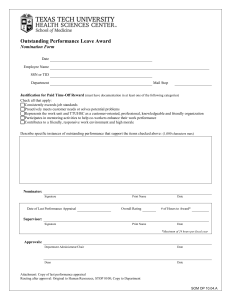

中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 Factors that Influence Customer-Oriented Behavior of Customer-Contact Employees 1 2 Wen-hai Chih Ci-Rong Li 1 Professor, Department of Business Administration, National Dong-Hwa University 2 PhD student, Department of Business Administration, National Dong-Hwa University E-mail: whchih@mail.ndhu.edu.tw Abstract Customer-oriented behavior of customer-contact employees is important during customer decision making process in service industry. In light of research void, this research investigates 520 customer-contact employees across 6 life insurance companies in Taiwan. Empirical data is used to examine the effects of job satisfaction, job involvement and job stress on customer-oriented behavior as well as the moderated effect of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. Significant findings are: (1) job satisfaction and job involvement positively affect customer-oriented behavior; (2) job stress negatively affects customer-oriented behavior; (3) emotional intelligence positively moderates the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. Keywords: customer-contact employee, Customer-oriented behavior, emotional intelligence 摘要 在服務產業中,第一線員工之顧客向導行為在顧客決策過程中是相 當重要的。本研究調查 520 位來自於 6 家台灣壽險公司的第一線員工。 實證工作滿足、工作投入與工作壓力對於顧客導向行為之影響,同時亦 驗證情緒智力在工作壓力與顧客導向行為之間的調節效果。本研究提出 3 項重要發現,包括(1)工作滿足與工作投入均會正向影響顧客導向行為; (2)工作壓力對顧客導向行為則產生反向影響;(3)情緒智力則會正向調節 工作壓力對顧客導向行為之影響。 關鍵字:第一線員工、顧客導向行為、情緒智力 1 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 1. Introduction Since the intangible and interactive characteristics through service delivering process, customer-c ont a c te mpl oy e e s ’be ha vi orpl a y sake yr ol edur i ngc us t ome r s ’ decision making process. In fact, the customer-oriented behavior of customer-contact employees is important for service firms to make long-term profit [2, 37]. In recent years, the number of the companies which invested programs for enhancing customer-oriented behavior of customer-contact employees is growing rapidly [10, 35]. The boundary-spanning nature of service employees often results in some emotional or affective reactions during service delivering [29]. As the result, it is important to study the factors that can influence customer-oriented behavior of customer-contact employees. Previous researches have indicated that emotional or affective responses (e.g., job satisfaction, job stress) of customer-contact employees will influence their customer-oriented behavior [12, 17]. Furthermore, the extent to which employees show the customer-oriented behavior relies on the efforts that customer-contact employees engage in [34]. It is known that job-related factors would influence customer-oriented behavior. In addition, since customer-contact employees are emotional labors, the moderated effect of emotional intelligence is discussed in this research. Thus, in light of this research void, the two questions are examined: First, the test of the effects of job satisfaction, job involvement and job stress on customer-oriented behavior is validated. Second, the moderated effect of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior is further discussed. 2. Literature review and hypotheses In this section we will briefly review the literature concerning customer-oriented behavior. We will then discuss the effects of job satisfaction, job involvement and job stress on customer-oriented behavior as well as the moderated effect of emotional intelligence. 2.1 Customer-oriented behavior Our conceptualization of customer-oriented behavior is consistent with three works. First, Saxe and Weitz [34] suggest that customer-orientation is the degree to which an organization or its employees focus their efforts on understanding and satisfying customers. Second, Stock and Hoyer [41] view customer-oriented behavior as the extent to which service employees use their marketing concepts for helping customers to make purchase decisions as well as satisfying their needs. Third, Brown et al. [3] 2 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 operationalize customer-oriented behavior in terms of a tendency of employees to meet customer needs in job-related environment. Consistent with these views, we define customer-oriented behavior as the extent to which customer-contact employees use their ma r ke t i ngc onc e pt sf ors a t i s f y i ngc us t ome r s ’ne e ds . 2.2 Job satisfaction and its effect on customer-oriented behavior We define job satisfaction as an extent of affective reaction to which customer-contact employees like their jobs [4, 11]. The affect theory of social exchange contends that emotions is a core feature of social exchange process, which individuals engage in to show reciprocal behaviors and support parties from whom they benefit [19]. The application of this theory can range from support among co-workers, information flows among firms as well as the relationships between customer-contact employees and customers [38]. Furthermore it is widely accepted that job satisfaction is a positive emotion [1, 39]. Since customer-contact employees can be benefited for salary or bonus from satisfying customers. According to the affect theory of social exchange, we believe that job satisfaction of customer-contact employees would have a positive effect on customer-oriented behavior. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: H1: Job satisfaction would positively affect customer-oriented behavior. 2.3 Job involvement and its effect on customer-oriented behavior We define job involvement as the extent to which customer-contact employees consider their job to be an essential part of their lives [15, 18]. We argue that job involvement positively affect customer-oriented behavior. Our rationales are as follows: Higher job involvement will lead to higher tendency of workaholic [25], and will be an effective predictor of higher job performance [16]. One might expect that customer-contact employees who have higher job involvement will tend to focus on job-related activities such as thinking of ways to service customers better rather than wasting time on non job-related activities [5, 31]. Thus we believe that higher job involvement would lead to higher customer-oriented behavior. Thus, we proposed H2: Job involvement would positively affect customer-oriented behavior. 2.4 Job stress and its effect on customer-oriented behavior We define job stress is an extent of harmful affective reaction to which service employees do not match the job requirement with their capabilities or resources themselves [22, 26].We expect job stress will negatively affect customer-oriented behavior. It is widely accepted that job environments of customer-contact employees are full of job stress [24], and it follows that job stress will decrease some job outcomes 3 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 performance such as productivity [33]. When job stress takes places, it means there is a poorf i tbe t we e nj obr e qui r e me nta nds e r vi c ee mpl oy e e s ’c a pa bi l i t i e sorr e s our c e s .Si nc e that, one might expect that job stress will deprive customer-contact employees of normal behavioral patterns, thereby in turn negatively affects job-related behavior such as the interactions between customers and themselves [13]. Therefore, we proposed H3: Job stress negatively affects customer-oriented behavior. 2.5 Emotional intelligence and its moderated effect Emotional intelligence can be defined as the abilities concerning the recognition and regulation of emotion in the self and others [23, 40]. We argue that customer-contact e mpl oy e e s ’e mot i ona li nt e l l i g e nc ewoul dmode r a t et her e l a t i ons hi p between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. Specifically, customer-contact e mpl oy e e swhos ee mot i ona li nt e l l i g e nc e sa r ehi g he rt ha not he r s ’woul dha vel i g ht e r negative effect from job stress to customer-oriented behavior. Our rationales are as follows: Emotional intelligence is a psychological mechanism that can prevent individuals from a harmful stress condition [23]. Some evidences revealed that the higher customer-c ont a c te mpl oy e e s ’emotional intelligence, the lower job stress they have [6, 27, 28]. Otherwise, emotional intelligence can be an important adaptive mechanism for helping individuals to adjust the interactions with their environment [28]. Thus, we expect that customer-contact employees with higher emotional intelligence would adjust the harmful affections to a good way, and would eventually diminish the influence from job stress to customer-oriented behavior. H4: Emotional intelligence would positively moderate the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. 3. Research method 3.1 Procedure and participants According to the typology developed by [21], life insurance sales personnel are characterized by the one of high degree of customer-contact employee types. So we chose life insurance sales personnel as the sample in this research, and then selected the top 6 life insurance companies which accounted for approximately 70% market shares in Taiwan. Questionnaires were then mailed to these companies. With the cooperation, life insurance personnel among these companies were asked to fill out the questionnaires with voluntary. Overall, of the 2000 questionnaires distributed, 858 were returned. Of the 858 questionnaires 520 were found to be valid, for a useable response 4 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 rate of 26%. 3.2 Measures All measures were 7-point Likert-t y pes c a l e s ,r a ng i ngf r om “ s t r ong l ydi s a g r e e ” va l uea s“ 1”t o“ s t r ong l ys a gr e e ”va l uea s“ 7” .Ea c hoft heva r i a bl e sus e dt oa c c e s swa s based on the measurement as follows: Customer-oriented behavior. Participants were asked to complete 6 items regarding their customer-oriented behavior. These items which used to access customer-oriented behavior of the extent to which customer-contact employees satisfy c us t ome r s ’ne e dswe r ede ve l ope dba s e don Brown et al. [3]. Job Satisfaction. 6 items from Lichtenstein et al. [20] and Wolniak and Pascarella [42] were the measurement of job satisfaction. Three items were selected from each of their proposed subfacets (i.e., job autonomy and co-worker satisfaction). Job involvement. 6 items evaluating job involvement of participants were adopted from Lassk et al. [18]. The subfacets are time involvement and relationship involvement. Job stress. There were 6 items used to measure job stress of participants. These items were modified from Gellis, Kim and Hwang [8], Joiner [14] and Rothmann, Steyn and Mostert [32]. The subfacets are job demand and lack of support. Emotional intelligence. 12 items from Rahim and Minors [30] and Schutte et al. [36] were used to measure the emotional intelligence of participants. Four items were selected from each of the subfacets (i.e., self-awareness, self-regulation and others-awareness). 4. Results 4.1 Reliability and Validity We examined a 36-item, 5-construct questionnaire in t hi sr e s e a r c h.Cr onba c h’ s alphas for these variables are presented in ta bl e1a ndwe r es a t i s f a c t or y( α> .70). We then conducted factor analysis for convergence validity testing. There are three criterions as follows: First, eigenvalues of factors should be greater than 1. Second, the loadings should be grater than 0.6. Third, the average proportions of variance explained must be greater than 60%. The results are displayed in table 2. It shows that the convergence validities of customer-oriented behavior, job satisfactory, job involvement, job stress and emotional intelligence are satisfactory. For the test of discriminate validity, we conducted two criterions proposed by Gaski and Nevin [7]. First, the correlation coefficient of any two variables must significantly lower than 1. Second, the correlation coefficient of any two variables s houl dl owe rt ha nt heCr onba c h’ sa l pha soft he ms e l ve s .Ther e s ul t sa r es howe di nt a bl e 5 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 1, and the discriminate validities among these were satisfactory. Table 1: Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics Measure 1.COB 2.JSA 3.JIV 4.JSS 5.EI Mean 4.18 3.91 2.61 3.55 3.47 1 .96 2 .72** .94 3 .65** .55** .89 4 -.59** -.50** -.47** .89 5 .46** .35** .36** -.60** .94 Note. Coefficient alpha reliability estimates are presented in bold along the diagonal. Customer-oriented behavior (COB), job satisfaction (JSA), job involvement (JIV), job stress (JSS) and emotional intelligence (EI). *p<0.05, **p<0.001 Table 2: Factor matrix and proportions of variance explained items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Variance explained COB .913 .925 .912 .884 .892 .896 JSA .854 .867 .877 .846 .895 .879 JIV .737 .850 .812 .859 .819 .788 JSS .752 .835 .780 .839 .825 .807 EI .721 .791 .878 .847 .830 .844 .819 .833 .830 .721 .791 .878 81.69% 75.68% 65.89% 65.09% 67.67% 4.2 Hierarchical moderator regression analysis Means and the correlation among variables are shown in table 1. We examined the data for potential systematic differences because of characteristics of life insurance personnel across 6 companies. Across 6 companies, participants were not different in t e r msofge nde r ,χ 2( 5,N=520)=4. 97,p=. 419;a g e ,χ 2( 15,N=520)=19. 85,p=. 178; j obt e nur e ,χ 2( 25,N=520)=33. 60 , p=. 1 17. Given the no significant difference in terms of gender, age and job tenure, we then performed the hierarchical moderator regression analysis to test our hypotheses. It was conducted by entering the dependent variables (job satisfaction, job involvement and job stress) into model 1. The moderated term, created as the multiplication of job stress and emotional intelligence, was then entered into model 2. The results are displayed in Table 3. As we predicted, independent variables influenced customer-oriented behavior (R2= .648, p<0.001). Consistent with hypothesis 1, job satisfaction significant positively affects customer-or i e nt e dbe ha vi or( β=. 499,t=13. 603,p<0. 001) . Anda swe expected, job involvement significant positively influences customer-oriented behavior ( β=. 292,t=8. 995,p <0. 001) .Fur t he r mor e ,j obs t r e s ss i g ni f i c a ntne ga t ively affects 6 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 customer-or i e nt e dbe ha vi or( β=-.228, t = -7.287, p<0.001). Therefore, H1, H2 and H3 were supported. Table 3: Results of hierarchical moderator regression analysis Independent Variables R2 ΔR2 .648 Model 1 (Constant) JSA JIV JSS .655 .007 Model 2 ANOVA F Sig. 316.212 .000 243.916 10.169 B Coefficients Beta t Sig. 2.094 .539 .437 -.328 .449 .292 -.228 7.537 13.603 8.995 -7.287 .000 .000 .000 .000 1.911 .531 .429 -.370 .032 .422 .287 -.258 .086 6.793 13.490 8.883 -7.956 3.189 .000 .000 .000 .000 .002 .000 .002 (Constant) JSA JIV JSS EI*JSS In support of H4, emotional intelligence was found to be a significant moderator between job stress and customer-oriented behavi or( ΔR2= . 0. 007,p<0. 05) .The regression model can be written as COB = .442*JSA + .287*JIV - .258*JSS + .086*EI *J SS.Emot i o na li nt e l l i g e nc e( β= . 086,t= 3. 189,p= 0. 02)pos i t i ve l y moderates the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. H4 was supported. We then conducted the partial differential of COB on JSS. Then the regression mode lc a nbewr i t t e na sδ COB/ δ J SS=-.258 + .86EI. Thus, when emotional intelligence increased, the effect of job stress on customer-oriented behavior was decreased. Furthermore, given the inherent correlation between dependent variables, multicollinearity is tested by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF). It revealed that all VIF were lower than 10 (through 1.09 to 1.60). Multicollinearity, therefore, was not an issue in the preceding analysis [9]. 5. Conclusions 5.1 Discussions and implications Consistent with the affect theory of social exchanges, in this study we found that job satisfaction and job involvement can positively enhance customer-oriented behavior of customer-contact employee; job stress can negatively affect customer-oriented behavior. We also found evidence supporting an adaptive mechanism to explain why some customer contact employees may react more favorable customer-oriented behavior than others. That is, emotional intelligence was a significant moderator of the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. As the emotional intelligence increased, the higher emotional intelligence customer-contact employees 7 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 have the lighter influence of job stress on customer-oriented behavior. Because higher emotional intelligence affords them the ability to adjust their harmful affections (e.g., job stress), and thereby show the better customer-oriented behavior than others. Alternative, this study provides salient implications for service firms for developing customer-oriented behavior programs. More specifically, job satisfaction, job involvement, job stress and emotional intelligence play important role in customer-oriented behavior of service employees. This suggests that service firms can create favorable customer-oriented behavior employees through these variables. From this perspective, a program that can enhance job satisfaction, job involvement, and emotional intelligence as well as can diminish job stress will be a good instrument for service firms. We believe that this study provides meaningful insights into how affective responses affect customer-c ont a c te mpl oy e e s ’be ha vi ora swe l la shows e r vi c ef i r msc a n shape more favorable customer-contact employees. Furthermore, this research represents the first study to investigate the relationship between job involvement and customer-oriented behavior, and we further discuss the moderation effect of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and customer-oriented behavior. We also believe that the results and practices of this study are valuable for service firms to adopt in the future. 5.2 Future research and study limitations There are other important customer-oriented behavior related variables apart from those investigated in our study that warrant future study. For example, personality of customer-contact employees should be investigated to access the effect or moderation effect on customer-oriented behavior. One limitation of this study was the cross-section survey; we suggest future research can conduct a longitude investigation to verify the casual relationship between job related variables and customer-oriented behavior. 1. 2. 3. 4. REFERENCES Bateman, T. S. and Org a n,D. W. ,1983,“ J obs a t i s f a c t i ona ndt heg oods ol di e r :The r e l a t i ons hi pbe t we e na f f e c ta nde mpl oy e ec i t i z e ns hi p, ”Ac a de myofMa na ge me nt Journal, Vol.26, No.4, pp.587-595. Bove ,L.L.a ndJ ohns on,L. W. ,2000,“ Ac us t ome r -service worker relationship model , ”I nt e r na t i ona lJ ou r na lo fSe r vi c eI ndus t r yMa na g e me nt , Vol.11, No.5, pp.491-511. Br won, T.F . ,Mowe n,J .C. ,Dona va n,D. T.a ndLi c a t a ,J . W. ,2002,“ Thec us t ome r orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self-and supervisor performanc er a t i ng s , ”J our na lofMa r ke t i ngRe s e a r c h, Vol.39, No.1, pp.110-119. Bui t e nda c h,J .H.a ndDeWi t t e ,H. ,2005,“ J obI ns e c ur i t y ,e xt r i ns i ca ndi nt r i ns i c 8 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment of maintenance workers i napa r a s t a t a l , ”Sout hAfrican Journal of Business Management, Vol.36, No.2, pp.27-37. Co h e n, A. ,1995,“ Ane xa mi na t i onoft her e l a t i ons hi psbe t we e nwor kc ommi t me nt a ndnonwor kdoma i ns , ”Huma nRe l a t i ons , Vol.48, No.3, pp.239-263. Ga r dne r ,L.J .a ndSt ough,C. , 2003,“ Expl or a t i on of the relationships between wor kpl a c ee mot i ona li nt e l l i g e n c e ,oc c upa t i ona ls t r e s sa nde mpl oy e ehe a l t h, ” Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol.55, 181. Ga s ki ,J .F .a ndNe vi n,J .R. ,1985,“ Thedi f f e r e nt i a le f f e c t sofe xe r c i s e da nd unexercised power sourc e si nama r ke t i ngc ha nne l , ”J our na lofMa r ke t i ngRe s a r c h, Vol.22, No.2, pp.130-142. Ge l l i s ,Z.D. ,Ki m,J .a ndHwa ng ,S.C. ,2004,“ Ne wYor ks t a t ec a s ema na ge r survey: Urban and rural differences in job activities, job stress, and job s a t i s f a c t i on, ”Thej ournal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, Vol.31, No.4, pp.430-440. Hair, J. T., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. and Black, W. C., 1995, Multivariate Data with Readings (4th Ed.), Prentice-Hill, Englewood Cliffs. Hallowell, R., Schlesinger, L. A. andZor ni t s ky ,J . ,1996,“ I nt e r na ls e r vi c equa l i t y , c us t ome ra ndj obs a t i s f a c t i on:l i nka g e sa ndi mpl i c a t i onsf orma na g e me nt , ”Huma n Resource Planning, Vol.19, No.2, pp.20-31. Hi r s c hf e l d,R.R. ,2000,“ Doe sr e vi s i ngt hei nt r i ns i ca nde xt r i ns i cs ubs c a l e soft he Mi n ne s ot as a t i s f a c t i onque s t i o nna i r es hor tf or m ma keadi f f e r e nc e ? ”Educ a t i ona l Psychological Measurement, Vol.60, No.2, pp.255-270. Hof f ma n,D.K.a ndI ngr a m, T.N. ,1991,“ Cr e a t i ngc us t ome r -oriented employees: Thec a s ei nhomehe a l t hc a r e , ”J our na lofHuman Capacity Management, Vol.11, No.2, pp.24-32. J a ma l ,M. ,1990,“ Re l a t i ons hi pofj obs t r e s sa ndt y pe -a behavior to employees' job satisfaction organizational commitment, psychosomatic health problems, and t ur nove rmot i va t i on, ”Huma nRe l a t i ons , Vol.43, No.8, pp.727-738. J oi n e r , T. A. ,2001,“ Thei nf l u e nc eofna t i ona lc ul t ur ea ndor g a ni z a t i ona lc ul t ur e a l i g nme ntonj obs t r e s sa ndpe r f or ma nc e :Evi de nc ef r omGr e e c e , ”J our na lof Managerial Psychology, Vol.16, No.3, pp.229-242. Ka nung o,R.N. ,1982,“ Me a s ur e me ntofj oba ndwor ki nvol ve me nt , ”J our na lof Applied Psychology, Vol.67, No.3, pp.341-349. Ke l l e r ,R. T. ,1997,“ J obi nvol ve me nta ndor g a ni z a t i ona lc ommi t me nta s l ong i t udi na lpr e di c t or sofj obp e r f or ma nc e : As t udyofs c i e nt i s t sa nde ng i ne e r s , ” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol.82, No.4, pp.539-545. 9 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 17. Ke l l e y ,S. W. ,1992,“ De ve l opi ngc us t ome ror i e nt a t i ona mongs e r vi c ee mpl oy e e s , ” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.20, 27-36. 18. Lassk, F. G., Marshall, G. W., Cravens, D. W. and Moncrief, W. C., 2001, “ Sa l e s pe r s onj obi nvol ve me nt : Amode r npe r s pe c t i vea ndane ws c a l e , ”Thej our na l of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Vol.21, No.4, pp.291-302. 19. La wl e r ,E.J . ,2001,“ Ana f f e c tt he or yofs oc i a le xc ha ng e , ”TheAme r i c a nJ our na l of Sociology, Vol.107, No.2, pp.321-353. 20. Li c h t e ns t e i n,R. , Al e xa nde r ,J . A. ,Mc Ca r t hy ,J .F .a ndWe l l s ,R. ,2004,“ St a t us differences in cross-functional teams: Effects on individual member participation, j obs a t i s f a c t i on,a ndi nt e ntt oqui t , ”J our na lofHe a l t ha ndSoc i a lBe ha vi or, Vol.45, No.3, pp.322-335. 21. Love l oc k,C.H. ,1983,“ Cl a s s i f y i ngs e r vi c e st oga i ns t r a t e g i cma r ke t i ngi ns i g ht s , ” Journal of Marketing, Vol.47, No.1, pp.9-20. 22. Lu,J .L. ,2005,“ Pe r c e i ve dj obs t r e s sofwome nwor ke r si ndi ve r s ema nuf a c t ur i ng i ndus t r i e s , ”Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, Vol.15, No.3, pp.275-291. 23. Mayers, J. D. and Salovery, P., 1997, Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications, Basic Books, New York. 24. Mont g ome r y ,D.C.a ndBl odg e t t ,F .G. ,1996,“ Amodel of financial securities s a l e s pe r s ons ' j obs t r e s s , ”J our na lofSe r vi c e sMa r ke t i ng , Vol.10, No.3, pp.21-38. 25. Mudr a c k,P .E.a ndNa ught on, T.J . ,2001,“ Thea s s e s s me ntofwor khol i s ma s behavioral tendencies: scale development and preliminary empirical test i ng, ” International Journal of Stress Management, Vol.8, No.2, pp.93-111. 26. Ne t e me y e r ,R.G. ,Ma xha m,J .G.a ndPul l i g ,C. ,2005,“ Conf l i c t si nt he work-family interface: Links to job stress, customer service employee performance, and customer purchase intent , ”J our na lofMa r ke t i ng , Vol.69, No.2, pp.130-143. 27. Ni kol a ou,L.a ndTa s ous i s ,L. ,2002,“ Emot i ona li nt e l l i g e nc ei nt hewor kpl a c e e xpl or i ngi t se f f e c t sonoc c upa t i ona ls t r e s sa ndor g a ni z a t i ona lc ommi t me nt , ” International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol.10, No.4, pp.327-342. 28. Oginska-Bul i k,N. ,2005,“ Emot i ona li nt e l l i g e nc ei nt hewor kpl a c ee xpl or i ngi t s e f f e c t sonoc c upa t i ona ls t r e s sa ndhe a l t hout c ome si nhuma ns e r vi c ewor ke r s , ” International journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, Vol.18, No.2, pp.167-175. 29. Pa r ki ng t on,J .J .a ndSc h ne i de r ,B. ,1979,“ Somec or r e l a t e sofe xpe r i e nc e dj ob s t r e s s : Abounda r yr ol es t udy , ”Ac a de myofMa na g e me ntJ our na l , Vol.22, No.2, pp.270-281. 30. Ra hi m,M. A.a ndMi nor s ,P . ,2003,“ Ef f e c t sofe mot i ona li ntelligence on concern 10 中華民國品質學會第 42 屆年會暨第 12 屆全國品質管理研討會 31. 32. 33. 34. f orqua l i t ya ndpr obl e ms ol vi n g , ”Ma na g e r i a l Audi t i ngJ our na l , Vol.18, No.2, pp.150-155. Ro s i n,H.a ndKor a bi k,K. ,1995,“ Or ga ni z a t i ona le xpe r i e nc e sa ndpr ope ns i t yt o l e a ve : Amul t i va r i a t ei nve s t i g a t i onofme na ndwome nma na g e r s , ”J ournal of Vocational Behavior, Vol.46, No.1, pp.1-16. Ro t hma nn,S. ,St e y n,L.J .a ndMos t e r t ,K. ,2005,“ J obs t r e s s ,s e ns eofc ohe r e nc e a ndwor kwe l l ne s si na ne l e c t r i c i t ys uppl yor g a ni z a t i on, ”Sout hAf r i c a nJ our na lof Business Management, Vol.36, No.1, pp.55-63. Sa g e r ,J .K. ,1994,“ As t r uc t ur a lmode lde pi c t i ngs a l e s pe opl e ' sj obs t r e s s , ”J our na l of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol.22, No.1, pp.74-84. Sa xe ,R.a ndWe i t z ,B. A. ,198 2 ,“ TheSOCOs c a l e : Ame a s ur eoft hec us t ome r orientationofs a l e s pe opl e , ”J our na lofMa r ke t i ngRe s e a r c h, Vol.19, No.3, pp.343-351. 35. Sc hl e s i ng e r ,L. A.a ndZor ni t s ky ,J . ,1991,“ J obs a t i s f a c t i on,s e r vi c ec a pa bi l i t y ,a nd c us t ome rs a t i s f a c t i on: Ane xa mi na t i onofl i nka g e sa ndma na g e me nti mpl i c a t i ons , ” Human Resource Planning, Vol.14, No.2, pp.141-149. 36. Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Copper, J. T., Golden, C. J .a ndDor nhe i m,L. ,1998,“ De ve l opme nta ndva l i da t i onofame a s ur eof e mo t i ona li nt e l l i g e nc e , ”Pe r s ona l i t ya ndI ndi vi dua lDi f f e r e nces, Vol.25, No.2, pp.167-177. 37. Se r g e a nt , A.a ndFr e nke l ,S. ,2 0 00,“ Whe ndoc us t ome rc ont a c te mpl oy e e ss a t i s f y c us t ome r s ? ”J our na lofSe r vi c eRe s e a r c h, Vol.3, No.1, pp.18-34. 38. Si e r r a ,J .J .a ndMc Qui t t y ,S. , 2 005,“ Se r vi c epr ovi de r sa ndc us t ome r s :Soc i a l exc ha nget he or ya nds e r vi c el oy a l t y , ”J our na lofSe r vi c e sMa r ke t i ng , Vol.19, No.6, pp.392-400. 39. Smi t h,C. A. ,Or ga n,D. W.a n dNe a r ,J .P . ,1983, “ Or g a ni z a t i ona lc i t i z e ns h i p be ha vi or :I t sna t ur ea nda nt e c e de nt s , ”J our na lofAppl i e dPs y c hol ogy , Vol.68, No.4, pp.653-663. 40. Spe c t or ,P .E. ,2005,“ I nt r oduc t i on:Emot i ona li nt e l l i g e nc e , ”J our na lof Organizational Behavior, Vol.26, No.4, pp.409-410. 41. St o c k,R.M.a ndHoy e r , W.D. ,2002,“ Le a de r s hi ps t y l ea sdr i ve rofs a l e s pe opl e ' c us t ome ror i e nt a t i on, ”J our na lofMa r ke t-Focused Management, Vol.5, No.4, pp.355-376. 42. Wol ni a k,G.C.a ndPa s c a r e l l a ,E.T. ,2005,“ Thee f f e c t sofc ol l e g ema j ora ndj ob f i e l dc ongr ue nc eonj obs a t i s f a c t i on, ”J our na lofVoc a t i ona lBe ha vi or , Vol.67, No.2, pp.233-251. 11