was initially voiced as follows in a combined AccountAbility ⁄ KPMG publication: While the value of assurance to ensure reliable and comparable data for management and certain user groups still remains, today’s assurance process needs to go beyond assessments of accuracy to explore the quality of processes such as stakeholder engagement and organizational learning and innovation, as well as the way in which the organization aligns strategy with key stakeholder expectations. (Iansen-Rogers and Oelschlaegal 2005, 23) These heightened ambitions coincided with the release of the IAASB’s standard ISAE 3000 in 2004. This provides generic guidance on assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information similar to that included in the AICPA Attestation Standard AT 101 and section 5025 of the CICA Assurance Handbook (Davies and Salterio 2007).14 In 2006, FEE (2006) moved to assert that assurance should afford core 11. 12. 13. 14. Somewhat surprisingly, O’Dwyer and Owen’s 2005 survey of assurance statement content in the early 2000s found that it was assurors from outside the accounting profession who made more use of terms like ‘‘fairness’’ in their assurance opinions. Part of this trend could be attributed to caution on the part of the Big Four and other accounting firms and to companies’ requests for review-type engagements at a time when there was less attention being paid to sustainability assurance or reporting. Moreover, there was limited global professional body interest in this form of assurance prior to 2004 and ISAE 3000 had not yet been issued (the standard was issued in 2004 and came into effect on 1 January 2005). In the exposure draft stage of the Dutch sustainability assurance standard 3410N, Royal NIVRA, the Dutch accounting body, argued that the term ‘‘true and fair’’ should be reserved exclusively for financial statement audits and not be used in sustainability assurance as the term was deemed to only have a generally accepted meaning in a financial statement context (O’Dwyer and Owen 2007). AA1000AS was initially issued by AccountAbility in 2003. The standard was revised in 2008 following an extensive stakeholder consultation process. The revised AA1000AS promotes an overriding aim for assurance focused on ‘‘hold[ing] an organization to account for its management, performance, and reporting on sustainability issues’’ (AccountAbility 2008, 6). While these limited aims represent broader trends prior to 2004, there were some pioneering individuals within the accounting profession who argued for broader stakeholder-focused sustainability assurance objectives from an early stage. One early proponent of this broader perspective was Philip Wallage, a partner in KPMG Netherlands and an influential member of the Dutch accounting profession (Wallage 2000). ISAE 3000 and AA1000AS are the most commonly used sustainability assurance standards worldwide, with several professional accounting firms often using both standards in the same assurance engagements (KPMG 2008). CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1238 Contemporary Accounting Research attention to the completeness and relevance of reporting for stakeholders and called on IFAC to develop a specific international standard for sustainability assurance given what they saw as the overly generic nature of ISAE 3000 (FEE 2006, 2009a).15 FEE’s strategy on sustainability now promotes engagement with stakeholders and the need for multidisciplinary teams within assurance practice (FEE 2009b, 2009c). IFACs’ Sustainability Framework also calls on auditors to extend their role to take into account the needs of stakeholders other than shareholders and to pay greater attention to company stakeholder engagement processes in conducting assurance. IFAC further suggest that the scope and extent of assurance could be discussed with stakeholders (IFAC 2011). These stakeholderfocused trends are especially evident in standard 3410N Assurance engagements relating to sustainability reports issued by the Dutch professional accounting body Royal NIVRA (Royal NIVRA 2007) which the IAASB considered using as the basis for its proposed international assurance standard (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), 2007). The shift in assurance objectives above has been accompanied by increasing professionalization and Big Four control of the global sustainability assurance market. Up until the mid-2000s the global market for assurance was divided between a wide array of assurance providers including individuals, NGOs, engineering consultancies, management consultancies and the Big Four accounting firms. More recently, the market has come to be dominated by just three provider types: Big Four accounting firms, certification bodies, and specialist consultancies, who together control almost 90 per cent of the global market (CorporateRegister.com 2008, 34). As sustainability reports have become more significant communication documents, they have included much broader and deeper disclosures and reporters have sought to match this increasing complexity with the perceived competencies of assurance providers. In light of these reporting trends, the size and perceived reputation and assurance competencies of the Big Four accounting firms have propelled them to their now dominant position in the global market. On the supply side, perceptions of heightened assurance risk appear to have deterred many nonspecialized consultancy assurance providers whose assurance services are not a major part of their product portfolio. These ‘‘niche’’ assurance providers have largely left the market, and the trend towards Big Four provider dominance is widely expected to escalate. The International Integrated Reporting Committee’s (IIRC’s) rapidly evolving efforts to develop integrated reporting are likely to cement this dominance, as reporters may be more inclined to use their existing Big Four financial auditors to provide both financial and nonfinancial assurance given it is likely to be more cost-effective and logistically convenient (CorporateRegister.com 2008; ACCA, AccountAbility, and KPMG 2009). It is in the context of the above shifts in the objectives of and market for sustainability assurance that this study is conducted. Its focus is especially aimed at better understanding how some of the leading market players (the Big Four accounting firms) have attempted to construct assurance as the more ambitious assurance objectives outlined above have emerged. 4. Method As the research objectives for this study revolve around understanding how practitioners have come to construct assurance practice, a qualitative research approach is adopted as 15. In a roundtable discussion on sustainability assurance in November 2006, FEE concluded that sustainability assurance aimed to place core attention on the completeness and relevance of reporting for stakeholders. In a letter to Richard Howitt of the European Parliament subsequent to the roundtable, FEE emphasized the need for sustainability assurance as it would help ensure that organizations were more transparent and credible in their relations with all stakeholders. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1239 this emphasizes the description and understanding of processes, in particular the meanings individuals bring to processes in real-life organizational settings (Denzin and Lincoln 2000; Gephart 2004; Edmondson and McManus 2007; Cooper and Morgan 2008). Specifically, a series of semistructured interviews with practitioners in two Big Four professional services firms (code-named JIF and TRU for anonymity purposes) was carried out. These were supplemented by documentary (and other) evidence in order to support and contextualize the interviewees’ perceptions. The interviews were conducted in the national headquarters of both of the firms, which are located in the same city in Western Europe. The two offices were selected to serve as exemplar cases because they both provide sustainability assurance services to a range of national and multinational companies and are recognized as market leaders in sustainability assurance worldwide. The vast majority of TRU’s sustainability assurance clients are also financial audit clients, meaning that financial audit partners also act as the lead partners on sustainability assurance engagements. This situation is not as common in JIF, with most engagements having a nonfinancial audit lead partner. The respective reputation of the offices, especially that of JIF, has grown significantly over a number of years and they are recognized as thought leaders in sustainability assurance due to the extensive public comment and guidance on sustainability assurance that has emanated from both offices on behalf of their global firms. Both firms are heavily involved with key international organizations in the sustainability reporting and assurance field such as the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC), IAASB, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), AccountAbility, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). The interviewees comprised some of the most prominent and expert practitioners involved in developing sustainability assurance worldwide; hence, gaining access to their experiences contributed considerably to the quality and relevance of the data collected. For example, one of the JIF senior partner interviewees was a key driver behind the upsurge in environmental audit education and practice in Western Europe in the late 1980s and 1990s. A JIF senior manager also developed one of the first environmental audit methodologies in the mid-1990s while another JIF senior partner has been a central figure in developing the sustainability assurance market since the mid-1990s. Other JIF and TRU interviewees were involved in one professional accounting body’s attempt to develop a sustainability assurance standard. Contact with JIF was established through a senior partner who was known professionally to the author. In response to a request to study the emergence of sustainability assurance in JIF, a formal meeting was held between the author and two senior JIF partners, the head of the assurance quality review department and the head of the sustainability division. A broad framework for the study was proposed by the author at this meeting and a follow-up meeting with both partners was held to discuss the proposal in more depth. This meeting also included the other senior partner in the sustainability division at this time. A more comprehensive formal proposal was subsequently sent to the lead partner in the sustainability division, and after some additional interaction via email this partner approved interviews with key JIF staff. All interviewees were then selected and contacted by the author and all interview requests received a positive response. Contact with TRU was initiated through two postgraduate students who were completing internships within TRU and through email requests sent to a senior director and senior associate requesting interviews, all of which received prompt and positive responses. As noted above, the data analyzed for the study was collected from numerous sources. These included the two initial joint interviews with the senior partners in JIF, 20 separate in-depth interviews held with twelve key members of the JIF Sustainability division directly engaged in sustainability assurance (see Table 1), and 14 interviews with the five key individuals engaged in sustainability assurance in TRU (see Table 2) (36 separate CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1240 Contemporary Accounting Research TABLE 1 JIF interviewee details ‘‘Accountant’’ Yes ⁄ No Position in JIF Sustainability Division JA No Senior manager JB Yes Senior partner JC Yes Senior partner JD JE JF No No No Manager Manager Senior partner JG JH JI JJ JK JL No No No No No No Manager Manager Manager Senior Senior Senior Interviewee Date of interview Interview duration (minutes) 1. December 2005 2. September 2006 3. September 2007 4. September 2008 5. July 2009 6. August 2010 1. May 2005 2. September 2005 3. March 2006 4. December 2008 1. May 2005 2. September 2005 3. April 2006 4. December 2008 5. September 2010 March 2006 March 2006 1. September 2005 2. May 2006 June 2006 June 2006 April 2006 May 2006 April 2006 June 2006 90 35 45 65 85 45 90 95 75 120 90 95 70 120 30 65 70 95 85 65 55 45 50 65 105 Notes: The interviews comprised two joint interviews (with interviewees JB and JC in May 2005 and with interviewees JB, JC, and JF in September 2005) and 20 individual interviews, giving a total number of 22 separate interviews. ‘‘Accountant’’ refers to a trained financial auditor (i.e., the interviewee has a professional accounting designation). ‘‘Nonaccountant’’ refers to an assurance practitioner who is not a trained financial auditor (i.e., the interviewee has no professional accounting designation). interviews in total). The JIF interviewees comprised senior partners (three), managers (six), and seniors (three). Only two interviewees from JIF, both senior partners, had training in financial auditing (collectively labeled ‘‘accountants’’ for the purposes of differentiation in the paper’s analysis), the assurance quality review partner and the head of the sustainability division. The other interviewees had prior training and experience in environmental management, environmental economics, business ethics, sustainability management, and cultural anthropology (these interviewees are collectively designated as ‘‘nonaccountants’’ for the purposes of differentiation in the paper’s analysis). The TRU interviewees were comprised of a senior director, senior associate, manager, senior, and senior partner in its sustainability division. Two of these five interviewees had training in financial auditing CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1241 TABLE 2 TRU interviewee details Interviewee ‘‘Accountant’’ Yes ⁄ No Position in TRU Sustainability Division TA Yes Senior Director TB No Senior Associate TC No Manager TD Yes Senior TE No Senior Partner Date of interview Interview Duration (minutes) 1. April 2008* 2. May 2009 3. June 2009 4. August 2009 1. March 2008 2. June 2009 3. August 2009 1. April 2008 2. June 2009 3. July 2009 4. September 2010 1. March 2008 2. May 2008 May 2009 35 50 50 35 85 45 70 50 65 50 30 90 35 50 Notes: ‘‘Accountant’’ refers to a trained financial auditor (i.e., the interviewee has a professional accounting designation). ‘‘Nonaccountant’’ refers to an assurance practitioner who is not a trained financial auditor (i.e., the interviewee has no professional accounting designation). * Extensive follow-up email correspondence also occurred in late April 2008 as the initial interview had to be curtailed. (‘‘accountants’’) while the remainder comprised business ethicists and ‘‘sustainability experts’’ (‘‘nonaccountants’’). All TRU and JIF publications relating to sustainability assurance were also analyzed. These were comprised of copies of presentations relaying the assurance process (JIF), publications commenting on extant sustainability assurance standards (JIF and TRU), ‘‘sustainable development’’ strategy overviews for clients (JIF), and publications issued outlining both firms’ approach to and perspectives on sustainability assurance (JIF and TRU). TRU also allowed a supervised viewing of their initial sustainability assurance methodology template that was being introduced to structure assurance engagements at the time of the first round of interviews.16 All interviews lasted from 30 minutes to two hours. For JIF, they took place over the period December 2005 to September 2010. An initial series of interviews was held from December 2005 to June 2006 focused on understanding, from the perspective of practitioners, how assurance had evolved in JIF since it was first introduced. Contact was maintained with many of these interviewees over the next five years (approximately) through informal discussions, email exchanges, and meetings at conferences relevant to sustainability assurance as the assurance market began to expand in conjunction with numerous developments at the professional and standard-setting level. Notes were kept of all discussions over this period. Key JIF contacts were also reinterviewed during this period to ascertain any developments that had occurred in practice over the period in response to the wider developments. This longitudinal focus was essential to the study’s objective to 16. Actual audit working papers were, however, not reviewed in either firm. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1242 Contemporary Accounting Research trace and understand the evolving construction of practice. Interviewing in TRU did not commence until April 2008, given its later emergence into the sustainability assurance market, and interviews ended in September 2010.17 All interviewees were sent a list of broad open-ended questions in advance of their interview encouraging them to discuss their experiences of and views on sustainability assurance practice both generally and specifically within their firms. All first round interviews investigated two broad themes: the perceived purpose of sustainability assurance and assurors’ experiences of the evolution and enactment of the sustainability assurance process within their firms. The second theme was examined within several overlapping subthemes aimed at uncovering perceptions on: the nature of the evidence-collection process; the evolution and nature of client-assuror relations; practical complexities involved in conducting assessments of reporting completeness, stakeholder responsiveness, and materiality; the key decision-making processes during assurance engagements; the nature of the assurance statement drafting process; and post-assurance interaction with clients and their stakeholders. A final theme addressed the key dilemmas ⁄ difficulties encountered by interviewees while undertaking assurance engagements.18 Follow-up interviews focused on understanding developments in practice since the initial interviews and sought to clarify key themes emanating from an initial analysis of the earlier interviews. At the beginning of each interview, interviewees were asked if it was permissible to record the interview. It was explained to each interviewee that the recorder was only being used to enhance the accuracy of the interview record, and that if at any stage during the interview they wanted the recorder switched off the interviewer would do so. All interviews, apart from the two initial joint interviews with senior partners in JIF, were recorded on an MP3 player and subsequently fully transcribed. A commitment to the confidentiality of interviewee perspectives was relayed at the beginning of each interview. Throughout the interviewing process, the themes mentioned above were used in a loosely guided manner that allowed the interviewer to remain open to pursuing emerging trends, themes, and patterns within interviews which were of importance both to the interviewees and the focus of the study (Gendron 2009; Silverman 2010). The sequence in which issues were addressed varied throughout different interviews (Patton 2002) but the same issue (the perceived purpose of sustainability assurance) was addressed at the beginning of each interview. Detailed notes were taken throughout all interviews, and after each interview finished reflections and issues for probing in future interviews were recorded on the MP3 player and ⁄ or written down in a separate journal. The transcribed interviews were analyzed using three subprocesses: data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing ⁄ verification (O’Dwyer 2004; Irvine and Gaffikin 2006). The analysis initially separated the TRU and JIF interview data.19 A detailed reading and subsequent coding of all transcripts and accompanying notes and tape-recorded reflections on interviews led to the identification of numerous key themes within each set 17. 18. 19. The study did not gather observational data on the work of assurors on actual assurance engagements (e.g. Pentland 1993; Radcliffe 1999; Barrett et al. 2005). Hence, while repeated interviewing and documentary analysis was conducted to build a coherent picture of emerging issues and practice, the use of observational data may have provided additional insights into the interactions among assurors and the nature of their decision-making processes on assurance engagements. These interview themes also formed the basis of the interview schedule used in O’Dwyer et al. 2011, which draws partly on a separate and distinct analysis of 14 of the 22 JIF interviews. A separate paper was prepared from an analysis of 14 of the 22 JIF interviews. This latter paper (O’Dwyer et al. 2011) drew on aspects of the JIF data with a distinct theoretical and empirical focus from this study. O’Dwyer et al. 2011 illuminate the processes through which assurance practitioners in JIF have sought legitimacy for sustainability assurance with key internal and external audiences and place a core emphasis on examining the processes through which sustainability assurance statements are constructed. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1243 of interviews related to the construction of assurance in both firms. A summary matrix was then prepared for each transcript which highlighted themes focused on the construction of assurance, and explained the nature of the themes and their location within each transcript. Extensive comparison of thematic matrices across interviewees and between firms was then undertaken. Subsequent readings of the transcripts added to these themes and a theme-led ‘‘thick description’’ of the findings was then prepared. This description was subsequently considered in conjunction with emerging public documentation on assurance produced by JIF and TRU and the other documentary evidence gathered. Drafts of findings were fed back to interviewees over the study period and certain key findings were probed further in later interviews with key contacts. A formal presentation of key aspects of the overall findings was also presented at an academic ⁄ practitioner forum and this elicited positive feedback from a variety of international practitioners (including representatives from both firms) who indicated that the issues raised reflected many of their experiences. Repeated drafting, reanalysis, and interaction between the data and the key literature used to frame the study (namely, Pentland 1993; Power 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003; Radcliffe 1999; Gendron et al. 2007; Free et al. 2009) occurred over an extended period to inductively derive the case analysis in section 6 below. 5. Case context The two Big Four professional services firms studied (JIF and TRU) operate within the same national Western European context and are headquartered in the same city. Both firms have a range of national and multinational sustainability assurance clients. JIF is the more established practice and has provided assurance on sustainability reports (or their equivalent) on a range of multinational clients headquartered in its home country and is the recognized market leader in this context. The Sustainability Section in JIF is a key part of the firm’s global sustainability network connecting member firms globally. TRU has been involved in sustainability assurance for approximately seven years, has gained increasing market share since 2006, and now has a number of multinational clients. Sustainability assurance practitioners in both firms operate within wider sustainability divisions that also focus on providing a range of advisory services to companies on sustainability-related matters. Partners in both firms have played leading roles in the development of international firm-wide practices. The assurance team in JIF was significantly expanded when a number of sustainability assurance and advisory practitioners joined the practice in the late 1990s. This practitioner group was led by a key player in the accountancy profession involved in the development of sustainability accounting and assurance in Europe (he had departed JIF at the time this study commenced). The new group helped develop a stand-alone sustainability division in JIF and integrated existing nonaccountant assurance staff into this division. The initial chair of JIF’s global sustainability division was also a partner in the JIF office studied, and the majority of assurors were nonaccountants. There is a clear separation of sustainability assurance from financial audit within JIF, and while financial auditors work on many engagements dedicated sustainability assurance practitioners lead these engagements. TRU’s assurance practice also sits in its ‘‘sustainability division’’, which provides a range of other advisory services to clients. Assurance practice has emerged gradually within client contexts where advisory services related to sustainability initially predominated. Four individuals at manager ⁄ senior level work exclusively on sustainability assurance with other individuals in the division engaging in assurance in conjunction with other advisory roles. Financial auditors are also assigned to the division for one or two days a week and work on assurance engagements but are not deemed part of the core staff of the division. TRU encourage a mix of financial auditor and dedicated sustainability assurance CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1244 Contemporary Accounting Research expertise on all engagements. The senior partner in the division, who is not a financial auditor, oversees all sustainability division work but all other lead partners on sustainability assurance engagements come from financial audit. Sustainability assurance-focused documentation publicly circulated by both firms also articulates the broader objectives for assurance promoted by professional accounting bodies and standard-setters as outlined in section 3. For example, both firms refer to the core contribution sustainability assurance can make to organizational accountability and to the credibility users can glean from information that has been assured, especially regarding its relevance and reliability. JIF claims that an assurance provider has a ‘‘duty’’ to assess the completeness of a sustainability report — that is, whether the important ⁄ relevant issues are addressed in the report — regardless of whether they are strictly required by rules and regulations. TRU contends that assurors can and should provide assurance not only on the accuracy but also on the completeness of reported data to enable more ‘‘meaningful’’ accountability to stakeholders. The firms emphasize their commitment to assessing reporting completeness by suggesting that the entire sustainability report should be included in the scope of every assurance engagement. 6. Case analysis This section presents and analyzes the case findings. The first subsection reveals the nature of assurors’ commitment to the stakeholder-focused ideals now widely espoused for sustainability assurance in much of the professional literature, as this allegiance is likely to influence how they approach the construction of assurance practice (Pentland 2000). The second subsection explores the initial complexities involved in constructing practice in the context of perceived diverse, vague, disconnected data, particularly the difficulties involved in assessing reporting completeness, a core objective assigned to sustainability assurance. The third subsection illustrates how the distinct habits and routines of ‘‘accountants’’ (trained financial auditors) and ‘‘nonaccountants’’ (other assurors not trained in financial audit) have clashed as efforts to construct practice have evolved, thereby triggering tensions in the development of approaches to the ‘‘audit’’ of certain data. In light of the assuror struggles with data, attempts by both firms to structure emerging practices in broad methodological ‘‘shells’’ are unveiled in the fourth subsection but are widely perceived to have had limited impact on actual practice ‘‘on the ground’’. The final subsection illustrates how both firms have come to publicly recognize the limitations of traditional financial audit techniques in fulfilling the key assurance objective of assessing reporting completeness, while simultaneously suggesting a solution which enrolls stakeholders into the sustainability reporting and assurance process. Assuror-espoused ambitions for assurance Throughout their reflections on their experiences of practice, seniors, associates, and managers in both firms, particularly nonaccountants, emphasized their personal and professional commitment to holding companies to account on behalf of wider stakeholder groups. Senior partners, however, while emphasizing their professional responsibility to stakeholders ⁄ readers, viewed their role in more dispassionate terms and were less inclined to link their professional and personal motivations. Several nonaccountant managers insisted that they were ‘‘working for the readers’’ (TB20 — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2008) of sustainability reports and claimed that 20. Please refer to the interviewee codes in Tables 1 and 2. References in brackets in the case analysis after interviewee quotes [for example, (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2007)] refer to: 1. the interviewee’s code from Table 1 and 2 (e.g., JB); 2. the interviewee’s job title and ‘‘accountant’’ or ‘‘nonaccountant’’ designation (e.g., senior partner (accountant)); and 3. the year the interview was conducted. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1245 their admittedly ‘‘idealistic view of sustainability’’ (JI — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) reflected both a personal and professional commitment to ‘‘selling sustainability as a concept centered on a core concern for stakeholders’’ (JI — manager (nonaccountant), 2006). One JIF manager indicated that his career choice was motivated by a desire to ‘‘help and create change in society and to have a little role in making business more accountable for their impacts and therefore more sustainable’’ (JD — manager (nonaccountant), 2006). He felt that sustainability assurance could help ensure that companies ‘‘filled a broader role within the context of what society expected of them’’. These ambitions led to some nonaccountants harboring ambitions for assurance consistent with their personal commitments, sometimes irrespective of the objectives attached to individual assurance assignments. Senior partner (accountant) assurors were careful to curb what they viewed as certain nonaccountant ‘‘activist’’ tendencies. For example, a JIF senior manager’s apparently ‘‘extreme’’ commitment to a stakeholder-oriented view of assurance resulted in him being ‘‘sidelined’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2005) in one assurance assignment as senior partners considered him overly critical of the quality of a client’s stakeholder engagement process. This conflation of professional rationales with commitments to ambitious assurance objectives reveals the apparently self-selecting nature of several assurors in this domain. Moreover, as we shall see, this fusion influenced the manner in which some of these interviewees instinctively approached their work. Experimenting with assurance technologies The development of technologies providing assurors with specific mechanisms to tackle data in sustainability reports has evolved in an iterative manner through various on-site experiments characterized by trial and error and improvisation. Many assurance engagements in JIF emerged in the 1990s from companies required to comply with local environmental reporting regulations. Engagements also emanated from multinational companies who were initiating sustainability reporting for the first time but were keen to ensure that they could be confident about any information they issued publicly.21 In TRU, several assignments emerged from existing national and multinational financial audit clients who had commenced producing sustainability reports in response to international trends. Hence, in both firms, assurance assignments were initially, albeit not exclusively, designed in response to a perceived market demand which both firms subsequently sought to further stimulate. Coping with discomfort: Diverse, vague and disconnected data More experienced assurors, particularly in JIF, revealed how documentation of processes and procedures in the early years of assurance was minimal as assurors experimented with testing procedures. They often entered ‘‘unknown ground’’ (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2005) and experienced ‘‘heightened levels of uncertainty’’ (JA - senior manager (nonaccountant), 2006) and discomfort, given a lack of formal internal or external guidance. Certain seniors and managers claimed that this uncertainty initially led to excessive amounts of work being conducted, given the lack of uniform assurance approaches and insufficient knowledge of sampling procedures among nonaccountants: When it comes to documenting and having an electronic file which is up to standard, we have come a long way. I know how I was struggling with the [name of large client] file, 21. As noted in section 5 above, new clients were also acquired by JIF when a number of sustainability assurance and advisory practitioners joined the practice in the late 1990s and brought their existing clients with them to JIF. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1246 Contemporary Accounting Research because that was really my first experience with a major sustainability assurance engagement and I did not really understand what had to be done and there were no accepted standards or guidance . . . . The practical aspects of documentation were actually the most challenging to learn and master. This is not to say that the work we performed in the first couple of years was not up to standard, but it was just not up to our current standard. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2008) Starting off, we weren’t really sure what to do actually, especially on early [assurance] assignments and strangely enough our reaction was, in many cases, to overdo it, by requesting a lot of documentation and support without relying on samples as much as we do now. Much of it was seat-of-the-pants stuff so we tried to cover ourselves as much as possible without annoying clients too much. (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2008) Certain claims in sustainability reports caused deep discomfort as ‘‘excessive reliance on professional judgement’’ (TD — senior (accountant), 2008), rarely backed by extensive prior experience, necessarily drove assessments of this data. For example, claims by companies to have implemented codes of conduct required not merely identifying the existence of codes but also developing reliable processes to gain assurance that implementation was actually taking place company-wide. This involved local site visits to assess if employees were aware of codes and whether they had seen and read code manuals. However, many assurors claimed that site selection rarely followed consistent sampling criteria while conclusions were too often based on ‘‘hunches’’ drawn from extensive observation and interviews. These hunches became the primary means through which many assurors initially came to feel comfortable about the reliability of their sample selections. Companies were also prone to using vaguely defined terms in their sustainability reports. Senior partners and associates in both firms contrasted this with the relative uniformity and comfort provided by financial reporting data. The TRU manager (nonaccountant) recounted one company claiming that they had ‘implemented human rights policies’ without providing any further clarification or support. He relayed his efforts to establish agreed definitions of terms like ‘‘human rights’’ and ‘‘policies’’ to create some form of auditable environment with respect to these terms. He then had to develop assurance procedures tailored to assessing ‘‘implementation’’ in the context of these definitions. While bemoaning the lack of formal guidance he emphasized that this was just one example of many where tests had to be continuously constructed given the varying nature of the data assurors were confronted with. Constructing auditable environments: The necessary combination of assurance and advice The senior partners and director with financial audit backgrounds contrasted the relatively complex nature of sustainability data with financial accounting data. The lack of linkage in social and environmental data caused significant discomfort regarding the auditability of reporting completeness. Standard compliance-testing procedures struggled to cope with this lack of linkage, given the stand-alone nature of sustainability report data. This lack of linkage was also compounded by the rather rudimentary data collection systems initially employed by some companies, thereby amplifying the need to create more auditable environments: With financial accounting information all the data is linked together so there is always a link with another piece of information. If you look at financial audit where you have completeness of purchases, it is easy in the sense that you have purchases and sales and you can relate them to one another, you have all your processes and systems. You will CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1247 see issues in your margins if the purchases aren’t complete. (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2005) Most of the time there are no good systems for sustainability reporting. You have to realize that most of the companies collect and analyze their data in Excel sheets; these are e-mailed from one country to the head office and at the head office the data is consolidated. This does not necessarily mean it is wrong, but it is very different compared to a screened system. There are often no procedures that specify which data is reported, where to look next to or how to compare the data with last year. The whole control environment is different in this world and that is the biggest challenge. (TA — senior director (accountant), 2009) CO2 emissions are primarily focused on trying to report lower emissions or lower accident rates but it is stand-alone information and you often have little to relate it to if the systems are poor. There is also less scope for substantive testing as there is no invoice or signature like in a purchase. (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2006). When assuring on safety incident reporting some managers claimed that they also needed to assess a company’s organizational culture, especially the nature of its reactions to incidents, which ‘‘involve[d] huge amounts of hunch and judgement’’ (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2006), as well as on-site presence. Year to year data trends also posed significant problems as comparability was complicated by companies constantly changing their measurement methodologies without explanation and reporting comparative figures such as CO2 emissions derived from different methodologies. Assurors had to take great care to ensure consistency in methodologies when assessing trends and this led to frictions with some clients: You had situations where increased measurement resulted in what appeared to be a decrease in emissions. If we had a measurement estimate which was very inaccurate, you had a measurement two years later which was much more accurate and it’s ‘‘oh, our emissions are only this much and we’re showing a graph like this’’. And I said ‘‘no, the emissions weren’t in your file two years ago, you’ve just changed your methodology’’. So again, they would have to alter the notes in the packs and the notes to the graphs to indicate that that decrease was a result of the change of methodology. (JH — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) Given these weaknesses in supporting information systems, many nonaccountant managers and seniors claimed that engagements embraced ‘‘a natural advisory element’’ (TC — manager, 2008). This facilitated the construction of auditable environments through the provision of advice on the implementation of better information systems, processes and controls. It was also evident in recommendations in assurance statements aimed at improving internal control systems: I think it is quite logical to approach assurance from an advisory perspective. This is a very advice-oriented market and it is also my personal ambition to provide advice where I can. Of course you do assurance and you do it from the perspective of an independent assurance provider, but in the process of doing this assurance you are also the natural advisors to the client, and you help the client by providing best practices, by giving second opinions and showing them different ways of organizing their reporting process. That is very important, because that is really what the clients pay for. They do not pay for the final signature. They want to make sure that they have a report that adds value CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1248 Contemporary Accounting Research to their stakeholders and so do I. You could say that it’s not your job as an assurance provider, but from a market point of view, I think that clients really do expect this from us. (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2009) While this advisory focus allowed assurors to encourage changes in organizations focused on providing more relevant and reliable information for stakeholders, it also potentially undermined their independence. However, interviewees at all levels in both firms were highly sensitive to and dismissive of these potential independence concerns. Managers emphasized a clear distinction between advice and implementation, while senior partners and associates referred to their required compliance with ethical guidance from the accounting profession — something which was also seen as an effective marketing strategy central to increasing both firms’ external credibility in the sustainability assurance market: Independence is not really a problem because we have been made so aware of the importance of ensuring that [TRU] doesn’t get a bad name that we are pretty serious with the client. I mean, you can still have a good relationship with your client and besides answering all the questions about the assurance process you can still be an expert. You can still say things like ‘‘you should have a look at that report’’, or, ‘‘have a look at that website’’, or, ‘‘I’ll send you a link with three perspectives, see if you can do something with them’’, that kind of thing. We are not going to recommend a business control manual. But we give them maybe three good examples or we give a second opinion on what they have put together or we join them in a brainstorming session. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2008) The limits to auditability: Complexities in assessing reporting completeness and relevance The concerns about auditability became acute when assurors experimented with assessing reporting completeness and relevance. Completeness assessments were widely viewed as a ‘‘very grey area’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2005) replete with frustrations associated with developing not only feasible, defendable formal technologies per se but also economically realistic ones. For example, the expansion of reporting to encompass social as well as environmental issues often meant that more site visits were required within tight budgetary constraints while the absence of sufficient expertise in other national offices meant that direct site visits were often required by TRU and JIF staff in the two offices studied, thereby driving up costs: A country with large emissions might not be the country you want to look at for human rights, so you end up with a very difficult balancing act once you spread to assuring on social issues. (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2007) With sustainability assurance most of the work is done by us [the TRU office]. This is because people in [TRU] in, for example, India are not aware of sustainability. And even in Belgium, if that office is less engaged with sustainability issues then it is difficult to let them do the work. (TA — senior director (accountant), 2009) The often ambiguous, nonuniform criteria for site selection, particularly by nonaccountant assurors with limited knowledge of sampling procedures, proved especially frustrating for partners, managers and seniors as many non–Big Four competitors were perceived as undertaking less assurance work. While techniques such as Internet searches, peer review processes, media analyses, and liaison with financial auditors were mobilized to assess reporting completeness, a number of managers and seniors complained that they were uncomfortable about the extent of reliance they could place on them. They felt that CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1249 they engaged in ‘‘too much interpretation’’ (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) which was partly necessitated by a lack of clear guidance in existing standards: I mean in some cases assessments can be very personal, you actually feel personally that something should be included in the report but you don’t have any evidence to substantiate it so you may mention it face to face to the company but not include it in your assurance report. But it is really subjective and you rely a lot on gut instinct especially with regard to assessing completeness of disclosures on supply chain issues. (JG — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) Assurance on completeness is vague because the regulations and standards are not that clear that they can serve as a grip. They don’t tell you exactly where to look, what to do exactly or how to handle things in practice. There is so much room for interpretation. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) The absence of guidance as to what level and type of work was required to support limited or moderate assurance opinions on reports was a particular frustration for several senior partners, directors and associates. A JIF manager also complained that while he was ‘‘irritated’’ by the fact that he had little guidance on ‘‘what w[as] needed to go to a higher level of assurance’’, what was more annoying was that he ‘‘found it most embarrassing that [he] could not explain it to [his] client[s]’’ (JE — manager (nonaccountant), 2006). To be honest, what is moderate? What is moderate level assurance? How much do we have to do in a CO2 or in a human rights environment to get a moderate level of assurance? It is very vague what the differences are between the levels of assurance. (JC — senior partner (accountant), 2008) What is limited assurance? Well, you can do nothing and you can still give limited assurance. If you look at the wording of the [limited opinion] conclusion, you can do only some work at the corporate level and then still only provide limited assurance. (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2008) This perceived obscurity of the link between levels of assurance and the cost of work to be done heightened this ambiguity and uncertainty, thereby sometimes placing assurors in what Power (1999) deems an essentially unknowable situation: I have to say that there is a general concern about whether we are capable of auditing the really important information and the really important issues. This is, at the moment, irresolvable because no one has the answer. (JB — senior partner (accountant), 2008)22 The limits to auditability: Politics and substandard stakeholder engagement Completeness assessments were further complicated as assurance scope and related site selection decisions could be highly political in character given some client concerns to restrict scope and eliminate certain areas from inquiry. For example, clients sometimes 22. ISAE 3000 and the IFAC International Framework for Assurance Engagements both define and distinguish between two types of assurance engagement that IFAC members are permitted to perform: ‘‘reasonable assurance engagements’’ and ‘‘limited assurance engagements’’. AA1000AS, however, adopts the descriptors ‘‘high assurance’’ and ‘‘moderate assurance’’, thereby possibly adding to the challenges referred to by practitioners. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1250 Contemporary Accounting Research only wanted assurance on areas where they could indicate positive performance; hence, the aforementioned importance of carefully assessing data trends. This challenged both firms’ public commitment to assurance aimed at assessing the entire sustainability report and not merely client-selected segments of it. It also led to both firms declining engagements where they felt the reporting company was trying to overly limit the scope of reporting. A fundamental factor exacerbating these perceived problems was the initial limited nature of client stakeholder engagement processes, which many interviewees felt contrasted with the corporate public rhetoric surrounding them. Several senior partners, seniors and managers insisted that the absence of core auditable stakeholder engagement mechanisms was a key challenge for future assurance practice if assurors were to be able to adequately assess reporting completeness and relevance: I am surprised and disappointed that many companies do not [place] more attention [on] [external] stakeholders. Their reports are always written from the inside out and not from the outside in. (JJ — senior (nonaccountant), 2006) Companies are not checking with the outside world ‘‘what do you want to have assured and to what level? What’s your real concern with our report?’’ They need to do more with stakeholders and find out their needs or at least try to find out. (TD — senior (accountant), 2008) Moreover, even where stakeholder engagement processes existed, they were often not adequately documented to allow for an independent assessment of their content. Assurors also bemoaned the absence of clear guidance from existing standards on the procedures necessary to provide assurance on these processes. Several interviewees complained that ‘‘ISAE 3000 only refer[red] to stakeholder engagement in one sentence’’ (JG — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) while AA1000AS was criticized for being too broad and aspirational to reliably guide practice. Its stakeholder focus was also only ‘‘good and fine if you had decent levels of stakeholder engagement by companies’’ (TA — senior director (accountant), 2008), a situation that, according to one JIF interviewee, initially applied to ‘‘only one per cent of [his] clients’’ (JE — manager (nonaccountant), 2006): I do not trust standards like AA1000 and ISAE3000 because I have been listening to talks and discussions around such standards for years now and I haven’t seen anything that I can use in practice. Given the poor stakeholder engagement practices of a lot of our clients, while it is important to take into account the stakeholder view, in general it is proving difficult to make it a framework for conducting assurance . . . at least it doesn’t work for us.23 (JE — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) Differing approaches approaches to practice to auditability: Harnessing accountants’ and nonaccountants’ The fragile nature of the experiments described above aimed at simultaneously producing audit technologies and auditable environments was aggravated by the need to harness the mindsets of nonaccountant and accountant assurors. Both firms’ promotional documentation on assurance, as well as standards and calls for action from professional accounting and standard-setting bodies, emphasize the necessity and desirability of 23. This interviewee was referring to the (original) 2003 version of AA1000AS. This was revised in 2008. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1251 mobilizing multidisciplinary teams. However, the coordination of multidisciplinary practice has exposed some tensions between assurors, which was evident in their contrasting conceptions of how comfort could be constructed from assessments of (qualitative) data. As mentioned in section 5 above, a number of nonaccountant assurors with significant prior experience of assurance on environmental reporting joined JIF in the late 1990s. The existing financial auditors in JIF had ownership of one large sustainability assurance client (code-named PMP) and the newly arrived nonaccountant assurors brought other key clients with them and significantly expanded the assurance market over the ensuing years. Initially, distinct approaches to assurance became evident with several nonaccountant assurors interviewed expressing discomfort at the restricted scope assurance approach adopted by PMP’s accountant assurance team. According to them, the financial auditors were ‘‘somewhat timid’’ as their engagements only focused on assessing key numerical indicators determined by PMP which were easily amenable to conventional substantive testing procedures aimed at assessing quantitative data accuracy: [PMP] is a different story as it is actually being done by [JIF] accountants and is not a real sustainability assurance engagement. (JD — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) Hence, when accountants and nonaccountants in JIF eventually commenced working together on assurance assignments, distinct mindsets surrounding assurance practice emerged. These distinctions were particularly apparent in nonaccountant assuror perceptions of the way in which financial auditors approached the judgement of data, which the nonaccountants claimed was too heavily influenced by ‘‘a structured, inflexible mentality’’ (JI — manager (nonaccountant), 2006). Indeed, it was alleged that financial auditors in both firms followed standard substantive and compliance testing procedures far too rigidly. This apparently led to constrained ways of thinking about and approaching data, which nonaccountant seniors, managers, and associates felt uncomfortable with. For example, one JIF senior manager complained that financial auditors ‘‘had insufficient knowledge of the subject matter in [sustainability] reports to judge the work of experts [nonaccountant assurors]’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2008) and gave insufficient attention to the complexity of the context within which data was created. Competing accountant and nonaccountant conceptions of materiality caused particular frustration, with nonaccountants defending the importance of informed assessments ‘‘of stakeholder materiality or completeness’’ which they claimed ‘‘financial audit guidance d[id] not handle well’’ (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2008): I’ve seen accountants put lines of figures from one year and the next year and do a comparison and come up with [a conclusion] stating ‘‘well this is material because there’s been a 100 per cent change’’, and I’ve said ‘‘yes but that’s an entity that had two accidents last year and it had four this year and you’re saying that it’s material because it’s a 100 per cent change’’. I said ‘‘you’ve got twenty entities in developing countries that have reported zero both years and you’re saying they’re not material. Does it not strike you that they might not actually have any systems in place to record this information locally or that systems might have changed in both years?’’ So it’s a completely different attitude. If you just give an accountant a list of figures and say ‘‘you do your site selection based on these figures’’ they come up with all the wrong selections. (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2006) Materiality is totally different in sustainability reporting [compared to] financial reporting. [Name of client], for example, may look at how many accidents have happened in CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1252 Contemporary Accounting Research its work force. An accountant would say we have five per cent materiality meaning 800,000 multiplied by 0.05 equals 40,000 people and we would be told that there is no problem. But in the real world when [name of client] has one heavily injured employee this would cause great problems. Moreover, if we do assurance on fatalities, we are not going to say that the materiality levels are five per cent of overall fatalities based on historical data. Every fatality is material. However, this is something we have many debates on with our financial assurance colleagues. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) For most nonaccountant assurors, evaluating social and environmental data, especially its completeness, was unavoidably reliant on informal, contextually grounded, judgmental assessments based on knowledge accumulated over time. The ability to apply this knowledge, however problematic and uncertain, was what made sustainability assurance compelling and challenging for them. Accountants were also seen to be reluctant to go ‘‘into the field’’ (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2008) to assess the processes driving reported data, thereby placing too much emphasis on assessing data received directly from clients using traditional substantive testing. This was especially apparent when assessing claims related to the integration of so-called ‘‘values’’ in organizations, which involved greater ‘‘subtlety and risk’’ (JJ — senior (nonaccountant), 2006) and ‘‘on-site presence’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2007) than distanced evaluations of quantitative data produced by clients. These perceptions correspond with Gendron et al.’s 2007 discovery of contrasting approaches to the audit of government performance by program evaluators and auditors of the Office of the Auditor General of Alberta (‘‘the Office’’) in Canada. Here, program evaluators believed that government performance could only be conceptualized and audited by focusing on contextual, tailored, and qualitative measures of effectiveness (Gendron et al. 2007), while the Office auditors enrolled selective techniques from financial auditing (and accounting) which the program evaluators dismissed as superficial. The senior accountant partners in JIF and TRU acknowledged many of the tensions above but defended the need for an audit approach that sought more focus and certainty in testing as well as greater conformity with standard approaches to assurance within both firms. The financial audit senior in TRU (TD — senior (accountant), 2008) recognized that she had a very different mindset to many of the nonaccountants and was somewhat surprised by the level of expert knowledge and commitment displayed by some of her nonaccountant colleagues. However, she insisted that her way of thinking was essential to ensuring that nonaccountants conducted defendable testing that complied with firm-wide procedures. For her, financial auditors brought greater organization and structure to assurance engagements and were more realistic about the extent to which issues surrounding reporting completeness could be reliably assessed. She also claimed that financial auditors were at a disadvantage as they were working on both financial and nonfinancial assurance engagements and it was natural that they should bring the customs and habits of financial audit to sustainability assurance. Moreover, while nonaccountant assurors often felt that assurance and advice could easily overlap, her training had taught her to be wary of any such possibility, which alerted her to the necessity of ensuring that nonaccountants did not breach independence requirements. Despite the tensions, many nonaccountant assurors also acknowledged the positive influence of accountants in enabling them to organize and document their procedures in a more defendable and professional manner. In particular, despite some of the aforementioned disagreements over sampling, some nonaccountants indicated that they had learned a lot about certain data sampling procedures from accountants that allowed them to approach aspects of their work more effectively and efficiently: CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1253 When sampling I am always happy that we have mixed teams. We often have regular accountants who work together with specialists . . . . You see, I still don’t know anything about sampling and how large the random check has to be and when you must dismiss something and when you can add ten more in order to be okay. For that sort of thing I always ask the accountants. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) Within TRU, financial auditors initially led the development of practice but, as with JIF, this was initially consigned to assessments of data accuracy within environmental reports. As engagements developed and reports evolved to encompass both environmental and social data involving greater textual, ‘‘softer’’ content, ‘‘advisors’’ from the sustainability division were drafted onto assurance teams and assigned to provide assurance on data such as company claims which financial auditors appeared less comfortable with. Gradually these individuals assumed the management of these engagements, but despite this they sometimes worried that assurance work remained too focused on data accuracy alone given the overriding influence of lead financial audit partners. Consequently, in TRU much more so than in JIF, financial auditors remained the leaders of sustainability assurance practice despite their lack of comparative ‘‘expert’’ knowledge of the sustainability field. However, while Gendron et al. (2007) found that the program evaluators in Alberta were effectively marginalized by Office auditors, the nonaccountant assurors in TRU claimed that they constantly challenged financial auditors’ work. For example, when confronted with the need to provide assurance on claims that had been directly copied from annual financial reports into sustainability reports, they insisted on their need to ‘‘audit’’ these claims. This often annoyed clients and financial audit lead partners, who maintained that, as the claims had already been reviewed for consistency with the financial statements by the financial auditors, this was unnecessary: Just recently I was in a situation where I did the audit of a sustainability report for a client who is also an accountancy [financial audit] client for us. This particular company had copied complete [sections] from their annual report into their sustainability report. In those [sections] the company made quite substantial claims like ‘‘we are the best’’ and things like that. We would challenge that. We would require some supporting evidence for claims like that, while the financial auditor would already have signed off on the [annual] report and not asked any questions on the text. What they do is simply read it and make sure that there is nothing contradictory to the annual financial statements. This client just could not understand what we were doing, while I think for a sustainability practitioner [nonaccountant] it is quite obvious that if you say in a report that you, for instance, visit your suppliers, even [something] as simple as that, [then] you are implying that you do all sorts of monitoring on human rights issues and child labor, so you simply cannot say that unless you specify what it is that you are doing and to what extent. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) Appealing to procedure: Structuring judgment using standard audit methodologies The senior partner hierarchy in both firms initially responded to the aforementioned anxieties surrounding the construction of assurance practice by structuring and formalizing practice more coherently to allow judgments to be made within a framework suggesting consistency and cohesiveness. These efforts largely relied on enrolling broad overarching features of financial audit methodologies with an increased focus on documentation of testing. They represented an attempt to make assurance practice more controllable and defendable, particularly from a risk management ⁄ quality control perspective, and to CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1254 Contemporary Accounting Research structure it in a way that linked it closer to traditional audit approaches. For example, more explicit consideration was given to engagement acceptance procedures and the identification of intended users of sustainability reports in order to assist in evaluating reporting completeness. A more detailed client risk analysis was now required, and where clients had not considered clear and acceptable criteria for their sustainability report assurors had to ‘‘seriously consider if it was advisable to give assurance’’ (TD — senior (accountant), 2008). The nature of the interaction that should take place with financial auditors regarding sustainability report content shared with annual financial reports was also explicitly addressed as part of planning procedures. The sharpened focus on risk was partly driven by a desire among managers and partners in both firms to move to provide reasonable assurance opinions on some reported information as opposed to the limited assurance opinions that had predominated in the early evolution of assurance practice. Moreover, in the earlier stages of assurance development risk exposures were not considered significant, as there was a perception among assurors that external stakeholders were not paying significant attention to the quality of reported sustainability information. Much of the initial demand for assurance came from clients concerned with internal as much as external assurance, and assurors initially ‘‘occupied [themselves] with building up the business’’ (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2008) with this constituency. Greater formalization and agreed levels of documentation were gradually introduced in TRU to structure emerging assurance practice, particularly as too much knowledge was perceived as residing in nonaccountant assurors’ heads and could potentially be lost to competitors if staff departed. While feeling powerless to prevent this ‘‘boxing’’ of sustainability assurance in a largely financial audit frame, TRU’s senior associate and manager stressed their initial discomfort with this approach, as they felt expedience was being prioritized in favor of investing in developing more innovative and relevant techniques: I would say [TRU] should think the whole process over from the start, instead of just trying to make quick copies of what is already there. (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2009) The normal [financial] audit approach is used more and more for sustainability assurance. From one perspective this is good. There is about 150 years of thinking supporting it and that is robust. From the other perspective, we need to keep seeing [sustainability assurance] as something innovative, because nonfinancial assurance is still very different. Therefore, you need to be able to let go some things from the past, because it [sustainability assurance] can simply be done better or differently using new techniques and knowledge which often only evolve over time. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2008) Although broad overarching audit steps such as engagement acceptance, planning, risk assessment, and quality review partner sign-off were incorporated into TRU’s framework, it offered limited guidance on the detailed testing required. According to the manager (nonaccountant), senior associate (nonaccountant) and senior (accountant) interviewed, the framework had little substantive impact on the detailed nature of their work. They viewed it as existing mainly to conform to quality control requirements driven by risk management concerns given the increasing number of sustainability assurance assignments TRU was undertaking and the aforementioned desire to provide reasonable levels of assurance, where possible. In effect, the ‘‘gut feel’’ aspects of practice aimed at creating comfort were re-presented within a rational framework drawing on the authority of the generalizable financial audit methodology base (e.g., Power 1999): CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1255 I would not be able to give you even one example of where we have actually changed our assurance approach as a result of now having this methodology. In fact, the methodology, in its first edition, was the [name of client] working program, which we upgraded to be the methodology to be applied to other sustainability assurance engagements. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) It’s not like someone had the idea, right, let’s do nonfinancial assurance, we have to arrange this and that [formally] and after we arrange everything then we will begin. In our case, we just do it, and we have been doing it for five to six years now. However, after a while, especially with the amount of assignments and fees increasing, someone says, ‘‘hey, what’s the story with risk management?’’ and ‘‘hey, how can it be that this engagement letter is not completely the same as the standard one that we send out during the annual [financial] report audit?’’ (TA — senior director (accountant), 2009) For TRU’s nonaccountant manager there was an element of post hoc rationalization of assurance in the requirement to comply rigidly with the new structure: I understand fully that when we are finished, the database should be in order according to all the framework guidance. But, I just really dislike writing things down like that afterwards to make it look like it’s correct, even though in reality it wasn’t done like that at all. By doing that we are fooling ourselves really. (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2009) Within JIF, low levels of documentation also characterized the early emergence of assurance practice. JIF also graduated from a somewhat informal assurance approach where ‘‘the level of organization and documentation was limited with lots of information in people’s heads’’ (JG — manager (nonaccountant), 2006) to a situation where ‘‘the level of formalization has increased’’ (JE — manager (nonaccountant), 2006), consistent with guidance from financial audit methodologies. Managers, seniors, and semi-seniors in JIF (all of whom were nonaccountants) were now more cautious and conscious and were ‘‘covering themselves with documentation’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2009). These assurors, including two of the senior partners interviewed, highlighted, however, that while greater structure was now provided, the key challenges of sustainability assurance remained; they just appeared less problematic within the financial audit-influenced framework. One senior partner in financial audit admitted that this ‘‘structuring’’ merely created an enhanced ‘‘appearance of objectivity’’ (JC — senior partner (accountant), 2008) allowing assurors to present a plausible, defendable overarching process without necessarily providing better guidance on how to tackle core issues like reporting completeness. He expressed concern about JIF’s ability to achieve this key objective: We still have to convince others as to whether we can provide assurance on text, a company story, or on nonfinancial data like CO2 elements and if we have suitable criteria to provide assurance against . . . [but] first, we have to really convince ourselves. (JC — senior partner (accountant), 2008) To summarize, broad-based financial audit frameworks have been adopted by both firms to provide a standardized financial audit–based structure for assurance practice, much of which has evolved in an improvised manner. In TRU in particular, this framework has primarily provided a procedural shell within which assurance practice remains highly judgmental and contingent on particular clients and client-assuror negotiations surrounding engagement scope. Hence, many of the aforementioned assuror concerns about CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1256 Contemporary Accounting Research the ability of available formal practices to adequately achieve core assurance aims, such as assuring on reporting completeness, have remained largely unresolved. In light of these persistent challenges, the final subsection outlines how the hierarchy in both firms has instigated efforts to publicly realign the expectations attached to sustainability assurance as performed by professional accounting firms while simultaneously reinforcing the centrality of their firms’ assurance work within efforts to achieve core aims centered on assessing reporting completeness and relevance. Addressing the limits to auditability: Constructing comfort by enrolling stakeholders as advisors and assurors While many of the assurors displayed a commitment to assessing reporting completeness and relevance, the aforementioned ambiguities and tensions within emerging practice suggested discomfort about their ability to fulfill this aim. In recognition of this uncertainty, the senior partners in the sustainability divisions of both firms have publicly suggested that stakeholders be brought into the assurance process. They argue that assurance on reporting completeness can best be achieved if standard financial audit procedures are used in conjunction with evaluations by external stakeholder groups relevant to reporters. These proposals assign a key part of the responsibility for assessing reporting completeness away from assurors and on to what are termed ‘‘stakeholder panels’’. Both firms, but especially TRU, assert that this will allow them to concentrate on their core competencies in financial audit, focused chiefly on assessing the accuracy and reliability of reported data. JIF has publicly suggested that panels of sustainability report users, complemented with so-called experts if necessary, could initially identify stakeholder information needs and assist assurors in ensuring that reports address all stakeholder relevant information. These panels could, they argue, determine, in consultation with the reporting company, which aspects of a sustainability report they would like to see assured as well as the level of assurance required on selected issues. The proposals eliminate some of the key judgmental or contentious areas from JIF’s assurance process which are central to assessing reporting completeness: Assurance . . . goes further than merely checking that certain figures or claims are true. What really counts . . . is whether or not the report addresses the right topics . . . . The only people who can really determine whether the right issues are addressed and their information needs are satisfied, are the users of the sustainability report themselves . . . . Setting up a stakeholder panel, which formulates its wishes in consultation with the company, is therefore an excellent option for the future. It is even conceivable that this panel — and not the company itself — commissions the assurance provider. (Extract from JIF public report) TRU largely concurs with JIF’s perspective and has advocated for what they term ‘‘dual assurance’’, which also views stakeholder panels as having both advisory and assurance functions, consistent with TRU’s nonaccountant assurors’ view of their roles. TRU maintain that their perspective is motivated by a desire to ensure that ‘‘audit firms’’ do not stray too far from their roots in ‘‘objective facts and audit evidence’’ and further assert that these firms should focus on assessing the reliability of performance data. This involves issuing an opinion on whether companies are reporting things correctly by providing assurance on their materiality processes and performing ‘‘traditional’’ audit work on their reported performance data. Stakeholder panels comprised of diverse stakeholder representatives selected by reporting companies and trained by TRU on the standards used by TRU could advise and assess whether a company is reporting on the relevant issues (reporting completeness). They emphasize the need for ‘‘structural stakeholder panels’’ CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1257 with a ‘‘fixed group of representatives’’ that consult with companies and assurors on a regular basis. These panels would permit positive commentary on sustainability performance which audit firms cannot provide as, according to TRU, they need to ‘‘be objective and independent and stick to the facts’’. This ‘‘connecting’’ of assurors and stakeholder panels will, they claim, ‘‘create efficiency and synergy’’ in assurance processes: Formal assurance providers like audit firms have the skills and the knowledge to provide assurance on the [reliability of] information in the report [by] stating if the company is ‘‘reporting things right’’. The assurance provider can provide input for the stakeholder panel on the information in the report by assuring the information is accurate . . . . He can also provide knowledge and training to the stakeholder panel on the standards used . . . . The stakeholder panel can express an opinion on whether the company is ‘‘reporting the right things’’. (Extract from TRU public report) Both TRU and JIF publicly extol the ability of existing financial audit-based practice to assess performance data objectively while also enrolling the ethical frameworks of the accountancy profession to illustrate their commitment to integrity and independence: An assurance provider that is not bound by professional standards or that is not trained in assurance methodology, may use inferior quality work as a basis for claims that cannot be substantiated . . . . When it comes to a critical assessment by the outside world, this can backfire on the credibility of the company and its report . . . . From this perspective, an accounting firm would be an obvious choice to provide assurance on a sustainability report. [Financial] [a]uditors are, after all, specifically trained to verify information professionally and independently and are also bound by strict quality standards, legislation, and standards. (Extract from JIF public report) Existing assurance practice is not presented as a problem; the problem appears to lie with the largely qualitative, often incomplete data that needs to be assessed to fulfill the core assurance aims extolled by the two firms and other professional bodies. The firms are, however, candid about the practical problems posed by these suggestions. They acknowledge that finding competent and representative members of stakeholder groups willing to sit on stakeholder panels may prove problematic and admit that questions surrounding compensation for stakeholder panel members, their independence, and the criteria to be used to select them also need addressing. The senior partner in TRU was enthused by the prospect of this suggested shift in assurance. He felt it could herald the beginning of an era whereby a new committee in the governance structure of listed companies might become common and provide a key reference point for assurors on the core issue of reporting relevance and completeness: I am very excited about this new form of evaluating sustainability reports. We believe that this will be the future of sustainability reporting and assurance; a cooperation between accountants and stakeholders. The accountant judges the report on the hard facts whereas the stakeholder panels look at the ambition and other emotions in the report . . . . I think that for companies quoted on the stock exchange, a specific secondtier committee within the governance structure that discusses public affairs will become a commodity in the future. They can easily [assess] the relevance of items [reported]. We could work together with them, whereby the committee provides input for the materiality process of the companies, that is, determines what issues to report on, and we [the assurance providers] concentrate on the accuracy of the data. (TE — senior partner (nonaccountant), 2009) CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1258 Contemporary Accounting Research Nonetheless, in common with the senior director (accountant) and senior associate (nonaccountant) in TRU, he recognized the credibility risks in seemingly assuming that stakeholders could perform such a crucial assurance role. He accentuated the need to accord distinct roles to practitioners and stakeholders in the assurance process: An important note to this use of stakeholder panels is that the opinion of the stakeholder panels can often be seen and referred to as an assurance statement, but the scope and depth of their assignment and work performed is different and generally not covered by any standard. So, it is very important to keep these two separated from each other . . . . There might be a risk if statements of stakeholder panels start to be used as assurance. (TA — senior director (accountant), 2009) Attitudes to this shift towards reliance on stakeholder panels were mixed among nonaccountants. One JIF manager, who subsequently moved to a client company’s sustainability division, complained that this potential reversion to data reliability assessments would be ‘‘boring and of no interest’’ to him (JI — manager (nonaccountant), 2006). Another JIF nonaccountant manager moved out of assurance to focus exclusively on a sustainability advisory role in JIF partly due to frustration with the limitations attached to a potentially exclusive focus on the reliability of performance data. Other interviewees were wary of the extent to which stakeholder assessments should actually be relied upon over and above their own ‘‘expert-driven’’ assessments: I recognize that the use of stakeholders in sustainability reporting is of crucial importance. Stakeholders can influence the company and affect what is in the reports. However, they should only provide their opinion and should not try to give assurance as they do with [name of multinational company] because they do not know anything about the measures used and are often much less qualified than we are to make these assessments. It is really difficult to understand how bright people, like the ones in the excellent stakeholder panel that [name of multinational] has, can live with the fact that they express an opinion without having a clue about the actual reliability or relevance of much of the data. I can tell you that when we conducted that engagement we always found material errors, but they find nothing. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) They’ll make presumptions, they’ll look at what’s in the report, and from their own knowledge, what they think should be in the report, but they don’t have the possibility to investigate the company’s internal systems and risk management processes and things like that. (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2010) Stakeholder panels do not know the difference between damage from CO2 and Methane. They don’t have a clue. So accountants do provide a valuable form of assurance where stakeholder panels give their opinion. If certain users do not see the difference between these two then the practice might have high credibility problems. (TC — manager (nonaccountant), 2009) Some interviewees were more positive, with several claiming that given the power of specific stakeholders in certain industries, such as customers, suppliers, responsible investment movements, and NGOs, stakeholders’ direct involvement could help support the assurors’ case when they challenged clients about the completeness of reports. It was also suggested that if formal stakeholder panels and dialogues became ‘‘a continuous part of the governance structure of companies where panels got the opportunity to express their CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1259 opinion in the sustainability report’’ (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009), then assurors could gain more comfort from stakeholders’ assessments of reporting completeness. Hence, the creation of continuously auditable stakeholder engagement processes in companies, a core systems weakness identified by many interviewees, was seen as a possible means of making the proposals work without assurors having to formally enroll stakeholders as part of their assurance process. One nonaccountant even suggested that this form of continuous stakeholder dialogue should be made mandatory: I think it should be in law that if you report on social and environmental issues you must conduct a stakeholder dialogue. Sometimes people just forget the importance of these dialogues, they can serve to greatly increase the legitimacy of both reporting and the assurance undertaken. (TB — senior associate (nonaccountant), 2009) The most recent indications of the impact of these proposals suggest that improved stakeholder engagement and dialogue practices are emerging in ‘‘ambitious multinationals’’ (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2010) in response to assuror encouragement. However, the selection of stakeholders for these panels remains a contentious issue. Moreover, when a lack of completeness is pointed out to companies by stakeholders, feedback mechanisms have not evolved sufficiently to allow stakeholders to evaluate company responses and this is leading to some stakeholder apathy about engaging with companies: I’ve seen a marked increase in the quality of stakeholder engagements. I mean, there were continuous sessions in [name of multinational] last year and also in [name of multinational]. Their whole day of stakeholder sessions comprised small groups and big groups, and was not facilitated by them, but facilitated by [name of sustainability investment NGO]. This was a big change for them actually throwing the doors open. However, there is still some resistance because a consistent problem is that there is not too much clarity about who the stakeholders are. I have one particular client who says, ‘‘I am not going to talk to NGOs’’. But NGOs are a crucial stakeholder for his industry sector . . . . The feedback loop is also not well developed and if feedback is not coming to stakeholders they are not going to bother attending [stakeholder] meetings. (JA — senior manager (nonaccountant), 2010) 7. Discussion and conclusions This paper has sought to develop our understanding of how assurance practitioners have come to construct sustainability assurance practice and how, and the extent to which, these efforts have rendered sustainability reporting auditable. The paper responds to continuing calls for researchers to extend examinations of the back stage of new ‘‘audit’’type practices, particularly those of a discretionary nature (Free et al. 2009) and extends prior work by Gendron et al. 2007, Free et al. 2009 and Radcliffe 1999. The findings are summarized and discussed below in the context of Power’s theoretical insights (1996, 1997, 1999, 2003) on the processes through which new areas are made auditable. The findings demonstrate the fragile nature of attempts to render the domain of sustainability reporting auditable, and highlight the trial and error nature of the processes by which accountants can develop their presence in new markets for their expertise. In particular, they reveal the inherent difficulties involved in directly transferring traditional audit techniques and mindsets to new assurance areas characterized by ambiguous qualitative data and unsupported by (auditable) environments specifically suited to financial audit techniques (e.g., Power 1997; Gendron et al. 2007). Initial assuror attempts to resolve these difficulties and construct comfort regarding their ability to provide assurance on CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1260 Contemporary Accounting Research sustainability reporting content relied extensively on tacit knowledge and ‘‘gut feel’’, which drove highly subjective assessments of certain reported data. Nonaccountant assurors tended to view assurance, and their role within it, as part of an innovative process of instilling change in company practices, thereby benefiting both companies and their stakeholders. While data ambiguity often frustrated them and fueled doubt and anxiety as to whether assurance practice could deliver on aims surrounding reporting completeness, it also energized and challenged them. Emerging, collectively shared feelings of ‘‘comfort’’ (e.g., Pentland 1993) as to what constituted reasonable practice with respect to assessments of materiality and reporting completeness were particularly evident in their criticisms of the purportedly narrow assurance approaches of accountants. Accountants were, however, concerned with the nonaccountants’ change-related ambitions for assurance, especially as they risked compromising assurors’ independence. Assurance practice in both firms has evolved in the presence of vague guidance on required practice. Existing generic ‘‘global’’ standards such as ISAE 3000 were perceived as particularly unhelpful in guiding detailed practices requiring tailoring to different reporting contexts. ISAE 3000 and AA1000AS appear to have acted more to develop broad parameters for nonfinancial data assurance as opposed to providing the detailed guidance on practice that assurors’ desire (see also Wallage 2000). However, while the IAASB’s proposed sustainability assurance standard may address some of the assurors’ concerns, it needs to be mindful of Wallage’s 2000 warning about over-relying on standards to guide practice as ‘‘the relevance of [sustainability-related] issues changes over time [and therefore] externally developed standards may not be suitable for every unique organization’’ (57). Evidence of a spillover effect from financial audit was apparent in the ‘‘surface’’ routines developed for assurors whereby many of the organizational ⁄ procedural aspects of financial audit are now used to establish a sense of due process. These moves to structure practice within methodological ‘‘shells’’ seek to reshape sustainability assurance into a process that lies closer to traditional audit approaches. This was especially evident in TRU where financial audit has had a much more influential role in the development and design of assurance processes. However, while practice has been formalized, according to many interviewees this shift does not seem to have yet had a significant influence on detailed procedures in the field. Hence, while the increased proceduralization facilitates a scripting of sustainability assurance as a rational process, as Power (1995, 1999, 2003) suggests, the highly judgmental, improvised nature of assurors’ practice has persisted. The structural shell, signifying some coherence and competence within assurance practice, potentially makes sustainability assurance more legitimate with and controllable by the hierarchies in both firms (e.g., Carpenter et al., 1994; Curtis and Turley 2007; Gendron and Spira 2009) as well as presenting a clear sign of reasonable practice for external consumption (Power 1996). As Power (2003, 381) asserts, ‘‘[s]tructure is about legitimacy and control, which is not necessarily consistent with better or more efficient auditing’’. The findings reveal the nature of the complexities confronted in sustainability assurance practice when coordinating assorted functional specialities. As Power (1997, 1999) anticipates, the tensions between accountants and nonaccountants over approaches to the gathering and assessment of evidence demonstrate how audit ⁄ assurance ‘‘evidence is not natural, [but] is always relative to the rules of acceptance for particular communities’’ (Power 1999, 69). The working habits and routines of nonaccountants sometimes differed from the relatively rigid habits and routines of financial auditors, leading to some frustration among nonaccountants in particular. This was heightened by the fact that, given the organizational contexts the nonaccountants worked in, financial auditors, especially in TRU, were usually the leaders of assurance work, and therefore assumed authority over the type of work to be completed (e.g., Power 1997). This direction was, however, often CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1261 essential, given many nonaccountants’ initial uncertainty about how to approach data and documentation and their tendency to be less attentive to the need to separate advice and assurance. The findings extend key elements of Radcliffe’s 1999 study of the construction of efficiency auditing. Radcliffe (1999) uncovered how many of the formal elements of audit practice associated with the popular image of auditing as a bureaucratically rational practice were of little importance to auditors in the field (see also Fischer 1996). Consistent with this study, Radcliffe (1999) also found that informal technologies involving ongoing discussion among assurors and tacit knowledge accumulated over time represented some of the key resources mobilized in the (initial) construction of efficiency audit. Radcliffe (1999) also discovered that auditors reacted to and reacted upon their environment as part of their efforts to effect progressive change in auditees. In contrast, the nonaccountants’ ability to introduce and influence ongoing change in auditees in this study was somewhat limited by the independence constraints in JIF and TRU as well as the introduction of increased structure and control over assurance processes. These constraints on nonaccountants were seen as necessary, given the possibility that their personal attachment to ambitious assurance aims could unsettle clients, particularly during negotiations around audit scope. Nevertheless, the need to ‘‘change’’ clients by assisting them to create auditable environments, given initial evidence of inadequate information systems, was a functional necessity if assurance was to develop and expand. The findings challenge Power’s 1999 contention that traditional audit practices are continually reassembled to provide the impression of meeting expectations in new ‘‘audit’’ contexts. In light of the operational difficulties revealed, little reassembling of financial audit practice has occurred, with both firms publicly acknowledging the limitations of traditional audit practice in fulfilling the core aims attached to sustainability assurance. The rhetoric of stakeholder accountability embedded in these aims appears to have been initially adopted without sufficient consideration of the availability of appropriate ‘‘formal’’ technologies (Pentland 2000) or auditable environments, and both firms seem wary of creating an expectations gap with respect to their own assurance efforts. Power (1997, 1999, 2003) anticipates that the perceived ‘‘technical’’ limitations of (and preferences for) financial audit above would lead to an attempt to dilute the aims attached to assurance in such a way ‘‘as to place [them] close to existing [financial audit] competencies’’ (Power 2003, 388). There is evidence that aspects of this process may be in motion in both of the contexts examined. For example, the proposed coupling of external ‘‘expert’’ stakeholder assessments with existing stable, ‘‘objective’’ knowledge derived from institutionally accepted financial audit techniques indicates that the assurance aims for both firms’ work are being narrowed considerably. Consistent with the preferences of the KPMG auditors in Free et al.’s 2009 study of the Financial Times MBA rankings audit, both firms, especially TRU, fall back on their desire to only provide assurance on so-called ‘‘hard’’ performance data (see also Power 1996). TRU’s more assertive views on this more limiting data reliability role for auditors stem from the greater influence of financial audit on the development of sustainability assurance practice in TRU. Core responsibility for delivering on assurance aims surrounding reporting completeness is implicitly assigned outside the ‘‘audit firm’’ to what many individual assurors view as questionable stakeholder ‘‘experts’’ appointed by reporting companies. JIF and particularly TRU accept limited responsibility for any extension of their existing assurance expertise beyond assessing performance data accuracy while simultaneously arguing that their portable set of financial audit practices are an indispensable part of any assurance process aimed at fulfilling the wider aims of reporting completeness and relevance. This ‘‘stable and objective’’ knowledge base attains desired legitimacy in the sustainability assurance domain only when proposed in conjunction with the suggested stakeholder involvement in assurance. As with CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1262 Contemporary Accounting Research accountants’ previous extensions into new audit work domains, the appeal of independence as a defining core competence and professional requirement for accountants is enrolled to bolster the claimed indispensability of the financial audit knowledge base (Power 2003). There could be potential market risks for JIF and TRU attached to the reorientation of expectations and the enrollment of stakeholders discussed above. While the explicit call to use stakeholders to choose the information on which they require assurance ambitiously accords with Elliott’s 2002 perspective on the future of 21st century assurance and with Wallage’s 2000 earlier recognition of the necessity of stakeholder dialogue in assessing the relevance and completeness of sustainability reporting, the use of stakeholder panels to provide explicit assurance on the completeness of reports could unintentionally push accountants back to a limited data-checking role primarily aimed at assessing the accuracy of reported information. This appears to risk undervaluing the contribution these firms are making to the development of assurance practice by clouding the extent of relevant expertise within the firms and the level of assurance their assurors may be capable of delivering. It could also encourage greater scrutiny by sophisticated stakeholders of the ‘‘added value’’ of these firms in this arena (e.g., Delfgauuw 2000, 73–74) in the face of competition from nonaccountant consultancies claiming more relevant expertise (e.g., Owen, Chapple, and Urzola 2009). Moreover, there is a possibility that some dedicated nonaccountant assurors could move to competing nonaccounting consultancies or out of assurance altogether in search of more challenging work. While proposing the enrollment of stakeholders in assurance processes, TRU and JIF need to offer more evidence as to how certain stakeholder groups might possess the expertise to more easily perform assurance (and advisory) tasks, and how competing stakeholder interests can be reconciled. Whether representatives from stakeholder groups such as ‘‘sustainable investors’’, suppliers, local communities, and NGOs would have an interest in this work, and how they would be selected and remunerated, are also issues that require greater consideration. The findings have implications for the nature and extent of reliance users may place on sustainability assurance as they provide insights into the extent to which assurors are grappling with key issues surrounding reporting completeness. They also have potential implications for auditing standard-setters and regulators such as the IAASB, given that they suggest that careful consideration needs to be afforded to whether the aims being espoused for sustainability assurance can be substantively aligned with the operational capabilities available within professional services firms. The evidence in this study indicates that while the two firms studied want to claim the new sustainability assurance space and also engage in some publicly ambitious claims for assurance consistent with those emerging from the accounting profession, their (financial audit) operational capabilities appear to be loosely coupled with some of these aims. Overall, the findings suggest that innovation in new assurance practices in Big Four firms such as TRU and JIF may be stifled by the perceived necessity of relying considerably on financial audit training and techniques and on internal professional firm control procedures which may inadvertently dilute certain forms of expertise that could drive more innovative assurance practices. Gendron and Spira (2009) and some professional accounting bodies (ICAEW 2010b) argue that we remain in crucial need of in-depth qualitative research that provides insights into the back stage of auditing firms in order to improve our understanding of existing and newly emerging audit (and assurance) practice. In light of this study’s findings, this seems especially necessary in new audit arenas into which Big Four professional services firms are entering if we are to better understand how new assurance ⁄ audit practices are being constructed both generally and within these organizational contexts, and the consequences this has for how we interpret the data ⁄ issues on which assurance is provided. It would also be enlightening to study how the nature and perceived limitations of emerging CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1263 sustainability assurance practice may be affecting the interpretation assigned to the concept of ‘‘sustainability’’ by reporting organizations (e.g., Radcliffe 1999 in the context of the concept of ‘‘efficiency’’). Moreover, studies examining the socialization of nonaccountants in Big Four environments could also be a fruitful focus for future study in order to unveil the processes (both formal and informal) through which Big Four firms strive to socialize practitioners performing this form of assurance and the impact these socialization processes may have on practitioners’ professional work, especially the formation of their attitudes and approaches to assessing sustainability-type data. Finally, more focused studies of the operation of controls over the work and decisional discretion of nonaccountants in professional services firm contexts offering new forms of assurance could also develop the insights gained in this study and significantly contribute to our knowledge of the nature of governance within these firms (e.g., Gendron and Spira 2009). References Abbott, A. D. 1988. The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. AccountAbility. 1999. AA1000 Framework: Standard, guidelines and professional qualification. London: AccountAbility. AccountAbility. 2003. AA1000 assurance standard. London: AccountAbility. AccountAbility. 2008. AA1000 assurance standard. Available at http://www.accountability21.net/ uploadedFiles/Resources/Introduction%20to%20the%20revised%20AA1000AS_APS% 202008.pdf, retrieved April 5, 2011. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), and Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). 2010. Evolution of corporate sustainability practices: Perspectives from the UK, US and Canada. London: CIMA. Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), AccountAbility, and KPMG. 2004. The future of sustainability assurance. London: ACCA. Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), AccountAbility, and KPMG. 2009. Assurance-sustainability briefing paper 3: Accountants and sustainability assurance. London: ACCA. Ball, A., D. L. Owen, and R. H. Gray. 2000. External transparency or internal capture? The role of third party statements in adding value to corporate environmental reports. Business Strategy and the Environment 9 (1): 1–23. Barrett, M., D. Cooper, and K. Jamal. 2005. Globalization and the coordinating of work in multinational audits. Accounting, Organizations and Society 19 (1): 1–24. Carpenter, B., M. Dirsmith, and P. Gupta. 1994. Materiality judgements and audit firm culture: Socio-behavioural and political perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society 19 (4–5): 355–80. Carrington, T., and B. Catasus. 2007. Auditing stories about discomfort: Becoming comfortable with comfort theory. European Accounting Review 16 (1): 35–58. Cohen, J., G. Krishnamoorthy, and A. Wright. 2002. Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research 19 (4): 573–93. Cohen, J., G. Krishnamoorthy, and A. Wright. 2010. Corporate governance in the post-SarbanesOxley era: Auditors’ experiences. Contemporary Accounting Research 27 (3): 751–86. Cooper, D. J., and W. Morgan. 2008. Case study research in accounting. Accounting Horizons 22 (2): 159–78. Cooper, D. J., and K. Robson. 2006. Accounting, professions and regulation: Locating the sites of professionalization. Accounting, Organizations and Society 31 (4–5): 415–44. Cooper, S. M., and D. L. Owen. 2007. Corporate social reporting and stakeholder accountability: The missing link. Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (7–8): 649–67. CorporateRegister.com. 2008. Assure view: The CSR assurance statement report. London: CorporateRegister.com. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1264 Contemporary Accounting Research Curtis, E., and S. Turley. 2007. The business risk audit: A longitudinal case study of an audit engagement. Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (45): 439–61. Darnall, N., I. Seol, and J. Sarkis. 2009. Perceived stakeholder influences and organizations’ use of environmental audits. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34 (2): 170–87. Davies, A. B., and S. E. Salterio. 2007. Financial Times business school rankings: A non-traditional assurance case in three parts. Accounting Perspectives 6 (1): 95–113. Delfgauuw, T. 2000. Reporting on sustainable development: A preparer’s view. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 19 (Supplement): 19. 67–74. Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2000. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Handbook of qualitative research, 2nd ed., ed. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 1–28. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Edgely, C. R., M. Jones, and J. Solomon. 2010. Stakeholder inclusivity in social and environmental report assurance. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 23 (4): 532–57. Edmondson, A. C., and S. E. McManus. 2007. Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1155–79. Elliott, R. K. 2002. Twenty-first century audit assurance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 21 (1): 139–46. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE). 2002. Providing assurance on sustainability reports. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE). 2004. FEE call for action: Assurance for sustainability. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE). 2006. Key issues in sustainability assurance: An overview. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE). 2009a. Towards a sustainable economy: The contribution of assurance. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens. 2009b. Multiple stakeholders: The essence of multidisciplinary teams. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fedération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE). 2009c. Sustainability: The contribution of the accountancy profession. Brussels, Belgium: FEE. Fischer, M. J. 1996. Real-izing the benefits of new technologies as a source of audit evidence: An interpretive field study. Accounting, Organizations and Society (2–3): 219–42. Fogarty, T. J., V. S. Radcliffe, and D. R. Campbell. 2006. Accountancy before the fall: The AICPA vision project and related professional enterprises. Accounting, Organizations and Society 31 (1): 1–25. Free, C., S. Salterio, and T. Shearer. 2009. The construction of auditability: MBA rankings and assurance in practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34 (1): 119–40. Gendron, Y. 2009. Discussion of ‘‘The audit committee oversight process’’. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (1): 123–34. Gendron, Y., and M. Barrett. 2004. Professionalization in action: Accountants’ attempt at building a network of support for the WebTrust seal of assurance. Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (3): 563–602. Gendron, Y., D. Cooper, and B. Townley. 2007. The construction of auditing expertise in measuring government performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (1–2): 101–29. Gendron, Y., and L. Spira. 2009. What went wrong? The downfall of Arthur Andersen and the construction of controllability boundaries surrounding financial auditing. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (4): 987–1027. Gendron, Y., and L. Spira. 2010. Identity narratives under threat: A study of former members of Arthur Andersen. Accounting, Organizations and Society 35 (3): 275–300. Gephart, R. P. 2004. Qualitative research and the Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management Journal 47 (4): 454–62. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) The Case of Sustainability Assurance 1265 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). 2006. Sustainability reporting guidelines. Amsterdam: GRI. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). 2008. G3 guidelines. Available at http://www.globalreporting.org/ ReportingFramework/G3Guidelines/, retrieved April 5, 2011. Gray, R. 2010. Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability. . . and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organizations and the planet. Accounting, Organizations and Society 35 (1): 47–62. Hodge, K., N. Subramaniam, and J. Stewart. 2009. Assurance of sustainability reports: Impact on report users’ confidence and perceptions of information credibility. Australian Accounting Review 19 (3): 178–94. Hopwood, A. 2009. Accounting and the environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34 (3–4): 433–39. Humphrey, C. 2008. Auditing research: A review across the disciplinary divide. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 21 (2): 170–203. Humphrey, C., and P. Moizer. 1990. From techniques to ideologies: An alternative perspective on the audit function. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 1 (3): 217–38. Iansen-Rogers, J., and A. Oelschlaegel. 2005. Assurance standards briefing: AA1000 assurance standards and ISAE3000. Amsterdam: AccountAbility and KPMG Sustainability. Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). 2010a. Sustainability assurance: Your choice. London: ICAEW. Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). 2010b. International consistency: Global Challenges Initiative: Providing direction. London: ICAEW. International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). 2007. Proposed strategy for 2009–2011. New York: IFAC. International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). 2011. Sustainability framework 2.0: Professional accountants as integrators. New York: IFAC. Available at http://viewer.zmags.com/publication/ 052263e2#/052263e2/10, retrieved April 5, 2011. International Standard on Assurance Engagements 3000 (ISAE 3000). 2004. Assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information. New York: IFAC. Irvine, H., and M. Gaffikin. 2006. Getting in, getting on, and getting out: Reflections on a qualitative research project. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 19 (1): 115–45. Kolk, A., and P. Perego. 2010. Determinants of the adoption of sustainability assurance statements: An international investigation. Business, Strategy and the Environment 19 (3): 182–98. Knorr Cetina, K. D. 1999. Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. KPMG. 2008. KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2008. Amsterdam: KPMG International Global Sustainability Services. Latour, B 1987. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Mock, T. J., C. Strohm, and K. M. Swartz. 2007. An examination of worldwide assured sustainability reporting. Australian Accounting Review 17 (1): 67–77. Nitkin, D., and L. J. Brooks. 1998. Sustainability auditing and reporting: The Canadian experience. Journal of Business Ethics 17 (13): 1499–507. O’Dwyer, B. 2004. Qualitative data analysis: Exposing a process for transforming a ‘messy’ but ‘attractive’ ‘nuisance’. In A real life guide to accounting research: A behind the scenes view of using qualitative research methods, ed. C. Humphrey and B. Lee, 391–407. Amsterdam: Elsevier. O’Dwyer, B., and D. L. Owen. 2005. Assurance statement practice in environmental, social and sustainability reporting: A critical evaluation. British Accounting Review 37 (2): 205–29. O’Dwyer, B., and D. L. Owen. 2007. Seeking stakeholder-centric sustainability assurance: An examination of recent sustainability assurance practice. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 25: 77–94. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011) 1266 Contemporary Accounting Research O’Dwyer, B., D. L. Owen, and J. Unerman. 2011. Seeking legitimacy for new assurance forms: The case of sustainability assurance. Accounting, Organizations and Society 36 (1): 31–52. Owen, D. L., W. Chapple, and A. Urzola. 2009. Key issues in sustainability assurance: The views of CSR managers and stakeholders’ representatives. London: ACCA. Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Pentland, B. T. 1993. Getting comfortable with the numbers: Auditing and the micro production of macro order. Accounting, Organizations and Society 18 (7–8): 605–20. Pentland, B.T. 2000. Will auditors take over the world? Program, technique and the verification of everything. Accounting, Organizations and Society 25 (3): 307–12. Power, M. 1995. Auditing, expertise and the sociology of technique. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 6 (4): 317–39. Power, M. 1996. Making things auditable. Accounting, Organizations and Society 21 (2–3): 289–315. Power, M. 1997. Expertise and the construction of relevance: Accountants and environmental audit. Accounting, Organizations and Society 22 (2): 123–46. Power, M. 1999. The audit society: Rituals of verification. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Power, M. 2000. The audit society: Second thoughts. International Journal of Auditing 4 (1): 111–19. Power, M. 2003. Auditing and the production of legitimacy. Accounting, Organizations and Society 28 (4): 379–94. Radcliffe, V. S. 1999. Knowing efficiency: The enactment of efficiency in efficiency auditing. Accounting, Organizations and Society 24 (4): 333–62. Radcliffe, V. S. 2010. Discussion of ‘‘The world has changed — Have analytical procedure practices?’’ Contemporary Accounting Research 27 (2): 701–09. Radcliffe, V. S., D. Cooper, and K. Robson. 1994. The management of professional enterprises and regulatory change: British accountancy and the Financial Services Act, 1986. Accounting, Organizations and Society 19 (7): 601–28. Reed, M. I. 1996. Expert power and control in late modernity: An empirical review and theoretical synthesis. Organization Studies 17 (4): 573–97. Royal Dutch Institute for Register Accountants (Royal NIVRA). 2005. Standard for assurance engagements 3410 — Exposure draft: Assurance engagements relating to sustainability reports. Amsterdam: Royal NIVRA. Royal Dutch Institute for Register Accountants (Royal NIVRA). 2007. Assurance engagements relating to sustainability reports, 3410N. Amsterdam: Royal NIVRA. Shafer, W. E., and Y. Gendron. 2005. Analysis of a failed jurisdictional claim: The rhetoric and politics surrounding the AICPA global credential project. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 18 (4): 453–91. Silverman, D 2010. Doing qualitative research. London: Sage. Simnett, R., A. Vanstraelen, and W. F. Chua. 2009. Assurance on sustainability reports: An international comparison. The Accounting Review 84 (3): 937–67. Skaerbaek, P. 2009. Public sector auditor identities in making efficiency auditable: The National Audit Office of Denmark as independent auditor and modernizer. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34 (8): 971–87. Smith, J., R. Haniffa, and J. Fairbrass. 2011. A conceptual framework for investigating ‘capture’ in corporate sustainability reporting assurance. Journal of Business Ethics 99 (3): 425–39. Swift, T., C. Humphrey, and V. Gore. 2000. Great expectations? The dubious financial legacy of financial audits. British Journal of Management 11 (1): 31–45. Trompeter, G., and A. Wright. 2010. The world has changed — Have analytical procedure practices? Contemporary Accounting Research 27 (2): 669–700. Wallage, P. 2000. Assurance on sustainability reporting: An auditor’s view. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 19 (Supplement): 53–65. CAR Vol. 28 No. 4 (Winter 2011)