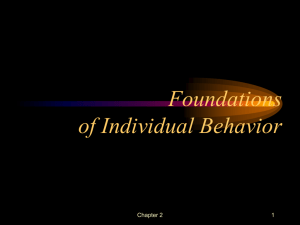

The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2015 Vol. 26, No. 6, 875–903, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.991344 Organizational diversity programs across cultures: effects on absenteeism, turnover, performance and innovation Hilla Peretza*, Ariel Levib and Yitzhak Friedc† a Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Ort Braude College, Karmiel, Israel; School of Business Administration, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA; cWhitman School of Management, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA b This study examined data from over 5000 organizations in 22 countries to address three complementary issues: (1) the influence of national culture on the adoption of diversity programs aimed at recruiting, training and promoting individuals from specific target groups; (2) the moderating effect of national cultural practices on the relationship between these diversity programs and the organizational outcomes of absenteeism and turnover; and (3) the mediating effect of absenteeism and turnover on the relationship between diversity programs and organizational performance and innovation. National cultural values and practices were taken from the GLOBE study and assigned respectively to the organizations in our sample. A multilevel path analysis supported the hypothesized effects of national cultural values on organizational diversity programs. Moreover, cultural practices were found to moderate the relationship between diversity programs and absenteeism and turnover. Our hypotheses on the role of absenteeism and turnover as mediators of the relationship between diversity programs and organizational performance and innovation were also supported. Our findings may help guide managers’ decisions on the adoption of diversity programs in units operating in different national cultures. We discuss the implications of our findings for scholars and practitioners concerned with diversity management issues in a global context. Keywords: absenteeism; diversity programs; GLOBE dimensions; international HRM; national culture; turnover Over recent decades, scholars have shown increasing interest in the characteristics and effects of workforce diversity across the globe (e.g. Ferdman & Sagiv, 2012; Jackson & Joshi, 2011; Kim, 1999; McMahon, 2010; Shen, Chanda, D’Netto, & Monga, 2009; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Workforce diversity is the degree to which the organizational workforce consists of people with different background characteristics. Diversity programs refer to the programs organizations adopt to enhance and maintain workforce diversity. This growing attention to organizational diversity and diversity programs has resulted from the expansion of the global economy across national boundaries, and the growth in workforce diversity related to characteristics such as ethnicity, race, gender, age and disability (e.g. Ferdman & Sagiv, 2012). The increased focus on diversity has been associated with organizational efforts to recruit and maintain through training and promotion a diverse workforce in the USA (Kalev, Dobbin, & Kelly, 2006; Levi & Fried, 2008) and other nations across the globe (e.g. Combs, Nadkarni, & Combs, 2005). While research on workforce diversity is rich and extensive, there are two key questions for which information is lacking in this area. One question is under what *Corresponding author. Email: hillap@braude.ac.il † Current address: Rawls College of Business, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA. q 2015 Taylor & Francis 876 H. Peretz et al. conditions organizations are more likely to adopt diversity programs to enhance workforce diversity. The second question is under what conditions workforce diversity programs will be positively versus negatively related to organizational outcomes such as absenteeism, turnover, performance and innovation. This is an important question because the research has yielded mixed results on the effects of diversity on performance (e.g. cf. Chua, 2013; Cunningham & Sagas, 2004; Ely, 2004; Kochan et al., 2003; Lynch, 2002, 2005; McMahon, 2010; cf. Sowell, 2004). A major contribution of our study is that we address these questions from a global perspective. Most research on diversity has been based in the USA and other Anglophone countries (England, Canada, Australia), leading to a focus on the diversity dimensions, programs and practices that are characteristic of the USA. Furthermore, the cultural and institutional contexts of the research settings have typically been limited to those common within the USA. As Jonsen, Maznevski and Schneider (2011) have noted, there has been a relative neglect of how national values might affect the acceptance and implementation of diversity management efforts in non-US contexts. Jonsen et al. (2011) suggested how different values across societies may influence, how diversity is defined and how diversity management programs are justified and implemented. They also presented examples of how different national values and assumptions regarding ethnic differences and multiculturalism affected the extent and type of diversity management practices in these nations. For example, within several European countries, the widespread view that immigrants and ethnic minorities are outsiders who cannot be assimilated into the national ‘stock’ has prevented or slowed the adoption of diversity programs. Nevertheless, the steady increase in ethnic diversity in most European countries has led both to debates about multiculturalism and to organizational attempts to address the challenges posed by ethnic and cultural diversity (Combs et al., 2005; Ferdman & Sagiv, 2012). Because the ways in which countries and organizations within them address diversity will be affected by the prevailing values in these countries, Jonsen et al. (2011) suggested that researchers take a less US-centric perspective in assumptions about and research in diversity. The major way we do this is by taking into account value dimensions along which the similarities and differences across nations can be assessed. We focus on national cultural values (i.e. the aspirational, ‘should be’ cultural values in the society) as antecedents of organizational adoption of workforce diversity programs, and national cultural practices (i.e. the current ‘as is’ practices prevailing in the society) as moderators of the relationship between workforce diversity programs and organizational outcomes (e.g. absenteeism, turnover, performance and innovation). While national cultural values have been shown to affect human resource practices such as selection, training and performance appraisal (e.g. Aycan, 2005; Aycan et al., 2000; Mendonca & Kanungo, 1994; Peretz & Fried, 2012; Ryan, McFarland, Baron, & Page, 1999), there is little research on the effect of such national cultural values and national cultural practices on workforce diversity programs. We focus on seven national cultural values and practices: individualism/collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, future orientation, gender egalitarianism, humane orientation and performance orientation. These values and practices have theoretical relevance to organizational diversity programs and organizational outcomes, as discussed below. Here we focus on organizational programs aimed at increasing workforce diversity in such categories as race, gender, age and disability by means of the human resource practices of recruitment, training and career progression. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 877 Theoretical background National cultural values and diversity programs Values at the national level are the means by which behaviors and beliefs of members of the larger society can be coherently interpreted. Researchers have made several attempts to define and classify national values (e.g. Aycan et al., 2000; Aycan, Sinha, & Kanungo, 1999; Hofstede, 1991; Hofstede & Peterson, 2000; House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004; House, Javidan, Hanges, & Dorfman, 2002; Javidan, House, Dorfman, Hanges, & Sully de Luque, 2006; Schwartz, 1999). There is general agreement that cultural values are typically shared by members of society, are passed from older to younger members and shape a collective perception of the world (Hofstede, 1991). Researchers have proposed that national cultural values are associated with organizational practices (Aycan, 2005; Fischer, Ferreira, Assmar, Redford, & Harb, 2005; Kwantes & Dickson, 2011). We argue that national cultural values will affect the likelihood that organizations will adopt diversity programs (Wood, 2003). According to value-belief theory (Hofstede, 1980; Triandis, 1994, 1995), prevailing societal values and beliefs affect the types of programs organizations within the society will adopt and see as legitimate. Thus, organizations operating in countries with national cultural values that are supportive of the values of diversity are more likely to adopt diversity programs than are organizations in nations with opposite values. Our focus on aspirational values as likely to affect the adoption of diversity programs rests on two findings from the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) project. First, within nations, aspirational values (‘should be’) often diverge from actual practices (‘as is’). Second, aspirational values are substantially more predictive of preferred leadership behaviors and characteristics than are actual practices (House et al., 2004). Given this linkage between aspirational values and leadership behaviors, it is likely that organizational leaders will support programs consistent with the aspirational values held by their society at large, especially if these programs enable their organizations to adapt to a changing environment and become more competitive and successful. Developing and implementing diversity programs is one way of addressing the changing demographics and meeting future challenges. In the following sections, we present our rationale for the effect of seven aspirational values on the adoption of diversity programs. Individualism/collectivism According to GLOBE (House et al., 2004), two interrelated dimensions (institutional and in-group) make up the construct of individualism/collectivism. Societies high in institutional collectivism encourage and reward collective action and distribution of resources. Societies high in individualism (i.e. low in institutional collectivism) emphasize individual uniqueness and rights, even at the expense of group loyalty. In-group collectivism is characterized by pride, loyalty and commitment to the organization or family. In contrast, individualism (i.e. low in-group collectivism) is characterized by an emphasis on the importance of personal needs and attitudes as determinants of social behavior. These distinctions suggest that organizations in collectivistic societies are more likely to emphasize group commonality, especially of the majority or dominant group or ethnicity, and de-emphasize the unique needs of individuals. In these societies, diversity programs focused on increasing the ratio of minority or nondominant groups is likely to be perceived as damaging to the commonality of the collective. On the other hand, because individualistic societies emphasize individual rights, and place less emphasis on 878 H. Peretz et al. distinctions between in-groups and out-groups, organizations in these societies are more likely to adopt diversity programs to help integrate diverse individuals into the workforce. Given the emphasis on equal rights, as well as on more rational, merit-based decisionmaking, individualistic societies are likely to view diversity programs as a means of promoting equal opportunity for those who are disadvantaged by being members of minorities or nondominant groups. Hypothesis 1: Organizations in societies low in institutional and in-group collectivism (i.e. high in individualism) will be more likely to adopt diversity programs than organizations in societies high in institutional and in-group collectivism. Power distance Power distance is the degree to which members of a collective expect power to be distributed equally (House et al., 2002, 2004). In high power distance societies, hierarchy is rigidly adhered to and privileges are distributed unequally. In such societies, higherlevel members are expected to preserve their relative advantage in status and power and maintain strong in-group relationships, thereby discouraging the inclusion of new and diverse groups. Consequently, organizations in such societies will typically be more concerned with maintaining the status quo by restricting the social mobility of groups traditionally lower in power and status. Diversity programs, which entail the increased inclusion of groups traditionally lower in power and status, wide sharing of information and the recognition of the legitimacy of groups that may be opposed to the status quo, are much more consistent with low power distance than high power distance societal values. In summary, diversity programs imply willingness on the part of those higher in power to include others or share power with them. Hypothesis 2: Organizations in societies low rather than high in power distance will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Uncertainty avoidance Uncertainty avoidance is defined as the extent to which a society, organization or group relies on social norms, rules and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events (House et al., 2002, 2004). Organizations embedded in high uncertainty-avoidance societies are more likely, relative to organizations embedded in low uncertainty-avoidance societies, to develop practices that avoid ambiguity, and are therefore less likely to adopt diversity programs. This is so for two reasons. First, societies high in uncertainty avoidance are resistant to change, and diversity programs imply a challenge to the status quo as well as the recognition of the legitimacy of alternative perspectives and values. Second, diversity programs raise the chances of conflict and unpredictable and negative social interactions among different groups, which can threaten the formal, and predictable patterns of interaction preferred in high uncertainty avoidance societies (Bassett-Jones, 2005; Chua, 2013). Hypothesis 3: Organizations in societies low rather than high in uncertainty avoidance will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Future orientation Future orientation is the degree to which organizations engage in future-oriented behaviors such as planning, investing in the future and delaying gratification (House et al., 2004). The International Journal of Human Resource Management 879 High future orientation entails investment and development by the organization to prepare the workforce to meet future organizational needs. Low future orientation, in contrast, is associated with the propensity to spend now rather than later, implying less willingness to invest for long-term prospects. Diversity programs, which tend to challenge the status quo and can create discomfort in the short run, go counter to the tendency of low futureoriented societies to prefer expediency in the near term and reject difficult programs that might improve long-term outcomes. Consequently, organizations embedded in futureoriented societies are more likely, relative to organizations embedded in present- or less future-oriented societies, to pursue workforce diversity to elicit a broader range of perspectives to facilitate organizational growth and development. Hypothesis 4: Organizations in societies high rather than low in future orientation will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Gender egalitarianism Gender egalitarianism refers to the degree to which societies or organizations minimize differences in gender roles. Gender egalitarianism includes acceptance of women in positions of authority, less occupational sex segregation and willingness to afford women greater decision-making in society. Societies low in gender egalitarianism are characterized by more rigid sex roles, higher occupational sex segregation and lower acceptance of women as decision-makers or authority figures (House et al., 2004). It follows that diversity programs, which typically aim to increase the voice, discretion and respect accorded women, are more consistent with high than low gender egalitarianism. By implication, societies that minimize gender role differences will also promote values that enhance acceptance of diversity in the workplace, resulting in the incorporation of different perspectives and insights positively related to organizational outcomes. Hypothesis 5: Organizations in societies high rather than low in gender egalitarianism will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Humane orientation Humane orientation refers to the extent to which individuals in societies or organizations encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring and kind to others. Societies high in humane orientation are likely to promote sensitivity to all forms of racial discrimination, whereas societies low in humane orientation place little emphasis on being sensitive to racial discrimination (House et al., 2004). Consequently, societies high in humane orientation will be more likely to promote acceptance and tolerance of people with diverse backgrounds, making the adoption of diversity programs more likely. Hypothesis 6: Organizations in societies high rather than low in humane orientation will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Performance orientation Performance orientation refers to the extent to which a community encourages and rewards innovation, high standards, excellence and performance improvement. Societies high in performance orientation value competitiveness are likely to emphasize training 880 H. Peretz et al. and development and view feedback as important for performance improvement. In contrast, societies low in performance orientation emphasize social relationships and harmony over performance improvement and tend to view performance feedback as overly judgmental. It is likely that societies high in performance orientation will be more accepting of programs that challenge the status quo, as well as programs that may increase competitiveness and effectiveness in the long run, even at the expense of short-term discomfort. In addition, leaders who are successful in high performance orientation societies tend to set ambitious goals, have high expectations and intellectually challenge their subordinates (House et al., 2004). It follows that diversity programs, which tend to challenge the status quo and increase the potential for discomfort in intergroup relations, are likely to be more accepted in societies high rather than low in performance orientation. Hypothesis 7: Organizations in societies high rather than low in performance orientation will be more likely to adopt diversity programs. Diversity programs and organizational outcomes: the moderating effect of national cultural practices The literature has shown mixed results on the effect of diversity on organizational outcomes (Cunningham & Sagas, 2004; Ely, 2004; Jackson & Joshi, 2011; McMahon, 2010). For example, some studies found that diverse groups outperformed homogeneous groups, while other studies failed to show this pattern (see, e.g. Baringa, 2007; BassettJones, 2005; Chua, 2013; Cox, Lobel, & McLeod, 1991; Ely, 2004; Homan, van Knippenberg, Van Kleef, & De Dreu, 2007; Mannix & Neale, 2005; O’Reilly, Caldwell, & Barnett, 1989; Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2010; Watson, Kumar, & Michaelsen, 1993). Two schools of thoughts have served as the basis for investigating the effects of diversity. The first is based on social identity and self-categorization (Tajfel, 1981; Turner, 1987), which posit that people have a need to maintain high self-esteem that, in part, is achieved by comparing the self to others. People who are similar to the self are considered in-group members while people who are different from the self are considered out-group members. By maximizing perceived group differences, people can strengthen their experience of in-group superiority, resulting in increased self-esteem. When diversity is high, this process will result in stronger in-group –out-group distinctions, leading to negative social processes that compromise group performance (Chua, 2013; Cunningham & Sagas, 2004; Ely, 2004; Stahl et al., 2010). The second approach argues, on the basis of information and decision-making theories, that diversity is likely to provide a broad range of skills, perspectives and insights, resulting in increased group creativity, problemsolving abilities and consequently performance outcomes (Cox, 1993; Cox & Blake, 1991; Ely 2004; Page, 2007; Thomas & Ely, 1996). The theoretical conflict and mixed findings suggest the potential role of moderators (Rousseau & Fried, 2001). One such moderator is cultural practices (‘as is’ practices), as distinguished from cultural values (aspirational values) in the GLOBE research program (House et al., 2004). Because aspirational values and cultural practices can diverge, programs adopted on the basis of an aspirational value will not necessarily elicit acceptance among employees or have the desired effects on behavior or other outcomes. In fact, cultural practices may constrain the effects of programs adopted on the basis of aspirational values. Examples of this constraining effect have been observed in the context of organizational diversity programs in the USA. Many firms express support for diversity in their mission statements, and have developed diversity initiatives involving hiring, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 881 promotion, career development, education and training, performance and accountability and work –life balance. However, the intended effects of such efforts (e.g. increased representation and advancement of women and minorities) are often limited by the prevailing skeptical attitudes and nonsupportive behaviors of employees and managers (Kossek & Lobel, 1996; Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak, 2000, 2005). Thus, the prevailing nonsupportive practices of many organizational members often constrain the potential of diversity programs, even when the aspirational values of top leaders support such programs. Moreover, given the prevalence of nonsupportive attitudes and behaviors, diversity programs may also elicit resistance and backlash (Thomas & Plaut, 2008). Consequently, we suggest that cultural practices will moderate the effects of organizational diversity programs on organizational outcomes. Hypotheses 1– 7 pertained to the main effects of aspirational values, stating in essence that certain national cultures (those characterized by high individualism, low power distance, low uncertainty avoidance, high future orientation, high gender egalitarianism, high humane orientation and high performance orientation) would be more likely to promote attention to diversity and support the adoption of diversity programs. However, national cultures having the same or a similar set of aspirational values may differ in their cultural practices, thereby moderating the effects of diversity programs on organizational outcomes (Kwantes & Dickson, 2011). In particular, societies with cultural practices opposite those listed above are expected to reduce acceptance of out-groups and diversity more generally, as such societies tend to be low in inclusion. Inclusion refers to the extent to which differences are respected and valued, and the participation and opportunities of diverse groups in the workplace are actively supported (Mor Barak, 2005; Roberson, 2006). Organizations may be high in diversity but low in inclusion (Mor Barak, 2005). Because programs aimed at increasing diversity generally are accompanied by organizational attempts to promote inclusion of out-groups, we suggest that such programs will produce tension in societies low in inclusion (i.e. those with values opposite those favoring diversity). Thus, we argue that if diversity programs are not congruent with the national cultural practices, employees’ satisfaction and commitment with their organization will be lower, and consequently they will tend to engage in withdrawal behaviors such as increased absenteeism and turnover (e.g. Arvey, McKay, Wilson, & Tonidandel, 2007; Hom & Kiniki, 2001; Mowday, Porter, & Steers, 1982). In summary, we expect that national cultural diversity practices will moderate the relationship between organizational diversity programs and the withdrawal behaviors of absenteeism and turnover. Of course, the withdrawal behaviors of absenteeism and turnover are potentially affected by a variety of additional work-related variables such as compensation, leadership and career opportunities (e.g. Hom & Griffeth, 1995; Johns, 2011). We therefore control for a number of these variables in order to more clearly reveal the effect of diversity programs on these withdrawal outcomes (see Method section). On the basis of this reasoning, we propose: Hypothesis 8a: Hypothesis 8b: The relationship between diversity programs and absenteeism will be moderated by national cultural practices, such that when these are supportive of diversity, the relationship between diversity programs and absenteeism will be stronger than when cultural practices are not supportive of diversity. The relationship between diversity programs and turnover will be moderated by national cultural practices, such that when these are supportive of diversity, the relationship between diversity programs 882 H. Peretz et al. and turnover will be stronger than when cultural practices are not supportive of diversity. Furthermore, absenteeism and turnover are expected to adversely affect the workforce’s effectiveness, resulting in reduced organizational performance and innovation (cf. Biron & De Reuver, 2013; Bycio, 1992; Glebbeek & Bax, 2004; Ostergaard, Timmermans, & Kristinsson, 2011; Roth, Huffcutt, & Bobko, 2003; Westwood & Low, 2003). Thus, we propose that absenteeism and turnover will mediate the relationship of diversity programs with performance and innovation. We consider absenteeism and turnover as mediators to performance and innovation because these withdrawal indicators have been long used as indicators of employee morale, satisfaction and commitment (Hom & Griffeth, 1995; Mowday et al., 1982; Navrbjerg & Minbaeva, 2009; Somers, 1995; Ybema, Smulders, & Bongers, 2010). These psychological experiences, in turn, affect behavioral outcomes such as work performance and innovation (Bukchin & Cohen, 2013; Hom & Griffeth, 1995). Thus, we propose: Hypothesis 9a: Hypothesis 9b: The relationship between diversity programs and performance and innovation will be mediated by employee absenteeism, such that stronger diversity programs will be related to lower employee absenteeism, which in turn will be related to higher organizational performance and innovation. The relationship between diversity programs and performance and innovation will be mediated by employee turnover, such that stronger diversity programs will be related to lower employee turnover, which in turn will be related to higher organizational performance and innovation. The conceptual model guiding our study is presented in Figure 1. Method Sample The study was conducted using a sample drawn from the 2009–2010 Cranfield Network on Comparative Human Resource Management (Cranet) project data-set. The Cranet project was established in 1989 by a network of universities and business schools in five European countries, with the purpose of promoting international comparative research on HRM. Currently, universities from 39 countries around the world participate in the project, with each country represented by one university. National Cranet representatives collect data in their respective countries using a standardized questionnaire. The data are then pooled into a single database. Each country questionnaire is back-translated (Brislin, 1970) and its contents are carefully reviewed by local HR experts to ensure equivalency of terms. Questionnaires are addressed to the most senior HR/personnel specialist in each organization. Cranet partners are required to send the questionnaire to a representative sample of organizations with over 100 employees. Questions cover major areas of HRM policies and practices at the organizational level. Rather than tapping personal opinions, questions are designed to seek factual answers (numbers or percentages) or a yes/no response to factual questions (e.g. do you use panel interviews for selection of managers?). (For more on the Cranet project, see Brewster, Mayrhofer, & Morley, 2004.) The criterion for selecting organizations for the present study was the availability of data on cultural values and practices (see below). Our overall sample consisted of 5000 organizations from 22 countries: Australia (110), Austria (203), Denmark (362), Finland The International Journal of Human Resource Management National Level Organizational Level National Cultural Values: Institutional collectivism, In-group collectivism, Power distance, Uncertainty avoidance, Future orientation, Gender egalitarianism, Humane orientation, Performance orientation Diversity Programs Cultural Practices: Institutional collectivism, In-group collectivism, Power distance, Uncertainty avoidance, Future orientation, Gender egalitarianism, Humane orientation, Performance orientation Withdrawal Behavior: Absenteeism and Turnover 883 Covariates: Unemployment rate Labor force participation rate Innovation Performance Covariates: Size Industry Sector Male/female proportion Union density Training Benefits Career development Compensation Figure 1. Conceptual model. (136), France (157), Germany (420), Greece (214), Hungary (139), Ireland (103), Israel (114), Italy (157), Japan (389), the Netherlands (116), Philippines (33), Russia (56), Slovenia (219), South Africa (192), Sweden (282), Switzerland (99), Taiwan (229), the USA (1052) and the UK (218). We present more information about the sample’s organizational background in our description of the control variables (see below). Variable measurement Absenteeism was captured by a single item asking about the average annual absenteeism, measured as annual number of days absent per employee (mean ¼ 7.91; SD ¼ 6.51). 884 H. Peretz et al. Turnover was captured by a single item asking about average yearly turnover percentage in the organization (mean ¼ 11.52; SD ¼ 12.14). Because of the non-normal distribution of the absenteeism and turnover variables, we applied a square root transformation to them before the analysis. Organizational outcomes: respondents were asked to compare their organization to other organizations in the same sector with regard to its (1) innovation level, (2) service quality level, (3) productivity level, (4) profitability level and (5) innovation level, and to rate them on a five-point scale with labels 1 ¼ poor or at the low end of the industry, 2 ¼ below average, 3 ¼ average or equal to the competition, 4 ¼ better than average and 5 ¼ superior. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) indicated that the two-factor model, in which service quality, productivity and profitability loaded on one factor, and innovation loaded on a second factor, fit the data well (x 2 ¼ 43.5, NFI ¼ 0.97, RMSEA ¼ 0.04, SRMR ¼ 0.03, GFI ¼ 0.98) and significantly better than an alternative model in which all four items loaded on a single factor (x 2 ¼ 78.7 p , 0.01, NFI ¼ 0.91, RMSEA ¼ 0.08, SRMR ¼ 0.06, GFI ¼ 0.92). Consequently, innovation was captured using an assessment of innovation rate (mean ¼ 3.41; SD ¼ 0.98). To capture organizational performance, we created a performance index, which was a composite index based on the mean of three separate performance outcomes variables. The index included assessments of (1) level of service quality (mean ¼ 3.86; SD ¼ 0.78), (2) level of productivity (mean ¼ 3.55; SD ¼ 0.86) and (3) level of profitability (mean ¼ 3.37; SD ¼ 0.97). Each item (innovation, service quality, productivity and profitability) was rated on a scale from 1 to 5. The reliability of the performance index was a ¼ 0.74 (mean ¼ 3.62; SD ¼ 0.71). Table 1 presents reliabilities, means and SD of this index by country. Table 1. country. Reliabilities, means and SDs of performance index and diversity programs index by Performance index Country Australia Austria Denmark Finland France Germany Greece Hungary Ireland Israel Italy Japan The Netherlands Philippines Russia Slovenia South Africa Sweden Switzerland Taiwan UK USA Total/overall Diversity programs index N Cronbach’s a Mean (SD) Cronbach’s a Mean (SD) 110 203 362 136 157 420 214 139 103 114 157 389 116 33 56 219 192 282 99 229 218 1052 5000 0.63 0.69 0.67 0.63 0.68 0.64 0.70 0.71 0.64 0.61 0.66 0.77 0.60 0.75 0.83 0.69 0.77 0.54 0.65 0.87 0.71 0.74 0.77 3.75 (0.59) 3.78 (0.63) 3.58 (0.66) 3.56 (0.64) 3.54 (0.66) 3.67 (0.59) 3.96 (0.68) 3.55 (0.71) 3.77 (0.65) 3.65 (0.59) 2.61 (0.55) 3.29 (0.73) 3.55 (0.48) 3.63 (0.72) 3.60 (0.94) 3.67 (0.61) 3.65 (0.75) 3.48 (0.52) 3.75 (0.58) 3.72 (0.79) 3.27 (1.12) 3.90 (0.72) 3.62 (0.71) 0.94 0.90 0.86 0.86 0.83 0.83 0.94 0.89 0.95 0.94 0.86 0.91 0.87 0.97 0.92 0.92 0.94 0.83 0.87 0.92 0.95 0.94 0.91 3.07 (4.85) 3.89 (5.05) 4.41 (3.38) 3.26 (3.26) 2.30 (3.00) 2.67 (2.89) 2.46 (4.58) 2.39 (4.92) 2.28 (4.92) 5.20 (6.08) 3.75 (3.83) 2.14 (5.62) 2.59 (3.50) 3.00 (7.05) 2.92 (4.37) 2.70 (4.36) 3.31 (7.10) 2.90 (2.44) 4.27 (4.35) 3.40 (5.03) 2.10 (4.41) 4.91 (5.85) 3.62 (4.86) The International Journal of Human Resource Management 885 Our independent variable, diversity programs, was measured by an index consisting of three items asking whether the organization had programs regarding (1) recruitment, (2) training and (3) career progression. Each of these items contained sub-items asking whether the program entailed special efforts in employment for the following groups (yes or no): (1) ethnic minorities, (2) older workers (aged 50 plus), (3) people with disabilities, (4) women, (5) mothers returning to work, (6) low-skilled labor and (7) younger workers (under 25 years old). CFAs indicated that a one-factor model (a single index consisting of the three diversity dimensions) fit the data well (x 2 ¼ 48.3, NFI ¼ 0.96, RMSEA ¼ 0.04, SRMR ¼ 0.04, GFI ¼ 0.97) and significantly better than alternative models (e.g. x 2 ¼ 88.6. p , 0.01, NFI ¼ 0.88, RMSEA ¼ 0.07, SRMR ¼ 0.08, GFI ¼ 0.89 for the model in which each dimension loaded on a separate factor). In addition, the consistent correlation between the different diversity dimensions also justified their incorporation into one scale, as measured by the diversity programs index. The reliability of this index was a ¼ 0.91 (mean ¼ 3.62; SD ¼ 4.86, range 0– 21). Table 1 presents reliabilities, means and SDs of this index by country. Because of the non-normal distribution of the diversity programs index, we applied a square root transformation to it before the analysis (mean ¼ 1.36, SD ¼ 0.54). Using the Shapiro – Wilk test, we confirmed that the distribution was normal after the transformation. In addition, for both performance index and diversity programs index variables, we assessed measurement invariance (MI) by goodness of fit index (GFI) using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results for the performance index were NFI ¼ 0.995, IFI ¼ 0.902 and CFI ¼ 0.895. The results for the diversity programs index were NFI ¼ 0.897, IFI ¼ 0.901 and CFI ¼ 0.892, indicating there were no MI issues. Cultural values and cultural practices were obtained from the GLOBE database (House et al., 2004). GLOBE is a multi-phase, multi-method project, in which investigators spanning the world examine interrelationships between societal culture, organizational culture and organizational leadership. The GLOBE project was founded in 1993; today, scholars from 61 countries, representing all major regions of the world, are engaged in this long-term programmatic series of cross-cultural leadership studies (House et al., 2004). The GLOBE culture-level data were collected using surveys from middle managers (an average of 251 per country). Individual respondents were aggregated to the country level. All respondents indicated that they had an average full-time work experience of 19.2 years, of which an average of 10.5 years were spent as managers. The GLOBE data-set limits its sampling to three industries (food processing, financial services and telecommunications services) because these industries were present in all countries of the world. Multinational corporations were excluded because their members would be from multiple cultures. A total of 62 countries were included in the GLOBE sample, with a total of 17,730 individuals from 951 organizations. (For more information about the GLOBE sample, please see House et al., 2004, Chapter 6, Research Design.) Survey items measured seven national cultural values and seven national cultural practices: collectivism (both institutional and in-group), power distance, uncertainty avoidance, future orientation, gender egalitarianism, humane orientation and performance orientation, on a 1 (low) to 7 (high) scale. National cultural values refer to the society’s ideal (aspirational) values, while national cultural practices indicate current perceptions of practices within the society. An example of a collectivism cultural value was ‘I believe that the economic system in this society should be designed to maximize . . . ’ The corresponding cultural practice item was ‘The economic system in this society is designed to maximize . . . ’. 886 H. Peretz et al. Controls: We included several control measures to remove the influences of other variables related to the outcomes in our model. First, we controlled for five organizational background variables, taken from the Cranet data: (1) organizational size (the total number of employees in the organization). Because of the non-normal distribution of this variable, we divided the distribution into three categories based on percentage: small (scored 1, 33.4%), medium (scored 2, 33.2%) and large (scored 3, 33.4%); (2) industry (whether the organization provided services (health, education, research, finance, transportation, political, entertainment and communication, totaling 69.4%) or products (food, chemical products, textile, machinery, knowledge-based products, totaling 30.6%); (3) sector (public and private, 20% and 80%, respectively); (4) male/female proportion (the percentage of male employees in a given organization divided by the percentage of female employees; mean ¼ 2.99; SD ¼ 4.66); and (5) union density (extent to which trade unions influence the organization; mean ¼ 1.29; SD ¼ 1.18). In addition, we controlled for four more HR practice that can potentially affect withdrawal behavior: (1) training (annual spending on training, mean ¼ 15.23; SD ¼ 14.83); (2) benefits in excess of statutory requirements (index based on the sum of workplace childcare, childcare allowance, career break schemes, maternity leave, paternity leave, pension schemes, education/training break and private health care schemes, mean ¼ 3.15; SD ¼ 1.19); (3) career development (index based on the sum of participation in project team work, networking, formal career plans, development centers, planned job rotation, leadership development programs, expatriate assignments, coaching, mentoring, e-learning, mean ¼ 3.02; SD ¼ 1.15); and (4) compensation (index based on the sum of bonus based on individual performance, bonus based on team performance, flexible benefits, mean ¼ 1.22; SD ¼ 1.04). Benefits, opportunities for career development and compensation are important contextual variables that have been shown to influence absenteeism and turnover (e.g. Hom & Griffeth, 1995). Training also was found to affect absenteeism and turnover (Sieben, 2007) because it contributes to career development (e.g. Whitely & Coestier, 1993). Organizational size may also be related to diversity, such that large organizations may have more opportunities and resources to invest in diversity programs. Similarly, high representation of unions (union density) may be related to stronger diversity programs. Finally, because labor market conditions can have a major influence, data on two national-level background variables were taken from each country’s official bureau of statistics database: unemployment rate (mean ¼ 8.93; SD ¼ 6.22) and labor force participation rate (ratio between the labor force and the overall size of the same age range, mean ¼ 66.19; SD ¼ 8.13). The literature demonstrates strong support for the relationship between those two variables and diversity (e.g. Izraeli & Murphy, 2003; Simon & Nardinelli, 1992). Analytic procedure The present data contained a hierarchical structure in which organizational-level variables were nested within countries. In addition, we have multilevel mediation and moderation hypotheses (i.e. Hypotheses 8a, 8b, 9a and 9b). The covariance among the Level 1 (i.e. the organizational-level) random effects had to be estimated in order to estimate random indirect effects and corresponding standard errors (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006). Therefore, we used multilevel modeling to estimate the hypothesized multilevel relationships using Mplus 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 2007). We used the Monte Carlo method recommended by Preacher, Zyphur and Zhang (2010) to estimate confidence intervals for the hypothesized multilevel mediated relationships to determine their significance. To avoid giving The International Journal of Human Resource Management 887 disproportionate weight to countries with larger sample sizes, we counterweighted the indicators by sample size (see Cullen, Parboteeah, & Hoge, 2004). Results Means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables are presented in Table 2. Model estimation To estimate the hypothesized model (see Figure 1), we specified the Level 1 (i.e. organizational level) diversity, absenteeism, turnover, performance, innovation and organizational level controls slopes to be random. At Level 2 (i.e. country level), we specified cultural values, cultural practices and country level controls. To facilitate the interpretation of the findings, Level 2 variables were all grand-mean centered. Level 1 variables were group-mean centered to obtain an unbiased estimate of the cross-level interactions (Enders & Tofighi, 2007; Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). Finally, although it is difficult to estimate precise effect sizes in cross-level models, we report Snijders and Bosker’s (1999) overall pseudo R 2 (, R 2) and incremental pseudo R 2 (D , R 2) for the models; these estimates are based on proportional reduction of Level 1 and Level 2 errors owing to predictors in the model (Recchia, 2010). Tests of hypotheses Hypotheses 1 –7 Hypotheses 1–7 predicted that national cultural values would be associated with the diversity index. The results (see Table 3) indicated that institutional collectivism and in-group collectivism were negatively related to the diversity programs index (20.28** and 20.23**, respectively), confirming Hypothesis 1. Power distance was negatively related to the diversity programs index (20.17**), confirming Hypothesis 2, and uncertainty avoidance was also negatively related to the diversity programs index (20.21**), confirming Hypothesis 3. In addition, the future orientation, gender egalitarianism and performance orientation values were positively related to the diversity programs index (0.18**, 0.19**, 0.21**), confirming Hypotheses 4, 5 and 7, respectively. In contrast, Hypothesis 6, which predicted that humane orientation would be positively related to the diversity programs index, was not confirmed (0.07, ns). In addition, the covariates of organizational size, career development (at the organizational level) and labor force participation rate (at the country level) were also associated with the diversity programs index (see Table 3). Hypotheses 8a and 8b Hypothesis 8a predicted that cultural practices would moderate the relationship between the diversity programs index and absenteeism, and Hypothesis 8b predicted that cultural practices would moderate the relationship between the diversity programs index and turnover. The multilevel modeling results related to Hypothesis 8a found positive effects of future orientation and performance orientation practices on the random slope between diversity programs index and absenteeism (0.26**, 0.11*), and negative effects of power distance and uncertainty avoidance practices on the random slope between the diversity programs index and absenteeism (2 0.24**, 2 0.21**). Other practices (institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, future orientation and gender egalitarianism) did not 1 Diversity (transformed)a 2 Absenteeism 3 Turnover 4 Innovation 5 Performance 6 Institutional collectivism value 7 In-group collectivism value 8 Power distance value 9 Uncertainty avoidance value 10 Future orientation value 11 Gender egalitarianism value 12 Humane orientation value 13 Performance orientation value 14 Institutional collectivism practice 15 In-group collectivism practice 16 Power distance practice 17 Uncertainty avoidance practice 18 Future orientation practice Variable 2 3 4 6.51 20.15** 12.19 20.31** 0.05 0.98 0.19** 20.18** 20.11** 0.71 0.17** 20.23** 20.20** 0.55** 0.41 20.31** 20.38** 20.19** 20.03 1 20.04 0.02 5 0.37** 6 7 20.09* 20.02 0.26** 20.34** 20.31** 0.10* 20.12** 20.16** 20.06 20.07 20.07 0.12** 20.06 5.37 0.26 4.46 0.71 4.48 0.63 5.01 0.40 20.18** 20.05 0.14** 0.23** 20.38** 0.09* 0.04 20.01 4.70 0.56 20.16** 20.22** 20.40** 20.08 4.21 0.41 0.04 0.05 0.32** 9 20.18** 0.14** 0.17** 0.39** 11 0.21** 0.05 20.29** 20.49** 20.12** 20.18** 20.26** 20.39** 13 20.21** 20.18** 20.42** 14 0.19** 15 16 0.03 20.05 20.07 20.58** 20.63** 17 0.17** 0.45** 0.21** 20.63** 20.40** 20.63** 20.17** 20.18** 0.04 0.07 0.31** 20.47** 0.21** 12 0.25** 20.44** 20.64** 20.49** 0.13** 20.44** 20.42** 20.03 20.05 20.61** 20.11* 0.04 10 0.26** 20.12** 20.15** 20.25** 20.31** 0.26** 0.15** 20.33** 20.18** 20.04 0.23** 0.39** 0.47** 20.06 20.01 20.16** 20.25** 20.31** 20.62** 0.10** 0.09* 20.07 20.08* 8 0.34** 20.24** 20.06 0.09* 20.17** 20.05 20.05 20.03 0.11** 0.03 0.11** 20.03 5.52 0.17 20.02 0.04 0.22** 20.39** 20.18** 4.84 0.33 0.02 0.13** 20.14** 20.03 0.21** 20.20** 20.09* 20.05 5.25 0.30 4.28 0.48 20.25** 20.08* 20.03 3.07 0.76 20.21** 20.25** 20.23** 20.09* 20.13** 20.35** 20.25** 5.66 0.23 20.25** 20.27** 20.13** 20.04 7.91 11.52 3.41 3.62 4.48 1.36 0.54 Mean SD Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations. 18 20 (Continued) 19 888 H. Peretz et al. 3 0.25** 20.16** 20.08 0.08 3.34 0.43 0.07 0.31** 3.98 0.45 0.20** 20.08 2 0.23** 1 3.50 0.37 Mean SD 0.13** 0.04 0.03 4 8 9 10 0.26** 20.40** 0.21** 0.17** 20.17** 20.12** 20.26** 20.27** 7 20.53** 20.28** 20.31** 20.43** 20.05 6 0.09* 20.10** 20.15** 0.03 0.02 5 Note: N ¼ 5000. Country-level means assigned down to organizational level. *p , 0.05; **p , 0.01. Two-tailed test. a Square root transform. 19 Gender egalitarianism practice 20 Humane orientation practice 21 Performance orientation practice Variable Table 2 – continued 0.17** 0.16** 0.44** 11 0.14** 14 0.04 0.03 0.04 15 18 0.21** 0.22** 17 19 0.48** 0.42** 0.41** 0.42** 0.04 16 20 0.17** 20.15** 20.63** 0.26** 0.69** 0.15** 0.23** 0.08 0.10* 20.51** 13 0.52** 20.16* 0.21* 12 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 889 890 H. Peretz et al. Table 3. Analysis of the relationship between cultural values and diversity programs. Diversity programs Variables Level 1 main effects Size Industry Sector Male/female proportion Union density Training Benefits Career development Compensation Level 2 main effects: Unemployment rate Labor force participation rate Institutional collectivism value In-group collectivism value Power distance value Uncertainty avoidance value Future orientation value Gender egalitarianism value Humane orientation value Performance orientation value ,R 2 D , R2 Model 1a Model 2b 0.13** (0.07) 2 0.02 (0.06) 0.05 (0.10) 0.04 (0.02) 2 0.07 (0.04) 0.04 (0.03) 0.06 (0.05) 0.17** (0.08) 0.06 (0.06) 0.12** (0.06) 2 0.02 (0.06) 0.02 (0.04) 0.01 (0.03) 2 0.06 (0.04) 0.03 (0.02) 0.06 (0.05) 0.16** (0.07) 0.05 (0.06) 2 0.07 (0.03) 0.24** (0.08) 2 0.06 (0.02) 0.22** (0.07) 2 0.28** (0.06) 2 0.23** (0.04) 2 0.17** (0.04) 2 0.21** (0.03) 0.18** (0.05) 0.19** (0.08) 0.07 (0.08) 0.21** (0.06) 0.23 0.11 0.12 Note: N ¼ 5000 organization (Level 1) in 22 countries (Level 2). Unstandardized estimates (are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Pseudo R 2 values (,R 2) estimate the amount of total variance (both Level 1 and Level 2) in the dependent variable captured by predictors in the model. *p , 0.05; **p , 0.01. a Model includes controls only. b model includes controls and predictors. have moderating effects on the relationship between the diversity programs index and turnover. Thus, Hypothesis 8a was partially supported. Regarding Hypothesis 8b, the results demonstrated a positive effect of future orientation and humane orientation practices on the random slope between the diversity programs index and turnover (0.18**, 0.28**), and negative effects of institutional collectivism, power distance and uncertainty avoidance practices on the random slope between the diversity programs index and turnover (2 0.19**, 2 0.29**, 2 0.22**). Other cultural practices (in-group collectivism, gender egalitarianism and performance orientation) did not have moderating effects on the relationship between the diversity programs index and turnover. Thus, Hypothesis 8b was partially supported (see Table 4). Following Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken’s (2003) recommendations (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006), we plotted this interaction at conditional values of the cultural practices (1 SD above and below the means) (see Figures 2 and 3) When future orientation, humane orientation and performance orientation were higher, and institutional collectivism, power distance and uncertainty avoidance practices were lower, the relationship between the diversity program index and turnover and absenteeism was stronger. For example, the diversity program index was more strongly and more negatively related to turnover and absenteeism when power distance Level 1 main effects Size Industry Sector Male/female proportion Union density Training Benefits Career development Compensation Diversity programs Level 2 main effects Unemployment rate Labor force participation rate Institutional collectivism practice In-group collectivism practice Power distance practice Uncertainty avoidance practice Future orientation practice Gender egalitarianism practice Humane orientation practice Performance orientation practice Cross-level interactions Diversity £ institutional collectivism practice Diversity £ in-group collectivism practice Diversity £ power distance practice Diversity £ uncertainty avoidance practice Diversity £ future orientation practice Diversity £ gender egalitarianism practice Variables 0.11* (0.03) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.04 (0.02) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.10** (0.04) 2 0.12** (0.05) 2 0.12** (0.06) 2 0.09* (0.05) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.34** (0.13) 2 0.05 (0.04) 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.15** (0.09) 2 0.05 (0.03) 2 0.07 (0.05) 2 0.38** (0.07) 2 0.36** (0.08) 2 0.06 (0.04) 0.08 (0.06) 2 0.06 (0.04) 20.06 (0.04) 0.02 (0.01) Model 2b 0.13** (0.05) 20.02 (0.01) 20.04 (0.02) 20.02 (0.01) 20.12** (0.04) 20.14** (0.06) 20.13** (0.06) 20.10* (0.07) 20.01 (0.00) Model 1a Turnover 2 0.19** (0.08) 2 0.07 (0.09) 2 0.29** (0.14) 2 0.22** (0.07) 0.18** (0.09) 0.06 (0.08) 2 0.05 (0.04) 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.14** (0.08) 2 0.03 (0.02) 2 0.06 (0.03) 2 0.36** (0.05) 2 0.34** (0.08) 2 0.06 (0.04) 0.08 (0.06) 2 0.06 (0.04) 0.11* (0.03) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.04 (0.02) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.09* (0.04) 2 0.12** (0.05) 2 0.12** (0.06) 2 0.09* (0.05) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.31** (0.11) Model 3c 20.05 (0.03) 0.10* (0.06) 0.18**(0.04) 0.01 (0.00) 20.12* (0.06) 20.02 (0.01) 20.01 (0.00) 20.14** (0.06) 20.11* (0.03) 20.12** (0.04) 20.01 (0.03) Model 1a 2 0.05 (0.03) 0.10* (0.06) 2 0.12** (0.04) 2 0.06 (0.05) 2 0.05 (0.05) 2 0.29** (0.07) 2 0.33** (0.06) 2 0.19** (0.05) 0.07 (0.06) 2 0.16** (0.05) 0.17**(0.04) 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.10* (0.05) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.13** (0.06) 2 0.10* (0.03) 2 0.11** (0.04) 2 0.01 (0.03) 2 0.13** (0.05) Model 2b Absenteeism Table 4. Analysis of the moderator effects of cultural practices on the relationship between diversity programs and turnover and absenteeism. (Continued) 2 0.08 (0.06) 2 0.06 (0.07) 2 0.24** (0.13) 2 0.21** (0.11) 0.26** (0.14) 0.07 (0.09) 2 0.04 (0.03) 0.09* (0.04) 2 0.12** (0.04) 2 0.05 (0.04) 2 0.04 (0.05) 2 0.21** (0.05) 2 0.22** (0.08) 2 0.18** (0.05) 0.06 (0.04) 2 0.15** (0.04) 0.17**(0.04) 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.10* (0.05) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.13** (0.06) 2 0.10* (0.03) 2 0.11** (0.04) 2 0.01 (0.03) 2 0.12**(0.06) Model 3c The International Journal of Human Resource Management 891 0.08 Model 1 a 0.21 0.13 Model 2 b Turnover 0.28** (0.12) 2 0.03 (0.04) 0.32 0.11 Model 3 c .12 Model 1 a Note: N ¼ 5000 organization (Level 1) in 22 countries (Level 2). Unstandardized estimates are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. *p , 0.05; **p , 0.01. a Model includes controls only. b Model includes controls and main effects. c Model includes controls, main effects and cross-level interactions. Diversity £ humane orientation practice Diversity £ performance orientation practice ,R 2 D , R2 Variables Table 4 – continued .23 0.11 Model 2b Absenteeism 0.06 (0.07) 0.11* (0.05) .30 0.07 Model 3c 892 H. Peretz et al. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 893 Figure 2. Interaction effect of future orientation practice and diversity program on turnover (average yearly turnover percentage). was low rather than high. More specifically, as shown in Figure 3, in high power distance societies (mean þ 1 SD ¼ 5.41), adoption of diversity programs (mean þ 1 SD ¼ 1.90) led to 7.8 annual absent days per employee and low adoption of diversity programs (mean þ 1 SD ¼ 0.82) led to 8.4 annual absent days per employee (0.6 days difference). However, in low power distance societies (mean 2 1 SD ¼ 4.61), high adoption of diversity programs led to 6.6 annual absent days per employee and low adoption of diversity programs led to 8.5 annual absent days per employee (1.9 days difference). These results support Hypothesis 8b. In addition to the moderator effects, we found negative main effects of the diversity programs index on absenteeism (20.12**) and turnover (20.31**), such that the higher the diversity programs index, the lower the absenteeism and turnover. We also found main effects of the cultural practices of institutional collectivism, uncertainty avoidance and future orientation on turnover (20.14**, 20.34**, 20.36**), and institutional collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, future orientation, gender egalitarianism and performance orientation practices on absenteeism (20.12**, 20.21**, 20.22**, 20.18**, 20.14*), such that the higher those cultural practices, the lower the absenteeism and turnover rate (see Table 4). Hypotheses 9a and 9b Hypotheses 9a and 9b predicted, respectively, that turnover and absenteeism would mediate the relationship between the diversity program index and between innovation and 894 H. Peretz et al. Figure 3. Interaction effect of power distance practice and diversity program on absenteeism (average annual days per employee). organizational performance. In order to examine the hypotheses we utilized parametric bootstrapping using the Monte Carlo method, which is appropriate in a multilevel modeling context (see Preacher & James, 2012). As shown in Table 5, the diversity program index was negatively related to turnover and absenteeism (2 0.36**, 2 0.10*), and turnover and absenteeism were negatively related to innovation (2 0.09**, 2 0.17**) and performance (2 0.15**, 2 0.19**). Regarding Hypothesis 9a (indirect effects via absenteeism), with 20,000 Monte Carlo replications, results showed that there was a positive indirect relationship between the diversity programs index and innovation via absenteeism (indirect effect 0.09*, 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI [0.06, 0.11]) and between the diversity programs index and performance via absenteeism (indirect effect 0.11*, 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI [0.06, 0.13]), supporting Hypothesis 9a. Concerning Hypothesis 9b (indirect effects via turnover), the results showed a positive indirect relationship between the diversity programs index and innovation via turnover (indirect effect 0.18**, 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI [0.13, 0.21]), and between the diversity programs index and performance via turnover (indirect effect 0.13**, 95% biascorrected bootstrap CI [0.07, 0.14]). Therefore, Hypothesis 9b was supported. We should note that after adding the indirect effects to the model, the coefficients of most of the direct effects (turnover to performance and absenteeism to innovation and performance) were reduced (2 0.07*, 2 0.10**, 2 0.09, respectively), suggesting partial mediation, and only Model 1 Model 1 a b Model 2 Absenteeism 0.10* (0.06) 0.12 0.02 (0.01) 0.17 0.09 0.18 0.06 0.10* (0.06) 2 0.05 (0.03) 2 0.05 (0.03) 2 0.05 (0.04) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.13** (0.06) 2 0.10* (0.06) 2 0.11** (0.07) 2 0.01 (0.03) 2 0.13** (0.06) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.14** (0.06) 2 0.11* (0.03) 2 0.12** (0.04) 2 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.01 (0.03) 2 0.34** (0.13) 2 0.10** (0.07) 2 0.12** (0.05) 2 0.12** (0.06) 2 0.09* (0.05) 0.11* (0.03) 0.18**(0.04) 0.17**(0.04) 2 0.02 (0.01) 0.01 (0.00) 0.01 (0.00) 2 0.04 (0.02) 2 0.12* (0.06) 2 0.10* (0.05) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.02 (0.01) 2 0.02 (0.01) Model 2 b Model 2 b Innovation Model 3 c Model 1 a 0.07 0.09* (0.06) 0.04 (0.03) 0.02 (0.01) 0.03 (0.02) 0.08* (0.05) 0.04 (0.03) 0.21** (0.12) 0.02 (0.01) 0.03 (0.02) 0.08* (0.05) 0.03 (0.03) 0.20** (0.11) 0.17 0.10 0.09* (0.06) 0.04 (0.03) 0.03 (0.02) 0.07 (0.04) 0.08* (0.03) 0.07 (0.04) 0.11* (0.05) 0.12** (0.05) 0.21 0.04 0.18 0.11 0.23 0.05 0.11* (0.06) 0.05 (0.04) 0.03 (0.02) 0.18** (0.09) 0.06 (0.04) 0.03 (0.02) 0.13** (0.06) 0.07 0.07 (0.04) 0.08* (0.03) 0.07 (0.04) 0.11* (0.05) 0.12** (0.05) 0.01 (0.01) 0.03 (0.02) 0.09* (0.06) 0.04 (0.03) ‘Model 3c 2 0.19** (0.08) 2 0.09 (0.04) 2 0.15** (0.06) 2 0.07* (0.03) 0.07 (0.04) 0.08* (0.03) 0.07 (0.04) 0.11* (0.05) 0.12** (0.05) 0.01 (0.01) 0.03 (0.02) 0.09* (0.06) 0.04 (0.03) Model 2b Performance 0.09* (0.04) 0.08* (0.05) 0.06 (0.04) 0.03 (0.03) 2 0.17** (0.06) 2 0.10** (0.03) 2 0.09* (0.04) 2 0.04 (0.05) 0.02 (0.01) 0.03 (0.02) 0.08* (0.05) 0.03 (0.03) 0.20** (0.12) 2 0.11* (0.05) 2 0.11* (0.05) 2 0.10* (0.03) 0.01 (0.01) 2 0.09* (0.03) 2 0.08* (0.03) 2 0.08* (0.03) 0.03 (0.02) 0.10* (0.07) 0.10* (0.07) 0.09* (0.05) 0.09* (0.06) 0.04 (0.04) 0.04 (0.04) 0.04 (0.04) 0.04 (0.03) Model 1 a Note: N ¼ 5000 organizations (Level 1) in 22 countries (Level 2). Unstandardized estimates are reported with standard errors in parentheses. *p , 0.05; **p , 0.01. a Model includes controls only. b Model includes controls and direct effects. Level 1 main effects Size 0.13** (0.05) Industry 2 0.02 (0.01) Sector 2 0.04 (0.02) Male/female 2 0.02 (0.01) proportion Union density 2 0.12** (0.04) Training 2 0.14** (0.06) Benefits 2 0.13** (0.06) Career 2 0.10* (0.07) development Compensation 2 0.01 (0.00) Diversity programs Absenteeism Turnover Level 2 main effects Unemployment 2 0.06 (0.04) rate Labor force 0.02 (0.01) participation rate Indirect effects Diversity programs via absenteeism Diversity programs via turnover ,R 2 0.08 D , R2 Variables a Turnover Table 5. Analysis of the mediation effects of turnover and absenteeism on the relationship between diversity programs and innovation and performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 895 896 H. Peretz et al. the direct effect of turnover on innovation become nonsignificant (2 0.04, ns), suggesting full mediation (see Table 5, Model 3). Integrative model In summary, we found that (1) national cultural values (collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, future orientation, gender egalitarianism and performance orientation) were associated with the diversity programs index; (2) the diversity programs index was more strongly related to turnover in societies characterized by lower levels of the cultural practices of power distance, collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, and higher levels of performance orientation and humane orientation; (3) the diversity programs index was more strongly related to absenteeism in societies characterized by lower levels of the cultural practices of power distance and uncertainty avoidance, and higher levels of performance orientation; and (4) the diversity programs index was related to outcomes (both innovation and performance) via the indirect effects of turnover and absenteeism. Taken together, these findings suggest that the indirect (i.e. mediated) effect of the diversity programs index on innovation and performance varies as a function of the moderators. Specifically, cultural practices, owing to their moderating influence on the relationship between the diversity programs index and between turnover and absenteeism, hold the potential to enhance or diminish the indirect effect of the diversity programs index on innovation and performance. Thus, to more fully evaluate the results, we also examined a moderation-mediation model, an integrative approach in which mediated and moderated relationships are examined simultaneously (see Bauer et al., 2006). This integrative approach allowed us to accurately estimate how the relative sizes of the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable via the mediators varied under differing levels of the moderators. To account for the large number of variables in our study (total of 31), and to simplify the complex integrated model, for each set of national-level measures (cultural values and cultural practices) we created an index, using the average score, after reverse-scoring items for consistency with items worded in standard fashion. The model fit indexes indicates high fit (RMSEA ¼ 0.03, NFI ¼ 0.96) of the integrated model. Specifically, addition of the moderator (i.e. cultural practices index) indicated that the indirect effect of the diversity programs index on innovation and performance through turnover and absenteeism differed as a function of this moderator. That is, the indirect effect of the diversity programs index on innovation and organizational performance via turnover was stronger at high (þ1 SD) cultural practices index level (0.22** and 0.15**, respectively) compared to low (21 SD) cultural practices index level (0.16** and 0.06, ns, respectively). Similarly, the indirect effect of the diversity programs index on innovation and organizational performance via absenteeism was stronger at high cultural practices index level (0.15** and 0.16**, respectively) compared to low cultural practices index level (0.04, ns, and 0.10*, respectively). In sumary, this integrative analysis of both our mediation and moderation hypotheses provided additional support for our overall theoretical model (Figure 1) and provided specific estimates of the indirect effect of the diversity program index on innovation and performance (via turnover and absenteeism) at different levels of the moderator variable. Discussion This study addressed three key issues: (1) the effect of national cultural values on the adoption of organizational diversity programs; (2) the moderating effects of national The International Journal of Human Resource Management 897 cultural practices on the relationship between diversity programs and organizational outcomes; and (3) absenteeism and turnover as mediators of the relationship between diversity programs and performance and innovation. With respect to the first issue – national cultural values and adoption of diversity programs – our results reveal that national culture is indeed related to the likelihood that organizations will adopt diversity programs in an effort to increase the employment prospects of women, minorities and potentially disadvantaged groups in the workforce. A particular set of national aspirational values (high individualism, low power distance, low uncertainty avoidance, high future orientation, high gender egalitarianism and high performance orientation) was associated with a greater likelihood that organizations would adopt diversity programs. A straightforward interpretation of this finding is that national cultures that are more open, individualistic, egalitarian and future- and performance-oriented are more favorable toward the prospect of furthering the integration of minorities and other underrepresented groups into the workplace. Concerning the second issue – the moderating effects of cultural practices – our results supported the notion that the level of congruency between organizational diversity programs and national cultural practices is an important contributor to the employee withdrawal behaviors of absenteeism and turnover. This finding is consistent with previous findings comparing the effects of US-based diversity programs under different organizational conditions. Studies have shown that diversity programs are unlikely to produce their intended outcomes (e.g. greater representation of women and minorities in positions of authority) when the prevailing values of employees or managers do not match the values of the organizational leaders who implemented the programs, or when employees’ or managers’ behavior reflects a prevailing noninclusive attitude (e.g. Cox, 1993; Cox & Blake, 1991; Kossek & Lobel, 1996; Mor Barak, 2000, 2005). In such cases, diversity programs and their aims may be acknowledged grudgingly at best, or may elicit passive or even active resistance that can reduce commitment to the organization (e.g. Lynch, 2002, 2005; Mobley & Payne, 1992; Thomas & Plaut, 2008). Such findings are also consistent with Chua’s (2013) recent findings on the effects of intercultural diversity on creativity in organizations. Chua (2013) found that workplaces with high levels of cultural diversity often produce feelings of ‘ambient cultural disharmony’ that can inhibit or disrupt creativity and problem solving within the organization. This disharmony is especially likely when individuals perceive conflict or tension between their own values and those of individuals from different cultures. In our study, differences (lack of fit) between the national culture (essentially the aspirational values) and the values that actually guided practice (the cultural practice values) similarly led to negative outcomes such as higher absenteeism and turnover. Our results extend these findings to the global context, showing that incongruence between the values that support diversity programs and the prevailing cultural practices may have deleterious effects on employee reactions. Concerning the third issue – the role of absenteeism and turnover as mediators of the relationship between diversity programs and performance and innovation – our results help elucidate the process by which diversity programs affect organizational outcomes. To the extent that the values that support diversity programs are in tension with the practices that guide employees’ behavior in the workplace, employees are likely to withdraw psychologically and behaviorally from their organization. This withdrawal is likely to have negative effects on the ‘distal’ variables of performance and innovation. The theoretical and practical contributions of our study are extensive, especially given the significant growth in the global economy. From a theoretical standpoint, the results help advance our understanding of the boundary conditions for the successful adoption of 898 H. Peretz et al. diversity programs in the global environment, in particular as these are influenced by cultural values and practices. The study also supports the distinction between cultural values and cultural practices proposed by the GLOBE studies. Our study supports the notion that cultural values are antecedents to diversity programs, while cultural practices serve as moderators of the effect of diversity programs on organizational outcomes. From a practical standpoint, the study has important implications for organizational performance and competitiveness. Because of increased globalization and the extensiveness of international business operations, corporations would likely benefit from research findings concerning the adoption of diversity programs in different cultures and under different organizational conditions, and their relative effects on important organizational outcomes. The findings enable managers who are responsible for global operations, or who are employed by organizations competing in global markets, to determine more accurately and effectively when to establish diversity programs in organizations that are based in or operating in different countries, so as to improve organizational competitiveness. Moreover, potentially, in the longer run, managers may enhance acceptance of diversity programs in organizations located in nations with cultural values that are less supportive of diversity. Specifically, managers could emphasize a more sustained effort to increase their organizational members’ acceptance of, and appreciation for, diversity and related diversity programs of various kinds. For example, managers could provide evidence from units in their own organization or from other comparable organizations, to illustrate the contribution of diversity and diversity programs to important organizational outcomes (e.g. number of patents, process improvements). Managers might also emphasize the potential contributions of diversity to organizational outcomes in their onboarding or orientation programs, signaling the importance of the values of openness and inclusion. Such an approach has been advocated by Mor Barak (2005) in her analysis of inclusion as a separate and behaviorally oriented dimension related to diversity. As the number of organizations adopting such an approach to diversity increases, it may in the long run bring about a change in the overall value accorded diversity in the larger society (cf. Erez, 2000; Kozlowski, Chao, Grand, Braun, & Kuljanin, 2013). Future research should replicate the study in other countries, as well as expand on its scope. For example, a worthwhile direction for future studies would be to investigate the optimal level of diversity considered effective in different cultures. The key issue here is whether the tipping point at which diversity becomes less effective varies across different cultures. This would have direct implications for the optimal number and type of diversity programs that organizations should adopt. In this context we note that research has shown that stronger diversity programs pursued by affirmative action programs (AAPs) elicit much stronger, and often more polarized, reactions from employees than do weaker AAPs (e.g. Harrison, Kravitz, Mayer, Leslie, & Lev-Arey, 2006; Kravitz & Klineberg, 2000; Levi & Fried, 2008). Future research should also explore, in addition to national culture, the effect of organizational contingencies such as organizational culture or managerial practices (e.g. Donaldson, 2001), on the prevalence of diversity programs and their effects on organizational outcomes. While national culture has been shown to affect organizational culture and organizational practices, (e.g. Kwantes & Dickson, 2011), there are organizations with cultures that do not reflect the national norms or might even depart substantially from these norms (Kwantes & Dickson, 2011). Thus, it would be valuable to study how organizational differences mitigate the effects of national cultures. The study has some potential limitations that should be addressed in future studies. Specifically, some measures (diversity programs, employee withdrawal behaviors of The International Journal of Human Resource Management 899 absenteeism and turnover, and organizational performance) were provided by the same source, although the absenteeism and turnover measures were derived from objective data within the organizations. In addition, while the Cranet data were collected in 2009, the GLOBE data on culture were published in 2004. However, it is likely that cultural values and practices remained stable over this time period (2004 –2009). Finally, the measure of diversity programs provides information on the prevalence of diversity programs, but not on their strength. Future studies could develop and use more detailed measures of diversity program characteristics and strength. We note that countries may differ in the prevalence of diversity programs not only because of their national culture, as we examined in our study, but also because of other factors such as the countries’ legal system, degree of governmental enforcement or economic growth level. For example, in the USA, antidiscrimination laws and strong enforcement of regulations tend to contribute to the prevalence of programs to increase diversity on the basis of race, sex and disability. Nevertheless, even taking these other factors into account, our study supports the importance of national culture in predicting organizations’ adoption of diversity programs. Our findings on cultural values and their effects, as well as our research methods, will likely be applicable in research concerning cross-cultural organizational processes such as globalization, outsourcing and expatriate behavior. In particular, our results confirm the importance of examining the main and interactive contributions of both national- and organizational-level variables. Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Funding This study was funded by a grant from the SHRM Foundation. However, the interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the SHRM Foundation. References Arvey, R. A., McKay, P., Wilson, D., & Tonidandel, S. (2007). Unequal attendance: The relationships between race, organizational diversity cues, and absenteeism. Personnel Psychology, 60, 875– 902. Aycan, Z. (2005). The interplay between cultural and institutional/structural contingencies in human resource management practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 1083– 1119. Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., & Kurshid, A. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49, 192– 221. Aycan, Z., Sinha, J. B. P., & Kanungo, R. N. (1999). Organizational culture and human resource management practices: The model of culture fit. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 501– 526. Baringa, E. (2007). Cultural diversity at work: National culture as a discourse organizing an international project group. Human Relations, 60, 315– 340. Bassett-Jones, N. (2005). The paradox of diversity management, creativity, and innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 14, 169– 175. Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11, 142– 163. 900 H. Peretz et al. Biron, M., & De Reuver, R. (2013). Restoring balance? Status inconsistency, absenteeism, and HRM practices. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22, 683– 696. Bukchin, Y., & Cohen, Y. (2013). Minimising throughput loss in assembly lines due to absenteeism and turnover via work-sharing. International Journal of Production Research, 51, 6140 –6151. Brewster, C., Mayrhofer, W., & Morley, M. (Eds.). (2004). Human resource management in Europe: Evidence of convergence? Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185– 216. Bycio, P. (1992). Job performance and absenteeism: A review and meta-analysis. Human Relations, 45, 193– 221. Chua, R. Y. J. (2013). The costs of ambient cultural disharmony: Indirect intercultural conflicts in social environment undermine creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 1545– 1577. Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Combs, G. M., Nadkarni, S., & Combs, M. W. (2005). Implementing affirmative action plans in multinational corporations. Organizational Dynamics, 34, 346– 360. Cox, T. H. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. Academy of Management Executive, 5, 45 – 56. Cox, T. R., Lobel, S. A., & McLeod, P. A. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 827– 847. Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Hoge, M. (2004). Cross-national differences in managers’ willingness to justify ethically suspect behaviors: A test of institutional anomie theory. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 411– 421. Cunningham, G. B., & Sagas, M. (2004). Examining the main and interactive effects of deep- and surface-level diversity on job satisfaction and organizational turnover intention. Organizational Analysis, 12, 319– 332. Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Ely, R. J. (2004). A field study of group diversity, participation in diversity education programs, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 755– 780. Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12, 121–138. Erez, M. (2000). Make management practice fit the national culture. In E. A. Locke (Ed.), Basic principles of organizational behavior: A handbook (pp. 418– 434). New York, NY: Blackwell. Ferdman, B. M., & Sagiv, L. (2012). Diversity in organizations and cross-cultural work psychology: What if they were more connected? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 5, 323– 345. Fischer, R., Ferreira, M. C., Assmar, E. M. L., Redford, P., & Harb, C. (2005). Organizational behavior across cultures: Theoretical and methodological issues for developing multi-level frameworks involving culture. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 5, 27 – 48. Glebbeek, A. C., & Bax, E. H. (2004). Is high employee turnover really harmful? An empirical test using company records. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 277– 286. Harrison, D. A., Kravitz, D. A., Mayer, D. M., Leslie, L. M., & Lev-Arey, D. (2006). Understanding attitudes toward affirmative action programs in employment: Summary and meta-analysis of 35 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1013– 1036. Hofmann, D. A., & Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24, 623– 641. Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultural constraints in management theories. Academy of Management Executive, 7, 81 – 91. Hofstede, G., & Peterson, M. F. (2000). Culture: National values and organizational practices. Chapter 25. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. P. M. Wilderom, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of organizational culture and climate. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hom, P. W., & Griffeth, R. W. (1995). Employee turnover. Cincinnati, OH: South Western College. Hom, P. W., & Kiniki, A. J. (2001). Toward a greater understanding of how dissatisfaction drives employee turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 975– 987. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 901 Homan, A. C., van Knippenberg, D., Van Kleef, G. A., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2007). Bridging faultiness by valuing diversity: Diversity beliefs, information elaboration, and performance in diverse work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1189– 1199. House, R., Hanges, P, Javidan, M., Dorfman, P., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37, 3– 10. Izraeli, O., & Murphy, K. J. (2003). The effects of industrial diversity on state unemployment rate and per capita income. Annals of Regional Science, 37, 1 – 14. Jackson, S. E., & Joshi, A. (2011). Diversity in social context: A multi-attribute, multilevel analysis of team diversity and sales performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 675– 702. Javidan, M., House, R., Dorfman, P., Hanges, P., & Sully de Luque, M. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 897– 914. Johns, G. (2011). Attendance dynamics at work: The antecedents and correlates of presenteeism, absenteeism, and productivity loss. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 483–500. Jonsen, K., Maznevski, M. L., & Schneider, S. C. (2011). Special review article: Diversity and its not so diverse literature: An international perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 11, 35 – 62. Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71, 589–617. Kim, S. (1999). Globalization of human resource management: A cross-cultural perspective for the public sector. Public Personnel Management, 28, 227–243. Kochan, T. A., Bezrukova, K., Ely, R. J., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., Jehn, K., . . . Thomas, D. A. (2003). The effect of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resources Management, 42, 3 – 21. Kossek, E. E., & Lobel, S. A. (1996). Managing diversity: Human resource strategies for transforming the workplace. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. Kossek, E. E., & Zonia, S. C. (1993). Assessing diversity climate: A field study of reactions to employer efforts to promote diversity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 61 – 81. Kozlowski, S. W. J., Chao, G. T., Grand, J. A., Braun, M. T., & Kuljanin, G. (2013). Advancing multilevel research design: Capturing the dynamics of emergence. Organizational Research Methods, 16, 581– 615. Kravitz, D. A., & Klineberg, S. L. (2000). Reactions to two versions of preferential treatment among whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 579– 611. Kwantes, C. T., & Dickson, M. W. (2011). Organizational culture in a societal context: Lessons from GLOBE and beyond. In N. M. Ashkenasy, C. P. M. Widerom, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of organizational culture and climate (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Levi, A., & Fried, Y. (2008). Differences between African-Americans and whites in reactions to affirmative action programs in hiring, promotion, training, and layoffs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1118 –1129. Lynch, F. R. (2002). The diversity machine: The drive to change the ‘white male workplace’. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Lynch, F. R. (2005). Corporate diversity. Society, 42, 40 – 47. Mannix, E., & Neale, M. A. (2005). What differences make a difference: The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6, 31 – 55. McMahon, A. M. (2010). Does workplace diversity matter? A survey of empirical studies on diversity and firm performance, 2000– 09. Journal of Diversity Management, 5, 37 – 48. Mendonca, M., & Kanungo, R. N. (1994). Managing human resources: The issue of cultural fit. Journal of Management Inquiry, 3, 189– 205. Mobley, M., & Payne, T. (1992). Backlash!: The challenge to diversity training. Training and Development, 46, 45 – 52. Mor Barak, M. E. (2000). Beyond affirmative action: Toward a model of organizational inclusion. In M. E. Mor Barak & D. Bargal (Eds.), Social services in the workplace. New York, NY: Haworth. Mor Barak, M. E. (2005). Managing diversity: Toward a globally inclusive workplace. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 902 H. Peretz et al. Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York, NY: Academic Press. Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. Navrbjerg, S. E., & Minbaeva, D. (2009). HRM and IR in multinational corporations in Denmark: Uneasy bedfellows? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20, 1720– 1736. O’Reilly, C. A., Caldwell, D., & Barnett, W. (1989). Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 21 – 37. Ostergaard, C. R., Timmermans, B., & Kristinsson, K. (2011). Does different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Research Policy, 40, 500– 509. Page, S. E. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Peretz, H., & Fried, Y. (2012). A cross culture examination of performance appraisal and organizational performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 448– 459. Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437– 448. Preacher, K. J., & James, P. S. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6, 77 – 98. Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. Recchia, A. (2010). R-squared measures for two level hierarchical linear models using SAS. Journal of Statistical Software, 32, 1 –9. Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group and Organization Management, 31, 212– 236. Roth, P. L., Huffcutt, A. I., & Bobko, P. (2003). Ethnic group differences in measures of job performance: A new meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 694– 706. Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 1– 13. Ryan, A. M., McFarland, L. A., Baron, H., & Page, R. (1999). An international look at selection practices: Nation and culture as sources of variability in practice. Personnel Psychology, 52, 359– 391. Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology, 48, 23 – 47. Shen, J., Chanda, A., D’Netto, B., & Monga, M. (2009). Managing diversity through human resource management: An international perspective and conceptual framework. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20, 235– 251. Sieben, I. (2007). Does training trigger turnover-or not? The impact of formal training on graduates’ job search behavior. Work, Employment & Society, 21, 397– 416. Simon, C., & Nardinelli, C. (1992). Does industrial diversity always reduce unemployment? Evidence from the Great Depression and after. Economic Inquiry, 30, 384– 397. Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage. Somers, M. J. (1995). Organizational commitment, turnover, and absenteeism: An examination of direct and interaction effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 49 – 58. Sowell, T. (2004). Affirmative action around the world: An empirical study. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Stahl, G., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. (2010). Unravelling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 690– 709. Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomas, D. A., & Ely, R. J. (1996). Making differences matter: A new paradigm for managing diversity. Harvard Business Review, 96, 79 –90. Thomas, K. M., & Plaut, V. C. (2008). The many faces of diversity resistance in the workplace. In K. M. Thomas (Ed.), Diversity resistance in organizations (pp. 1 – 22). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 903 Triandis, H. C. (1994). Cross cultural industrial and organizational psychology. In H. C. Triandis, M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 4, 2nd ed., pp. 103– 172). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Turner, J. C. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. van Knippenberg, D., & Schippers, M. C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 5151 –5541. Watson, W. E., Kumar, K., & Michaelsen, L. K. (1993). Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 590– 602. Westwood, R., & Low, D. R. (2003). The multicultural muse: Culture creativity and innovation. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 3, 235– 258. Whitely, W. T., & Coestier, P. (1993). The relationship of career mentoring to early career outcomes. Organizational Studies, 14, 419– 441. Wood, P. (2003). Diversity: The invention of a concept. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books. Ybema, J. F., Smulders, P. G. W., & Bongers, P. M. (2010). Antecedents and consequences of employee absenteeism: A longitudinal perspective on the role of job satisfaction and burnout. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19, 102– 124. Copyright of International Journal of Human Resource Management is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.