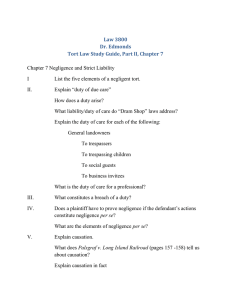

NEGLIGENCE NEGLIGENCE: Conduct which falls below the standard of (reasonable) care established by law for the protection of others against unreasonable risk of harm. To establish a prima facie case for negligence, the following elements must be proved: (1)duty, (2) breach (of duty), (3) causation (in fact & proximate), & (4) damages. “NEGLIGENT BEHAVIOR” (1) DUTY: a legal obligation on the actor to use reasonable or ordinary care for the protection of others against unreasonable risks Question of law (court) (2) BREACH: a failure of the actor to conform to the required standard of care (*liability) Question of fact (jury) – UNLESS judge determines that no reasonable jury could find that a duty was breached under the circumstances (4) DAMAGES: the money awarded for actual loss as a result of a tortious act of another NO NOMINAL DAMAGES “Nuisance” NEGLIGENCE FORMULA (DEGREE OF CARE): 𝑩 < 𝒋(𝑷) × 𝑳 = 𝑫𝑼𝑻𝒀 𝑶𝑭 𝑪𝑨𝑹𝑬 B = Burden of taking adequate precautions (to avoid the risk) P = Probability of Harm L = Severity of Harm RST (3D) § 3: NEGLIGENCE A person acts negligently if he or she does not exercise reasonable care under all the circumstances. In order to determine whether the person’s conduct lacks reasonable care, one must consider: 1) the foreseeable likelihood that the conduct will result in harm 2) the foreseeable severity of the harm 3) the burden of precautions to eliminate or reduce the risk of harm 1 SUMMARY (3) CAUSATION: established by a reasonably close causal connection between conduct & resulting harm (A) CAUSE IN FACT: a necessary cause or any event that leads as a matter of fact to a given result BURDEN (π): show actual causation by a preponderance of the evidence— proof that, more probable than not, the harm was caused by (∆) (B) PROXIMATE (LEGAL) CAUSE: any original event which, in natural unbroken sequence, produces a particular foreseeable result, without which the result would not have occurred (“How far will liability extend?”) 1. DUTY (EXISTENCE OF DUTY) DUTY: An actor ordinarily has a duty to exercise reasonable care when the actor’s own conduct creates a risk of physical or emotional harm to another (RST (3d) § 7) EXCEPTION: when an articulated countervailing principle or policy warrants denying or limiting liability in a particular class of cases, a court may decide that the ∆ has no duty or that the ordinary duty of reasonable care requires modification An actor whose conduct has NOT created a risk of physical or emotional harm to another has NO duty of care to the other unless a court determines that one of the affirmative duties applies SOURCES OF DUTY 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. RULES OF LAW LEGISLATION RELATIONSHIPS PRIVITY OF CONTRACT CUSTOMS & STANDARDS 1. RULES OF LAW provide guidelines for the review of jury determinations of an issue of fact, or fixed rules of law determine that given conduct is or is not negligent as a matter of law 2. LEGISLATION (statutes, ordinances, regulations) often prescribe SOC for the protection of others a. Unexcused violation of a statute is negligence (majority) 3. RELATIONSHIPS (1) Pre-existing relationship between π & ∆ (2) Foreseeability of harm (3) Connection between ∆ and π’s injury, and (4) Reliance by π upon ∆ to protect him a. RESCUE OR AID: NO duty to protect or aid π, even when ∆ realizes π is in a position of danger, UNLESS risk or harm is a result of ∆’s conduct OR there is a pre-existing relationship i. EX: Carrier passenger, innkeeper-guest, landowner-lawful entrant, employer-employee, jailerprisoner, school-student, parent-child, husband-wife, store-customer, & host- guest or friends engaged in a joint social outing b. “GOOD SAMARITAN” statutes in many states relieve physicians & others who render emergency medical aid from all liability for negligence, if it is in good faith c. DUTY TO CONTROL CONDUCT OF ANOTHER: the dominant or custodial member required to use reasonable care to regulate the conduct of the person within his custody or control so as to protect third persons or third persons so as to protect the person in his custody or care i. EX: parent-child, master-servant, permitted user of land/chattel... d. DUTY TO PROTECT SCHOOL CHILDREN: school NOT liable for abuse of teachers because the employee’s acts are outside the scope of employment. i. SCHOOL: may be liable for negligence in hiring, retaining or supervising the abusers. It may also be liable if school officials knew or should have known of the abuse but took no effective action. 1. May also be liable for negligently failing to protect students from violence by other students, or from attacks by intruders on school grounds. ii. STUDENT: may also have a civil rights claim against the school e. PARENT/CHILD i. NO ED recovery for child’s injury as a result of negligence if parent did not witness injury ii. Parents may not maintain a wrongful death action for the death of an unborn child iii. Child may NOT file a “wrongful life” claim to recover damages for diminished childhood 2 f. DOCTOR/PATIENT: arises when a doctor undertakes to render medical services in response to an express or implied request for services by the patient or his guardian i. Not liable for breach of contract unless they guarantee a result ii. INFORMED CONSENT iii. Duty to Disclose: all significant medical info (risks & benefits) that an ordinary physician in the field possesses or reasonably should possess that is material to an intelligent decision by the patient 1. EXCEPTIONS: a. (1) No duty if patient is unconscious & medical treatment is required b. (2) No duty if a patient is so distraught that the doctor reasonably concludes that full disclosure would be detrimental to her well-being c. (3) No duty to inform a patient that you are inexperienced & have never performed the procedure you are doing g. LAWYER/CLIENT: a fiduciary duty arises when a party places confidence/trust in another party with that party’s full knowledge; to be enforceable, must have been created under the law (statutes, legislation, contract) or through factual circumstances i. Act in the best interest of the client ii. Confidentiality/attorney-client privilege STORE OWNER/CUSTOMER (PREMISES LIABILITY) i. Store owner owes a duty to exercise reasonable care in keeping the premises reasonably safe. ii. To establish a premises liability claim, the π must establish that the ∆ had actual or constructive notice of a dangerous condition creating an unreasonable risk of harm and the ∆’s failure to use reasonable care to minimize the harm, which caused the π’s injuries. 1. NO NOTICE required when dangerous condition is continuous and easily foreseeable. h. DUTY TO PROTECT TENANT/GUEST when landlord is in control of property area or responsible for defective condition i. Specific Harm Rule: Under this rule, a landowner does not owe a duty to protect visitors from violent acts of third persons unless he is aware of specific, imminent harm. ii. Prior Similar Incidents Rule: foreseeability is established by evidence of previous crimes on/near premises. iii. Totality of the Circumstances Test: This test takes additional factors into account, such as the nature, condition, and location of the land, and any other relevant factual circumstances. iv. Balancing Test: The foreseeability of harm is balanced against the burden on the business of imposing a duty to protect against the criminal acts of third persons. i. THE TARASOFF RULE: a mental health professional has a duty to use reasonable care to warn a specific third person of a specific serious threat by his patient against that person if the professional, exercising proper professional judgment, in fact predicted or should have predicted that the patient was likely to carry out threat. j. FORESEEABLE π: π in the zone of danger created by the ∆. (RPP-SoC) (Palsgraff v. Long Island Railroad) i. Cardozo View (Zone of Danger) (Majority): the (D) owes the duty of care only to those people who are within the zone of danger (the dangerous area) created by the (D)’s negligent behavior and who suffer foreseeable harm as a result of the (D)’s actions. ii. Andrews View: 4. PRIVITY OF CONTRACT: If π is harmed by breach of contract, special rules determine tort liability. a. ∆ NOT liable where the breach consists merely of his failure to commence performance at all b. ∆ IS liable for tortious mis-performance, whether consisting of acts or omissions to act c. Not Party to Contract, then no cause of action for harm as a result of (D)’s mis performance or nonperformance. i. EXCEPTIONS: NONFEASANCE 1. Public Callings: common carriers, innkeepers, public warehousemen, public utilities, and public officers—are subject to tort liability for nonperformance 3 2. Contracts for Security Services: liable for failure to use reasonable care if the failure increases the risk of harm or the other person relies on the undertaking. 3. Fraud: Promise made without intent to perform may be fraud for which a tort action in deceit will lie. 4. Failure of a telegraph company to transmit a telegram 5. Non-performance by an agent of his contractual duty to supervise property or persons over which he has been given control, or to take certain precautions for the safety of third persons 6. Non-performance of a contract to maintain, inspect, or repair an instrumentality which foreseeably creates a substantial risk of harm to third persons 7. Non-performance by a landlord of his contract to repair the premises ii. EXCEPTIONS: MISFEASANCE 1. Where ∆’s negligence consists of mis-performance after having begun to perform, the privity rule is now obsolete, and majority of courts will subject ∆ to liability. OWNERS & OCCUPIERS OF LAND OUTSIDE THE PREMISES: Possessor must exercise reasonable care to see that activities (conduct) and artificial conditions on the land do not harm his neighbors or passers-by on adjacent ways. NATURAL CONDITIONS: landowner is liable for negligence if he knows, or should have known, that the dangerous natural condition may cause harm, if he did not take reasonable precautions. • Whether it be classified as ‘urban’ or ‘rural,’ landowner may owe a duty of reasonable care as to natural land conditions that threaten outsiders. • R1 § 363 – no liability for injuries resulting from natural conditions of the land other than trees growing near a highway • R2 § 840(2) – urban landowner liable for failure to exercise reasonable care to prevent unreasonable risk of harm to persons using the highway • R3 § 54(b) – duty only if the land is commercial, the landowner knows of the risk or the risk is obvious PUBLIC LAND: the state, city or county owes to all persons coming on the premises a duty to use reasonable care to keep the premises safe. ON THE PREMISES ★ TRESPASSERS: NO duty to exercise reasonable care for a trespasser who enters or remains on land without privilege to do so Immunity from liability to T does NOT extend to intentional torts or harm caused by reckless misconduct. EXCEPTIONS: Frequent Trespassers: duty of reasonable care in the conduct of active operations on the premises and to warn T of dangerous artificial condition on the land which T may not discover, provided the risk to T is one of serious bodily harm. o Anticipated Trespass: duty of reasonable care to those whose trespass can be anticipated. ∆ must know or have reason to know that the place is one where people are likely to trespass Discovered Trespassers: duty of reasonable care to o (1) conduct activities with regard to T’s safety, o (2) warn T of an artificial condition which poses a risk of serious bodily harm, if (D) knows or has reason to know that T is in dangerous proximity to it and that T will probably not discover the danger or realize the risk, and o (3) control those forces within his control which threaten T’s safety or give T an adequate warning of them. 4 DUTY TO RESCUE: duty of reasonable care to come to the aid of a discovered T who is injured or in peril on (D)’s premises, even though (D) is not responsible for T’s situation. CHILDREN: “Attractive Nuisance” Doctrine: A possessor of land is subject to liability for physical harm to trespassing children caused by an artificial condition upon the land if the following requirements are met, and ∆ fails to exercise reasonable care to eliminate the danger to such children or otherwise to protect them. o Duty of reasonable care to children whose trespasses can be anticipated. o ∆ must know or have reason to know that the place where the condition exists is one where children are likely to trespass. ★ LICENSEES: A licensee has a privilege to enter or remain on ∆’s land. (social guest) The owner/occupier has the duty to warn a licensee/social guest of known hidden dangers TAKES THE PROPERTY AS HE FINDS IT DANGEROUS CONDITIONS: ∆ is subject to liability to a licensee if: (a) ∆ knows or has reason to know of the condition and the risk it creates, (b) the licensee does not, (c) ∆ should expect that the licensee will NOT discover or realize the danger, and (d) ∆ fails to exercise reasonable care to make the condition safe, OR to warn the licensee of the condition and the risk involved. SCOPE OF INVITATION: The invitation may be expressly or impliedly limited, as to: (a) duration, (b) purpose, or (c) the portion of the premises to which the invitation extends. If π exceeds the scope of the invitation, he becomes a trespasser, depending upon whether or not ∆ consents to his remaining. ★ INVITEES: An individual who enters another's premises as a result of an express or implied invitation of the owner or occupant for their mutual gain or benefit. ∆ must exercise reasonable care for their safety. ∆ must exercise reasonable care to protect against foreseeable harm by third persons on the premises, and to discover that such acts by third persons are being done or are likely to occur. ∆’s duty does not extend to protection against criminal violence by third persons, but the prevailing view is that in such cases (D)’s negligence is a question of fact for the jury. Public Invitee is a person who is invited to enter or remain on land as a member of the public for a purpose for which the land is held open to the public. “Business Visitor” (RST equivalent of an invitee—same thing) is a person who is invited to enter or remain on (D)’s land for a purpose directly or indirectly connected with business dealings with the possessor of the land. This includes potential or future business. (CL – open to public… exercise reasonable care) Scope of Invitation: The invitation may be expressly or impliedly limited, as to (a) duration, (b) purpose, or (c) the portion of the premises to which the invitation extends. If (P) exceeds the scope of the invitation, he becomes a trespasser, depending upon whether or not (D) consents to his remaining. ★ OTHER PRIVILEGED ENTRANTS: generally classified as licensees. Public Employee, Economic Nexus. Public employees who are required by law regularly to enter (D)’s premises to make inspections, deliveries, or collections necessary to (D)’s operations are invitees. Firemen and Policemen traditionally were classified as licensees. However, there is a trend to make them invitees, at least when upon those parts of the premises held open to the public or when their presence at the place of injury was foreseeable. Firefighter’s Rule or Professional Rescuer’s Rule: In most jurisdictions, the possessor has no general duty of reasonable care to professional emergency responders with respect to negligence that occasioned the emergency response, and in some cases for conditions of the premises. 5 o o limited or abolished in some jurisdictions (Ruiz v. Mero (NJ): officer sued bar) operates to preclude recovery only if the risk created was the type of risk reasonably anticipated by the job. o does not apply if alleged negligence was independent and not related to situation requiring police response Recreational Entrants: most states now have statutes that deny invitee status to persons invited or permitted to come upon (D)’s land without charge for recreational purposes (e.g., hunting, fishing, swimming). ★ LESSOR & LESSEE: lessor of real property is not liable to his lessee or lessee’s guest except when: Latent Hazards: lessor knows or has reason to know of a concealed unreasonably dangerous condition (artificial or natural) existing on the premises at the time the lessee takes possession, but fails to warn the lessee about it, the lessor is subject to liability to the lessee and his guests for physical harm caused by that condition. Pre-existing Conditions: lessor remains liable for a condition (existing at the time the lessee takes possession) which the lessor realizes or should realize unreasonably endangers persons outside the premises. Conditions and Activities During Lease: lessor is subject to liability to persons off the premises if he knows when the lease is executed that the lessee intends to conduct an activity on the premises dangerous to such persons and nevertheless consents to that activity or fails to require proper precautions. Contract to Repair: negligent failure to perform the lessor’s contract to repair the premises subjects him to liability to persons off the premises. Lease for Purpose of Public Admission: lessor must exercise reasonable care to inspect the premises and remedy unreasonably dangerous conditions which exist when possession is transferred Retained Control: lessor is subject to liability for physical harm caused by a dangerous condition located on a part of the premises which the lessee is entitled to use and over which the lessor has retained control, provided the lessor by the exercise of reasonable care could have (1) discovered the condition and the unreasonable risk and (2) made it reasonably safe. Liability extends to the lessee, members of his family, employees, and all lawful visitors on the premises. It does not extend to areas where tenants and their guests are forbidden. Agreement to Repair: In most jurisdictions, the lessor’s contractual promise to repair or maintain the leased premises subjects him to tort liability for negligence in failing to perform his contract resulting in an unreasonable risk of physical harm, whether the disrepair existed before or after the lessee took possession. NOTICE: unless otherwise provided by the lease, the lessor’s duty is only to exercise reasonable care to make the repairs after he has notice of the need for them. No inspection of premises required. Constructive Notice: Where (D) is the owner of premises open to the public, (D) has an affirmative obligation to make reasonably frequent inspections of those premises to make sure that no unsafe condition exists. If (P) can show that the unsafe condition existed for longer than the maximum reasonable interval between inspections, it will be enough for the jury to conclude that (D) was on constructive notice. If the (P) creates the circumstance that gives rise negligence, (D) is not entitled to notice and opportunity to remedy. Services: The lessor may be liable for failure to provide a service required by the lease (e.g. heat, light) where the premises cannot be safely used without it. Negligent Repairs: lessor who undertakes (or purports to undertake) repair of the leased premises is subject to liability for physical harm resulting if (a) he increases the danger which existed before he undertook the repairs, or (b) a concealed danger remains and his repairs create a deceptive appearance of safety, or 6 (c) the danger is a latent one and the lessor assures the lessee that the repairs have been made when in fact they have not, provided the danger (or enhanced danger) is such that the lessee neither knows nor should know that the repairs were not made or were made negligently. 5. CUSTOMS & STANDARDS: When custom and practice have removed certain dangers, the custom may be used as evidence that one has failed to act as is required under the circumstances (NOTICE) (Trimarco v. Klein) ★ EX: Hackbart v. Cincinnati Bengals – general customs of football do not approve the intentional punching or striking of others. STANDARD OF CARE (A) REASONABLE PRUDENT PERSON STANDARD OF CARE: that of the ordinary, reasonable & prudent person (RPP) under the same circumstances (objective test; BPL formula) a) “Ordinary” = not an extraordinarily careful/cautious person who is preoccupied with the idea of potential danger i) to require constant apprehension of danger is beyond “normal” conduct & too harsh a standard b) BURDEN ON π: show that ∆ did not conform to the standard of conduct required (question of fact) 1. REASONABLE MAN: a person exercising those qualities of attention, knowledge, intelligence, & judgment which society requires of its members for the protection of their own interests & the interests of others a. Objective/External Standard: i. Fixed by legislation ii. Adopted from legislation iii. Fixed by judicial decision b. DRIVERS/OWNERS OF VEHICLES: required to know the condition of those parts which are likely to become dangerous where the flaws/faults would be disclosed by a reasonable inspection (Delair v. McAdoo) c. FORGETFULNESS: does NOT excuse negligence, because a reasonable person will not forget what is actually known i. EXCEPTION: when distracted attention, lapse of time, or other similar factors make it reasonable to forget 2. SUPERIOR SKILLS OR KNOWLEDGE: standard of care is that of a RPP of the same skills or knowledge—actor is only expected to exercise those superior qualities in a way that a RPP of same qualities would a. RST (2d) § 289(b), comment m b. RST (3d) § 12 3. CUSTOMS: when custom & practice have removed certain dangers, the custom may be used as evidence that one has fallen below the required standard (Trimarco v. Klein) a. Custom = hat which reflect the judgment, experience, & conduct of any (RST (2d) § 295A, comment a,b) b. PROOF (π): (1) of an accepted/common/customary practice, & (2) evidence the ∆ did NOT conform to it = lack of due care i. LIABILITY = customary practice + evidence ∆ ignored it + ignorance was prox. cause of accident 1. *Does NOT need to be universal—it is sufficient that the custom be fairly well defined & in the same calling or business so that the actor may be charged with knowledge of it or negligent ignorance 2. NOT CONCLUSIVE – just helps prove ii. POLICY: provides opportunities to others to learn of the “safe way” of doing things; guides the common sense of jury to judge a particular conduct under particular circumstances c. JURY decision d. **Customs that are so clearly unreasonable that they are not even to be admitted as evidence of due care?? i. Note 3 (pg. 164) 7 4. 5. 6. 7. ii. ∆ Proofthat in every establishment/situation it has been the practice to ____, it would have no tendency to show that the act was consistent with ordinary care or due regard for safety of those using the premises by their invitation SUDDEN EMERGENCY DOCTRINE: an ordinary person who acts in way that might be considered negligent in response to a sudden emergency/perceived danger, not of his own creation, is not liable for resulting harm so long as the response is reasonably expected under the circumstances of the emergency; π must establish that a jury instruction should be given on the doctrine a. An event qualifies as a sudden emergency if it is: (1) unforeseen, (2) sudden, and (3) unexpected b. EXCEPTION: if the emergency is created by ∆’s negligent conduct, (e.g., puts himself in a position of danger) the doctrine does NOT apply i. Conduct AFTER the emergency has arisen does NOT excuse c. EXCEPTION: where it is physically impossible for ∆ to act volitionally in response to emergency, the doctrine does NOT apply (e.g., when actor suffers some sort of medical crisis) d. EXCEPTION: doctrine NOT appropriate where, in an event of common experience/occurrence, the potential danger presented is one that a person must anticipate & exercise reasonable care to avoid i. RST § 290, comment k PHYSICAL DISABILITIES: a disabled person must take the precautions which the ordinary RPP would take if he had the same disability; conduct is negligent only if it does not conform to that of a RPP with the same disability i. Physical disabilities must be significant & objectively verifiable b. SUDDEN INCAPACITATION: conduct during period of sudden incapacitation or loss of consciousness resulting from physical illness must be reasonably foreseeable to the actor—if not, it may constitute negligence i. Must be reasonable in light of his knowledge of his disability (treated as one of the circumstances under which he acts) c. MENTAL/EMOTIONAL DISABILITY: not considered when determining whether conduct is negligent UNLESS the actor is a child SUPERIOR PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS: (flexible standard) if actor has skills or knowledge that exceed those possessed by most others, they are to be considered in determining whether the actor behaved as a RPP a. No cited cases to distinguish between superior physically & superior knowledge** i. DUTY (∆ disabled): effect of the handicap may be considered in determining whether required standard of care has been met b. LEARNERS/BEGINNERS: generally not considered UNLESS there exists a special relationship between actors that attaches significance to this status i. EX: person learning to drive while teacher is in the car; if an accident occurs that injures the π, the ∆’s status as a beginner is taken into account in negligence determination/liability 1. Status is ignored if the ∆ is sued by a pedestrian injured in the same accident c. INTOXICATION: technically arguable as physical disability, BUT courts consistently refuse to allow it where it is “voluntary” (or even negligent) i. Voluntariness not an excuse to intent—involuntariness only considered if it helps explain the substandard conduct ii. ∆ Obligation? “drunk man entitled to safety as a sober one, & much more in need of it” 1. CHILDREN: standard of what is reasonable to expect of children of like age, intelligence, & experience (majority; RST[2d] §238A; RST[3d] P/E Harm § 10) a. EXCEPTION: more may be required of a child of superior intelligence i. Any mental or emotional disability suffered is considered b. Whether child met the standard = jury decision i. BUT, if only conclusion is that child behaved unreasonably in its estimated capacity, judge may direct verdict against the child c. RULE: children less than 5 years of age are incapable of negligence (RST[3d] § 10(b)) i. MAXIMUM: usually appears to be 17 years old—over 17 the special rule does not apply ii. MINORITY: use of arbitrary age limits to determine capability of negligence d. RULE: special rule for children should NOT be applied when the actor engages in activity which is normally undertaken only by adults, & for which adult qualifications are required (RST[2d]) 8 i. *ADULT STANDARD has been found applicable when child is driving an automobile, motorboat, motorcycle/motor scooter 1. EXCEPTION: adult standard applied to children engaged in dangerous activity that is characteristically undertaken by adults, including the use of firearms (RST[3d] §10(c), comment f) ii. Child standard: has been applied when bicycle riding, deer hunting, building a fire outside, downhill skiing e. **RST [3d] § 11, comment c (physical & mental deficiencies of old age taken into account to determine comparative negligence instruction) 8. INSANITY: no allowance for the mental illness of the defendant--∆ is judged by the standard of a reasonable person, even in the case of “sudden insanity” (majority) a. RST (2d) § 283(B): no allowance is made for lack of intelligence b. RST (3d) § 11(c): no allowance is made for mental or emotional disability 9. STANDARD of π vs. ∆: determination whether RPP standard is met is the same (very few exceptions) (B) PROFESSIONALS (MALPRACTICE) STANDARD OF CARE: that of an ordinary member of the profession with the knowledge, training, & skill (or ability & competence) of a RPP in the profession a) the RPP takes on the profession of the actor, & the objective standard is applied b) NOT an “average” member of the profession—implies ½ of the members could not meet the standard; someone with average skills may still have the degree of skill/care to meet standard 1. CONTRACTS FOR SERVICES: usually, professionals only liable for negligence, because performed service does not have guaranteed result a. Suits are usually in tort for damage caused by negligence i. UNLESS the provider includes an express contract (e.g., a guarantee)—this is enforceable in K law b. No need to contract specifically to exercise ordinary skill of the professional—the law imposes the duty 2. *EXPERT TESTIMONY: required to establish SOC in professional cases bc they are engaged in work that is technical in nature & NOT common knowledge—without expert testimony, a lay person (the jury) is not in a position to understand the nature of the work or the application of the SOC to the type of work a. π must offer expert testimony on the standard of care in order to establish his/her case b. EXCEPTION: expert testimony not required when the negligence is so obvious that it is within the common knowledge & experience of laypersons/jurors (medical) 3. *ATTORNEYS: failing to advocate for or anticipate a substantial change in law requiring an overruling of controlling precedent is illegal malpractice a. The π-client must show that but for attorney’s negligence the client would have been successful in prosecuting or defending the claim b. Most frequent areas of malpractice: real estate, personal injury, family law, estate & probate c. Most common alleged ERRORS: failure to know or properly apply the law, procrastination or failure to follow up, inadequate discovery or investigation, planning error/error in procedure choice, & lost file/document/evidence 4. Generally 3 areas where an professional conduct may be questioned: a. 1) Possession of Knowledge or Skill: e.g., failing to adequately research a topic in a case (which prevented client from receiving benefits they could have received if he had researched) i. Only expected to know what the ordinary member of the profession does—not everything b. 2) Exercise of Best Judgment: the professional is NOT liable for a “mere error of judgment” i. EX: when attorney makes a tactical decision on a debatable point of law; a doctor’s use of discretion in making a diagnosis ii. *Jury instructions must be carefully worded so they are not misled into thinking that professional is not liable as long as she exercised her “best judgment”, even if it was below the SOC 9 c. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Use of Due Care: the professional’s use of due care in the application of the professional’s skill & knowledge i. Steps that are mechanical rather than discretionary—no professional judgment implicated 1. more likely to find liability!!! ii. EX: lawyer failure to file a suit before the running of the statute of limitations; doctor failure to obtain the requisite date on which to exercise trained discretion to develop a diagnosis by, for example, failing to read test results CLERGY: so far, no parishioners’ have succeeded in their attempts to persuade their jurisdiction to recognize clergy malpractice as a separate tort a. Most cases involve allegations that the cleric engaged in consensual sexual relations with an adult parishioner (also mention when a person receiving marriage counseling from cleric) i. Where consent was obtained through intimidation or fraud b. Courts reluctant to recognize a new COA where alleged acts already give rise to an existing COA (e.g., counseling malpractice or battery) or where such a recognition would entangle the court in defining reasonable conduct within the context of religious tenets TEACHERS: courts generally have refused to recognize educational malpractice a. Difficult to determine why the student failed to learn (various educational theories to choose from to set standard) and problems in assigning/awarding money damages) *SPECIALISTS: modified standard for specialists in a particular profession who hold themselves out to have higher skills (than non-specialists in the profession) PRO BONO SERVICES: professionals providing their services pro bono owe the same duty of care as those whose services are compensated OTHER PROFESSIONS: accountants, architects/engineers, designers of group health ins. Plans, doctors/dentists/veterinarians, pharmacists 10 2. BREACH BREACH is a failure to conform to the required standard of care WAYS TO ESTABLISH A BREACH: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Failure to act/warn BPL Formula (unreasonable risk) Negligence per se Res Ipsa Loquitur Customs & Industry Standards ★ FAILURE TO ACT/WARN General Rule, no duty exists to warn or protect another. If unreasonable risk of harm inherent in (D)’s conduct, (D) must reduce that risk so far as reasonably possible; ONLY then will an adequate warning of the remaining risk constitute “reasonable care.” ★ PROOF OF NEGLIGENCE Burden of Proof is on (P) to introduce sufficient evidence to support a finding by a preponderance of the evidence on each element of his cause of action—duty, breach, causation, damages. Whether a duty exists is usually an issue of law for the court; the trier of fact (Jury) determines the other elements. o Evidence Actual/Constructive knowledge of a dangerous condition established through direct/circumstantial evidence, must be proven to impose liability To avoid directed verdict, (P) must provide sufficient evidence to support inference of negligent conduct. ★ UNREASONABLE RISK when the foreseeable probability and gravity of the harm outweigh the burden to (D) of alternative conduct that would have prevented the harm Magnitude of Risk is the probability or likelihood that the harm will result, in conjunction with the gravity or seriousness of the potential harm, are placed on one side of the scale. The gravity of the harm includes both the extent of the damage and the relative societal value of the protected interest. (Risk/Utility) Burden of Alternative Conduct is reducing or eliminating the risk by alternative conduct. Factors relevant in assessing this cost include: (1) the importance or social value of the activity or goal of which (D)’s conduct is a part; BPL Formula (Hand Formula) (2) the utility of the conduct as a means to that end; B < j(P) x L = Duty of Care (3) the feasibility of alternative, safer conduct; (4) the relative cost of safer conduct; B = Burden of taking adequate precautions (5) the relative utility of safer conduct; and P = Probability of Harm (6) the relative safety of alternative conduct. L = Severity of the Harm ★ NEGLIGENCE PER SE: An actor is negligent if, without excuse, the actor (1) violates a statute that is designed to protect against the type of accident the actor’s conduct causes, & if the accident (2) victim is within the class of persons the statute is designed to protect (majority) o (P) is member of class statue sought to protect, and harm is type of harm statute sought to prevent o Violation of statue raises rebuttable presumption of negligence (acceptance discretionary) 11 o (D) must show violation did not cause the harm or provide adequate excuse in circumstances o A violation does NOT per se establish a sufficient causal relation between the violation and injury o Children: A minor’s violation of a statute is only evidence of negligence, not negligence per se. o PERMITTED EXCUSES (a) physical circumstances beyond (D)’s control; (b) innocent ignorance of facts which make the statute applicable; (c) sudden emergencies not of (D)’s making; (d) situations in which it would be more dangerous to comply with the statute than to violate it; (e) reasonable violation in light of (D)’s childhood or physical disability/incapacity; and (f) (D) used reasonable care in attempting to comply with the statute o (P) must prove injuries were directly and proximately caused by the (D)’s violation of the statute ★ RES IPSA LOQUITUR establishes prima facie case of negligence just by mere fact of occurrence. The factfinder may infer that the ∆ has been negligent when the accident causing the π’s harm is a type of accident that ordinarily happens as a result of the negligence of a class of actors of which the ∆ is the relevant member. (Byrne v. Boadle – Barrel) – RULE OF EVIDENCE o (P) has met his burden of production, and is thus entitled to go to the jury o Burden on (D) to rebut presumption of negligence by preponderance of evidence o Injury caused by instrumentality or condition under (D)’s exclusive management or control at time o DOES NOT APPLY when injury may be attributable to multiple causes, some of which not within exclusive control and management of the (D). o BURDEN OF PROOF (π) REQUIREMENTS FOR RIL: To meet the prima facie using res ipsa π must prove: 1. the event is of a kind which ordinarily does not occur in the absence of negligence; 2. other responsible causes, including the conduct of the π and third persons, are sufficiently eliminated by the evidence; and 3. the indicated negligence is within the scope of the ∆'s duty to the (P). 4. There must be no direct evidence of how ∆ behaved in connection with the event. 5. The π must show that the instrument which caused her injury was, at the relevant time, in the exclusive control of the ∆ 12 3. CAUSATION CAUSATION is established by reasonably close causal connection between conduct &resulting harm CAUSE-IN-FACT CAUSE-IN-FACT is a necessary cause or any event that leads as a matter of fact to a given result. π must demonstrate actual causation by a preponderance of the evidence & prove that, more probable than not, the harm was caused by the ∆. CONCURRENT Separate acts of negligence produce a single injury, then each (D) liable for entire result even if acts alone may NOT have caused the result. π may recover from both ∆s even if the π is unable to show which ∆ actually or directly caused the π’s injury. Probable proven reduction in the decedent’s chance for survival is sufficient “General Acceptance” of a scientific technique NOT required in scientific community as an absolute prerequisite to admissibility of expert witness testimony. Dependent Causes: (1) multiple acts or forces combine to cause a single indivisible harm to the (P) harm (2) neither act or force, by itself, would have been sufficient to cause the harm. (3) The but for test is used to determine factual cause. ★ BUT-FOR TEST (sine qua non – essential condition/absolutely necessary): The (D)’s conduct is the factual cause of the π’s injuries if it can be said that without the ∆’s actions the injuries would not have resulted. Applies when there is a single cause that brought about the (P)’s injuries. ▪ Only for 1 ∆ Independent Causes: (1) multiple acts or forces combine to cause a single indivisible harm to the (P) harm (2) each act or force, by itself, would have been sufficient to cause the harm. (3) the substantial factor test is used to determine that each is a material factor in the (P)’s harm. ★ SUBSTANTIAL FACTOR TEST: The substantial factor test is satisfied where four elements are met: ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ (1) multiple forces combine simultaneously to cause the harm (2) any one of these forces is sufficient to cause the harm alone (3) it is impossible to determine which force caused which portion of harm; AND (4) the negligent conduct was a material or significant in causing the harm ∆ is independently liable if a substantial factor in bringing about the (P)’s injury. o Alternative Causes Doctrine: (1) Multiple (D)s are negligent, (2) at least one of the (D)s caused the harm, but (3) the (P) is unable to prove which (D)’s negligence caused the harm. If the (P) satisfies this test, then the burden of proof shifts to each (D) to show that his or her negligence did not cause the injury or be held liable. o Market Share Theory: Where (P) cannot prove which of three or more tortfeasors caused her injury but can show that all were negligent. Each manufacturer is responsible only for a percentage of the (P)’s damages equal to that manufacturer’s share of the market. o Loss-Chance of Survival Doctrine: If a doctor misdiagnoses the patient’s condition, thus delaying treatment, and it can be shown that this delay caused the patient’s chance of survival to be reduced, some courts have found the doctor to be liable even if the patient would have probably died of the condition with proper diagnosis. (P) must show a 51% probability that D’s conduct caused the injury or premature death. (P)’s family may recover damages based only on damages caused directly by premature death, such as loss of earnings or additional medical expenses, etc. Under the preponderance of evidence standard, (P)s fail in their burden of proving factual causation if they do not introduce evidence that proper care would more likely than not have cured or otherwise improved their medical condition PROXIMATE CAUSE 13 PROXIMATE OR LEGAL CAUSE is any original event which in natural unbroken sequence, & without any intervening efficient cause, produces a particular foreseeable result, without which the result would not have occurred. It creates limitations on how far liability will extend. The ∆ is liable only for those harms that are of the same general type or nature as the reasonably foreseeable risk of harm created by the ∆ negligent conduct. Actions must NOT be too remote in time/place. Policy decisions made by the legislature or the courts to deny liability for otherwise actionable conduct are based on considerations of logic, common sense, policy, precedent and justice. o FORESEEABILITY TEST (D) is only liable for the ordinary and natural results of his negligent conduct. (D) is NOT liable for unforeseeable consequences of his negligent conduct. (D) is liable for aggravation of (P)’s pre-existing illness due to the (D)’s negligent conduct. (D) is liable if damage is foreseeable, even though the exact extent of the damages is not foreseeable (D) owes a duty of care only to those (P)s who are in the reasonably foreseeable zone of danger (Palsgraff v. Long Island Railroad) Andrews View (Minority): Work backwards and link the harm to the (D)’s actions you can assign liability to the (D). o EGGSHELL SKULL RULE: It is the general type of harm, not the extent of harm that must be foreseeable. If D’s negligence causes harm to P, (D) is liable for any additional unforeseen physical consequences, provided these do not stem from intervening causes so unlikely that they should supersede D’s liability. If D’s negligence has created or increased the risk that a particular harm to (P) will occur and has been a substantial factor in causing that harm, and the harm is within the scope of risk created by D’s negligent conduct, the precise chain of events giving rise to the harm need not be foreseeable. It is immaterial to the D’s liability that the harm is brought about in a manner, which no one in his position could possibly have been expected to foresee or anticipate. o INTERVENING CAUSES: Are acts, omissions, or other forces that occur after the (D)’s negligent conduct and which contributes to that negligence in producing the (P)’s injury. will NOT necessarily absolve (D) of liability, so long as it was reasonably foreseeable, unless it is a superseding cause. to relieve (D) from liability, such intervening cause must be truly independent of and not set in motion by the original negligence. normal and foreseeable act producing harm to another after the actor’s negligent act or omission causal connection is NOT severed if the intervening act is a normal and foreseeable consequence of the risk created by the (D)’s conduct. (D) is not liable for the intentional intervening malicious acts of third-party which is not reasonably foreseeable ★ Intervening Cause (not superseding) -- FACTORS • Helpless Peril: The first (D) is liable for injuries caused by a second or subsequent (D), where the first (D)’s negligence has foreseeably and unreasonably put the (P) in a position of helplessness or danger to the negligence of others. • Rescuers: where the (D)’s negligence puts the (P) in a position of helpless peril, it is generally foreseeable that the intervening negligence of a rescuer (or would-be rescuer) will exacerbate the (P)’s injuries. • Medical Treatment: Where D’s negligence forces the (P) to seek medical treatment, (D) will be liable for subsequent harm that the (P) might suffer because of medical negligence in treating the initial injury. Exceptions: The fact finder does not consider (P)’s own negligence in creating the condition that (D) was employed to remedy. • Foreseeable Reaction of Others: Harm resulting from other people’s natural and foreseeable responses to dangerous situations created by the (D)’s negligence is not a superseding cause and the (D) is liable for the harm caused by such acts 14 • Suicide: If the (P) becomes so despondent or pained by the injuries he has received from the (D) negligence that he kills himself, and the (P) was sane at the time he committed suicide, the suicide would be a superseding cause, and the (D) has no liability for it. However, the suicide would not regarded as a superseding cause if there was something about the circumstances to indicate that suicide was foreseeable as a normal response to the situation created by D’s negligence. For example, if (P) suffered head injuries that caused mood-altering brain damage, his later suicide might be regarded as a foreseeable, natural consequence of the original negligent driving, and so would not be a superseding cause and (P) would be liable. • Unforeseeable Natural Forces: The extraordinary operation of a force of nature, which merely increases or accelerates harm to another which would otherwise have resulted from D’s negligent conduct, does not prevent (D) from being liable for such harm. ★ SUPERSEDING CAUSE: abnormal, unforeseeable, independent intervening cause that severs liability w/ respect to that first negligent act and is not part of the risk that (D) reasonably foreseeably created by negligence. • Breaks the causal connection between D’s original negligence and (P)’s injuries • If intervening act of D2 is reasonably foreseeable as an ordinary, normal consequence of the (D)'s act or omission (D1)? If yes, than D1’s actions was the proximate cause of (P)’s injury because D2’s actions were not superseding. (D1 one and D2 could be jointly responsible under comparative negligence. There can be more than one proximate cause.) • RESCUE DOCTRINE: if (D) creates a circumstance that places the (P) in danger, then (D) is liable not only for the harm caused to the (P), but also the harm caused to any person injured in an effort to rescue (P). an injured rescuer need not prove the (D) proximately caused his injuries. an injured rescuer need only prove the (D) proximately caused the danger. applies in product liability actions just as it does in negligence actions Cardozo: the heart of this doctrine is the notion that “danger invites rescue.” Rescuer Status Requirements the (D) was negligent to the person rescued and such negligence caused the peril or appearance of peril to the person rescued; the peril or appearance of peril was imminent; an RPP would have concluded such peril or appearance of peril existed; and the rescuer acted with reasonable care in effectuating the rescue. Crimes and Intentional Torts: The (D) is generally not liable for harm caused by a third party’s crime or intentional tort; unless: The (D) had a special obligation to protect the (P) from the third party. Intentional tor or criminal acts are foreseeable and within the scope risk created by D’s negligent conduct. Intervening Force: The (D) is not liable for an intervening force that arises after the reasonably foreseeable risk of harm from the D’s negligent conduct has abated. The foreseeable risk is deemed abated when (P) is put in a position of apparent safety from the foreseeable dangers associated with the D’s negligence or where the dangerous force set in motion by the D’s negligence become apparently safe. ** Public Policy Injury to a mother, resulting in injuries to a later conceived child, does not establish a cause of action against the original tortfeasors. Host is liable for foreseeable negligent acts of intoxicated guest (Public Policy) 15 4. DEFENSES A) PLAINTIFF’S (Π) CONDUCT How to treat the fact that the π’s negligence contributed to the accident? – 3 Basic Options: 1. The law could completely bar π’s claim (contributory negligence) 2. The law could completely ignore π’s culpable conduct (Worker Compensation Acts & No-Fault Automobile Accident Reparation Systems—big advantage to π) 3. The law could adopt one of the first 2 options as a general rule & then set up other rules making exceptions for designated situations (common law for option 1; all-or-nothing approach) 4. The law could compare π’s fault with that of ∆ and reduce π’s damages according to the measure of fault (comparative negligence or comparative fault) (majority) 5. CONSENT (1) CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE is when the law completely bars the π’s claim to recovery if the π’s own negligence was an actual & proximate cause of the injury. This is so regardless of the apportionment of fault between the parties. The π’s 1% fault will absolve the ∆ of 100% of the liability. (minority—4 states); NOT A DEFENSE TO INTENTIONAL TORTS Requires proof of breach of duty (to self), factual cause, & proximate cause RATIONALE: ★ The defense has a penal basis & π is denied recovery as punishment for misconduct ★ π is required to come to court with “clean hands” & the court will not aid one whose own fault has participated in causing his injury ★ A rule of negligence is designed to encourage optimal care by both interacting parties—primary liability may be inadequate where one party acts negligently & the other has an opportunity to avoid the accident POLICY: without the defense of contributory negligence, the injured party may face a diluted incentive to take due care & the system may incur more administrative costs as well ★ Plaintiff’s negligence is an intervening, superseding cause, which makes the ∆’s negligence no longer “proximate”—π’s negligence can be viewed as an act that stops the ∆’s responsibility for the wrongful conduct POLICY: Without the intervention of the π’s action, corrective justice notions would demand that the ∆ rectify the wrong toward the π Should be distinguished from the doctrine of avoidable consequences, which is invoked AFTER the π has been injured ★ Also remember that π’s conduct may be such that it is the sole proximate cause of the injury, even if the ∆ too was negligent Problem: the common law rule of contributory negligence often produced results that a court or jury regarded as unjust—as a result, courts developed ameliorating practices & a group of exceptions for avoiding its application ★ EROSION PRINCIPLE ★ RST § 4: the ∆ has the burden to prove π’s negligence, & may use any of the methods a π may use to prove ∆’s negligence 16 ∆ also has burden to prove that the π’s negligence, if any, was the proximate cause of the π’s damages ★ Courts have been very reluctant to take the contributory negligence issue away from the jury through summary judgment, directed verdict, or judgment as a matter of law Only do so if no reasonable jury could find in favor of the π ★ Plaintiff’s negligence will bar recovery only if it is a substantial factor in bringing about the result ★ Courts have subtly confined the defense by narrowly limiting the scope of proximate cause as applied to RISKS that π exposed himself to by his act of negligence APPLICABILITY OF DEFENSE IN PARTICULAR CIRCUMSTANCES: ★ ∆ ENGAGED IN INTENTIONAL, WANTON OR WILLFUL OR RECKLESS CONDUCT RULE: NOT a defense where ∆ has engaged in “wanton & willful” or reckless conduct because it differs from negligence in both degree and kind ★ STRICT LIABILITY ★ ∆ VIOLATES A STATUTE (NEGLIGENCE PER SE) RULE: Generally, contributory negligence still held to be a defense although ∆ was negligent per se because of violation of a statute EXCEPTION: certain statutes are deemed to abrogate the defense Statutes explicitly abolishing the defense in limited situations (e.g., Federal Employers Liability Act (FELA)) Statutes Intended to Protect a π Unable to Protect Himself o EX: prohibiting child labor, the sale of firearms to minors, the sale of liquor to intoxicated persons, & those requiring safety devices to protect factory workers o Must be determined by the court (RST 2d § 483) EXCEPTIONS: The π may recover in full if: (1) The ∆’s recklessness caused the injury (2) the underlying tort is an intentional tort (3) the last clear chance doctrine applies, or (4) the rescue doctrine applies ∆’S RECKLESSNESS OR GROSS NEGLIGENCE: Contributory negligence not a defense to liability caused by ∆’s reckless or wanton/willful conduct, or gross negligence. LAST CLEAR CHANCE DOCTRINE: if the ∆ had the opportunity to avoid the accident after the opportunity was no longer available to the π, the ∆ is the one who should bear the loss (the whole loss is still placed on one party or the other). ★ Does NOT apply when: ∆’s negligence precedes π’s negligence ∆ is not negligent at all ★ A π who has negligently subjected himself to a risk of harm from the ∆’s subsequent negligence may recover from harm caused thereby if, immediately preceding the harm: π is unable to avoid it by the exercise of reasonable vigilance & car, and The ∆ is negligent in failing to utilize reasonable care & competence and existing opportunity to avoid the harm, when he: (a) knows of the π’s situation & realizes or has reason to realize the peril involved in it, or (b) would discover the situation & have reason to realize the peril, if her were to exercise the vigilance, which then is his duty (discovered peril doctrine): o Conscious LCC: when ∆ discovers π and then acts negligently, π is allowed to recover when ∆ discovers π in a position of peril and can avoid the injury but acts negligently so the injury results 17 o Unconscious LCC: when ∆ negligently fails to discover π in a position of peril, the π is allowed to recover when ∆ should have discovered π but failed to do so because of his own negligence ★ Applications Some jurisdictions have restricted its use to cases where the π was helpless & unable to avoid the danger created by the ∆’s negligence; Others permitted its use if the π was merely inattentive to the danger Some required the ∆ to have discovered that the π was helpless; Others allowed its use if the ∆ should have discovered that the π was helpless RST 2d §§ 479-480, grouping the patterns around the nature of the π’s conduct RESCUE DOCTRINE: where the π negligently injures herself in trying to rescue the ∆ from a predicament that is the result of the ∆’s own negligence, the π will not be charged with contributory negligence unless the π recklessly (or wantonly) injured himself (2) COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE is when the law compares π’s fault with that of the ∆ and reduces π’s damages according to the measure of fault (majority) TYPES OF COMPARITIVE NEGLIGENCE: 1. PURE: the π’s recovery is reduced by the percentage of fault attributable to the plaintiff 2. MODIFIED: a. π “NOT AS GREAT AS” (50% RULE): the π’s recovery is reduced by the percentage of fault attributable to the π as long as the π’s fault is not as great as the ∆’s i. If π’s fault is equal to or greater than the ∆’s, the π is completely barred from recovery b. π “NOT GREATER THAN” (49% RULE): the π’s recovery is reduced by the percentage of fault attributable to the π, as long as the π’s fault is not greater than the fault of the ∆’s i. If π’s fault is greater than the ∆’s, the π is completely barred from recovery c. *NOTE: the 2 modified forms only produce a different result in the 50/50 cases (rule in favor of ∆) i. Important bc a 50/50 case is an appealing on to juries & therefore common d. MULTIPLE ∆’s: majority view is that a π’s negligence should be compared “against all” ∆s together 3. SLIGHT: only in South Dakota—π’s negligence was “slight” in comparison with the ∆ APPORTIONMENT: Some statutes use a special verdict or special interrogatory procedure by which jurors inform the court as to (1) what percentage of fault was attributable to each party & (2) how much damage each claimant suffered BURDEN OF PROOF: the burden is on the ∆ to show both that the π was negligent & that the π’s negligent conduct was the proximate cause of the π’s injuries IMMUNITY? whether or not an immune tortfeasor’s conduct should be considered depends on the type of immunity JOINT & SEVERAL LIABILITY? some states have eliminated J&S liability after adopting comparative negligence, while others have retained it FAILURE TO TAKE ADVANCE PRECAUTIONS AGAINST INJURY & MITIGATION OF DAMAGES AFTER INJURY: BEFORE INJURY: seatbelt use—π negligently fails to wear seatbelt & is more seriously injured than he would have been if he had worn it o Unless there is a statute precluding consideration, such conduct should be taken into account AFTER INJURY: the duty to mitigate damages (doctrine of avoidable consequences) does not allow recovery of those damages that π could have avoided by reasonable conduct on the part of the π after a legal wrong has been committed by the ∆ o The failure to submit to surgery that a reasonable person would undergo to mitigate injury can limit π’s damages for both loss of wages and pain & suffering o The fact that there is some risk involved may not bar the application of the rule 18 (3) ASSUMPTION OF RISK Not favored by the courts & disliked by plaintiff—long history of defeating recovery in cases of genuine hardship (especially in cases involving injuries to employees prior to worker comp acts) 1. EXPRESS: agreement to accept risk of harm arising from ∆’s negligent conduct, π cannot recover for such 2. harm, unless the agreement is invalid as contrary to public policy (1) Whether the risk that injured π fell within the unambiguous terms of the agreement (2) Whether the contract itself violates public policy & therefore should not be enforced Tunkl TEST (public policy factors for transactions): 1. A business of a type generally thought suitable for public regulation 2. The party seeking exculpation is engaged in performing a service of great importance to the public (often a matter of practical necessity for some members of the public) 3. The party holds himself out as willing to perform this service for any member of the public who seeks it, OR at least for any member coming within certain established standards 4. As a result of the essential nature of the service, the party invoking exculpation possesses a decisive advantage of bargaining strength against any member of the public who seeks his services 5. In exercising a superior bargaining power, the party confronts the public with a standardized adhesion contract of exculpation, & makes no provision whereby a purchaser may pay additional reasonable fees & obtain protection against negligence 6. As a result of the transaction, the person or property of the purchaser is placed under the control of the seller, subject to the risk of carelessness by the seller or his agents IMPLIED: π’s implied voluntary consent to encounter a known danger created by ∆’s negligence. ∆ bears burden of pleading, production, & proof. ELEMENTS: (1) Actual knowledge of the particular risk (2) Appreciation of the magnitude of the risk (3) Voluntary encountering of the risk (1) ACTUAL KNOWLEDGE: the best way to show this is through a direct admission from π or someone who overheard him. - Circumstantial evidence may be adequate for the jury to make a reasonable inference - There are certain risks which anyone of adult age must be taken to appreciate: the danger of slipping on ice, of falling through unguarded openings, of lifting heavy objects, etc. (2) SCOPE OF THE RISK ASSUMED: courts place a narrow or specific gloss on “risk” (3) “VOLUNTARY”: the assumption is not voluntary if π is away from home & has to get back, but IS if there is a reasonably short & convenient detour at hand, in good condition - π’s PROTESTS: evidence that he does not consent to assume the risk; BUT, having protested, he may thereafter, even though reluctantly, accept the situation & “waive” the protest (question of fact for the jury) - Often turns on some reasonable alternative to the π’s course A) IMPLIED PRIMARY ASSUMPTION OF RISK: cases where the ∆ owed no duty to the π or where the ∆ did not breach the limited duty owed to the π rather than that π assumed the risks inherent in the activity B) IMPLIED SECONDARY ASSUMPTION OF RISK: cases where the π acts voluntarily but unreasonably to encounter a known risk i) Growing number of courts are in agreement that implied secondary AOR merges with contributory negligence and does not remain a separate defense RST § 3, comment c C) OPEN & OBVIOUS DANGER: eliminated as a bar to recovery; jury should consider any known or obvious characteristics of the danger as factors in the larger comparative negligence analysis (MAJORITY!) ASSUMPTION OF RISK vs. CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE 19 ACTUAL KNOWLEDGE REQUIREMENT: actual, subjective knowledge of the risk is what separates assumption of risk from contributory negligence—if the π merely should have known about the nature & character of the risk through the exercise of reasonable care, then the situation calls for application of contributory negligence UNREASONABLE CONDUCT (π): in order for ∆ to invoke principles of contributory or comparative negligence, the ∆ must show that the π’s failure to protect him was unreasonable under the circumstances. There is no such requirement for assumption of risk—the π may be barred from recovery under assumption of risk principles, even though the π’s conduct was reasonable under the circumstances. B) STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS & REPOSE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS: (procedural) A complete bar to actions that do not meet its time limits—limits the time during which a cause of action can be brought. It is in no way dependent on the merits of the case. In tort, most states impost a 2-3 year time limit. The time limit may vary depending on the (1) basis of liability, (2) general subject matter of claim, & (3) the type of interest invaded. *In most jxns, the SOL is satisfied by the filing of the complaint. SOL is an affirmative defense—if it is not asserted, it is waived. ACCRUAL: most SOL provide that the time within which to file begins to run when the cause of action accrues, which is fixed by the courts • Most courts have held that the SOL begins to run when there has been an actual injury to π’s person or property (time-of-injury rule) Can lead to difficulty in certain types of action for professional malpractice Discovery Rule: SOL begins to run when the π suffers actual damage & discovers the damage was attributable to the professional • Sometimes limited to “foreign objects”—situations where surgeons leave sponges, scalpels, or other objects in patient’s body • Has been extended in many jxns to apply to any action based on a latent injury—the COA accrues only when the claimant in fact knew or reasonably should have known of the alleged wrong(s) o Under this rule, a delayed filing of a complaint is tolerated bc the COA is inherently unknowable o “Should have known”—inquiry notice; SOL starts when person gains sufficient knowledge of facts that would put a reasonable person on notice of the existence of a problem or potential problem such that he would inquire further about it o Dependent on fact-finding by jury makes it unlikely that the ∆ can obtain summary judgment based on SOL • Can be narrow or broad depending on what the π has to discover to trigger the SOL CONTINUING TORT: (professional malpractice cases) some courts have found that the SOL did not begin to run until the course of treatment was complete • LATENT DEFECT: (builders/architects/engineers) affects the application of the SOL—many state legislature shave enacted special SOL dealing with malpractice by builders/architects/engineers If these classes of ∆s are given special protection without any rational basis, the special SOL may be found to be unconstitutional bc it denies equal protection TOLLING: SOL contain provisions that toll (stop) the running of the time within which to file—ordinarily, the tolling stops (SOL starts) when the minor reaches her majority or when the incompetent becomes competent again • EX: minors, legally insane or incompetent, & ∆s who have concealed their identity through fraud or obstructed the filing of the action • Ordinarily, the tolling stops (SOL starts) when the minor reaches her majority or when the incompetent becomes competent again • EQUITABLE TOLLING: (not provided in the statute)—where, for example, the ∆ fraudulently concealed the injury from the π or concealed his own identity Not available if it is someone other then the ∆ that concealed the identity of the ∆ WRONGFUL DEATH ACTIONS: SOL begins to run on the date of death, even if fatal injury occurred earlier Which State’s Law Applies? injury happened in one state but the lawsuit filed in another; the law of the forum determines the SOL 20 • Some states have borrowing rules that provide that the forum’s law applies unless the other jxn’s statute is shorter, in which case that jxn’s limitation is borrowed (prevents states with longer SOL from having to hear lawsuits for claims that arose in other jxns) NOTICE-OF-CLAIM STATUTES: statutes that provide a limited waiver of sovereign immunity to allow tort claims against governmental entities frequently provide that a notice-of-claim must be made to the appropriate govt agency within a particular time frame, in addition to a SOL STATUTE OF REPOSE: limits potential liability by limiting the dime during which a cause of action can arise (substantive). They stem from the equitable concept that a time should arrive when a person is no longer responsible for a past act. Enacted primarily in the area of liability for architects, engineers, & products liability. Special exceptions have been made for particular products, such as asbestos or DES that involve a long latency period between exposure & manifestation of injury. Outside time limit within which the action must commence (sometimes even before a person is injured) “Parts replaced” exception Tolling provisions of the SOL do not apply to the statutes of repose C) IMMUNITIES IMMUNITY vs. PRIVILEGE PRIVILEGE: avoids liability for tortious conduct only under particular circumstances, & because those circumstances make it just & reasonable that the liability should not be imposed IMMUNITY: avoids liability in tort under all circumstances, within the limits of the immunity itself. It is conferred not bc of facts, but bc of the status or position or relationship of the favored defendant. It does not deny the tort, but rather the resulting liability. 1. LITIGATION a. The “absolute privilege” to publish defamation in the course of judicial, legislative, or executive proceedings is an immunity of those engaged in the proceedings, conferred bc of the public interest in protecting them from suit (litigation immunity) b. May protect judges, attorneys, witnesses, court-appointed guardians ad litem, & court-appointed psychiatrists 2. EMPLOYER a. Worker Comp. statutes provide that employees may recover from their employers for work-related injuries without having to show any fault on the part of the employer 3. FAMILIES a. INTERSPOUSAL (Husband/wife): at one point, the general CL rule was that husband & wife were each immune from tort liability to the other spouse for torts committed during coverture. However, the majority of states have no abolished this immunity, & most of the rest have recognized exceptions. i. EXCEPTIONS: 1. Termination of Marriage: after divorce/marital dissolution, spouses are permitted a claim for torts that occurred prior to &, in some jxns, during the marriage (BUT NOT AFTER) 2. Tort Prior to Marriage: some states allow a claim for a tort occurring before a marriage (reasoning: a spouse should not lose a property right bc of entering into a marriage) 3. Intentional Torts: most states allow claims for intentional torts 4. Automobile Accidents: a number of courts have abolished the immunity in these suits 5. Vicarious Liability: most states allow husband or wife to sue one who is vicariously liable for the other spouse’s tort a. EX: husband/wife work for same employer & husband negligently injures the wife in a car accident while on a joint business trip. Wife could sue employer under respondent superior, even though interspousal immunity might bar from suing her husband directly. b. PARENT & CHILD: at CL, a parent & minor child were immune from suit by the other for a personal tort, intentional tort, or negligence 21 i. About 12 states have abolished the doctrine completely. Most states have partially abrogated the doctrine and developed one or more exceptions to the general rule for policy reasons. ii. EXCEPTIONS: 1. Intentional torts (“willful or wanton”)—conduct is so foreign to the relation as to take the case out of it 2. Termination of relationship by death (parent or child) prior to suit; includes wrongful death of child through parental negligence 3. Wrongful death of spouse (child π suing other parent) 4. Legal emancipation of child 5. In loco parentis (stepparent /guardian)—question of fact/jury determination 6. Automobile accidents (relationship is coincidental to the conduct) 7. Negligent Supervision: parents are immune from suit, so long as their conduct in supervising the child is not willful or wanton iii. Majority have abrogated the doctrine in motor vehicle torts—reasoning that the existence of mandatory auto liability insurance renders it unnecessary to bar suit in order to preserve family finances or family harmony 1. Others have said that its existence is a reason to uphold immunity bc it creates an opportunity for fraud & collusion against the insurance company a. Ins. Company receives some protection against this from the “failure to cooperate” clause that appears in the standard liability insurance policy iv. Siblings: generally, NO immunity between siblings v. Minors: (parent sues minor child) most courts have found that immunity, to the extent recognized & including whatever exceptions have been recognized, should be reciprocal vi. Contribution/Indemnity Against Parent: immunity would also protect the parent from actions by other TF’s sued by the child. Many challenges to parental immunity come from claims of joint tortfeasors seeking contribution from PARENTS rather than from children seeking compensation from parents. 1. Court has held that the doctrine precluded product sellers from seeking contribution from parents, but allowed them to present evidence of parents’ conduct to argue comparative negligence, product misuse, & intervening cause vii. Standard of Care (Parents): not required to meet an idealized standard 1. POLICY: parents have always had the right to determine how much independence, supervision, & control a child should have, & to best judge the character & extent of development of their child. The discharge of parental responsibility entails countless matters of personal, private choice, which, in the absence of culpability beyond ordinary negligence, are not subject to review in court. a. Different cultural, educational, & financial conditions affect the manner in which parents supervise their children b. Negligent Supervision: not really allowed as a cause of action—would enable others, ignorant of a case’s peculiar familial distinctions & bereft of any standards, to second-guess a parent’s management of family affairs i. “Day-to-day” exercise of parental discretion, such as having a dog/allowing child to be exposed to the dog, is something the state would rather not disrupt 4. INCOMPETENTS a. One with deficient mental capacity is not immune from tort liability for that reason alone. An incompetent ∆ is held to the same standard as a normal person, particularly in torts involving physical harm. However, ∆’s mental condition may sometimes be relevant in determining whether any tort has been committed. 5. CHARITIES a. The CL tort immunity of charitable, educational, religious, & benevolent organizations no longer exists, except in a few jxns that retain vestiges. b. Legislation has recently began to recreate immunities for particular activities by non-profit charities, or for individuals engaged in certain charitable activities Examples of these exceptions/limitations included: 22 i. Abolishing immunity for charitable hospitals, but retaining it for religious institutions & other charities ii. Implied Waiver: retaining immunity for beneficiaries of the charity—not for π’s who are employees, strangers, or other non-beneficiaries 1. Beneficiary has “impliedly waived” his right to sue in tort by virtue of accepting benevolence iii. Abolishing immunity to the extent that the ∆ is covered by liability insurance OR to the extent that the judgment can be satisfied out of other non-trust fund assets 1. Rationale is that charities hold donations in trust & donor did not give funds with the intent that they be used to pay tort claims 6. GOVERNMENT a. STATE & LOCAL GOVERNMENTS: the doctrine at CL meant that the government could not be sued without its consent, which was also extended to municipal corporations & local entities. Most states have largely abolished their sovereign immunity by comprehensive tort immunity statutes. However, there is LIMITED liability for certain governmental functions. i. State Governments: given firmer limitations in some state statutes & constitutions that required legislative consent for the state to be liable in tort 1. In most states, immunity extends to state agencies & to instrumentalities (perform govt functions) of the state a. EX: prisons, hospitals, educational institutions, state fairs, conservation districts, & public works commissions b. **The legislation creating the agency or instrumentality is examined to determine whether it is included in the immunity i. Entities created after that state has adopted tort claim legislation may specify whether or not they are protected & under what circumstances they can subject the state to liability 2. Most state schemes preserve some special privileges to the state as well as placing various procedural limits on the enforcement of the claims a. Place damages caps on total amount for which it is liable i. Usually upheld even when they represent a small portion of π’s damages b. Create special courts of claims c. Impose additional “notice of claim” requirements 3. Judicial & Legislative Functions: retained immunity even in states that have waived or limited governmental immunity a. Extends to the agents of government (e.g., a legislator may not be sued for how he voted or a judge for how he ruled) b. Almost ALWAYS immune (except when there has been NO state constitutional barrier) ii. Local Govt & Municipal Corporations: (cities, school districts, etc.) have a dual character—on the one hand, they are subdivisions of the state, acting as local governments; on the other, they are corporate bodies, capable of much the same acts & having much the same special interests & relations as private corporations. Immunity is extended to municipal corporations engaged in governmental functions. 1. “Governmental” Functions: administering elections, providing a judicial system, exercising police powers, etc. Those involved in exercising those functions are immune. 2. EXCEPTIONS: a. “Proprietary”/”Private” Functions: courts imposed liability when the city or town engaged in activity that normally was carried out by the private sector of the economy i. Revenue-producing activities such as gas, water, utilities, airports, etc. are generally held to be proprietary functions b. Liability Insurance: when the state has authorized a municipal corporation to purchase liability insurance, a number of courts have held that action to be an implied waiver of immunity to the extent of the insurance 23 iii. State & municipal immunities have been abrogated by legislation, which may be enacted after judicial abrogation 1. Some statutes are modeled on the FTCA, others broadly provide that the state shall be liable to the same extent as any private individual 2. Complex “codes” have been worked out in several states 3. Waivers of Immunity: every state provides for some tort claims against the government under some circumstances a. Standard of conduct to which the entity is held may vary depending on how the claim is characterized i. “Palpably unreasonable” actions iv. DUTY OWED TO CITIZENS: much narrower than duty for private corporations ★ RULE: NO DUTY of police protection (municipalities) to particular members of the public a. EXCEPTION: municipality loses its immunity when a special relationship is created between the police & an individual which gives rise to a special duty i. Situations where the municipality assumes a duty to particular members of the public which it must perform “in a non-negligent manner, although without the voluntary assumption of that duty, none would have otherwise existed” 1. Voluntary assumption of a duty carries with it the obligation to act with reasonable care 2. In doing so, they expose them, without adequate protection, to the risks which then materialize into actual losses 3. Must be an affirmative act(s)/undertaking that creates justifiable reliance ii. EX (special duty): informers, undercover agents, persons under court orders of protection, & school children for whom the municipality has assumed the responsibility of providing crossing guards 1. Many states & the federal government have eliminated immunity for ministerial acts but retained it for discretionary functions b. Discretionary Functions: those where the government is acting to establish policy i. Court review of discretionary decisions would interfere with democratic choices (e.g., how much $ to spend on police force, how many snow plows to buy, whether to build a new school, or provide internet access in public libraries) c. Ministerial Acts: those that implement or effectuate the policies i. Not manifestations of public policy decisions & therefore can subject the government to liability if they are negligently performed 1. EX: govt agent negligently: drives a car, fails to maintain govt premises, or fails to maintain public roads ii. Even if decision is ministerial (no immunity), the claimant till MUST show that there was some special relationship that gave rise to a duty b. THE UNITED STATES: i. Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) (1946): USA waived its tort immunity for $$ damages to person or property “caused by the negligent or wrongful act or omission of any employee of the Government while acting within the scope of his office or employment, under circumstances where the US, if a private person, would be liable to the claimant in accordance with the law of the place where the act or omission occurred” 1. Claimant seeking recovery must present claim to the “appropriate Federal agency” before instituting suit (failure to do so results in dismissal due to lack of SMJ) 2. Time deadlines: a. (1) Claim with the admin. Agency must be filed within 2 years of when the COA accrues (when learns of injury & its cause—not that it was tortious) b. (2) Lawsuit must then be filed within 6 months of when the agency mails the notice of final denial of the claim 24 Lawsuit must be filed in the district where the π resides or where the act/omission occurred Tried by judge (not jury) Attorney fees subject to express regulation USA is NOT liable for interest prior to judgment or for punitive damages ii. EXCEPTIONS: 1. Discretionary Functions: US not liable for acts done with due care in the execution of a statute or regulation (even though invalid), or for an act or omission based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty, whether or not the discretion is abused 2. Specified Torts: US not liable for any claim arising out of assault, battery, false imprisonment, false arrest, malicious prosecution, except in the case of investigative or law enforcement officers; or abuse of process, libel, slander, misrepresentation, deceit, or interference with contract rights. Nor is it subject to strict tort liability in any form. a. Does not apply to medical battery by military or veterans’ benefits health care providers 3. Feres Doctrine: FTCA does not permit recovery for claims arising out of or in the course of activity incident to any active duty service (extended to shield the govt against contribution/indemnity claims brought by product manufacturers sued by service personnel) 4. Officers & Employers: immune when exercising a judicial or legislative function. Highest executive officers are absolutely immune except when acting clearly beyond the bounds of their authority. Lower level executive & administrative employees have a qualified immunity for the good faith exercise of a discretionary function, but are liable for tortious ministerial acts. iii. PUBLIC OFFICERS: may be subject to personal liability for tortious conduct committed in the course of their official duty. Claims against them may be predicated on the CL of torts, special statutes (e.g., Civil Rights Act), or a provision of the Constitution 1. May be shielded from liability if the official’s conduct comes within common law official immunity—a doctrine that is separate & apart from governmental immunity a. May still protect an individual public official, even after govt immunity has been abolished b. When a state has NOT consented to be sued on a matter, a public official may be personally liable if the conduct does not come within the immunity discussed 2. Immunity granted through exclusive remedy provisions—FTCA provides that the remedy against the US for negligent acts of its employees is exclusive of any remedy against the employee a. Individual must be dismissed from the case if the AG or the state equivalent certifies that the govt employee was operating within the scope of his employment at the time of the tortious conduct 3. PO immunity based on a recognition of the need of preserving independence of action, without deterrence or intimidation by the fear of personal liability & vexatious suits (RST 2d § 895(D), comment b) 4. Legislators & judges have absolute immunity for acts committed within scope of their office, even if acted in bad faith a. Some states provide immunity to attorneys appointed to represent indigent criminal ∆s 5. President is absolutely immune for acts within scope of his office a. Presidential aides, like other federal govt officials, are entitled only to a qualified immunity 6. Qualified Immunity: similar in an operative sense to a “privilege,” a. Standard developed with respect to violations of the CRA (1871) b. State official may be deemed to have violated the act if he knew or reasonably should have known that his conduct would violate π’s constitutional rights or if he took the action in bad faith 7. Official immunity is available only with respect to discretionary acts (not ministerial) 3. 4. 5. 6. 25 8. Police: immune unless they undertake a responsibility for protection &/or π justifiably relies on the protection 26 5. DAMAGES DAMAGES constitute the money awarded for actual loss by the tort of another A (D)’s breach of duty must cause the (P) to suffer actual loss or detriment. A (P) may not be able to recover, in negligence, for all types of harm in all cases. Five cardinal elements of damages; past physical and mental pain; future physical and mental pain; future medical expenses; loss of earning capacity and permanent disability and disfigurement. (Nominal damages may not be awarded.) COMPENSATORY DAMAGES (actual damages) are designed to provide restitution for the harm caused to the innocent party. The intent is to return the innocent party, as close as possible, to the position he was in before he was injured by someone’s negligence. These are negligence damages connected to and the apparent result of the injury, or they may simply be implied by the law. Awarded for both pecuniary and non-pecuniary losses. o o o Special Damages allow a person to recover the out-of-pocket expenses he incurred as a result of his injury. These damages include past and future medical bills and lost wages. General Damages include the repair or replacement of any property damaged by the negligent party, pain and suffering, and emotional distress; fundamentally non-economic. Personal Injuries: Victims under tort law can be compensated for Medical expenses Lost wages, or impaired earning capacity Other incidence economic consequences caused by the injury and Pain and suffering A trial court may review a jury’s award of damages to determine if it exceeds the maximum amount which the jury o could reasonably award. An award of damages will be deemed excessive if it falls outside the range of fair and reasonable compensation or results from passion or prejudice, or if it is so large that it shocks the judicial conscience. Property: Awarded for permanent deprivation or destruction of property are generally measured by the market value of the proper at the time of the tort. If real or personal property is damaged but not destroyed, courts generally compensate the victim for the diminished market value of the property but sometimes aware the cost of repairs instead of diminished value. o o Mitigation or the Doctrine of Avoidable Consequences: injured victims have a responsibility to act reasonably to limit or mitigate losses incurred if a (P) fails to act reasonably to mitigate injuries, the (D) will not be held liable for incremental losses that may have been avoided. Collateral Source Rule: Under traditional common law doctrine, the (P)’s recovery against the (D) is not affected by compensation the (P) received for the loss form other sources such as insurance. Such collateral sources for recovery are not disclosed to the jury under the collateral source rule. Numerous reform statutes most notably I the context of medical malpractice, now reject the collateral source rule and allow the jury to consider such insurance payouts and deduct them from the d’s liability. Gratuitous or Discounted medical services are a collateral source not to be considered in assessing the damages due a personal-injury (P). PUNITIVE DAMAGES (exemplary damages… typically not awarded unless gross or negligent) o awarded if the negligent party’s conduct was reckless, wanton, or malicious in nature o expresses moral condemnation of the negligent party o quasi-criminal in nature and serve to deter and punish wrongful activity. 27 o court must weigh the reprehensibility of the (D)’s conduct, the disparity between the actual harm caused and the amount of the punitive damages awarded, and the difference between the punitive damages awarded and the civil penalties imposed under state law. JOINT TORTFEASORS: Parties jointly involved in illegal activity are jointly liable for injuries to a third person regardless of which party directly inflicted the injury or damage upon the third person. o Comparative Negligence: If the injured party is also at fault, negligence damages may be reduced proportionately a concurrent tortfeasor is not jointly and severally liable for the entire amount of the (P)’s judgment does not eliminate joint and several liability o CONTRIBUTION Joint liability is required before any contribution can be ordered. The right to contribution does not exist only between tortfeasors against whom the (P) has obtained judgment. INDEMNITY A joint tortfeasor is not entitled to indemnification from a fellow tortfeasor. If applicable, requires one tortfeasor to fully reimburse another tortfeasor who has paid the Ps judgment regardless of comparative negligence May be required by contract (ex. retailer v manufacturer) o APPORTIONMENT (D) cannot be held liable for a (P)’s subsequent injury where the (P) cannot apportion the damages between the causes of the injuries. o One Satisfaction: if (P) suffers indivisible harm by several parties, (P) is entitled to only one satisfaction. o Mary Carter Agreements where a settling (D) has a stake in the outcome of a case against co-(D)s, are violative of public policy. Pure Economic Loss (P) cannot recover in negligence for economic loss that (P) sustained from physical harm to another or to property in which (P) has no interest. P may not recover for economic loss caused by reliance on a negligent misrepresentation not made directly to (P) or specifically on (P)’s behalf. Exceptions: privity or some “special relationship” between (P) and D Negligent Performance of a Service: client who foreseeably relied on service or other intended beneficiaries. Exercise of Public Right: (P) whose business is based on the exercise of a public right has been allowed to recover for economic loss caused by (D)’s negligent interference with that right. Loss of Consortium an action for tortiously caused injury (negligence, battery, anything) other than death that adversely affects the relationship of husband and wife. Pecuniary damages. When the person whose consortium is lost dies from the tortious conduct, the family members may sue only under wrongful death actions for their loss in quality of life. Wrongful Death allows the survivors of the decedent to recover for their own loss as a result of the death of the victim. Doesn’t allow recovery for their emotional harm that occurred when confronted with the death. 28