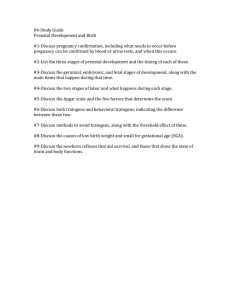

Research www. AJOG.org OBSTETRICS Type of delivery is not affected by light resistance and toning exercise training during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial Ruben Barakat, PhD; Jonatan R. Ruiz, PhD; James R. Stirling, PhD; María Zakynthinaki, PhD; Alejandro Lucia, MD, PhD OBJECTIVE: We examined the effect of light-intensity resistance ex- RESULTS: The percentage of women who had normal, instrumental, or ercise training that is performed during the second and third trimester of pregnancy by previously sedentary and healthy women on the type of delivery and on the dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time. cesarean delivery was similar in the training (70.8%, 13.9%, and 15.3%, respectively) and control (71.4%, 12.9%, and 15.7%, respectively) groups. The mean dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time did not differ between groups. STUDY DESIGN: We randomly assigned 160 sedentary women to either a training (n ⫽ 80) or a control (n ⫽ 80) group. We recorded several maternal and newborn characteristics, the type of delivery (normal, instrumental, or cesarean), and dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time. CONCLUSION: Light-intensity resistance training that is performed over the second and third trimester of pregnancy does not affect the type of delivery. Key words: cesarean delivery, resistance training, vaginal delivery Cite this article as: Barakat R, Ruiz JR, Stirling JR, et al. Type of delivery is not affected by light resistance and toning exercise training during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:590.e1-6. P regnant women have been encouraged traditionally to reduce physical activity because of perceived increased risk of problems, such as early pregnancy loss or reduced placental circulation.1 The number of women who engage in regular exercise (or who are willing to From Facultad de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte–INEF, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain (Drs Barakat and Stirling) and Instituto de Ciencias Matemáticas, CSIC-UAM-UC3M–UCM, Madrid, Spain, (Dr Zakynthinaki), and Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain (Dr Lucia), and the Department of Biosciences and Nutrition at NOVUM, Unit for Preventive Nutrition, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden (Dr Ruiz). Received Nov. 6, 2008; revised Dec. 5, 2008; accepted June 1, 2009. Reprints not available from the authors. This work was supported in part by the program I3 2006 and by the postdoctoral research program EX-2007-1124, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain. The first 2 authors contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript. 0002-9378/$36.00 © 2009 Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.004 590.e1 do so) during pregnancy, however, has increased in the last years.2 This tendency is overall supported by the bulk of scientific evidence. Several publications over the last decade have reported few negative effects of physical activity on the pregnancy of a healthy pregnant woman.3-6 Further, physical activity during pregnancy could be beneficial to the maternal-fetal unit and prevent the occurrence of maternal disorders, such as hypertension.7 Recent guidelines by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists promotes regular exercise for pregnant women, including sedentary ones, for its overall health benefits, which includes possibly a decreased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus.8,9 Obstetricians lack sufficient information to provide constructive guidance for their patients who want to be physically active over the entire pregnancy, because several questions remain to be answered. One important question that frequently is addressed relates to the possibility that high physical activity levels, especially during the second part of pregnancy, might affect main gestational outcomes, which would include gestational age and type of delivery. Data from noncontrolled10 and controlled training studies American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2009 on small11 or large12 population samples and from prospective reports on large population samples showed no association between physical activity during pregnancy and gestational age, risk of preterm delivery, or intrauterine growth.3,13-18 Less data are available on the association between physical activity during pregnancy and the type of delivery. A prospective study showed that, in previously well-conditioned women, continuation of their exercise regimens (aerobics or running) during the second half of pregnancy had a beneficial effect on the course and outcome of labor (ie, lower incidence of abdominal and normal [vaginal] operative delivery).19 This is in agreement with prospective data on previously sedentary nulliparous women that shows that regular participation in aerobic exercise during the first 2 trimesters of pregnancy can be associated with reduced risk for cesarean delivery.20 In a study by Hall and Kaufmann,21 845 women were given the option to participating or not in a prenatal exercise program of different intensities that involved weight-lifting and stationary bicycling. The proportion of vaginal deliveries increased with the intensity of the program. Obstetrics www.AJOG.org FIGURE Flow diagram of the study participants Assessed for eligibility (n = 480) Excluded from the study (n = 320) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 199) Refused to participate (n = 121) Other reasons (n = 0) Enrollment Randomized (n = 160) Allocation Follow-up Analysis Allocated to intervention (n = 80, training) Received intervention (n = 80) Did not receive intervention (n = 0) Allocated to intervention (n = 80, controls) Received intervention (n = 80) Did not receive intervention (n = 0) Lost to follow-up (n = 0) Discontinued intervention (n = 8) Risk for premature labour (n = 1) Pregnancy-induced hypertension (n = 1) Persistent bleeding (n = 1) Personal reasons (n = 5) Lost to follow-up (n = 5) Discontinued intervention (n = 5) Gave birth in a different hospital (n = 5) Pregnancy-induced hypertension (n = 2) Threat of premature delivery (n = 2) Molar pregnancy (n = 1) Analyzed (n = 72) Excluded from analysis (n = 0) Analyzed (n = 70) Excluded from analysis (n = 0) Barakat. Delivery not affected by exercise training. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009. Randomized, controlled training trials in large population samples, however, are lacking to objectively and specifically assess the possible cause– effect relationship between exercise interventions during the second half of pregnancy and the type of delivery. Accordingly, it was the purpose of our study to investigate the effects of a supervised maternal exercise training program (performed during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy) on the type of delivery (normal, instrumental, or cesarean) and on dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time. A matched control group was assessed over the same time period. Given that most studies in the field have used aerobic exercise, we largely focused on resistance and toning exercises. Resistance exercise training increases muscular strength and is prescribed currently by sound medical organizations for improving health and fitness.22-25 M ETHODS The present study was a randomized, controlled training trial. A complete description of design and methods has been published elsewhere.12 We contacted a total of 480 Spanish (white) pregnant women of low-to-medium so- cioeconomic class, from a primary care medical center (Centro de Salud María Montesori, Leganés, Madrid, Spain; Figure). A total of 160 healthy pregnant women who were 25-35 years old, who were sedentary (not exercising ⬎20 minutes on ⬎3 days per week), who had singleton and uncomplicated gestation, and who were not at high risk for preterm delivery (no more than 1 previous preterm delivery) were assigned randomly to either a training or control group (n ⫽ 80 each). The participant randomization assignment followed an allocation concealment process.26,27 The researcher in charge of randomly assigning participants did not know in advance which treatment the next person would receive and did not participate in assessment. Assessment staff members were blinded to participant randomization assignment, and participants were reminded to not to discuss their randomization assignments with assessment staff members. All the participants were informed about the aim and study protocol, and all the women provided written informed consent. Women who were not planning to give birth in the same obstetrics hospital department (Hospital Severo Research Ochoa, Madrid, Spain) and not be under medical follow-up throughout the entire pregnancy period were not included in the study. Women who had any serious medical condition that prevented them from exercising safely were not included in the study.8 The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Hospital Severo Ochoa (Madrid, Spain). The study was performed between January 2000 and March 2002 and followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, which was last modified in 2000. Control and intervention groups Women in the nonexercise control group were asked to maintain their level of activity during the study period. All participants were followed throughout the entire pregnancy period. Details of the exercise training protocol have been described by Barakat et al.12 Women in the training group were enrolled in 3 sessions per week for approximately 26 weeks. Heart rate was carefully and individually controlled (Accurex Plus; Polar Electro OY, Finland) through every session and was kept at ⱕ80% of age-predicted maximum heart rate value (220 minus the woman’s age). The exercise training program started in the beginning of the second trimester (week 12-13) and was prolonged until the end of the third trimester (week 3839). We originally planned an average of approximately 80 training sessions for each participant in the event of no preterm delivery. Each exercise training session consisted of a warm-up period of approximately 8 minutes (ⱕ60% maximum heart rate value), approximately 20 minutes of toning and very light resistance exercises (ⱕ80% maximum heart rate value), and a cool-down period of approximately 8 minutes (ⱕ60% maximum heart rate value). The core portion consisted of toning and joint mobilization exercises that involved major muscle and joint groups (ie, shoulder shrugs and rotations, arm elevations, leg lateral elevations, pelvic tilts, and rocks). Resistance exercises were performed with barbells (ⱕ3 kg per exercise) or low-to-medium resistance DECEMBER 2009 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 590.e2 Research Obstetrics bands (Thera-band; The Hygienic Corporation, Akron, OH) and included 1 set of ⱕ10-12 repetitions of abdominal curls, biceps curls, arm extensions, arm side lifts, shoulder elevations, seated bench press, seated lateral row, lateral leg elevations, leg circles, knee extensions, knee (hamstring) curls, and ankle flexion and extensions. Supine postures and exercises that involved extreme stretching and joint overextension, ballistic movements, jumps, and those types of exercises that are performed on the back were specifically avoided. To minimize cardiovascular stress, we specifically instructed participants to avoid the Valsalva maneuver. To reduce participants drop out and to maintain adherence to the training program, all sessions were accompanied with music and were performed in an airy, well-lighted exercise room. A qualified fitness specialist carefully supervised every training session and worked with groups of 10-12 women. We used the exercise training facilities from the primary care medical center where they were monitored through the pregnancy. No women changed from the control group to the intervention group or vice versa. Type of delivery and other outcome measures We obtained type of delivery (normal, instrumental, and cesarean); dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time; use (or not) of epidural anesthesia, and Apgar scores (at 1 and 5 minutes) from the reports of delivery room personnel (midwife). We recorded birthweight, birth length, and head circumference of the newborn infant and gestational age at time of delivery (in weeks, days) from hospital perinatal records. The results of Apgar scores and gestational age have been recently reported.12 We used the Minnesota Leisure-Time physical activity questionnaire to assess the occupational activities and other daily activities, such as number of hours standing.28 We measured weight and height of the mother by standard procedures at the start of the study and before parity and eventual preterm deliveries, which is ⬍37 completed weeks of gesta590.e3 www.AJOG.org tion. Body mass index was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. Smoking habits and alcohol intake at the start of the study and previous parity were recorded through an interview. Statistical analyses We used a conservative approach to sample size estimation. We made power calculations for the primary outcome measures of gestational age, Apgar score, birthweight, and length. We determined that adequate power (⬎0.80) would be achieved with 70 pregnant women in the training group and with 70 pregnant women in the control group. All power computations assumed that comparisons of baseline to 26-week scores would be tested at the 5% significance level. All power computations allowed for 10% dropouts over 26 weeks. We presented maternal and newborn infant characteristics of the study sample by group (training and control) as means and standard deviations (SD), unless otherwise stated. For group comparisons, we analyzed continuous and nominal data with t test for unpaired data and 2 tests, respectively. We compared Apgar scores between groups using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Multiple comparisons were adjusted for mass significance as described by Holm.29 All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 14.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL); the level of significance was set to ⬍ .05. R ESULTS The final number of participants that we included as valid study pregnant women was 72 in the training group and 70 in the control group (Figure). There were no exercise-related injuries experienced during pregnancy, nor were there any cases of gestational diabetes mellitus. The return for follow-up evaluation was ⬎90% for both training and control groups. We noted no major adverse effects and no major health problems in the participants, except for 2 preterm deliveries in the training group and 3 preterm deliveries in the control group. Women in the training group were American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2009 rather pleased with the exercise training, and all of the women reported their intention to be physically active in future pregnancies. There were no protocol deviations from study as planned. Table 1 shows the maternal and newborn infant characteristics in the training and control groups. We did not observe a significant difference between groups in any of the variables that were studied (all P ⬎ .1). The type of delivery and labor times in the training and control group are shown in Table 2. The percentage of women who had natural, instrumental, and cesarean delivery was similar (P ⬎ .1) in the training (70.8%, 13.9%, and 15.3%, respectively) and control group (71.4%, 12.9%, and 15.7%, respectively). Likewise, the mean dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time did not differ between groups (all P ⬎ .1). C OMMENT The main finding of the present randomized controlled trial was that supervised resistance and toning exercise training that is performed over the second and third trimester of pregnancy does not affect the type of delivery nor the mean dilation, expulsion, and childbirth time in previously sedentary healthy pregnant women. Furthermore, we did not observe any effect on the newborn infant’s overall health status. To strengthen our findings, several potential confounding variables that can affect labor outcome (such as prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain age, previous parity history, smoking habits, alcohol intake, number of hours standing, and epidural anesthesia) were appropriately taken into account. Indeed, we did not observe differences between the training and the control group in the aforementioned variables. The mode of exercise training that was followed by the intervention group and the relatively large number of previously sedentary healthy pregnant women who were enrolled in the study are additional strengths of our study. Exercise training consisted mainly of light resistance and toning exercises. Except in the nonrandomized training study by Hall and Kaufmann,21 most previous studies ana- Obstetrics www.AJOG.org Research TABLE 1 Characteristics in the training and control groups Characteristic Training group (n ⴝ 72) Control group (n ⴝ 70) Maternal age (y)a 30.4 ⫾ 2.9 29.5 ⫾ 3.7 Body mass index (kg/m ) 24.3 ⫾ 0.5 23.4 ⫾ 0.5 ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 a,b ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Previous gestation (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 0 52 (72.2%) 40 (57.1%) 1 16 (22.2%) 25 (35.7%) 2 4 (5.6%) 5 (7.1%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Smoking habits (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Yes 16 (22.2%) 20 (28.6%) No 56 (77.8%) 50 (71.4%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Alcohol intake (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Yes 3 (4%) 5 (7%) No 69 (96%) 65 (93%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Occupational activity (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Sedentary job 26 (36.1%) 21 (30.0%) Housewife 31 (43.1%) 30 (42.9%) Active job 15 (20.8%) 19 (27.1%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Hours standing (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ⬎3 h 34 (47.2%) 46 (65.7%) ⬍3 h 38 (52.8%) 24 (34.3%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Maternal education (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ⬍High school 25 (34.7%) 31 (44.3%) High school 28 (38.9%) 30 (42.9%) ⬎High school 19 (26.4%) 9 (12.9%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Previous miscarriage (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 0 59 (81.9%) 58 (82.9%) 1 10 (13.9%) 11 (15.7%) 2 3 (4.2%) 1 (1.4%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Previous low birthweight newborn infant: ⬍2500 g (n) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 0 72 (100%) 68 (97.1%) ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 0 2 (2.9%) 2 (2.8%) 3 (4.3%) ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ c Preterm deliveries (⬍37 weeks) by the end of the study (n) ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ ab Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) 11.5 ⫾ 3.7 12.4 ⫾ 3.4 ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ a Birthweight (g) 3165 ⫾ 411 3307 ⫾ 477 ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ a Birth length (cm) 49.5 ⫾ 1.8 49.7 ⫾ 1.8 ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Apgar score ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... a 1 min 8.9 ⫾ 1.1 8.8 ⫾ 1.2 5 min 9.9 ⫾ 0.2 9.9 ⫾ 0.3 39/4 ⫾ 1/2 39/5 ⫾ 1/2 ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... a ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ a Gestational age (wk/d) ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ a Data are expressed as mean ⫾ SD. We analyzed continuous and nominal data with t test for unpaired data and chi-square tests, respectively; all group comparisons were nonsignificant, with a probability value of ⬎ .1; b there are 6 missing sets of data in the control group that refer to prepregnancy weight and height; c there were no women with ⬎1 previous preterm delivery. Barakat. Delivery not affected by exercise training. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009. DECEMBER 2009 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 590.e4 Research Obstetrics www.AJOG.org TABLE 2 Type of delivery and labor times in the training and control groups Variable Training group (n ⴝ 72) Control group (n ⴝ 70) P value ⬎ .1 Type of delivery ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Natural (n) 51 (70.8%) 50 (71.4%) Instrumental (n) 10 (13.9%) 9 (12.9%) Cesarean (n) 11 (15.3%) 11 (15.7%) 50 (69.4%) 48 (68.6%) ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Epidural anesthesia (n) ⬎ .1 .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. a Dilation time (min) 426 ⫾ 20 378 ⫾ 13 ⬎ .1 .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. a Expulsion time (min) 32.5 ⫾ 24.7 36.0 ⫾ 31.5 ⬎ .1 Childbirth time (min) 8.1 ⫾ 2.3 7.7 ⫾ 1.7 ⬎ .1 esthesia, or longer hospitalization periods) and its higher medical cost.20 In summary, regular supervised exercise training (which consists of light resistance and toning exercises) that are performed over the second and third trimester of pregnancy does not affect delivery type in previously sedentary women. This study adds further evidence to support the overall health benefits of supervised, light-moderate regular exercise for healthy pregnant women with very few (if any) complications. f .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. a .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. a Data are expressed as mean ⫾ SD. Barakat. Delivery not affected by exercise training. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009. lyzed the effect of aerobic exercise on pregnancy outcomes.10,13-20,30 Even of low intensity (as here) resistance exercise should be an integral component of any exercise training program. Indeed, increased muscle strength that is induced by resistance training (eg, as in the trained group here) results in an attenuated cardiovascular stress response to any given load during physical activities of daily living because the load now represents a lower percentage of the maximal voluntary contraction.31 There is increasing evidence of the beneficial effects that improved muscular strength has on the prevention of chronic diseases and on the ability to cope with daily living activities in both healthy and diseased people.32,33 Regular resistancetype physical activities, such as the ones performed by our training group, are main determinants of muscular strength and are recommended for improving public health by major medical organizations.22,23,25,33 Other potential benefits of resistance training during pregnancy include decreased risk of insulin dependence in overweight women with gestational diabetes mellitus34 and also better posture, prevention of gestational low back pain and diastasis recti, and strengthening of the pelvic floor.35,36 Our results show no differences in type of delivery between both groups are in apparent disagreement with previous data from prospective19,20,35 or training21 studies that have suggested that regular exercise that is performed over 590.e5 the course of pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of vaginal delivery. Comparisons between studies, however, are difficult to make because of differences in several variables that can affect delivery type, such as age, body mass index, gestational weight gain age, previous parity history, smoking habits, alcohol intake, number of hours standing, and epidural anesthesia. In any case, the cross-sectional19,20,37 or nonrandomized21 nature of previous studies precludes a true cause– effect relationship from being established between exercise and type of delivery. Further, the etiologic mechanisms behind this reported association remain to be elucidated. Regular sustained exercise during pregnancy traditionally has been a cause of concern because it could potentially challenge the homeostasis of the maternal-fetal unit; thus, it might affect adversely the course and outcome of pregnancy (ie, by inducing changes in visceral blood flow, body temperature, carbohydrate use, or shear-stress).2,19,30,38 Therefore, our findings are of clinical relevance because, in pregnant women, the documented benefits that regular training has on the maternal health status38,39 are not accompanied by a lower incidence of natural deliveries. This type of delivery is generally preferred to cesarean section delivery because of the maternal risks of the latter (eg, infection, excessive blood loss, respiratory complications, reactions to an- American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2009 ACKNOWLEDGMENT We thank the Gynecology and Obstetric Service of Severo Ochoa Hospital of Madrid for technical assistance. REFERENCES 1. Schramm WF, Stockbauer JW, Hoffman HJ. Exercise, employment, other daily activities, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:211-8. 2. Clapp JF 3rd. Exercise during pregnancy: a clinical update. Clin Sports Med 2000;19: 273-86. 3. Sternfeld B, Quesenberry CP Jr, Eskenazi B, Newman LA. Exercise during pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995;27:634-40. 4. Horns PN, Ratcliffe LP, Leggett JC, Swanson MS. Pregnancy outcomes among active and sedentary primiparous women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1996;25:49-54. 5. McMurray RG, Mottola MF, Wolfe LA, Artal R, Millar L, Pivarnik JM. Recent advances in understanding maternal and fetal responses to exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25: 1305-21. 6. Wolfe LA, Brenner IK, Mottola MF. Maternal exercise, fetal well-being and pregnancy outcome. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1994;22:145-94. 7. Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:989-1006. 8. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion, no. 267: exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:171-3. 9. Artal R, O’Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:6-12. 10. Giroux I, Inglis SD, Lander S, Gerrie S, Mottola MF. Dietary intake, weight gain, and birth outcomes of physically active pregnant women: a pilot study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2006;31:483-9. 11. Mark AE, Janssen I. Dose-response relation between physical activity and blood pressure in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:1007-12. Obstetrics www.AJOG.org 12. Barakat R, Stirling JR, Lucia A. Does exercise training during pregnancy affect gestational age? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:674-8. 13. Clapp JF 3rd, Dickstein S. Endurance exercise and pregnancy outcome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1984;16:556-62. 14. Hatoum N, Clapp JF 3rd, Newman MR, Dajani N, Amini SB. Effects of maternal exercise on fetal activity in late gestation. J Matern Fetal Med 1997;6:134-9. 15. Hatch M, Levin B, Shu XO, Susser M. Maternal leisure-time exercise and timely delivery. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1528-33. 16. Klebanoff MA, Shiono PH, Carey JC. The effect of physical activity during pregnancy on preterm delivery and birthweight. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1450-6. 17. Berkowitz GS, Kelsey JL, Holford TR, Berkowitz RL. Physical activity and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. J Reprod Med 1983;28:581-8. 18. Marquez-Sterling S, Perry AC, Kaplan TA, Halberstein RA, Signorile JF. Physical and psychological changes with vigorous exercise in sedentary primigravidae. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:58-62. 19. Clapp JF 3rd. The course of labor after endurance exercise during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1799-805. 20. Bungum TJ, Peaslee DL, Jackson AW, Perez MA. Exercise during pregnancy and type of delivery in nulliparae. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2000;29:258-64. 21. Hall DC, Kaufmann DA. Effects of aerobic and strength conditioning on pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;157: 1199-203. 22. Pollock ML, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: an advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation 2000;101:828-33. 23. Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:364-80. 24. Williams MA, Haskell WL, Ades PA, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2007;116:572-84. 25. Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1081-93. 26. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Grimes DA, Altman DG. Assessing the quality of randomization from reports of controlled trials published in obstetrics and gynecology journals. JAMA 1994;272:125-8. 27. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet 2002;359:614-8. 28. Taylor HL, Jacobs DR Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 1978;31:741-55. 29. Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Statist 1979; 6:65-70. 30. Clapp JF 3rd, Kim H, Burciu B, Lopez B. Beginning regular exercise in early pregnancy: effect on fetoplacental growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1484-8. Research 31. McCartney N, McKelvie RS, Martin J, Sale DG, MacDougall JD. Weight-training-induced attenuation of the circulatory response of older males to weight lifting. J Appl Physiol 1993;74:1056-60. 32. Stump CS, Henriksen EJ, Wei Y, Sowers JR. The metabolic syndrome: role of skeletal muscle metabolism. Ann Med 2006;38: 389-402. 33. Wolfe RR. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:475-82. 34. Brankston GN, Mitchell BF, Ryan EA, Okun NB. Resistance exercise decreases the need for insulin in overweight women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:188-93. 35. de Oliveira C, Lopes MA, Carla Longo e Pereira L, Zugaib M. Effects of pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy. Clinics 2007; 62:439-46. 36. Eliasson K, Nordlander I, Larson B, Hammarstrom M, Mattsson E. Influence of physical activity on urinary leakage in primiparous women. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2005;15: 87-94. 37. Zeanah M, Schlosser SP. Adherence to ACOG guidelines on exercise during pregnancy: effect on pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1993;22:329-35. 38. Clapp JF 3rd. Long-term outcome after exercising throughout pregnancy: fitness and cardiovascular risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199:489.e1-6. 39. Hegaard HK, Pedersen BK, Nielsen BB, Damm P. Leisure time physical activity during pregnancy and impact on gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery and birth weight: a review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:1290-6. DECEMBER 2009 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 590.e6