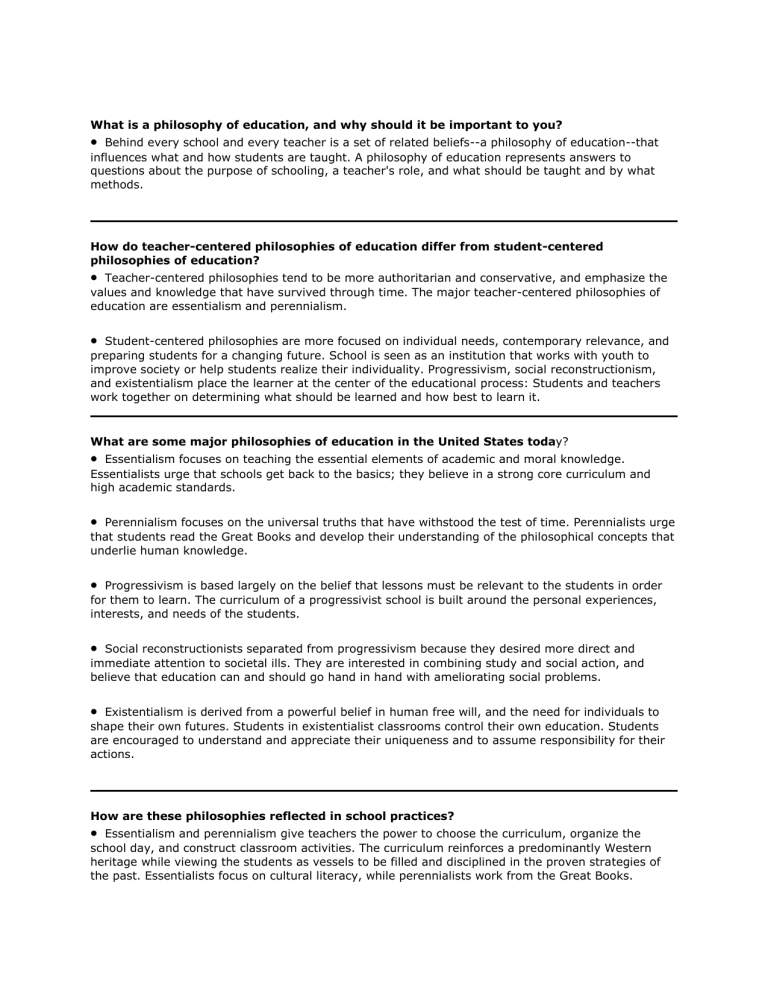

What is a philosophy of education, and why should it be important to you? Behind every school and every teacher is a set of related beliefs--a philosophy of education--that influences what and how students are taught. A philosophy of education represents answers to questions about the purpose of schooling, a teacher's role, and what should be taught and by what methods. How do teacher-centered philosophies of education differ from student-centered philosophies of education? Teacher-centered philosophies tend to be more authoritarian and conservative, and emphasize the values and knowledge that have survived through time. The major teacher-centered philosophies of education are essentialism and perennialism. Student-centered philosophies are more focused on individual needs, contemporary relevance, and preparing students for a changing future. School is seen as an institution that works with youth to improve society or help students realize their individuality. Progressivism, social reconstructionism, and existentialism place the learner at the center of the educational process: Students and teachers work together on determining what should be learned and how best to learn it. What are some major philosophies of education in the United States today? Essentialism focuses on teaching the essential elements of academic and moral knowledge. Essentialists urge that schools get back to the basics; they believe in a strong core curriculum and high academic standards. Perennialism focuses on the universal truths that have withstood the test of time. Perennialists urge that students read the Great Books and develop their understanding of the philosophical concepts that underlie human knowledge. Progressivism is based largely on the belief that lessons must be relevant to the students in order for them to learn. The curriculum of a progressivist school is built around the personal experiences, interests, and needs of the students. Social reconstructionists separated from progressivism because they desired more direct and immediate attention to societal ills. They are interested in combining study and social action, and believe that education can and should go hand in hand with ameliorating social problems. Existentialism is derived from a powerful belief in human free will, and the need for individuals to shape their own futures. Students in existentialist classrooms control their own education. Students are encouraged to understand and appreciate their uniqueness and to assume responsibility for their actions. How are these philosophies reflected in school practices? Essentialism and perennialism give teachers the power to choose the curriculum, organize the school day, and construct classroom activities. The curriculum reinforces a predominantly Western heritage while viewing the students as vessels to be filled and disciplined in the proven strategies of the past. Essentialists focus on cultural literacy, while perennialists work from the Great Books. Progressivism, social reconstructionism, and existentialism view the learner as the central focus of classroom activities. Working with student interests and needs, teachers serve as guides and facilitators in assisting students to reach their goals. The emphasis is on the future, and on preparing students to be independent-thinking adults. Progressivists strive for relevant, hands-on learning. Social reconstructionists want students to actively work to improve society. Existentialists give students complete freedom, and complete responsibility, with regard to their education. What are some of the psychological and cultural factors influencing education? Constructivism has its roots in cognitive psychology, and is based on the idea that people construct their understanding of the world. Constructivist teachers gauge a student's prior knowledge, then carefully orchestrate cues, classroom activities, and penetrating questions to push students to higher levels of understanding. B. F. Skinner advocated behaviorism as an effective teaching strategy. According to Skinner, rewards motivate students to learn material even if they do not fully understand why it will have value in their futures. Behavior modification is a system of gradually lessening extrinsic rewards. The practices and beliefs of peoples in other parts of the world, such as informal and oral education, offer useful insights for enhancing our own educational practices, but they are insights too rarely considered, much less implemented. What were the contributions of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to Western philosophy, and how are their legacies reflected in education today? Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the three most legendary ancient Greek philosophers. Socrates is hailed today as the personification of wisdom and the philosophical life. He gave rise to what is now called the Socratic method, in which the teacher repeatedly questions students to help them clarify their own deepest thoughts. Plato, Socrates's pupil, crafted eloquent dialogues that present different philosophical positions on a number of profound questions. Plato believed that a realm of externally existing"ideas," or"forms," underlies the physical world. Aristotle, Plato's pupil, was remarkable for the breadth as well as the depth of his knowledge. He provided a synthesis of Plato's belief in the universal, spiritual forms and a scie PHILIPPINE EDUCATION: ISSUES AND CONCERNS Let us first identify the important issues affecting the Philippine educational system. The first issue is the role of education in national development. Several researchers had delved into the different components affecting the educational system, more specifically, whether it can solve the multifarious problems in society. Education has been looked into as the means of alleviating poverty, decreasing criminalities, increasing economic benefits and ultimately uplifting the standard of living of the Filipino masses. With these in mind, the government on its part has been continuously investing so much resource into the education sector. However, with the complexity of educational issues, solutions are far from reality. Allied with this issue is the preparation of our students from the basic education up to tertiary level. The questions of how well are the schools equipped and able to train the pupils under their care are crucial. It is a sad reality that only seven out of ten pupils who enroll in Grade 1 finish the elementary curriculum, and from the seven who continue to secondary, only 3 are able to complete the curriculum. From these three only one can complete the tertiary education. Based on this scenario, how can we expect our students to help in nation building when they do not have the necessary skills and trainings? Reality is that, formal education has not achieved what it was supposed to achieve. Our schools right now are in a quandary on how to keep children in school, with the increasing rate of drop outs. The functional literacy of the Filipinos is at its minimum reflecting the sad state of education. There are rampant problems of child labor, where children who are supposed to be in the classroom are working to help augment family income. Unemployment rate is rising every year as more students graduate from colleges and universities, who cannot be accommodated by the labor market. Underemployment is the name of the game since professionals are forced to accept employment far from their areas of specialization and training because they need to work and earn for their families. The gap between the few who are rich and the majority who are poor is becoming wider and bigger. Now what has education got to do with this? If experts claimed that education is an instrument for national development, where does the problem lie? Another important issue confronting the educational system is the curriculum that is not responsive to the basic needs of the country. Let us reflect on the components of the present アシエン ヅロナル オホ ソセアル サイネセズ アナド ヒウメニテズ ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 1. No. 2. May 2012 (株) リナ&ルナインターナショナル 小山市、日本. www. leena-luna.co.jp P a g e | 66 curriculum, specifically in the basic education. Our elementary pupils are required to have nine to ten subjects competing for time allocations. More time is allotted for subjects like English, Science and Mathematics with other subjects like health, music, values education, civics integrated into the Makabayan curriculum. Added to this are enrichment subjects like Computer literacy, Ethics among others (especially in the private schools). This reflects the priorities of the government in educating our young people. It is a reality that a grade 1 pupil carries so many books to school (wondering whether all these materials are actually read in the class). This overloaded curriculum results to difficulty in knowledge and skills absorption among our pupils. With this practice how can we expect our young people to develop love of country, patriotism, and other nationalistic traits, when their concepts of these are not properly taught? Worse, many pupils drop out of school before they reach the sixth grade because of poverty, thus increasing their chances of losing the incipient literacy acquired, and therefore, forfeit the privilege of developing patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. This sad state, proliferate the cycle of poverty that the Filipino masses experience. With the constant change in the basic education curriculum, teachers need to upgrade themselves in order that they can properly implement these changes. Upgrading requires attendance to trainings, seminars, conferences and even enrollment in graduate education. But with the present conditions of the teachers in the public schools only very few can afford this, unless government intervenes and provide upgrading activities for free. Another issue that is of import is the constant implementation of programs in education which are not properly monitored. It is a fact that technocrats in the education department are political appointees, hence they serve at the whims and pleasures of the appointing officer. It is also a fact that every political administration wanted to have their names imprinted in every government program or project. This is very true in the Department of Education, when for instance, a department secretary appointed by a particular president assumes office, he will be implementing programs and projects attuned to the battlecry of that administration. Therefore, the previous programs and projects implemented by the previous administration shall be discontinued, regardless that program or project is workable and effective, because it is not the priority of the present administration, and does not carry their names. Added to that is the non evaluation of programs implemented. A very concrete example is the Bridge program implemented a few years ago. This program screens grade six pupils by subjecting them to testing. Those who were not able to pass were required to repeat grade six as a bridge for their secondary education. As a result, many pupils were required to re enroll in grade 6, adding a year to their elementary education. But, after many complaints and criticisms, this program was discontinued. But what about the losses incurred by the department? The added year in the academic life of the pupils affected? The added financial burden to parents? Who will answer and be accountable for this blunder? Is this just a case of trial and error program implementation? Presumably, the program was not properly studied, but was only implemented to satisfy the egos of the technocrats in the education department. Anent to these issues are concerns that the education sector have to address. First concern is the socalled globalization of education. This concern was a response to the ever changing milieu in the international academic community where students must be globally competitive. Thus, schools must transform their orientation from being parochial to liberal. Programs must be re ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 1. No. 2. May 2012 ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES www.ajssh.leena-luna.co.jp 67 | P a g e Leena and Luna International, Oyama, Japan. Copyright © 2012 aligned to meet international standards. Qualifications of teachers, facilities of the institutions and instructional materials and strategies must conform with international accreditation requirements. But how many of our institutions, are able to meet this requirement? Tertiary institutions continue to produce graduates who do not have the necessary employability skills, not only in terms of the local norms but more so with international standards. Sadly, even if our graduates work abroad they end up working as laborers, domestics and other blue collar workers which do not fit their educational credentials. I believe, that you will agree with me that is this not the concept of globalization we have in mind. The Department of Education will implement the K-12 program by the next school year. This is in response to the alignment of the basic education curriculum to international standards. The present system of 6 – 4 – 4, according to the education experts lacks the required number of years that our students have to spend in school, from the elementary, secondary up to the tertiary level. Hence, there is a need to add two more years to our basic education so that the students will have more years in developing the necessary employability skills they must have after they graduate from secondary school. But is this really the answer to the present handicap of our educational system? Will adding two years bring more benefits? Or will it just result to more financial implications, not only to the parents but also to the government? This is a concern that has to be addressed before it becomes too late for us to realize the impact it will create in the succeeding years. The educational system does not receive much budget from the government. This resulted to poor facilities. Schools in the rural areas do not receive much support from the government. School supplies such as books are received by them almost at the end of the year. What use will it give the pupils and students? To add more insult, textbooks contain a lot of errors in spelling and facts presented. This is a clear indication of a government’s failure to provide the basic services needed by its people. The same problem is also experienced by State Universities and College when the government decided to reduce their budget allocation. News reports of students from the University of the Philippines and other State Universities picketing before Congress demanding for the increase of their budget is not a rare scenario. Students took it upon themselves to ventilate school budget concerns for these can redound to increase in their matriculation fees, non- upgrading or updating of school and library facilities, and non hiring of additional faculty members, among others. State run institutions are empowered to generate their income in order that they can manage their finances and not depend so much from government subsidies. It is in this context that school administrators do their best to win favors from politicians, whom they believe can support their school programs and projects. This results to another concern of too much politics in education. Politics in education is an issue that presently pervades educational system in the country. The government, specifically the legislators, is inept in formulating laws that can address the crisis in the educational system. A sad reality that is happening right now is the formulation of policies with the main purpose of making our educational system at par with those in other countries, but there are no concrete guidelines as to how these are to be implemented. Most educational experts are technocrats with no experience in the field. Yes, their programs are good, to say the アシエン ヅロナル オホ ソセアル サイネセズ アナド ヒウメニテズ ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 1. No. 2. May 2012 (株) リナ&ルナインターナショナル 小山市、日本. www. leena-luna.co.jp P a g e | 68 least, but because of their lack of experience in actual classroom teaching, they fail to study the application of these programs. One specific example is the Bridge Program that was implemented a few years ago. This program assessed the competency of Grade Six pupils to be promoted to High School. There were grade six pupils who scored below the passing mark that were made to repeat grade six to bridge their admission to high school. Thus, this added another year of elementary schooling. However, after a year of its implementation, the program was stopped. Worst, teachers in the classrooms were not duly informed of the reasons for its noncontinuance. This is just one of the many educational programs implemented in the Philippine educational system that were not properly monitored and evaluated. This brings to a conclusion that Filipinos are only good planners but not good implementers and evaluators. Undeniably, administrators of state run institutions solicit financial support from politicians who can sustain their school projects. There is nothing wrong with this. However, if the support given by politician must be equated by some favors from school officials, this becomes a major concern by everybody. There are cases where principals, supervisors and even superintendent of schools and divisions are appointed because they are recommended by well known senators, congressmen, governors and even mayors. This practice extends even up to the lowest level. Politicians recommend their relatives to be hired as teachers and other school staff. And if the principal has some debt of gratitude to the politician because of the support he is giving to the school, his recommendation cannot be refused. This practice defeats the purpose of screening applicants for teaching positions because even if you are first in the ranking, but you do not have a political back up, you will be the least priority in hiring. Although we cannot totally separate politics in education, it is of great import that objectivity, fairness and justice must be observed. It is very ironic that schemes like these happen in an institution that is expected to teach and inculcate good moral values and virtues among the young people of Philippine society. As educators, what then can we do to transform the image that the educational system had propagated through the years? As an educator, I believe that total transformation must be implemented in the education sector of the country. When I say transformation of the education sector I refer to the total re orientation of the system which would start from policy transformation. Education policies and programs, including the curriculum must be carefully evaluated and studied whether they are attuned to the needs of the people and the country. Review of the provisions must be done in all levels and participation of the stakeholders must be solicited. Experts must be realistic in coming up with more attainable policies, that will address not only the educational problems but more so contribute to economic growth and development of the country. I also believe in the values reorientation of the Filipinos as a key to national development. The integration of values education in the curriculum, I believe is still not enough to address this need. Values become more permanent in the minds and hearts of the pupils and students when they are caught, modeled by their mentors, rather than being discussed as abstract concepts in the classrooms. Thus, there is an urgent call for teacher transformation, in terms of their values orientation. I believe that teachers cannot become effective models of good moral values unless they undergo some process of values transformation. It is always wise to say “follow what I say and do,” rather than “follow what I say, do not follow what I do.” It is only when pupils and students concretely observe their teachers consistently practice these good values that they will ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 1. No. 2. May 2012 ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES www.ajssh.leena-luna.co.jp 69 | P a g e Leena and Luna International, Oyama, Japan. Copyright © 2012 be able to replicate these in themselves. These, I believe is easier said than done. But unless we start doing it, we cannot claim tried. Lastly, I believe that teachers’ transformation must include their upgrading or updating for professional and personal development. Even if the salary of the ordinary public school teacher had been standardized to be competitive, with the increasing economic crisis, it will still be not enough to afford them attendance to seminars, trainings and enrollment in graduate education. Hence, government support and intervention, along this line is very much needed. Our teachers are professionals, and I believe their pre-service training had equipped them with the necessary skills to teach. Yet, with the advancement in science and technology, there is a great need for them to acquire competence in the use of these state of the art equipments to enhance their teaching skills. The government must invest on our teachers because it is through them that we train and develop the minds of our future leaders. As they say, show me your schools and I will tell you what society you will have. REFERENCES Apilado, Digna (2008). A History of Paradox: Some Notes on Philippine Public Education in the 20th Century. Barrows, David (1910). What May Be Expected from Philippine Education?, The Journal of Pre-Socratic Philosophy Back to Top Western Philosophy - by which we usually mean everything apart from the Eastern Philosophy of China, India, Japan, Persia, etc - really began in Ancient Greece in about the 6th Century B.C. Thales of Miletus is usually considered the first proper philosopher, although he was just as concerned with natural philosophy (what we now call science) as with philosophy as we know it. Thales and most of the other Pre-Socratic philosophers (i.e. those who lived before Socrates) limited themselves in the main toMetaphysics (enquiry into the nature of existence, being and the world). They were Materialists (they believed that all things are composed of material and nothing else) and were mainly concerned with trying to establish the single underlying substance the world is made up of (a kind of Monism), without resorting to supernatural or mythological explanations. For instance, Thales thought the whole universe was composed of different forms of water; Amaximenes concluded it was was made of air; Heraclitus thought it was fire; and Anaximander some unexplainable substance usually translated as "the infinite" or "the boundless". Another issue the Pre-Socratics wrestled with was the so-called problem of change, how things appear to change from one form to another. At the extremes, Heraclitus believed in an on-going process of perpetual change, a constant interplay ofopposites; Parmenides, on the other hand, using a complicated deductive argument, denied that there was any such thing as change at all, and argued that everything that exists is permanent, indestructible and unchanging. This might sound like an unlikely proposition, but Parmenides's challenge was well-argued and was important in encouraging other philosophers to come up with convincing counter-arguments. Zeno of Elea was a student of Parmenides, and is best known for his famousparadoxes of motion (the best known of which is that of the Achilles and the Hare), which helped to lay the foundations for the study of Logic. However, Zeno's underlying intention was really to show, like Parmenides before him, that all belief in pluralityand change is mistaken, and in particular that motion is nothing but an illusion. Although these ideas might seem to us rather simplistic and unconvincing today, we should bear in mind that, at this time, there was really no scientific knowledge whatsoever, and even the commonest of phenomena (e.g. lightning, water freezing to ice, etc) would have appeared miraculous. Their attempts were therefore important first steps in the development of philosophical thought. They also set the stage for two other important Pre-Socratic philosophers: Empedocles, who combined their ideas into the theory of the four classical elements (earth, air, fire and water), which became the standard dogma for much of the next two thousand years; and Democritus, who developed the extremely influential idea of Atomism (that all of reality is actually composed of tiny, indivisible and indestructible building blocks known as atoms, which form different combinations and shapes within the surrounding void). Another early and very influential Greek philosopher was Pythagoras, who led a rather bizarre religious sect and essentially believed that all of reality was governed by numbers, and that its essence could be encountered through the study ofmathematics. Classical Philosophy Back to Top Philosophy really took off, though, with Socrates and Plato in the 5th - 4th Century B.C. (often referred to as the Classical orSocratic period of philosophy).Unlike most of the Pre-Socratic philosophers before him, Socrates was more concerned with how people should behave, and so was perhaps the first major philosopher of Ethics. He developed a system of critical reasoning in order to work out how to live properly and to tell the difference between right and wrong. His system, sometimes referred to as the Socratic Method, was to break problems down into a series of questions, the answers to which would gradually distill a solution. Although he was careful to claim not to have all the answers himself, his constant questioning made him many enemies among the authorities of Athens who eventually had him put to death. Socrates himself never wrote anything down, and what we know of his views comes from the "Dialogues" of his student Plato, perhaps the best known, most widely studied and most influential philosopher of all time. In his writings, Plato blendedEthics, Metaphysics, Political Philosophy and Epistemology (the theory of knowledge and how we can acquire it) into aninterconnected and systematic philosophy. He provided the first real opposition to the Materialism of the Pre-Socratics, and he developed doctrines such as Platonic Realism, Essentialism and Idealism, including his important and famous theory of Formsand universals (he believed that the world we perceive around us is composed of mere representations or instances of the pure ideal Forms, which had their own existence elsewhere, an idea known as Platonic Realism). Plato believed that virtue was a kind of knowledge (the knowledge of good and evil) that we need in order to reach the ultimate good, which is the aim of all human desires and actions (a theory known as Eudaimonism). Plato's Political Philosophy was developed mainly in his famous"Republic", where he describes an ideal (though rather grim and anti-democratic) society composed of Workers and Warriors, ruled over by wise Philosopher Kings. The third in the main trio of classical philosophers was Plato's student Aristotle. He created an even more comprehensive system of philosophy than Plato, encompassing Ethics, Aesthetics, Politics, Metaphysics, Logic and science, and his work influenced almost all later philosophical thinking, particularly those of the Medieval period. Aristotle's system of deductive Logic, with its emphasis on the syllogism (where a conclusion, or synthesis, is inferred from two other premises, the thesis andantithesis), remained the dominant form of Logic until the 19th Century. Unlike Plato, Aristotle held that Form and Matter wereinseparable, and cannot exist apart from each other. Although he too believed in a kind of Eudaimonism, Aristotle realized thatEthics is a complex concept and that we cannot always control our own moral environment. He thought that happiness could best be achieved by living a balanced life and avoiding excess by pursuing a golden mean in everything (similar to his formula for political stability through steering a middle course between tyranny and democracy). Other Ancient Philosophical Schools Back to Top In the philosophical cauldron of Ancient Greece, though (as well as the Hellenistic and Roman civilizations which followed it over the next few centuries), several other schools or movements also held sway, in addition to Platonism and Aristotelianism: Sophism (the best known proponents being Protagoras and Gorgias), which held generally relativistic views on knowledge (i.e. that there is no absolute truth and two points of view can be acceptable at the same time) and generally skepticalviews on truth and morality (although, over time, Sophism came to denote a class of itinerant intellectuals who taught courses in rhetoric and "excellence" or "virtue" for money). Cynicism, which rejected all conventional desires for health, wealth, power and fame, and advocated a life free from allpossessions and property as the way to achieving Virtue (a life best exemplified by its most famous proponent,Diogenes). Skepticism (also known as Pyrrhonism after the movement's founder, Pyrrho), which held that, because we can never know the true innner substance of things, only how they appear to us (and therefore we can never know which opinions are right or wrong), we should suspend judgement on everything as the only way of achieving inner peace. Epicureanism (named for its founder Epicurus), whose main goal was to attain happiness and tranquility through leading a simple, moderate life, the cultivation of friendships and the limiting of desires (quite contrary to the common perception of the word "epicurean"). Hedonism, which held that pleasure is the most important pursuit of mankind, and that we should always act so as tomaximize our own pleasure. Stoicism (developed by Zeno of Citium, and later espoused by Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius), which taught selfcontroland fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions in order to develop clear judgment and inner calm and the ultimate goal of freedom from suffering. Neo-Platonism (developed out of Plato's work, largely by Plotinus), which was a largely religious philosophy which became a strong influence on early Christianity (especially on St. Augustine), and taught the existence of an ineffable and transcendent One, from which the rest of the universe "emanates" as a sequence of lesser beings. Medieval Philosophy Back to Top After about the 4th or 5th Century A.D., Europe entered the so-called Dark Ages, during which little or no new thought was developed. By the 11th Century, though, there was a renewed flowering of thought, both in Christian Europe and in Muslimand Jewish Middle East. Most of the philosophers of this time were mainly concerned with proving the existence of God and with reconciling Christianity/Islam with the classical philosophy of Greece (particularly Aristotelianism). This period also saw the establishment of the first universities, which was an important factor in the subsequent development of philosophy. Among the great Islamic philosophers of the Medieval period were Avicenna (11th century, Persian) and Averröes (12th century, Spanish/Arabic). Avicenna tried to reconcile the rational philosophy of Aristotelianism and NeoPlatonism with Islamic theology, and also developed his own system of Logic, known as Avicennian Logic. He also introduced the concept of the"tabula rasa" (the idea that humans are born with no innate or built-in mental content), which strongly influenced laterEmpiricists like John Locke. Averröes's translations and commentaries on Aristotle (whose works had been largely lost by this time) had a profound impact on the Scholastic movement in Europe, and he claimed that Avicenna's interpretations were adistortion of genuine Aristotelianism. The Jewish philosopher Maimonides also attempted the same reconciliation of Aristotlewith the Hebrew scriptures around the same time. The Medieval Christian philosophers were all part of a movement called Scholasticism which tried to combine Logic,Metaphysics, Epistemology and semantics (the theory of meaning) into one discipline, and to reconcile the philosophy of the ancient classical philosophers (particularly Aristotle) with Christian theology. The Scholastic method was to thoroughly andcritically read the works of renowned scholars, note down any disagreements and points of contention, and then resolve them by the use of formal Logic and analysis of language. Scholasticism in general is often criticized for spending too much time discussing infinitesimal and pedantic details (like how many angels could dance on the tip of a needle, etc). St. Anselm (best known as the originator of the Ontological Argument for the existence of God by abstract reasoning alone) is often regarded as the first of the Scholastics, and St. Thomas Aquinas (known for his five rational proofs for the existence of God, and his definition of the cardinal virtues and the theological virtues) is generally considered the greatest, and certainly had the greatest influence on the theology of the Catholic Church. Other important Scholastics included Peter Abelard, Albertus Magnus, John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham. Each contributed slight variations to the same general beliefs - Abelardintroduced the doctrine of limbo for unbaptised babies; Scotus rejected the distinction between essence and existence thatAquinas had insisted on; Ockham introduced the important methodological principle known as Ockham's Razor, that one should not multiply arguments beyond the necessary; etc. Roger Bacon was something of an exception, and actually criticized the prevailing Scholastic system, based as it was ontradition and scriptural authority. He is sometimes credited as one of the earliest European advocates of Empiricism (the theory that the origin of all knowledge is sense experience) and of the modern scientific method. The revival of classical civilization and learning in the 15th and 16th Century known as the Renaissance brought theMedieval period to a close. It was marked by a movement away from religion and medieval Scholasticism and towardsHumanism (the belief that humans can solve their own problems through reliance on reason and the scientific method) and a new sense of critical enquiry. Among the major philosophical figures of the Renaissance were: Erasmus (who attacked many of the traditions of the Catholic Church and popular superstitions, and became the intellectual father of the European Reformation); Machiavelli (whose cynical and devious Political Philosophy has become notorious); Thomas More (the Christian Humanist whose book "Utopia" influenced generations of politicians and planners and even the early development of Socialist ideas); and Francis Bacon (whose empiricistbelief that truth requires evidence from the real world, and whose application of inductive reasoning - generalizations based on individual instances - were both influential in the development of modern scientific methodology). Early Modern Philosophy Back to Top The Age of Reason of the 17th Century and the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th Century (very roughly speaking), along with the advances in science, the growth of religious tolerance and the rise of liberalism which went with them, mark the real beginnings of modern philosophy. In large part, the period can be seen as an ongoing battle between two opposing doctrines,Rationalism (the belief that all knowledge arises from intellectual and deductive reason, rather than from the senses) andEmpiricism (the belief that the origin of all knowledge is sense experience). This revolution in philosophical thought was sparked by the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, the first figure in the loose movement known as Rationalism, and much of subsequent Western philosophy can be seen as a response to his ideas. His method (known as methodological skepticism, although its aim was actually to dispel Skepticism and arrive atcertain knowledge), was to shuck off everything about which there could be even a suspicion of doubt (including the unreliable senses, even his own body which could be merely an illusion) to arrive at the single indubitable principle that he possessedconsciousness and was able to think ("I think, therefore I am"). He then argued (rather unsatisfactorily, some would say) that our perception of the world around us must be created for us by God. He saw the human body as a kind of machine that follows the mechanical laws of physics, while the mind (or consciousness) was a quite separate entity, not subject to the laws of physics, which is only able to influence the body and deal with the outside world by a kind of mysterious two-way interaction. This idea, known as Dualism (or, more specifically, Cartesian Dualism), set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the "mind-body problem" for centuries after. Despite Descartes' innovation and boldness, he was a product of his times and never abandoned the traditional idea of a God, which he saw as the one true substance from which everything else was made. The second great figure of Rationalism was the Dutchman Baruch Spinoza, although his conception of the world was quite different from that of Descartes. He built up a strikingly original self-contained metaphysical system in which he rejectedDescartes' Dualism in favour of a kind of Monism where mind and body were just two different aspects of a single underlying substance which might be called Nature (and which he also equated with a God of infinitely many attributes, effectively a kind of Pantheism). Spinoza was a thoroughgoing Determinist who believed that absolutely everything (even human behaviour) occurs through the operation of necessity, leaving absolutely no room for free will and spontaneity. He also took the Moral Relativist position that nothing can be in itself either good or bad, except to the extent that it is subjectively perceived to be so by the individual (and, anyway, in an ordered deterministic world, the very concepts of Good and Evil can have little or no absolute meaning). The third great Rationalist was the German Gottfried Leibniz. In order to overcome what he saw as drawbacks and inconsistencies in the theories of Descartes and Spinoza, he devised a rather eccentric metaphysical theory of monadsoperating according to a pre-established divine harmony. According to Leibniz's theory, the real world is actually composed of eternal, non-material and mutually-independent elements he called monads, and the material world that we see and touch is actually just phenomena (appearances or by-products of the underlying real world). The apparent harmony prevailing among monads arises because of the will of God (the supreme monad) who arranges everything in the world in a deterministic manner.Leibniz also saw this as overcoming the problematic interaction between mind and matter arising in Descartes' system, and he declared that this must be the best possible world, simply because it was created and determined by a perfect God. He is also considered perhaps the most important logician between Aristotle and the mid-19th Century developments in modern formalLogic. Another important 17th Century French Rationalist (although perhaps of the second order) was Nicolas Malebranche, who was a follower of Descartes in that he believed that humans attain knowledge through ideas or immaterial representations in the mind. However, Malebranche argued (more or less following St. Augustine) that all ideas actually exist only in God, and that God was the only active power. Thus, he believed that what appears to be "interaction" between body and mind is actually caused by God, but in such a way that similar movements in the body will "occasion" similar ideas in the mind, an idea he calledOccasionalism. In opposition to the continental European Rationalism movement was the equally loose movement of British Empiricism, which was also represented by three main proponents. The first of the British Empiricists was John Locke. He argued that all of our ideas, whether simple or complex, are ultimatelyderived from experience, so that the knowledge of which we are capable is therefore severely limited both in its scope and in its certainty (a kind of modified Skepticism), especially given that the real inner natures of things derive from what he called their primary qualities which we can never experience and so never know. Locke, like Avicenna before him, believed that the mind was a tabula rasa (or blank slate) and that people are born without innate ideas, although he did believe that humans have absolute natural rights which are inherent in the nature of Ethics. Along with Hobbes and Rousseau, he was one of theoriginators of Contractarianism (or Social Contract Theory), which formed the theoretical underpinning for democracy,republicanism, Liberalism and Libertarianism, and his political views influenced both the American and French Revolutions. The next of the British Empiricists chronologically was Bishop George Berkeley, although his Empiricism was of a much moreradical kind, mixed with a twist of Idealism. Using dense but cogent arguments, he developed the rather counterintuitive system known as Immaterialism (or sometimes as Subjective Idealism), which held that underlying reality consists exclusively of minds and their ideas, and that individuals can only directly know these ideas or perceptions (although not the objects themselves) through experience. Thus, according to Berkeley's theory, an object only really exists if someone is there to see orsense it ("to be is to be perceived"), although, he added, the infinite mind of God perceives everything all the time, and so in this respect the objects continue to exist. The third, and perhaps greatest, of the British Empiricists was David Hume. He believed strongly that human experience is as close are we are ever going to get to the truth, and that experience and observation must be the foundations of any logical argument. Hume argued that, although we may form beliefs and make inductive inferences about things outside our experience (by means of instinct, imagination and custom), they cannot be conclusively established by reason and we should not make any claims to certain knowledge about them (a hard-line attitude verging on complete Skepticism). Although he never openly declared himself an atheist, he found the idea of a God effectively nonsensensical, given that there is no way of arriving at the idea through sensory data. He attacked many of the basic assumptions of religion, and gave many of the classic criticisms of some of the arguments for the existence of God (particularly the teleological argument). In his Political Philosophy, Humestressed the importance of moderation, and his work contains elements of both Conservatism and Liberalism. Among the "non-aligned" philosophers of the period (many of whom were most active in the area of Political Philosophy) were the following: Thomas Hobbes, who described in his famous book "Leviathon" how the natural state of mankind was brute-like and poor, and how the modern state was a kind of "social contract" (Contractarianism) whereby individuals deliberately give up their natural rights for the sake of protection by the state (accepting, according to Hobbes, any abuses of power as the price of peace, which some have seen as a justification for authoritarianism and even Totalitarianism); Blaise Pascal, a confirmed Fideist (the view that religious belief depends wholly on faith or revelation, rather than reason, intellect or natural theology) who opposed both Rationalism and Empiricism as being insufficient for determining major truths; Voltaire, an indefatigable fighter for social reform thoughout his life, but wholly cynical of most philosophies of the day, from Leibniz's optimism to Pascal's pessimism, and from Catholic dogma to French political institutions; Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose discussion of inequality and whose theory of the popular will and society as a social contract entered into for the mutual benefit of all (Contractarianism) strongly influenced the French Revolution and the subsequent development of Liberal, Conservative and even Socialist theory; Adam Smith, widely cited as the father of modern economics, whose metaphor of the "invisible hand" of the free market (the apparent benefits to society of people behaving in their own interests) and whose book "The Wealth of Nations" had a huge influence on the development of modern Capitalism, Liberalism and Individualism; and Edmund Burke, considered one of the founding fathers of modern Conservatism and Liberalism, although he also produced perhaps the first serious defence of Anarchism. Towards the end of the Age of Enlightenment, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant caused another paradign shift as important as that of Descartes 150 years earlier, and in many ways this marks the shift to Modern philosophy. He sought to move philosophy beyond the debate between Rationalism and Empiricism, and he attempted to combine those two apparently contradictory doctrines into one overarching system. A whole movement (Kantianism) developed in the wake of his work, and most of the subsequent history of philosophy can be seen as responses, in one way or another, to his ideas. Kant showed that Empiricism and Rationalism could be combined and that statements were possible that were both synthetic(a posteriori knowledge from experience alone, as in Empiricism) but also a priori (from reason alone, as in Rationalism). Thus, without the senses we could not become aware of any object, but without understanding and reason we could not form anyconception of it. However, our senses can only tell us about the appearance of a thing (phenomenon) and not the "thing-in-itself" (noumenon), which Kant believed was essentially unknowable, although we have certain innate predispositions as to what exists (Transcendental Idealism). Kant's major contribution to Ethics was the theory of the Categorical Imperative, that we should act only in such a way that we would want our actions to become a universal law, applicable to everyone in a similar situation (Moral Universalism) and that we should treat other individuals as ends in themselves, not as mere means (Moral Absolutism), even if that means sacrificing the greater good. Kant believed that any attempts to prove God's existence are just a waste of time, because our concepts only work properly in the empirical world (which God is above and beyond), although he also argued that it was not irrational to believe in something that clearly cannot be proven either way (Fideism). 19th Century Philosophy Back to Top In the Modern period, Kantianism gave rise to the German Idealists, each of whom had their own interpretations of Kant's ideas.Johann Fichte, for example, rejected Kant's separation of "things in themselves" and things "as they appear to us" (which he saw as an invitation to Skepticism), although he did accept that consciousness of the self depends on the existence of something that is not part of the self (his famous "I / not-I" distinction). Fichte's later Political Philosophy also contributed to the rise of German Nationalism. Friedrich Schelling developed a unique form of Idealism known as Aesthetic Idealism (in which he argued that only art was able to harmonize and sublimate the contradictions between subjectivity and objectivity, freedom and necessity, etc), and also tried to establish a connection or synthesis between his conceptions of nature and spirit. Arthur Schopenhauer is also usually considered part of the German Idealism and Romanticism movements, although his philosophy was very singular. He was a thorough-going pessimist who believed that the "will-to-life" (the drive to survive and to reproduce) was the underlying driving force of the world, and that the pursuit of happiness, love and intellectual satisfaction was very much secondary and essentially futile. He saw art (and other artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness) as the only way to overcome the fundamentally frustration-filled and painful human condition. The greatest and most influential of the German Idealists, though, was Georg Hegel. Although his works have a reputation forabstractness and difficulty, Hegel is often considered the summit of early 19th Century German thought, and his influencewas profound. He extended Aristotle's process of dialectic (resolving a thesis and its opposing antithesis into a synthesis) to apply to the real world - including the whole of history - in an on-going process of conflict resolution towards what he called theAbsolute Idea. However, he stressed that what is really changing in this process is the underlying "Geist" (mind, spirit, soul), and he saw each person's individual consciousness as being part of an Absolute Mind (sometimes referred to as Absolute Idealism). Karl Marx was strongly influenced by Hegel's dialectical method and his analysis of history. His Marxist theory (including the concepts of historical materialism, class struggle, the labour theory of value, the bourgeousie, etc), which he developed with his friend Friedrich Engels as a reaction against the rampant Capitalism of 19th Century Europe, provided the intellectual base for later radical and revolutionary Socialism and Communism. A very different kind of philosophy grew up in 19th Century England, out of the British Empiricist tradition of the previous century. The Utilitarianism movement was founded by the radical social reformer Jeremy Bentham and popularized by his even more radical protegé John Stuart Mill. The doctrine of Utilitarianism is a type of Consequentialism (an approach to Ethicsthat stresses an action's outcome or consequence), which holds that the right action is that which would cause "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". Mill refined the theory to stress the quality not just the quantity of happiness, andintellectual and moral pleasures over more physical forms. He counselled that coercion in society is only justifiable either to defend ourselves, or to defend others from harm (the "harm principle"). 19th Century America developed its own philosophical traditions. Ralph Waldo Emerson established the Transcendentalismmovement in the middle of the century, rooted in the transcendental philosophy of Kant, German Idealism and Romanticism, and a desire to ground religion in the inner spiritual or mental essence of humanity, rather than in sensuous experience.Emerson's student Henry David Thoreau further developed these ideas, stressing intuition, selfexamination, Individualism and the exploration of the beauty of nature. Thoreau's advocacy of civil disobedience influenced generations of social reformers. The other main American movement of the late 19th Century was Pragmatism, which was initiated by C. S. Peirce and developed and popularized by William James and John Dewey. The theory of Pragmatism is based on Peirce's pragmatic maxim, that the meaning of any concept is really just the same as its operational or practical consequences (essentially, that something is true only insofar as it works in practice). Peirce also introduced the idea of Fallibilism (that all truths and "facts" are necessarily provisional, that they can never be certain but only probable). James, in addition to his psychological work, extended Pragmatism, both as a method for analyzing philosophic problems but also as a theory of truth, as well as developing his own versions of Fideism (that beliefs are arrived at by an an individual process that lies beyond reason and evidence) and Voluntarism (that the will is superior to the intellect and to emotion) among others. Dewey's interpretation of Pragmatism is better known as Instrumentalism, the methodological view that concepts and theories are merely useful instruments, best meaured by how effective they are in explaining and predicting phenomena, and not by whether they are true or false (which he claimed was impossible). Dewey's contribution to Philosophy of Education and to modern progressive education (particularly what he called "learning-by-doing") was also significant. But European philosophy was not limited to the German Idealists. The French sociologist and philosopher Auguste Comtefounded the influential Positivism movement around the belief that the only authentic knowledge was scientific knowledge, based on actual sense experience and strict application of the scientific method. Comte saw this as the final phase in theevolution of humanity, and even constructed a non-theistic, pseudo-mystical "positive religion" around the idea. The Dane Søren Kierkegaard pursued his own lonely trail of thought. He too was a kind of Fideist and an extremely religiousman (despite his attacks on the Danish state church). But his analysis of the way in which human freedom tends to lead to"angst" (dread), the call of the infinite, and eventually to despair, was highly influential on later Existentialists like Heideggerand Sartre. The German Nietzsche was another atypical, original and controversial philosopher, also considered an important forerunner ofExistentialism. He challenged the foundations of Christianity and traditional morality (famously asserting that "God is dead"), leading to charges of Atheism, Moral Skepticism, Relativism and Nihilism. He developed original notions of the "will to power" as mankind's main motivating principle, of the "Übermensch" ("superman") as the goal of humanity, and of "eternal return" as a means of evaluating ones life, all of which have all generated much debate and argument among scholars. 20th Century Philosophy Back to Top 20th Century philosophy has been dominated to a great extent by the rivalry between two very general philosophical traditions,Analytic Philosophy (the largely, although not exclusively, anglophone mindset that philosophy should apply logical techniques and be consistent with modern science) and Continental Philosophy (really just a catch-all label for everything else, mainly based in mainland Europe, and which, in very general terms, rejects Scientism and tends towards Historicism). An important precursor of the Analytic Philosophy tradition was the Logicism developed during the late 19th Century by Gottlob Frege. Logicism sought to show that some, or even all, of mathematics was reducible to Logic, and Frege's work revolutionized modern mathematical Logic. In the early 20th Century, the British logicians Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whiteheadcontinued to champion his ideas (even after Russell had pointed out a paradox exposing an inconsistency in Frege's work, which caused him, Frege, to abandon his own theory). Russell and Whitehead's monumental and ground-breaking book,"Principia Mathematica" was a particularly important milestone. Their work, in turn, though, fell prey to Kurt Gödel's infamousIncompleteness Theorems of 1931, which mathematically proved the inherent limitations of all but the most trivial formal systems. Both Russell and Whitehead went on to develop other philosophies. Russell's work was mainly in the area of Philosophy of Language, including his theory of Logical Atomism and his contributions to Ordinary Language Philosophy. Whiteheaddeveloped a metaphysical approach known as Process Philosophy, which posited everchanging subjective forms to complement Plato's eternal forms. Their Logicism, though, along with Comte's Positivism, was a great influence on the development of the important 20th Century movement of Logical Positivism. The Logical Positivists campaigned for a systematic reduction of all human knowledge down to logical and scientific foundations, and claimed that a statement can be meaningful only if it is either purely formal (essentially, mathematics and logic) or capable of empirical verification. The school grew from the discussions of the so-called "Vienna Circle" in the early 20th Century (including Mauritz Schlick, Otto Neurath, Hans Hahn and Rudolf Carnap). In the 1930s, A. J. Ayer was largely responsible for the spread of Logical Positivism to Britain, even as its influence was already waning in Europe. The "Tractatus" of the young Ludwig Wittgenstein, published in 1921, was a text of great importance for Logical Positivism. Indeed, Wittgenstein has come to be considered one of the 20th Century's most important philosophers, if not the most important. A central part of the philosophy of the "Tractatus" was the picture theory of meaning, which asserted thatthoughts, as expressed in language, "picture" the facts of the world, and that the structure of language is also determined bythe structure of reality. However, Wittgenstein abandoned his early work, convinced that the publication of the "Tractatus" had solved all the problems of all philosophy. He later re-considered and struck off in a completely new direction. His later work, which saw the meaning of a word as just its use in the language, and looked at language as a kind of game in which the different parts function and have meaning, was instrumental in the development of Ordinary Language Philosophy. Ordinary Language Philosophy shifted the emphasis from the ideal or formal language of Logical Positivism to everyday language and its actual use, and it saw traditional philosophical problems as rooted in misunderstandings caused by thesloppy use of words in a language. Some have seen Ordinary Language Philosophy as a complete break with, or reaction against, Analytic Philosophy, while others have seen it as just an extension or another stage of it. Either way, it became adominant philosophic school between the 1930s and 1970s, under the guidance of philosophers such as W. V. O. Quine,Gilbert Ryle, Donald Davidson, etc. Quine's work stressed the difficulty of providing a sound empirical basis where language, convention, meaning, etc, are concerned, and also broadened the principle of Semantic Holism to the extreme position that a sentence (or even an individualword) has meaning only in the context of a whole language. Ryle is perhaps best known for his dismissal of Descartes' body-mind Dualism as the "ghost in the machine", but he also developed the theory of Philosophical Behaviourism (the view that descriptions of human behaviour need never refer to anything but the physical operations of human bodies) which became the standard view among Ordinary Language philosophers for several decades. Another important philosopher in the Analytic Philosophy of the early 20th century was G. E. Moore, a contemporary of Russellat Cambridge University (then the most important centre of philosophy in the world). His 1903 "Principia Ethica" has become one of the standard texts of modern Ethics and Meta-Ethics, and inspired the movement away from Ethical Naturalism (the belief that there exist moral properties, which we can know empirically, and that can be reduced to entirely non-ethical or natural properties, such as needs, wants or pleasures) and towards Ethical NonNaturalism (the belief that there are no such moral properties). He pointed out that the term "good", for instance, is in fact indefinable because it lacks natural properties in the way that the terms "blue", "smooth", etc, have them. He also defended what he called "common sense" Realism (as opposed to Idealism or Skepticism) on the grounds that common sense claims about our knowledge of the world are just as plausibleas those other metaphysical premises. On the Continental Philosophy side, an important figure in the early 20th Century was the German Edmund Husserl, who founded the influential movement of Phenomenology. He developed the idea, parts of which date back to Descartes and evenPlato, that what we call reality really consists of objects and events ("phenomena") as they are perceived or understood in thehuman consciousness, and not of anything independent of human consciousness (which may or may nor exist). Thus, we can"bracket" (or, effectively, ignore) sensory data, and deal only with the "intentional content" (the mind's built-in mental description of external reality), which allows us to perceive aspects of the real world outside. It was another German, Martin Heidegger (once a student of Husserl), who was mainly responsible for the decline ofPhenomenology. In his groundbreaking "Being and Time" of 1927, Heidegger gave concrete examples of how Husserl's view (of man as a subject confronted by, and reacting to, objects) broke down in certain (quite common) circumstances, and how theexistence of objects only has any real significance and meaning within a whole social context (what Heidegger called "being in the world"). He further argued that existence was inextricably linked with time, and that being is really just an ongoing process of becoming (contrary to the Aristotelian idea of a fixed essence). This line of thinking led him to speculate that we can only avoid what he called "inauthentic" lives (and the anxiety which inevitably goes with such lives) by accepting how things are in the real world, and responding to situations in an individualistic way (for which he is considered by many a founder ofExistentialism). In his later work, Heidegger went so far as to assert that we have essentially come to the end of philosophy, having tried out and discarded all the possible permutations of philosophical thought (a kind of Nihilism). The main figurehead of the Existentialism movement was Jean-Paul Sartre (along with his French contemporaries Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir and Maurice Merleau-Ponty). A confirmed Atheist and a committed Marxist and Communist for most of his life, Sartre adapted and extended the work of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Husserl and Heidegger, and concluded that"existence is prior to essence" (in the sense that we are thrust into an unfeeling, godless universe against out will, and that we must must then establish meaning for our lives by what we do and how we act). He believed that we always have choices(and therefore freedom) and that, while this freedom is empowering, it also brings with it moral responsibility and an existential dread (or "angst"). According to Sartre, genuine human dignity can only be achieved by our active acceptance of this angst and despair. In the second half of the 20th Century, three main schools (in addition to Existentialism) dominated Continental Philosophy.Structuralism is the broad belief that all human activity and its products (even perception and thought itself) are constructedand not natural, and that everything has meaning only through the language system in which we operate. Post-Structuralism is a reaction to Structuralism, which stresses the culture and society of the reader over that of the author). Post-Modernism is an even less well-defined field, marked by a kind of "pick'n'mix" openness to a variety of different meanings and authorities from unexpected places, as well as a willingness to borrow unashamedly from previous movements or traditions. The radical and iconoclastic French philosopher Michel Foucault, has been associated with all of these movements (although he himself always rejected such labels). Much of his work is language-based and, among other things, he has looked at how certain underlying conditions of truth have constituted what was acceptable at different times in history, and how the bo dy and sexuality are cultural constructs rather than natural phenomena. Although sometimes criticized for his lax standards of scholarship, Foucault's ideas are nevertheless frequently cited in a wide variety of different disciplines. Mention should also be made of Deconstructionism (often called just Deconstruction), a theory of literary criticism thatquestions traditional assumptions about certainty, identity and truth, and looks for the underlying assumptions (both unspoken and implicit), as well as the ideas and frameworks, that form the basis for thought and belief. The method wasdeveloped by the Frenchman Jacques Derrida (who is also credited as a major figure in Post-Structuralism). His work is highlycerebral and self-consciously "difficult", and he has been repeatedly accused of pseudophilosophy and sophistry. Back to Top of Page General | By Branch/Doctrine | By Historical Period | By Movement/School | By Individual Philosopher © 2008 Luke Mastin The Pre-Socratic period of the Ancient era of philosophy refers to Greek philosophers active before Socrates, or contemporaries of Socrates who expounded on earlier knowledge. They include the following major philosophers: Thales of Miletos (c. 624 - 546 B.C.) Greek Anaximander (c. 610 - 546 B.C.) Greek Anaximenes (c. 585 - 525 B.C.) Greek Pythagoras (c. 570 - 490 B.C.) Greek Heraclitus (c. 535 - 475 B.C.) Greek Parmenides of Elea (c. 515 - 450 B.C.) Greek Anaxagoras (c. 500 - 428 B.C.) Greek Empedocles (c. 490 - 430 B.C.) Greek Zeno of Elea (c. 490 - 430 B.C.) Greek Protagoras (c. 490 - 420 B.C.) Greek Gorgias (c. 487 - 376 B.C.) Greek Democritus (c. 460 - 370 B.C.) Greek Generally speaking, all that remains of their works are a few textual fragments and the QUOTATIONS of later philosophersand historians. The Pre-Socratic philosophers rejected traditional mythological explanations for the phenomena they saw around them in favor of more rational explanations. They started to ask questions like where did everything come from, and why is there such variety, and how can nature be described mathematically? They tended to look for universal principles to explain the whole of Nature. Although they are arguably more important for the questions they asked than the answers they arrived at, the problems and paradoxes they identified became the basis for later mathematical, scientific and philosophic study. Important movements of the period include the Milesian School, the Eleatic School, the Ephesian Schoo Socrates (c. 469 - 399 B.C.) was a hugely important Greek philosopher from theClassical period (often known as the Socratic period in his honour). Unlike most of the Pre-Socratic philosophers who came before him, who were much more interested in establishing how the world works, Socrates was more concerned with how people should behave, and so was perhaps the first major philosopher of Ethics. An enigmatic figure known to us only through other people's accounts (principally the dialogues of his student Plato), he is credited as one of the founders of Western Philosophy. He is considered by some as the very antithesis of the Sophists of his day, who claimed to have knowledge which they could transmit to others (often for payment), arguing instead that knowledge should be pursued for its own sake, even if one could never fully possess it. He made important and lasting contributions in the fields of Ethics, Epistemology andLogic, and particularly in the methodology of philosophy (his Socratic Method or"elenchus"). His views were instrumental in the development of many of the major philosophical movements and schools which came after him, including Platonism(and the Neo-Platonism and Aristotelianism it gave rise to), Cynicism, Stoicism andHedonism. Life Socrates was born, as far as we know, in Athens around 469 B.C. Our knowledge of his life is sketchy and derives mainly from three contemporary sources, thedialogues of Plato and Xenophon (c. 431 - 355 B.C.), and the plays of Aristophanes (c. 456 - 386 B.C.). According to Plato, Socrates' father was Sophroniscus (a sculptor and stonemason) and his mother was Phaenarete (a midwife). His family wasrespectable in descent, but humble in means. He appears to have had no more than an ordinary Greek education (reading, writing, gymnastics and music, and, later, geometry and astronomy) before devoting his time almost completely to intellectual interests. He is usually described as unattractive in appearance and short in stature, and he apparently rarely washed or changed his clothes. But he did nevertheless marry Xanthippe, a woman much younger than he and renowned for her shrewishness(Socrates justified his marriage on the grounds that a horse-trainer needs to hone his skills on the most spirited animals). She bore for him three sons, Lamprocles, Sophroniscus and Menexenus, who were all were quite young children at the time of their father's trial and death and, according to Aristotle, they turned out unremarkable, silly and dull. It is not known for sure who his teachers were, but he seems to have been acquainted with the doctrines of Parmenides,Heraclitus and Anaxagoras. Plato recorded the fact that Socrates met Zeno of Elea and Parmenides on their trip to Athens, probably in about 450 B.C. Other influences which have been mentioned include a rhetorician named Prodicus, a student ofAnaxagoras called Archelaus, and two women (besides his mother): Diotima (a witch and priestess from Mantinea who taught him all about "eros" or love), and Aspasia (the mistress of the Greek statesman Pericles, who taught him the art of funeral orations). It is not clear how Socrates earned a living. Some sources suggest that he continued the profession of stonemasonry from his father. He apparently served for a time as a member of the senate of Athens, and he served (and reportedly distinguished himself) in the Athenian army during three campaigns at Potidaea, Amphipolis and Delium. However, most texts seem to indicate that Socrates did not work, devoting himself solely to discussing philosophy in the squares of Athens. Using a method now known as the Socratic Method (or Socratic dialogue or dialectic), he grew famous for drawing forth knowledge from his students by pursuing a series of questions and examining the implications of their answers. Often he would questionpeople's unwarranted confidence in the truth of popular opinions, but usually without offering them any clear alternativeteaching. Aristophanes portrayed Socrates as running a Sophist school and accepting payment for teaching, but other sources explicitly deny this. The best known part of Socrates' life is his trial and execution. Despite claiming complete loyalty to his city, Socrates' pursuit of virtue and his strict adherence to truth clashed with the course of Athenian politics and society (particularly in the aftermath of Athens' embarrassing defeats in the Peloponnesian War with Sparta). Socrates raised questions about Athenian religion, but also about Athenian democracy and, in particular, he praised Athens' arch-rival Sparta, causing some scholars to interpret his trial as an expression of political infighting. However, it more likely resulted from his self-appointed position as Athens'social and moral critic, and his insistence on trying to improve the Athenians' sense of justice (rather than upholding the status quo and accepting the development of immorality). His "crime" was probably merely that his paradoxical wisdommade several prominent Athenians look foolish in public. Whatever the motivation, he was found guilty (by a narrow margin of 30 votes out of the 501 jurors) of impiety and corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and he was sentenced to death by drinking a mixture containing poison hemlock in 399B.C., at the age of 70. Although he apparently had an opportunity to escape, he chose not to, believing that a true philosopher should have no fear of death, that it would be against his principles to break his social contract with the state by evading its justice, and that he would probably fare no better elsewhere even if he were to escape into exile. Work Back to Top As has been mentioned, Socrates himself did not write any philosophical texts, and our knowledge of the man and his philosophy is based on writings by his students and contemporaries, particularly Plato's dialogues, but also the writings ofAristotle, Xenophon and Aristophanes. As these are either the partisan philosophical texts of his supporters, or works ofdramatic rather than historically accurate intent, it is difficult to find the “real” Socrates (often referred to as the "Socratic problem"). In Plato's Socratic Dialogues in particular, it is well nigh impossible to tell which of the views attributed to Socrates are actually his and which Plato's own. Perhaps Socrates' most important and enduring single contribution to Western thought is his dialectical method of inquiry, which he referred to as "elenchus" (roughly, "cross-examination") but which has become known as the Socratic Method orSocratic Debate (although some commentators have argued that Protagoras actually invented the “Socratic” method). It has been called a negative method of hypothesis elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying andeliminating those which lead to contradictions. Even today, the Socratic Method is still used in classrooms and law schools as a way of discussing complex topics in order to expose the underlying issues in both the subject and the speaker. Its influence is perhaps most strongly felt today in the use of the Scientific Method, in which the hypothesis is just the first stage towards a proof. At its simplest, the Socratic Method is used to solve a problem by breaking the problem down into a series of questions, the answers to which gradually distill better and better solutions. Both the questioner and the questioned explore the implicationsof the other's positions, in order to stimulate rational thinking and illuminate ideas. Thus, Socrates would counter any assertion with a counterexample which disproves the assertion (or at least shows it to be inadequate). This would lead to amodified assertion, which Socrates would then test again with another counterexample. Through several iterations of this kind, the original assertion is continually adjusted and becomes more and more difficult to refute, which Socrates held meant that it was closer and closer to the truth. Socrates believed fervently in the immortality of the soul, and he was convinced that the gods had singled him out as a kind ofdivine emissary to persuade the people of Athens that their moral values were wrong-headed, and that, instead of being so concerned with their families, careers, and political responsibilities, they ought to be worried about the "welfare of their souls". However, he also questioned whether "arete" (or "virtue") can actually be taught as the Sophists believed. He observed that many successful fathers (such as the prominent military general Pericles, for example) did not produce sons of their own quality, which suggested to him that moral excellence was more a matter of divine bequest than parental nurture. He often claimed that his wisdom was limited to an awareness of his own ignorance, (although he did claim to have knowledge of "the art of love"). Thus, he never actually claimed to be wise, only to understand the path a lover of wisdom must take in pursuing it. His claim that he knew one and only one thing, that he knew nothing, may have influenced the later school of Skepticism. He saw his role, not as a teacher or a theorist, but as analogous to a midwife who could bring thetheories of others to life, although to do so he would of course need to have experience and knowledge of that of which he talked. He believed that anyone could be a philosopher, not just those who were highly trained and educated, and indeed that everyone had a duty to ask philosophical questions (he is famously quoted as claiming that "the unexamined life is not worth living"). Many of the beliefs traditionally attributed to the historical Socrates have been characterized as "paradoxical" because they seem to conflict with common sense, such as: no-one desires evil, no-one errs or does wrong willingly or knowingly; all virtue is knowledge; virtue is sufficient for happiness. He believed that wrongdoing was a consequence of ignorance and those who did wrong knew no better (sometimes referred to as Ethical Intellectualism). He believed the best way for people to live was to focus on self-development rather than the pursuit of material wealth, and he always invited others to try to concentrate more onfriendships and a sense of true community. He was convinced that humans possessed certain virtues (particularly the important philosophical or intellectual virtues), and that virtue was the most valuable of all possessions, and the ideal life should be spent in search of the Good (an early statement of Eudaimonism or Virtue Ethics). Socrates' political views, as represented in Plato's dialogue "The Republic", were strongly against the democracy that had so recently been restored in the Athens of his day, and indeed against any form of government that did not conform to his ideal of a perfect republic led by philosophers, who he claimed were the only type of person suitable to govern others. He believed that the will of the majority was not necessarily a good method of decision-making, but that it was much more important that decisions be logical and defensible. However, these may be more Plato's own views than those of Socrates, "The Republic"being a "middle period" work often considered to be not representative of the views of the historical Socrates. In Plato's "early" dialogue, "Apology of Socrates", Socrates refused to pursue conventional politics, on the grounds that he could not look into the matters of others (or tell people how to live their lives) when he did not yet understand how to live his own. Some have argued that he considered the rule of the "Thirty Tyrants" (who came to power briefly during his life, led byCritias, a relative of Plato and a one-time student of Socrates himself) even less legitimate than the democratic senate that sentenced him to death. Likewise, in the dialogues of Plato, Socrates often appears to support a mystical side, discussing reincarnation and themystery religions (popular religious cults of the time, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries, restricted to those who had gone through certain secret initiation rites), but how much of this is attributable to Socrates or to Plato himself is not (and never will be) clear. Socrates often referred to what the Greeks called a "daemonic sign", a kind of inner voice he heard only when he was about to make a mistake (such as the sign that he claimed prevented him from entering into politics). Although we would consider this to be intuition today, Socrates thought of it as a form of "divine madness", the sort of insanity that is a gift from the gods and gives us poetry, mysticism, love and even philosophy itself. Socrates' views were instrumental in the development of many of the major philosophical movements and schools which came after him, particularly the Platonism of his principle student Plato, (and the Neo-Platonism and Aristotelianism it gave rise to). His idea of a life of austerity combined with piety and morality (largely ignored by Plato and Aristotle) was essential to the core beliefs of later schools like Cynicism and Stoicism. Socrates' stature in Western Philosophy returned in full force with theRenaissance and the Age of Reason in Europe when political theory began to resurface under such philosophers as John Lockeand Thomas Hobbes. Aristippus of Cyrene (c. 435 - 360 B.C.), the founder of the school of Hedonism was also a pupil of Socrates, although he rather skewed Socrates' teaching. Back to Top of Page General | By Branch/Doctrine | By Historical Period | By Movement/School | By Individual Philosopher © 2008 Luke Aristotelianism is a school or tradition of philosophy from the Socratic (or Classical) period of ancient Greece, that takes itsdefining inspiration from the work of the 4th Century B.C. philosopher Aristotle. His immediate followers were also known as the Peripatetic School (meaning itinerant or walking about, after the covered walkways at the Lyceum in Athens where they often met), and among the more prominent members (other than Aristotlehimself) were Theophrastus (322 - 288 B.C.), Eudemus of Rhodes (c. 370 - 300 B.C.), Dicaearchus (c. 350 285 B.C.), Strato of Lampsacus (288 - 269 B.C.), Lyco of Troas (c. 269 - 225 B.C.), Aristo of Ceos (c. 225 190 B.C.), Critolaus (c. 190 - 155 B.C.),Diodorus of Tyre (c. 140 B.C.), Erymneus (c. 110 B.C.) and Alexander of Aphrodisias (c. 200 A.D.). Aristotle developed the earlier philosophical work of Socrates and Plato in a more practical and down-to-earth manner, and was the first to create a comprehensive system of philosophy, encompassing Ethics, Metaphysics, Aesthetics, Logic,Epistemology, Politics and Science. He rejected the Rationalism and Idealism espoused by Platonism, and advocated the characteristic Aristotelian virtue of "phronesis" (practical wisdom or prudence). Another cornerstone of Aristotelianism is the idea of teleology (the idea that all things are designed for, or directed toward, a final result or purpose). Aristotelian Logic was the dominant form of Logic until 19th Century advances in mathematical logic, and as late as the 18th Century Kant stated that Aristotle's theory of logic completely accounted for the core of deductive inference. His six books onLogic, organized into a collection known as the "Organon" in the 1st Century B.C., remain standard texts even today. Aristotle's works on Ethics (particularly the "Nicomachean Ethics" and the "Eudemian Ethics") revolve around the idea that morality is a practical, not a theoretical, field, and, if a person is to become virtuous, he must perform virtuous activities, not simply study what virtue is. The doctrines of Virtue Ethics and Eudaimonism reached their apotheosis in Aristotle's ethical writings. He stressed that man is a rational animal, and that Virtue comes with the proper exercise of reason. He also promoted the idea of the "golden mean", the desirable middle ground, between two undesirable extremes (e.g. the virtue of courage is a mean between the two vices of cowardice and foolhardiness). Aristotelian Metaphysics and Epistemology largely follow those of his teacher, Plato, although he began to diverge on some matters. Aristotle assumed that for knowledge to be true it must be unchangeable, as must the object of that knowledge. The universe therefore divides into two phenomena, Form (the abstract and unobservable, such as souls or knowledge) and Matter(the observable, things that can be sensed and quantified), and these two phenomena are different from, but indispensable to, each other. Aristotle's conception of hylomorphism (the idea that substances are forms inhering in matter) differed from that of Plato in that he held that Form and Matter are inseparable, and that matter and form do not exist apart from each other, butonly together. Aristotle's theory of Politics emphasizes the belief that humans are naturally political, and that the political life of a free citizenin a self-governing state or "polis" (with a constitution which is a mixture of leadership, aristocracy and citizen participation) is the highest form of life. Aristotelian ideals have underlain much modern liberal thinking about politics, the vote and citizenship. Although much of Aristotle's work was lost to Western Philosophy after the fall of the Roman Empire, the texts werereintroduced into the West by medieval Islamic scholars like Averroes and Maimonides. Just as these Muslim philosophers reconciled Aristotelianism with Islamic beliefs, St. Thomas Aquinas was largely responsible for reconciling Aristotelianism withChristianity, arguing that it complements and completes the truth revealed in the Christian tradition. It became the dominant philosophic influence on Scholasticism and Thomism in the early Middle Ages in Europe. The distinctively Aristotelian idea of teleology was transmitted through the German philosophers Christian Wolff (1679 1754) and Immaneul Kant to Georg Hegel, who applied it to history as a totality, resulting in turn in an important Aristotelian influenceupon Karl Marx. The lasting legacy of Aristotelianism can be seen in the works of contemporary philosophers such as John McDowell (1942 - ), Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900 - 2002) and Alasdair MacIntyre (1929 - ). Back to Top of Page General | By Branch/Doctrine | By Historical Period | By Movement/School | By Individual Philosopher © 2008 Luke Mastin Platonism is an ancient Greek school of philosophy from the Socratic period, founded around 387 B.C. by Socrates' student and disciple, Plato, and continued by his students and followers. It was based in the Academy, a precinct containing a sacred grove outside the walls of Athens, where Plato delivered his lectures (the protoype for later universities). Platonism was originally expressed in the dialogues of Plato, in which the figure of his teacher, Socrates, is used to expound various doctrines. Plato's philosophy is best known for its Platonic Realism (also, confusingly, known as Platonic Idealism), its hylomorphism(the idea that substances are forms inhering in matter) and its Theory of Forms ("Forms" are the eternal, unchangeable, perfect universals, of which the particular objects we sense around us are imperfect copies). It poses an eternal universe, and describes idea as prior to matter, so that the substantive reality around us is only a reflection of a higher truth. (see the section on Platonic Realism for more details). Platonic Epistemology holds that knowledge is innate, and the immortal soul "remembers" its prior familiary with the Forms ("anamnesis"). Learning is therefore the development of ideas buried deep in the soul. Of these, the Form of "the Good" (the ideal or perfect nature of goodness) is the ultimate basis for the rest, and the first cause of being and knowledge. Plato held that the impressions of the senses can never give us the knowledge of true being (i.e. of the Forms), which can only be obtained by the exercise of reason through the process of dialectic (the exchange of arguments and counter-arguments, propositions and count er-propositions). Platonic Ethics is based on the concept that virtue is a sort of knowledge (the knowledge of good and evil) that is required to reach the ultimate good ("eudaimonia" or happiness), which is what all human desires and actions aim to achieve (see the section on Eudaimonism). It holds that there are three parts to the soul, Reason, Spirit and Appetite, which must be ruled by the three virtues, Wisdom, Courage and Moderation. These are, in turn, all ruled by a fourth, Justice, by which each part of the soul is confined to the performance of its proper function. The Academy, in which the school was based, is usually split into three periods: the Old, Middle, and New Academy. The chief figures in the Old Academy were: Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, who rapidly developed his own set of philosophies and a whole separate Aristotelian tradition; Speusippus (407 - 339 B.C.), Plato's nephew, who succeeded as head of the school afterPlato's death in 347 B.C.; Xenocrates (396 - 314 B.C.) who was head from 339 B.C. to 314 B.C.; Polemo, from 314 B.C. to 269 B.C.; and Crates, from 269 B.C. to 266 B.C. After this time, the Middle Academy and New Academy were more vehicles forSkepticism than Platonism proper, before being re-founded, after a lapse during the early Roman occupation, as a Neo-Platonist institution in 410 A.D. Around 90 B.C., a period known as Middle Platonism began, when Antiochus of Ascalon (c. 130 - 68 B.C.) rejected Skepticism, and propounded a fusion of Platonism with some Aristotelian and Stoic dogmas. Philo of Alexandria can also be considered a Middle Platonist, as he attempted to synthesize Platonism with monotheistic religion, anticipating the Neo-Platonism of later philosophers such as Plotinus. Platonism influenced Christianity first through Clement of Alexandria (c.150 - 216 A.D.) and Origen (c. 185 - 254 A.D.), and especially later through St. Augustine of Hippo, who was one of the most important figures in the development of Western Christianity. Platonism was considered authoritative in the Middle Ages, and many Platonic notions are now permanent elements of Latin Christianity, as well as both Eastern and Western mysticism. Back to Top of Page General | By Branch/Doctrine | By Historical Period | By Movement/School | By Individual Philosopher © 2008 Luke Mastin