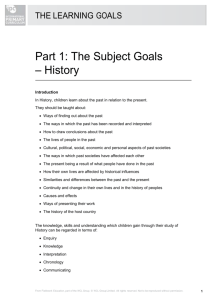

IMYC Implementation File Exit Point Assessment for Learning Entry Point The Big Idea Reflective Journaling Knowledge Harvest Learning Activities From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Contents Welcome to the International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC) 2 What is the IMYC? 4 Teaching with the IMYC ■■ Introduction ■■ Where does good learning come from, and why is a curriculum important? ■■ Helpful information and tools 4 4 5 9 Learning with the IMYC ■■ Introduction ■■ The IMYC Learning Goals ■■ Personal dispositions: what kind of students are we helping to develop? ■■ International Mindedness ■■ What does it mean to be internationally minded? ■■ What is an International School? ■■ What is an International Curricullum? ■■ The IMYC types of learning: Knowledge, Skills and Understanding ■■ The IMYC Learning Structure and Process of Learning ■■ Assessment in the IMYC ■■ The IMYC Assessment for Learning Programme 11 11 11 Getting started: Implementing the IMYC ■■ Introduction ■■ What are the implications for stakeholders? ■■ What do leaders and teachers need to know? 22 22 23 23 Implementation timeline ■■ Begin with the end in mind: the IMYC Self-Review Process ■■ The stages of implementation 28 28 29 Appendix A: The IMYC Learning goals 31 Appendix B: Research into Learning ■■ References 52 57 Appendix C: Five Key Needs of the Adolescent Brain 58 13 14 14 15 16 17 18 20 21 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 1 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Welcome to the International Middle Years Curriculum Welcome to the International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC), a unique curriculum for students aged 11–14 years. Designed around the very particular needs of the adolescent brain, it helps to improve learning in three ways: academically, personally and internationally. As a teacher of Maths and Science in secondary schools and a parent of three boys (who have all safely survived their adolescent years, albeit not without the usual challenges and triumphs), I have always been aware that the ages 11–14 can be a very taxing and challenging time for students, teachers and parents alike. Students may exhibit such radical changes in behaviour and personality that we hardly recognise them! They may look for sensation, take dangerous risks, value the opinions of their peers above those of an adult’s, and disengage from learning and school. Not only do we believe that this period is a crucial stage in every student’s learning journey, we would go as far as to agree with the words of BJ Casey, Neuroscientist at Weill Cornell Medical College: “We’re so used to seeing adolescence as a problem. But the more we learn about what really makes this period unique, the more adolescence starts to seem like a highly functional, even adaptive period”. Jay Giedd, famous for his neuroimaging study of the developing brain, states that “the adolescent brain is not a ‘broken or defective adult brain’; it is exquisitely formed … to have different features compared to children and adults”. Through the IMYC, we to try to support these unique learning needs whilst students strive to make sense of their secondary school environment, themselves, and their changing needs and emotions, as well as keep up with the academic challenges of secondary education. We hear the most heart-warming stories from schools that use the IMYC, and we remain convinced that the IMYC will change the way that your students learn, prepare them well for the more formal stages of Secondary School, and keep them engaged in learning. Enjoy using it, and please share your stories and your experiences with us. Isabel du Toit Head of IMYC 2 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E What is the International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC)? The International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC) is a curriculum aimed at 11–14-year-old students, designed around the needs of the maturing adolescent brain. The IMYC inspires students during a time when many, overwhelmed by the combination of the transition from primary to secondary education and the changes in their bodies and brains, can become disengaged in their learning. Neurological research tells us that the brain is synthesising and specialising during adolescence. Consequently, middle years students need particular support organising and connecting their thinking and learning. This ‘fine tuning’ of the brain requires young people to make connections and make meaning of their learning like never before – in a ‘use it or lose it’ fashion. They engage most in learning when they can see the relevance of what they are learning about, and when they are actively involved in the process. The IMYC takes this into account and specifically addresses each of these learning needs. We recommend that you visit our website (www.greatlearning.com/imyc and IMYC Members’ Lounge) as often as possible. Ensure that you really make use of the ‘My Fieldwork’ page in order to tailor it specifically to your needs. The Members’ Lounge also gives you opportunities to meet and collaborate with other schools. Furthermore, as we are continually improving the IMYC –updating this Teachers’ Implementation File, adding and updating unit tasks, and sharing new information and ideas – it is worth checking up on any developments regularly. The IMYC endeavours to provide you with all of the practical help that you need in order to implement a truly learning-focused curriculum in your school, support the needs of the students of this very interesting, yet challenging, age group, and facilitate collaborative planning, Assessment for Learning, and improving learning in the classroom. We wish you well in your use and implementation of the IMYC, and we welcome you to the IMYC’s worldwide learning community. The Self-Review and Accreditation documents, which can also be found the Members’ Lounge, are very useful documents for schools that wish to implement the IMYC to its full power and potential, and we encourage you to use it to track your implementation progress and success from the very beginning, even if you do not intend to ever apply for a formal Accreditation. The Implementation Guide for the Assessment for Learning Programme is another very useful document available on the Members’ Lounge, and we recommend that you study it in detail in order to fully understand the IMYC view on assessment and the support that we provide to teachers, as well as what we expect teachers and schools to add to the materials themselves. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 3 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Teaching with the IMYC Introduction We believe that the purpose of teaching is to facilitate student learning in appropriate ways and that, whenever possible, this process should also be enjoyable for teachers. Teachers are likely to be more successful in helping students learn if they work closely with colleagues, parents and other members of each student’s community. The emotional, physical and social changes facing students at this age require particular nurturing and patience from all of the adults in their lives. Therefore, the more that adults work together, the more that they will be able to help students through this unique stage of their development. We believe that teachers should spend more time on thinking about and planning how to help individual students learn than on writing whole-school curricula. We have therefore developed examples of learning activities that teachers can use to help students to reach the Learning Goals identified in the IMYC. These activities – which have been developed by outstanding teachers, all experts in their fields – allow teachers to add their own interpretations whilst still enabling them to spend their precious time on doing what they enjoy and were trained for. As a teacher, you have a chance to make a difference to every student’s learning. You are, and always will be, one of the most important influences in the lives of the students that you teach. That is why teaching is so important and so challenging. Do a good job and you will have had a positive influence on the next generation – what an exciting challenge (and responsibility) we have! What does this mean? It means that you are in a position to help your students – not only to develop their knowledge, skills and understanding for your subject, but also determine whether the students that you teach will enjoy their learning or see their time in school as just as something to get through. It means that you have the chance to help them to develop their own identity whilst recognising that they live in a global community, as well as to increase the range of personal attributes that they will take with them into their later lives. At the very least, this means helping your students to see: ■■ How they can get along and how they can disagree in a constructive manner ■■ How they can be proud of their own national heritage and culture and, at the same time, be deeply respectful of the heritage and culture of others ■■ How they can begin to deepen their awareness and appreciation of the idea of the ‘other’ ■■ How they can live both independently and interdependently within and across cultures and countries The IMYC was designed to aid teachers in improving student learning, and it is structured around supporting five key needs of the adolescent brain. 4 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The curriculum begins with a set of standards or learning outcomes, called the Learning Goals, which clearly define what students should know or be capable of at this important period of their development. These form the foundation/skeleton of the IMYC, describing and summarising everything that we have found our international network of educators to agree that students should know, be able to do, and understand, in every subject covered by the IMYC. The IMYC contains Learning Goals and tasks for the following subjects: ■■ Art ■■ ICT and Computing ■■ English Language Arts (creative listening, speaking, writing and drama tasks for English) ■■ Geography ■■ History ■■ Music ■■ Physical Education ■■ Science (Biology, Chemistry and Physics) ■■ Technology As well as Learning Goals (though no specific tasks) for: ■■ Mathematics ■■ Additional Language (for Modern Foreign Languages) Where does good learning come from, and why is a curriculum important? Students learn what they learn from all kinds of places, people and experiences. Some of this learning is accidental; it just happens. Accidental learning takes place in schools as well as everywhere else. There are so many opportunities, both during breaks and recess and in the ‘busyness’ of the whole daily experience. However, schools are also places that are specifically set up to encourage and facilitate learning. A school is not really a school unless a great deal of deliberate learning takes place. Deliberate, planned learning is what schools are for, and that is the challenge facing all of us in the profession, including you and your colleagues. You are responsible for that deliberate learning. That is why you are so important. You are more important than the resources that you have, the buildings that you are in, the quality of your principal, head teacher or superintendent and, dare we say it, more important than your curriculum. However, a curriculum is one of your most important support systems. The IMYC has been written to help you be the best teacher that you can be and, even more importantly, to help your students to receive the best 21st-century education possible. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 5 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The IMYC contains many elements that are common to all good curricula. In preparing the IMYC, we set out to make those elements as accessible and as trouble-free to teachers as possible, without compromising on the primary goal of improving learning. As a teacher using the IMYC, you will need to be aware of the differences in the way that knowledge, skills and understanding are learned, taught and assessed (please see the Assessment for Learning Implementation File for more details). In order to facilitate optimum learning improvement, you will need to create multiple opportunities for students to practise skills throughout the three-year period of the IMYC, as well as provide sufficient time in the classroom for students to reflect on their learning. However, the IMYC also has some elements that, taken together, set it apart. These elements are: ■■ Rigorous and clearly articulated Learning Goals (see above) Because knowledge, skills, and understanding in all subjects are learned differently, taught differently, and assessed or evaluated differently, students, teachers, and others need as much clarity as possible if activities are to be learning-focused. ■■ International Mindedness We live in an interconnected and global world. The IMYC has the strongly-held view that the development of International-Mindedness is as important as Mathematics, Language Arts, History, Music, or any other subject. From the outset, we built into the IMYC rigorous opportunities for students to become aware of the parts of a bigger world that exist both independently of each other and interdependently with each other. ■■ Independence and interdependence As we developed the curriculum, the ideas of independence and interdependence have become important beyond International Mindedness. Consequently, the curriculum is now designed to ensure that students work both independently and, in groups of varying sizes, interdependently. Moreover, although students of the IMYC still study individual subjects independently, subject areas are often interlinked in a specific unit through the Big Idea. ■■ Engaging students aged 11–14 The International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC) is specifically designed to support the needs of the developing adolescent in ways that will improve the learning of 11–14-yearold-year-olds. The IMYC has studied – and continues to study – the latest neuroscientific research on how the adolescent brain learns; this facet of the curriculum is described in the appendix to the Self-Review and Accreditation Document. The appendix includes a resources section that, though it is by no means exhaustive, seeks to share the main easilyaccessible studies that were used to reach our conclusions. There are many changes that students aged 9–14 typically go through: −− Physical growth spurts −− The onset of puberty −− Change in the way their brains are wired (specialisation) −− Struggle for identity at home, at school and elsewhere 6 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E −− Stronger identification and affiliation with their peers −− Increased risk-taking and sensation-seeking −− Search for meaning A curriculum that is focused on helping students aged 11–14 engage with learning in new ways clearly needs to respond to this group’s unique nature. This is an important part of differentiated learning. The IMYC units of work For each of the three years of middle/secondary schooling, the IMYC provides ten units of work with learning activities for nine different subjects, each structured around a conceptual idea called the ‘Big Idea’. In total, this adds up to 30 units of work. For example, the first unit in M1 (designed for 11–12-year-olds) is based around the theme of ‘Adaptability’ and the Big Idea that will be used to interlink all learning in this unit is: “Adaptability is demonstrated by the ability to cope, alter or change with new circumstances or environments”. Based on the average teaching time available for each subject per week, collected from 20 schools that helped us to develop the first units, each unit was designed to be completed over the course of approximately six weeks. Consequently, for every year group, schools should choose approximately six units that they want to use from the ten available to them. In the IMYC, we call these year groups M1 (typically 11–12-year-olds), M2 (12–13-year-olds) and M3 (13–14-year-olds) in order to avoid any confusion between the different grading systems used in different countries. Interlinking learning through the Big Idea In recent years, neuroscientific research has informed us that the brain learns by making connections between brain cells/neurons. ; Accordingly, the formation of a constellation of neurons related to a particular concept or idea is sometimes referred to by neuroscientists and psychologists as a ‘chunk’ of information. Neuroscientists say that the brain learns ‘associatively’, meaning that it is constantly looking for patterns in order to link new information to previous learning. (See the appendix to the Self-Review document for more information and references) In primary schools, teachers often find these links for students and regularly highlight any links between the learning in different subjects. However, secondary teaching and learning is often organised into departments, resulting in students having the responsibility of finding their own links. The IMYC aims to help students to develop the habit of identifying these links through an abstract concept called the ‘Big Idea’. This helps students to interlink their learning during the six-week period and to develop multiple perspectives of concepts and ideas. The IMYC writers linked the knowledge, skills and understanding Learning Goals for their subjects to the Big Idea that they felt was most appropriate and natural, covering all of the subject Learning Goals in the ten units available for each year group. This helps students to link or associate subject learning and concepts easily to the Big Idea, making retrieval easier. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 7 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E SCIENCE MUSIC MATHS ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE HISTORY ART When people work together they can achieve a common goal GEOGRAPHY ENGLISH ICT D&T This structure requires all teachers to support the students in finding links to the Big Idea, even if the subject does not have specific tasks in the IMYC resources. The following are some examples of the Big Ideas from which teachers and schools can choose: 8 ■■ Balance (11–12-year-olds): “Things are more stable when different elements are in the correct or best possible proportions” ■■ Resilience (12–13-year-olds): “Success over time requires persistence” ■■ Challenge (13–14-year-olds): “Facing up to, or overcoming, problems and barriers increases possibilities in our lives” From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Helpful information and tools Mind maps The IMYC created a collection of mind maps (see the Members’ Lounge on the ‘Planning’ tab) in order to illustrate simply and usefully which learning goals will be covered in each unit in order to facilitate collaborative planning between teachers from different faculties. There are 30 mind maps in all, each of which provides a coherent outline of each unit. It identifies: ■■ The Big Idea ■■ Explaining the Theme: the subjects that will make a specific contribution to the unit and their interpretation of the Big Idea ■■ The subject-specific Learning Goals ■■ The kind of learning that students will engage in for each subject, so that they learn the specific Learning Goals and address the Theme and the Big Idea The online IMYC Route Planner All members of the IMYC have access to the online Route Planner on the Member’s Lounge. The Route Planner makes planning easy and efficient by providing a ‘drag and drop’ system that quickly organises the coverage in each unit over a full year. Assessment for Learning Programme Assessment of learning is important, as it helps teachers to find out whether and to what extent students have learned of the recommended material. The Assessment for Learning Programme contains detailed information and guidance on assessment in the IMYC. Other information Mathematics and the IMYC: You may have noticed that the IMYC units do not provide specific opportunities for students to learn Mathematics. However, the units do give students the chance to put some of their Mathematics into practice. There is a simple reason for this. In talking to teachers and schools during the planning phase of the IMYC, most told us that they had already invested heavily in a Mathematics scheme or programme of work that worked well enough in their school. Therefore, it was pointless producing Units of Work that contained material teachers were unlikely to use. Nevertheless, the Mathematics Learning Goals are important because, in addition to all of their other uses, schools can also use them as a checklist against which they can monitor the effective coverage provided by their separate scheme. We recommend that teachers still support students to link the content to the Big Idea, as well as to take part in the Entry and Exit Points. This will emphasise the need for students to notice connections in their learning in all subjects, not just the ones that happen to have related tasks in the IMYC. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 9 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Modern Foreign languages and the IMYC: As with Mathematics, the IMYC identified certain learning goals that were also common to the learning of a foreign language (see the Additional Language Learning goals). In this case, however, because of the sheer scope of all the different languages learned across the IMYC network, it was not practical to develop language-specific tasks. Similar to the above, we recommend that teachers still support students to find links between the content of their language-learning and the Big Idea, as well as to take part in the Entry and Exit Points. English Language Arts and the IMYC The IMYC approach to English Language Arts is specifically designed around Learning Goals that identify the developmental aspects of Language Arts. These relate to students’ ability to use their speaking, listening and writing as a means of communication and their reading as a means of research and pleasure. Consequently, the tasks were not developed to cover formal grammatical rules. When designing the tasks for English Language Arts for a unit, we specifically reduced the time needed to complete the set tasks in order to leave time for teachers to include their own tasks on grammar. 10 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Learning with the IMYC Introduction Learning with the IMYC is structured through six-week units, based around the concept of the ‘Big Idea’. An example is: “Things are more stable when different elements are in the correct or best possible proportions”. ■■ Students study nine different subject disciplines in their subject classes, which include subject-specific assessment. Importantly, they link the learning in their different subjects through the Big Idea, considering what they are learning from a personal and global perspective. ■■ They reflect regularly by responding to structured questions. This process is called ‘Reflective Journaling’, or just ‘Journaling’, and it is designed to help students to formulate and develop a personal and conceptual understanding of the subject knowledge and skills that they’re learning about, based around the Big Idea. ■■ At the end of each six week unit, as part of the Exit Point, students then work individually or in small groups to present a piece of work to their classmates, parents or whole school. This will usually be in the form of a Media Project that reflects their own thinking on the Big Idea. This provides students with the opportunity to express themselves through a creative medium, as well as to practise and improve their presentation and technological skills. ■■ Students in IMYC schools all over the world are producing powerful, thought-provoking and creative media projects, inspired by a Big Idea, on such topics as the Everglades, art in Chicago, cyberbullying and global warming. The IMYC Learning Goals The way that the IMYC defines the Learning Goals (or the learning that we think students need) may differ from the way that other curricula define their goals in some very important ways. This is due to the fact that we hold the following beliefs: ■■ There should be a distinction between goals for knowledge, skills and understanding ■■ Learning must respond to the current and future personal needs of students. For example: the particular needs of the adolescent brain, their future career needs, and the needs of the varied societies and cultural groups in which they are likely to play a part. ■■ Learning needs to be proactive, in the sense that students must actively engage with their learning. For students aged 11–14, this means that learning which is relevant to the future must be placed in a context that is meaningful and connected to their present lives, and that is relevant to their particular stage of development. ■■ Students need to share the responsibility for their learning with their teachers, parents and caregivers. The proportion of responsibility that each stakeholder bears will depend on the From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 11 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E age and characteristics of the student. Nevertheless, learning must be constructed in such a way that, by the end of the middle years (11–14), students feel increasingly confident about taking responsibility for their own rigorous learning. ■■ You will find that in the Assessment for Learning Programme, for example, we provide students with rubrics outlined in appropriate language, in order to facilitate them take ownership and responsibility for their learning. ■■ The IMYC has a simple but comprehensive learning structure. Everything is based on clearly-defined Learning Goals that lay out the subjects, personal and international knowledge, skills, and understandings that students need at different stages of their early secondary or middle years education. The IMYC Learning Goals Subject Learning Goals The subject goals cover the knowledge, skills and understanding that students should learn in Language Arts, Science, History, Geography, ICT & Computing, Technology, Music, Art, PE. Tasks that enable students to reach these learning goals are built into the units of work supporting students to link their learning through the Big Idea and allowing students to talk about their learning through multiple perspectives. Personal Learning Goals The personal goals refer to those individual qualities and dispositions we believe students will find essential in the 21st century. There are eight IMYC personal dispositions: enquiry, resilience, morality, communication, thoughtfulness, co-operation, respect and adaptability. Opportunities to experience and practice these very specific dispositions built into the learning tasks within each unit of work. International Learning Goals The IMYC is unique in defining learning goals that help students move towards an increasingly sophisticated national, international, global and intercultural perspectives on the world around them, whilst developing the capacity to take action and make a difference. The IMYC Learning Goals are defined for each subject that contributes to one or more of the IMYC units. The IMYC states explicitly which of the Learning Goals will be covered in each subject section of each unit. One of the features of the IMYC is that activities have been designed to support only those Learning Goals that can effectively be linked to the Big Idea for the unit. 12 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E By using the Learning Goals, teachers will know the broad learning outcomes for their subject within each unit. They will be able to check if the Learning Goals that they ‘need’ to include are being covered within your school’s choice of units. The Route Planner (available in the IMYC Members’ Lounge) will do this automatically, and each teacher will then be able to make their own decisions about how they will cover any that are outstanding. Every IMYC Learning Goal is a specific statement of what students should ‘know’, ‘be able to do’, or develop an ‘understanding’ of, for specific subject disciplines, International Mindedness and personal dispositions. See the Members’ Lounge for a full list of all the IMYC Learning Goals. ■■ Subject Learning Goals: The IMYC contains Learning Goals for each subject of the curriculum. When defining the subject Learning Goals, we looked at curricula from many different countries around the world. The Learning Goals of the IMYC are broadly in line with most of those curricula of the appropriate subject discipline. ■■ Personal Goals: The IMYC has eight personal dispositions (attributes or skills): adaptability, communication, cooperation, enquiry, morality, resilience, respect and thoughtfulness. Efforts towards developing these personal qualities and learning dispositions should be reflected in the whole curriculum and in all other aspects of school life. ■■ International Goals: The IMYC has written a set of international goals, which teachers are encouraged to develop consistently and at every opportunity. See the Members’ Lounge for the document, ‘Global issues addressed in IMYC units’, for a summary of global issues covered by tasks in the IMYC. Personal dispositions: what kind of students are we helping to develop? All of the learning that students experience in a school defines, in some way, the kind of person that that school is helping to develop. Schools that ask their students to sit in rows, mainly listen to their teachers, and do not allow them to make any decisions of their own, will inevitably develop a different kind of person to one developed in schools that take a different view of teaching and learning. The IMYC believes that 21st century students are most likely to succeed if they: ■■ Have learned appropriate knowledge, engaged practically in learning appropriate subject and life skills, and have been able to reflect in ways that enable them to develop their understanding of key issues and ideas ■■ Are able to see the connections between the different kinds of learning in which they engage and the subject discipline of that learning, and are able to see that the world exists independently and interdependently at the same time ■■ Know what it is to learn rigorously, habitually reflecting on their learning and embracing the struggle to improve ■■ Are engaged and excited by their learning – dare we say that they enjoy their learning? – so that they want to continue to be learners throughout their lives From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 13 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E ■■ Are able to appreciate the views and ideas of others – in their own group, in the wider society in which they live, and across the world ■■ Have and develop a number of key personal attributes and skills (dispositions) that enable them to respond to the world that they live in Throughout their study of the IMYC, and all other aspects of their lives, students learn the personal and social skills that they need in order to develop into healthy and productive citizens of the world. Students learn about the personal qualities of: ■■ Enquiry ■■ Adaptability ■■ Resilience ■■ Morality ■■ Communication ■■ Thoughtfulness ■■ Cooperation ■■ Respect Efforts towards achieving these goals should be reflected in the whole curriculum and in all other aspects of school life. To a large extent, they are assumed in the subject goals, so these Personal Goals are, in effect, largely a summary of the personal outcomes of student learning. By their nature, Personal Goals are not age-specific. They apply to students – and adults – of all ages. International Mindedness As the principle of International Mindedness forms such an integral part of making the IMYC a truly international curriculum, we feel it warrants its own section in the file. What does it mean to be internationally minded? In an interconnected global society, it is often claimed that one of the personal dispositions that students need to survive in a changing world is to be ‘internationally minded’, usually for the following reasons: 14 ■■ Future jobs are increasingly likely to be found away from one’s home country ■■ The companies that students will work for may well be driven by cultures other than one’s own culture ■■ Whether for travel, work or leisure, we will all increasingly come across different cultures ■■ Most of the world’s major problems are only going to be solved through international cooperation From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E All of the above points make for a compelling argument. However, what is International Mindedness, and what does it mean for students, teachers, and curriculum makers? At the simplest level, we might say that it is about being at ease with people from other cultures and with cultures different from our own. In fact, this may well do as a working definition. There are complexities, of course, and much of the discussion focuses around the level at which we can describe someone as being ‘at ease’: ■■ Is it the ability or willingness to live alongside, but not integrate? ■■ Is it only when we are able to fully integrate into another culture? ■■ Is it only when one can fully empathise with people from different cultures? There is also the issue of how crucial language-learning is to the development of International Mindedness: ■■ Is it possible for me to ‘get’ cultures different from my own if I don’t speak the language that plays a large part in revealing that culture? ■■ If it is important, what level of language proficiency do I need to have? Howard Gardner has said that the process of human development is “a continuing decline in egocentricity”. In other words, we develop from the tiny baby crying in the pram to the ‘terrible twos’, when we clearly demonstrate our awareness of the ‘other’, through parallel play with children of our own age to our first ‘real’ friendship, and so on. Gardner’s developmental ideas help us to see that International Mindedness – dealing as it does with all of the differences within our own cultures magnified by the context of other cultures – is somewhere towards the end of the process of our declining egocentricity. It also helps us to realise that most 11–14 year-olds can only be at a relatively early stage of International Mindedness although, importantly, they are still on the pathway of a growing sense of the ‘other’ and a declining sense of their own egocentricity. However, it is worth remembering that, as they struggle to make meaning for the first time, it often seems as though a rising sense of their own egocentricity comes back into play for a whilst. It is this growth of International Mindedness and decline of egocentricity that we need to think about developing in schools. We need to think about helping our students to start by working from the differences between individuals, families and other groupings familiar to each student, and then about how to use these experiences to help them to come to terms with the broader and more profound differences and similarities between their culture and those of others who live in a world that is quite different (but no worse) to their own. What is an International School? Conventionally, a common answer to this question has been along the lines of “a school with different nationalities” or “a school that is not situated in its ‘home’ country”. These answers make a sort of sense on a superficial level. However, they don’t go deep enough. It is more From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 15 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E helpful to think about ‘internationally-minded’ schools, i.e. schools which build into the fabric of their work opportunities for their students to experience different points of view and different cultural approaches on an increasingly larger scale. Internationally-minded schools encourage a growing critical awareness that enables students to increasingly see themselves and others as ‘similar, different, but equal’. This ‘similar, different, but equal’ approach is anything but woolly. It requires getting under the skin of our similarities and differences and appreciating that we may be similarly or differently ‘wrong’ as well as ‘right’. Schools that are able to do this have their own characteristics. They demonstrate many of the Personal Goals of the IMYC in their own daily practice. They are respectful, moral, communicative, collaborative, and more. They work to create a culture in which ‘similar, different, but equal’ is at the heart of everything that they do. What is an International Curriculum? In the IMYC, we have always claimed that we have done everything we can to embed opportunities for students to develop International Mindedness into the curriculum. In practice, this means that: ■■ Your students will work on their own, in pairs, in groups, and with the whole class, so that they experience a different range of perspectives and intrapersonal and interpersonal experiences on a regular basis. ■■ Your students will always learn through the immediate experience of their own culture and environment, but not exclusively so. The IMYC provides many opportunities for your students to look at issues through the lens of cultures and environments that are not their own. ■■ The IMYC provides opportunities through its website and the Members’ Lounge for your students to engage with students from other cultures around the world during their work. ■■ Your students are asked to think reflectively throughout the IMYC in order to foster their developing understanding. These reflections are fostered not only through the journaling that students do in each subject section but, critically, through the Exit Points in which your students work collaboratively to represent their understanding of the Big Idea. Many of the Big Ideas are themselves important elements of developing International Mindedness. ■■ Your students will be taught in a way that allows them to develop the personal qualities of enquiry, adaptability, resilience, morality, communication, thoughtfulness, cooperation and respect. These qualities should be reflected not only in the whole curriculum, but also in all other aspects of school life. The IMYC believes that International Mindedness is so crucial to the 21st century and the personal and collective roles that our students will play out as they live their own lives that we have given it the same prominence as we give Mathematics, Language Arts, and the other subjects. We look forward to working with you and learning from you as we continue to create opportunities for your students to develop further. 16 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The IMYC types of learning: Knowledge, Skills and Understanding The IMYC Learning Goals – academic, personal and international – form the foundation/ skeleton that the IMYC tasks were developed around. In order to fully understand the Learning Goals, it is important to know that the IMYC believes that there are three types of learning: knowledge, skills and understanding. Each has their own distinct characteristics that impact on how they are planned for, learned, taught, assessed and reported on. We believe that differentiating between them is crucial to the development of students’ learning, and we therefore separate them in the Learning Goals. Therefore, the implications of these differences are far-reaching and deserve proper consideration: 1. Knowledge: In the IMYC, ‘Knowledge’ refers to factual information. Knowledge is relatively straightforward to teach and assess (through quizzes, tests, multiple choice, etc.), even if it is not always that easy to recall. Knowledge is continually changing and expanding, which creates a challenge for schools that have to choose what knowledge students should know and learn in a restricted period of time. The knowledge content of the IMYC units can be adapted to the requirements of any national curriculum. 2. Skills: In the IMYC, ‘Skills’ refer to things that students are able to do. Skills have to be learned practically and need time to be practiced. The good news about skills is that the more you practise them, the better you get! Skills are also transferable and tend to be more stable than knowledge in almost all school subjects. For example, although the equipment that scientists use may have changed over the past 200 years, the skills needed remain largely the same. As we learn skills, we make a progression and, for the IMYC, this progression takes the student from Beginning, through Developing, to Mastering. Note that even ‘Mastering’ is not ‘mastery’. The reason that concert pianists and professional golfers, for example, keep practising is that there is not an end point to the development of skills. 3. Understanding: The IMYC agrees with the definition used in the famous book Understanding by Design (Wiggens and McTighe, 2005) and sees understanding as “the creation of a coherent schema through a combination of the acquisition of knowledge, the practice and continual development of skills, and extended time for reflection”. It is often experienced as a ‘aha’ moment – the moment in learning that we all strive for – but it goes far beyond that, as learning always keeps on developing. None of us ever ‘gets there’, so you cannot teach or control understanding. The IMYC unit tasks include journaling questions that structure the students’ reflection on their learning and aim to support developing understanding by linking back to the Big Idea. This creates the opportunity for students to develop both subject and personal understanding. The Exit Point/Media Project allows students to demonstrate their understanding and share the personal meaning that they have made of their learning. We believe knowledge, skills, and understanding act as a ‘wholearchy’, rather than a hierarchy, with each different type of learning including and transcending the other. However, each does have its own distinct characteristics, and it can be very powerful to ‘signpost’ to students what kind of learning they are experiencing and what the implications of this are in the classroom. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 17 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The IMYC Learning Structure or Process of Learning Exit Point Assessment for Learning Entry Point The Big Idea Reflective Journaling Knowledge Harvest Learning Activities The structure of an IMYC unit All of the 30 units have a consistent structure according to the IMYC process of learning. It is important that learners do not just experience the structure and process of the IMYC, but also that they understand why they are learning in this way. The subject tasks in each unit have the following elements in common: ■■ The Big Idea forms the basis of the unit and is the concept that all learning will be linked to ■■ The Entry Point is an introductory activity for students in each unit of work, providing an exciting introduction to the work that is to follow. Entry Points can typically last from one hour to a full day, depending on the activity and the school. In order to set the scene for interlinking learning through the Big Idea, Entry Points should ideally be done with the whole year group. Preferably, teachers will plan for Entry Points together, in order both to develop the habit of collaborative planning and to foster a creative environment for the following weeks that will be spent on the unit. (See the Members’ Lounge for examples of Entry Points that schools have used) ■■ The Knowledge Harvest is the first formal learning activity in the IMYC Learning Cycle. The purpose of the Knowledge Harvest is to give students an opportunity to share and display what they already know about the Learning Goals within each subject section, the skills that might be learned, and the deepening understanding that they may already be bringing with them. Each subject teacher will conduct a Knowledge Harvest specific to their class, set in the context of their own subject. The Knowledge Harvest can be done in any variety of ways. For example: through class discussion with the teacher, through discussion between groups of students and feedback to the teacher and class, through knowledge tests or simple skills-based activities, etc. 18 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The results of the Knowledge Harvest can be recorded in many different manual or electronic forms, for example as a mind map, so that students can visibly see their learning growing as they move through the unit. The Knowledge Harvest will happen in each class as the first formal learning activity, and it is typically the first task for a subject. ■■ Subject tasks: Each unit of work has subject-specific tasks that teachers can use and adapt to facilitate the students’ learning in order to reach the specific unit’s subject Learning Goals. These tasks are designed around a ‘concept’ in the subject and are not designed to be ‘lesson plans’ or to take the same time to finish. For example, Task 1, which is normally a Knowledge Harvest, can take just one period (or even half of one) to complete, whilst a task designed around practising a skill or discovering something could take more than one period. Teachers that design their own tasks for their subject for whatever reason should ideally follow the same task structure and teaching practice. Additionally, each IMYC subject task has research activities and recording activities: −− Research Activities: Research activities will always precede recording activities. During research activities, students use a variety of methods and work in different group sizes to research a topic, find out information, or practise certain skills. The structure was designed to allow students to be exposed to enquiry-based learning and take responsibility for their own learning. −− Recording Activities: During the recording activities, students interpret the learning that they have had and have the opportunity to demonstrate, share and explain their learning in different ways ■■ Reflective Journaling: As above. The IMYC sees understanding as the “creation of a coherent schema through a combination of the acquisition of knowledge, the practice and continual development of skills, and extended time for reflection” In every unit, the last activity for a subject contains a set of journaling questions that formally support student reflection. These are merely examples of questions that can be used and should be adjusted to the language proficiency of your students. Some of the questions may be around personal dispositions, whilst others will foster International Mindedness by encouraging students to consider the perspectives of themselves, their families and others throughout different activities. When adapting the questions, teachers should follow the structure of questions about: −− Subject concepts −− Links to the Big Idea −− Making personal meaning of their learning (dispositions and International Mindedness) Throughout each unit, students participate in daily or weekly journal writing. The primary purpose of journal writing is to provide some initial reflection time for students to consider the unit’s Theme and Big Idea through directive and orienting questions driven by the activities in each unit. Journaling can be done as class activity, as homework, or during homeroom or advisory times, and it may help students to organise their Exit Point project. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 19 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E ■■ Exit Point: This is a key element in developing understanding over the three years. Each of the IMYC units is written to be completed in about six weeks. During the sixth week, teachers and students come together for an extended period of time in a final formal opportunity for students to demonstrate the understanding that they have developed through a combined project, often called a Media Project. Over the six IMYC units within a year, students will conceive, design and produce six Exit Point projects. The hard work is in the thinking and planning that is at the heart of the Exit Point. They could be involved in: ■■ Reviewing and reflecting on their personal learning in subjects, on meaning made during the six weeks, and on links to the Big Idea ■■ Deciding how they can represent that meaning within the context of the particular Media Project being attempted. The Media Project doesn’t necessarily have to be modern media like Videos, Podcasts, Web Documents or PowerPoint Presentations. It could be debates, dramas, extensive writing projects, magazine articles, cartoons, or many more. As long as it is an engaging hands-on opportunity for students to demonstrate their learning and deeper understanding in: −− Subject concepts −− Connecting subject learning through the Big Idea −− Making personal meaning of their learning −− Creating their individual or group project and publishing it, where appropriate. As each student will experience their learning in a unique way, this activity will be individual to the understanding each learner gained on a personal level, even if the project is developed in a group. Often it will be generated by the ideas and deeper understanding that is cultivated through the weekly journaling. Assessment in the IMYC We believe that students don’t always learn what we planned for them to learn, so it is crucially important for us to figure out and gather evidence of their learning. The goal of assessment should always be to help students to improve their learning, which is why we focus on Assessment for Learning. This is true whether the teacher assesses knowledge or skills, or evaluates understanding. Gaining knowledge, skills and understanding are all different learning experiences, so we believe that they should be taught differently and assessed differently. 20 ■■ The IMYC does not provide examples of knowledge assessment (tests or exams) as it was designed to be a flexible curriculum, allowing teachers to adapt both content and assessment practices to suit their school, country and students. It is expected that schools will define and implement their own knowledge assessment tools, but still assess for learning, rather than for reporting. ■■ The IMYC supports skills tracking and assessment through the IMYC Assessment for Learning (AfL) Programme. Please refer to the AfL Implementation File and the different From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E resources (rubrics and learning advice) for subjects in the ‘Assess’ tab on the Members’ Lounge for more details. ■■ The IMYC supports students to develop their understanding through the process of ‘Reflective Journaling’ and to demonstrate their understanding through the Exit Point. Please see the AfL Implementation File for more information about how to do this. It will require careful planning to make sure that students’ understanding progresses during the six-week period of learning – whilst avoiding falling into the trap of assessing students’ skills – and never moving on to the evaluating understanding developed. Proper systems for giving feedback – whether it is coming from teachers, peers or parents – need to be developed by every school. There are some examples of ways schools have used these to ensure rigorous feedback on the ‘Teach’ tab on the Members’ Lounge. The IMYC Assessment for Learning Programme The IMYC AfL Programme helps to track students’ skills over time, enables and encourages peer assessment, and provides tools and guidance to help you to improve your students learning, rather than simply recording their skill level. Please see the AfL Implementation file for resources and more information. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 21 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Getting Started: Implementing the IMYC Introduction In the following section, we will give some advice to leaders and teachers as to how to implement the IMYC successfully in your school. As more and more schools become IMYC members, we are developing more knowledge and understanding of the issues connected with introducing the IMYC into your school. This section of the file looks at some of those issues and offers advice based on the many conversations and in-school experiences we have had with member schools. Implementation of a new curriculum is a major change for many schools, and the planning process and the leading and managing of change are essential ingredients for success. The model below shows the six stages of implementation: 1. Discover the issues 2. Address the issues 3. Plan professional learning and development opportunities 4. Implement 5. Gather feedback 6. Analyse feedback 7. Begin a refined implementation process Discover the curriculum issues in your schools Begin again to deepen the process Address the issues Plan professional learning and development opportunities Analyse feedback Gather feedback 22 Implement From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E What are the implications for stakeholders? What will stay the same? 1. School structure: The IMYC was designed to be used with a ‘normal’ secondary school structure, i.e. subject-specific teaching and learning, allocating the same amount of time to each subject as in a more traditional curriculum. 2. Subject teaching: Teachers are still responsible for ensuring that the students know what they should know, are able to do what is expected, and understand the necessary subject concepts and principles that they will need for the next phase of their learning. This includes making sure that they learned what we planned for them to learn. The IMYC supports teachers with the AfL Programme to track subject skills for every year and over the three years. 3. Reporting to parents and stakeholders: The IMYC does not involve itself in how schools choose to report to parents on their child’s progress, as different countries expect different kinds of reporting. We encourage schools to use all assessment for improving students’ learning (subject, personal and international) and the AfL Programme enables schools to report on skills progression in their preferred way. What may need some adjustment? 1. Time for teacher collaboration: The IMYC encourages schools to set apart time specifically for teacher collaboration and planning. For example, enough time to plan together for Entry and Exit Points should be built into your schedule, and teachers should agree on how they will use and implement Reflective Journaling. 2. Time for students to take part in activities around Entry Points, to reflect on and make personal meaning of their learning, and to plan and present their Exit Points: Many schools make use of pre-existing group activities in the timetable, for example assemblies, tutor times, etc. What do leaders and teachers need to know? Advice for school leaders ■■ Make sure that you understand the principles that the IMYC is built on and that you agree with them. This is especially important regarding the belief that improving student learning should be the main goal or – as it is called in the Looking for Learning Toolkit – the ‘hedgehog concept’ of the school. This means that improving student learning is the principle around which we make all our decisions and drives all our actions. ■■ Appoint an ‘IMYC Curriculum Leader’ that will drive the implementation of the IMYC. It is important that this person is empowered to implement the necessary changes, as well as to have the capacity to support teachers with aspects of these changes. ■■ Be aware of the change in mindset that some teachers may experience in planning for student learning, i.e. planning from a learning goal and not from content. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 23 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E ■■ Ensure rigour. Use supporting tools, like the Route Planner, to ensure that learning is sufficient and appropriate for all students. . ■■ Allow enough time for rigorous planning. It is essential that teachers have the opportunity to plan collaboratively. Our experience is that it can be a very creative process when a whole group of teachers plan together for Entry and Exit Points, and it also shares the responsibility between them. ■■ Invest in professional learning days at the school. We recommend allowing at least two days to support all teachers in understanding the principles, goals, and philosophies behind the design of the IMYC, and why it is structured in a particular way. ■■ Provide time for students to plan and present their Media Projects to an audience, take part in the Entry Points, and reflect on their learning. The IMYC has developed systems and tools that will support the successful implementation of the IMYC, of which this document is the first. Other very important documents and tools are: ■■ The IMYC Self-Review Process: The IMYC Self-Review Process is now available for all member schools to help with improving learning in their school. It has been written in close collaboration with IMYC schools, and will help schools to embed the nine key principles of the IMYC – the ‘Bottom Line Nine’. We believe that they are the nine nonnegotiables that underpin the successful implementation of the IMYC. The IMYC SelfReview Process should become a school improvement tool from the beginning of the IMYC implementation, as this will ensure that the IMYC is much more than just a curriculum. It is a philosophy, pedagogy, and process that can help learners, teachers and the community to continually focus on improving learning ■■ The IMYC Members’ Lounge: This is where schools can find everything that they need, including the IMYC Learning Goals, the subject tasks, Assessment for Learning rubrics, and the Route Planner for subject planning. ■■ The AfL Implementation File: This file is available on the Members’ Lounge and clearly sets out IMYC views on assessment and associated resources. Specific Advice for the IMYC Curriculum Leader: 24 1. Take responsibility for leading the IMYC: Make sure that you lead and support teachers to plan in a rigorous way in order to ensure full subject coverage, support the needs of the adolescent brain, take responsibility for the students’ learning (subject, personal and international), and assess students’ learning. 2. Choose your units: Decide how many units you plan to use over a year, and choose the ones you want to use for every year group. Our experience is that it is a good idea to involve teachers in this process. Once the units and the order have been agreed, the IMYC Curriculum Leader should ‘publish’ the route plan that the school will use. This then becomes a ‘fixed’ plan for the year. We don’t recommend changing units through the year as it may undermine rigorous planning. 3. Spend time with all teachers: Support them with planning and implementation. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Advice for teachers 1. Plan the learning for your subject for the whole year We recommend that teachers plan for the IMYC on a yearly basis for each age group, and then plan for each unit in more detail after that. We have designed a simple flow-diagram to illustrate the process, which includes the necessary steps to ensure coverage in a specific subject, planning opportunities for assessment, and the planning of activities to help students to achieve the relevant Learning Goals. Subject Planning for the IMYC Plan for the whole year Choose your six units for the year group Repeat for your country’s national curriculum Draw a report Which IMYC Learning Goals are not covered? Choose the Big Idea that links easily to the IMYC Learning Goals not covered Repeat the process until you have allocated all the IMYC Learning Goals to a Big Idea Make a note Remind yourself to adjust the tasks in the unit to reach this goal Plan for a unit Make sure you cover the goals you planned for Adjust the unit tasks or create new ones Remember to link to the Big Idea and help students reflect on their learning Help the students learn 9 Now plan for assessment How will I know that students learned what I planned for them to learn? From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 25 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E When referring to the diagram: ■■ Decide on the units that you will be using over the year for the relevant stage (M1, M2 or M3) using the IMYC Route Planner. This will provide an overview of when and where the different IMYC Learning Goals are and are not covered. For the Learning Goals that are not covered by your choice of units, study the Big Ideas and identify which of these naturally link to the missing Learning Goals. ■■ Add any missing Learning Goals to the subject goals covered in that particular unit, and make a note to develop or adjust tasks to reach this goal ■■ Cross-reference the IMYC Learning Goals with your national or local requirements. Any learning goals that are not covered can be added to the most appropriate units in the same ways as above. This will provide you with a detailed annual plan of which Learning Goals will be covered and in which unit over the year. ■■ Plan for your range of different assessments, identifying the opportunities within different units for you to make sure the students have learned what you had planned for them to learn 2. Plan for Assessment: how do we know that the students have learned what we planned for them to learn? Once you have identified the different Learning Goals for your subject, it is important to plan for assessment over the whole year. The IMYC believes that knowledge, skills and understanding are very different learning experiences, or learning types, and should therefore be planned for, taught, learned, assessed and reported on differently. Assessment needs to be balanced but rigorous in order to ensure that the students have learned what we intended. 26 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The diagram below illustrates the processes that you may want to follow to ensure this happens. Plan learning and identify the Learning Goals that you will assess. Knowledge (K). Skills (S). Understanding (U). KNOWLEDGE Plan when exams and tests will be set for your subject to assess the knowledge Learning Goals covered in the KNOWLEDGE Record, track and report ‘performance’ in line with your school systems. The IMYC Online Assessment Tracking Tool, developed in partnership with Classroom Monitor, will also be able to SKILLS Plan for skills practice and opportunities to assess and track progress in each key skill using the IMYC AfL rubrics. SKILLS Record, track and report student progress across beginning, developing and mastering through M1–M3 using the IMYC Online Assessment Tracking Tool, developed in partnership with SKILLS Create scoring rubrics for task specific activities. Track and report with school based system or the IMYC Online Assessment Tracking Tool, developed in partnership with Classroom Monitor. UNDERSTANDING Plan to evaluate Exit Points. How will you evaluate personal understanding linked to the Big Idea? UNDERSTANDING Peer and teacher feedback. Used to inform discussion with students and parents of the students’ personal understanding gained. 3. Plan your first unit (lesson planning) Having ensured that students will have the opportunity to achieve all of the Learning Goals and outcomes that you have identified, and having considered how you will know whether the students have learned what you planned for them to learn, it is time to plan the activities that will facilitate these. Use the tasks provided in the IMYC units as they are, or adapt them to the country or school’s needs. Teachers may have to write one or two tasks that will cover some of the country’s specific statutory learning goals or standards. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 27 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Implementation timeline Begin with the end in mind: the IMYC Self-Review Process The end of implementing the IMYC – or at least, the first end – is probably about three years away. We developed the IMYC Self-Review Process in order to give schools clear direction of the aims of the IMYC. After three years of successful IMYC implementation, we should be seeing the following: ■■ Students’ learning will have improved, their personal qualities developed, and their international awareness and understanding will be greater than it might have been otherwise ■■ Teachers will be using a variety of classroom strategies, alongside the latest research into learning, to optimise the conditions for learning in their classrooms ■■ The IMYC will have become embedded in the school. It will be the focus of much teacher talk, parent interaction, and pride. It will represent ‘the way that we do things around here’; the culture and ethos of the school. ■■ Parents and board members will have a high degree of confidence in the support the IMYC provides to teachers and leaders However, getting there takes time and planning. We advise schools to use the IMYC Self-Review Process – available to download from the IMYC Members’ Lounge – as soon as they start implementing the IMYC. This gives all stakeholders – whether learners, teachers, leaders or members of the community– a view of the final vision. It helps schools to embed and develop the curriculum across nine key areas of the IMYC (the ‘Bottom Line Nine’). Michael Fullan’s three key lessons of change The Canadian educator and writer, Michael Fullan, is a well-known expert on leading and managing change in education. His seminal book, Leading in a Culture of Change (Fullan, 2001), has been used by schools all over the world to help them to lead the complexities of major change in their schools. It is worth keeping three of his lessons in mind throughout the implementation process, as they are likely to prepare you well for leading change, even through the frustrating times. 28 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E They are: ■■ Expect an implementation dip However much people want something to happen, the difficulty of introducing something new compared to what we were familiar with can, at some point, cause a downturn. The trick is to work through the downturn towards the point when things start to improve. Grumbles in the early stages are not an indication of failure – they are normal reactions to change. ■■ If something can be misunderstood, it will be If students construct their own knowledge and understandings, then so do teachers, leaders, learners and the community. Keep in mind that everything new has to compete with everything that has gone before it. It is unlikely that colleagues and others are going to understand everything first – or even second time – however well-planned your message. ■■ Ready ... Fire ... Aim Fullan reminds us that the traditional Ready ... Aim ... Fire is fine when issues are simple. But when issues are complex, change is only possible by continual reference to a feedback loop of information, followed by refocusing. In practice, as Fullan advises, be as ready as you can, and then begin. Don’t wait until you have crossed every ‘t’ and dotted every ‘i’. It will never happen. Begin, get feedback, refocus, and begin again further down the track. Or, as Samuel Beckett the playwright once put it: “try, fail, try again, fail better”. The IMYC Self-Review Process can be a great help as a tool to be used in this feedback loop. By encouraging all stakeholders in the schools to reflect on where they are currently (‘Beginning’, ‘Developing’ or ‘Mastering’) across the nine key criteria of the IMYC (the ‘Bottom Line Nine’), it can help them to decide together on which areas they need to concentrate on as a school. It has been used by many schools as a tool for them to plan their short-, medium- and long-term school improvement plans successfully. The stages of implementation 1. Before implementation ■■ Make sure that all of the stakeholders in the school – teachers, leaders, parents, students, etc, – are provided with information about the IMYC, including the philosophy behind it and its practical implementation. ■■ Allow enough time for teachers to do rigorous and collaborative planning. ■■ Invest in professional learning days at the school. We recommend at least two days to support all teachers in understanding the principles, goals and philosophies behind the design of the IMYC, and why it is structured in a particular way. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 29 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 2. The first full year During this first full year, we advise leaders, including Curriculum Leaders, to visit classrooms as often as possible in order to support teachers during the implementation process, collaborating with them to ensure that the philosophy, pedagogy and process of the IMYC is in place. ■■ Teachers should increase their knowledge and understanding of the philosophy behind the IMYC, and practise their skills of implementing the IMYC Process of Learning. For example: linking all learning to the Big Idea, helping students to develop (or maintain) the habit of looking for links in their learning, making personal meaning of all learning (subject, personal, and international, etc). ■■ Students should be supported to take personal responsibility for their own learning and progress. ■■ By this stage of using the IMYC, your community will be hearing about the IMYC from the students. Near the beginning of this school year, hold a meeting for the community, and support any families starting later in the year by running follow-up meetings. Do not try to do too much at any single meeting. Make sure that the main focus is on improving learning. When the members of the community cannot attend these meetings, make sure that your newsletters and school website continue to contain regular mentions of the IMYC and the learning that is taking place. 3. Year 3 and onwards – becoming more focused on improving learning By Year 3, everyone in the school should be getting used to the philosophy, pedagogy and process of the IMYC. Implementation, as we know, is a continual process, so there are still new things that you can do in Year 3 to continue this process. For example, think about how to introduce new board members, colleagues and families to the IMYC. We encourage schools to reflect on the IMYC and its implementation continuously, but the third year might be the opportunity to reflect on applying for formal accreditation for the school using the IMYC Self-Review Process. Accreditation can be an excellent opportunity for teachers and leaders to share their learning with other schools. 30 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Appendix A: The IMYC Learning goals Part 1: Subject learning goals 1. ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE/MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGE Students will: 1.1 Know that foreign language learning enhances and reinforces their knowledge of other disciplines 1.2 Be able to communicate, ask for and give information and opinions, express feelings and emotions, and share preferences 1.3 Be able to understand and interpret written and spoken language on a variety of topics 1.4 Be able to present information, concepts and ideas to an audience of listeners or readers on a variety of topics 1.5 Be able to use the language both within and beyond the school setting 1.6 Be able to show evidence of becoming lifelong learners by using the language for personal enjoyment and enrichment 1.7 Develop an understanding of the relationship between the practices and perspectives of the culture studied 1.8 Develop an understanding of the nature of language through comparisons of the language studied and their own 1.9 Develop an understanding of the concept of culture by comparing and contrasting the culture of the language studied and their own 1.10 Develop an understanding for the distinctive viewpoints that are only available through the foreign language and its cultures 2. ART Students will: 2.1 Know that the study of art is concerned with visual, tactile and personal expression used to share and express emotions, ideas and values 2.2 Know the contributions and impacts of various artists in different countries and how their work influenced or was influenced by society 2.3 Know how art, history and culture are interrelated and reflected through one another over time From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 31 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 2.4 Be able to recognise influential artists from particular countries, genres or periods and the pieces of art they produced 2.5 Be able to evidence how artists, craftspeople and designers from a variety of traditions from around the world use materials, forms and techniques to express their feelings, observations and experiences 2.6 Be able to use the elements of art and principles of design to discuss and critique works of art showing understanding, respect and enjoyment as appropriate 2.7 Be able to create an original work of art using a variety of processes, materials, tools and media to express their ideas, thoughts, emotions and views of the world 2.8 Be able to create art to achieve a particular purpose so that the idea goes beyond art being exclusively for self-expression and creativity 2.9 Be able to evaluate their initial artistic products and adjust the work to better suit their expression 2.10 Be able to describe works of art in terms of meaning, design, materials, technique, place and time 2.11 Begin to develop an understanding of the benefits, limitations and consequences of visual communication media around the world such as film, the Internet, print, television and video 2.12 Begin to develop an understanding of how artists are influenced by their background and experience and that they in turn affect others through their work 3. GEOGRAPHY Students will: 32 3.1 Know that the study of geography is concerned with places and environments in the world 3.2 Know about the main physical and human features and environmental issues in particular localities 3.3 Know about the varying geographical patterns and physical processes of different places 3.4 Know about the geography, weather and climate of particular localities 3.5 Know about the similarities and differences between particular localities 3.6 Know how the features of particular localities influence the nature of human activities within them 3.7 Know about recent and proposed changes in particular localities 3.8 Know how people and their actions affect the environment and physical features of a place 3.9 Know the relationship between weather, climate and environmental features From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 3.10 Know how the weather and climate affect, and are affected by, human behaviour 3.11 Know how the geography of a region shapes economic development 3.12 Know how the combination of the geographical, environmental and economic features of a region impact human distribution patterns 3.13 Be able to use and interpret globes, maps, atlases, photographs, computer models and satellite images in a variety of scales 3.14 Be able to make plans and maps using a variety of scales, symbols and keys 3.15 Be able to describe geographic locations using standard measures 3.16 Be able to use appropriate geographical vocabulary to describe and interpret their surroundings as well as other countries and continents 3.17 Be able to explain how geographical features and phenomena impact economic interactions between countries and regions 3.18 Be able to explain the relationships between the physical characteristics and human behaviours that shape a region 3.19 Be able to use maps in a variety of scales to locate the position, geographical features and social environments of other countries and continents to gain an understanding of daily life 3.20 Be able to explain how physical and human processes lead to similarities and differences between places 3.21 Be able to explain how places and people are interdependently linked through the movement of goods and people 3.22 Develop an understanding of how localities are affected by natural features and processes 3.23 Develop an understanding of how and why people seek to manage and sustain their environment 4. HISTORY Students will: 4.1 Know the characteristic features of particular periods and societies 4.2 Know that the study of history is concerned with the past in relation to the present 4.3 Know the history of the periods being studied 4.4 Know about the ideas, beliefs, attitudes and experiences of people in the past 4.5 Know about the social, cultural, religious and ethnic diversity of the periods studied 4.6 Be able to use historical terms associated with the periods they have studied From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 33 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 4.7 Be able to enquire into historical questions and their effects on people’s lives 4.8 Be able to describe how the countries studied have responded to the conflicts, social changes, political changes and economic developments that represent their history 4.9 Be able to describe aspects of the past from a range of sources 4.10 Be able to describe and identify the causes for and the results of historical events, situations and changes in the periods they have studied 4.11 Be able to describe and make links between the main events, situations and changes both within and across periods 4.12 Be able to describe how the history of the countries studied affects the lives of the people who live there now 4.13 Be able to describe how the history of one country affects that of another 4.14 Be able to select and record information relevant to a historical topic 4.15 Be able to place the events, people and changes in the periods they have studied into a chronological framework 4.16 Be able to describe how certain aspects of the past have been represented and interpreted in different ways 4.17 Develop an understanding of how historical sources can be different from and contradict one another and that they reflect their context of time, place and viewpoint 4.18 Develop an understanding for how contradicting views of power, morality and religion lead to local and global cooperation and conflicts 5. GEOGRAPHY Students will: 34 5.1 Know that the study of geography is concerned with places and environments in the world 5.2 Know about the main physical and human features and environmental issues in particular localities 5.3 Know about the varying geographical patterns and physical processes of different places 5.4 Know about the geography, weather and climate of particular localities 5.5 Know about the similarities and differences between particular localities 5.6 Know how the features of particular localities influence the nature of human activities within them 5.7 Know about recent and proposed changes in particular localities From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 5.8 Know how people and their actions affect the environment and physical features of a place 5.9 Know the relationship between weather, climate and environmental features 5.10 Know how the weather and climate affect, and are affected by, human behaviour 5.11 Know how the geography of a region shapes economic development 5.12 Know how the combination of the geographical, environmental and economic features of a region impact human distribution patterns 5.13 Be able to use and interpret globes, maps, atlases, photographs, computer models and satellite images in a variety of scales 5.14 Be able to make plans and maps using a variety of scales, symbols and keys 5.15 Be able to describe geographic locations using standard measures 5.16 Be able to use appropriate geographical vocabulary to describe and interpret their surroundings as well as other countries and continents 5.17 Be able to explain how geographical features and phenomena impact economic interactions between countries and regions 5.18 Be able to explain the relationships between the physical characteristics and human behaviours that shape a region 5.19 Be able to use maps in a variety of scales to locate the position, geographical features and social environments of other countries and continents to gain an understanding of daily life 5.20 Be able to explain how physical and human processes lead to similarities and differences between places 5.21 Be able to explain how places and people are interdependently linked through the movement of goods and people 5.22 Develop an understanding of how localities are affected by natural features and processes 5.23 Develop an understanding of how and why people seek to manage and sustain their environment 6. ICT and Computing: Digital Literacy Students will: 6.1 Know that the study of ICT and Computing is concerned with designing and applying technology to gather, use and exchange information 6.2 Know about different ways to find and identify credible and respected digital resources, and how to cite digital sources in their work From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 35 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 6.3 Know how to protect their online identity, privacy and safety and avoid undesirable contact, content and other threats (such as malicious software) 6.4 Know about digital footprints and online reputations; including how to control, protect and develop a positive online identity 6.5 Be able to select and use technology and the internet safely, responsibly, respectfully, creatively and competently, for a range of purposes and audiences 6.6 Be able to manipulate, combine and present different forms of information from different sources in an organised and efficient way 6.7 Develop an understanding of the responsibilities and repercussions of online behaviour, including issues associated with netiquette, cyberbullying, privacy and ethical issues Digital Science Students will: 6.8 Be able to plan, develop, test and refine programs which include functions and procedures, in order to solve a range of computational problem 6.9 Be able to solve a range of problems by applying different algorithms and identifying the most effective according to purpose and outcome 6.10 Be able to interpret and apply Boolean logic; using and applying operators in searches, circuits and programs 6.11 Be able to make a simple computer or a model of one, explaining how data is stored and programs are executed 6.12 Develop an understanding of how many different types of data can be stored digitally, in the form of binary digits; and be able to perform calculations using the binary system 6.13 Develop an understanding of how the internet, the World Wide Web and Cloud computing function, and how they facilitate communication and creativity Digital Tools Students will: 6.14 Know how to produce and edit text, image, audio, and video. Recognise an increasing range of different file types, and how these can be converted for different purposes. 6.15 Be able to communicate effectively using a range of digital tools including online environments 6.16 Be able to evaluate digital tools analytically, identifying and using appropriate hardware and software to solve a variety of problems 6.17 Be able to use ICT to plan and control events, including using digital technologies to sense a range of physical data and program physical events 36 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 6.18 Be able to gather and interrogate information by framing questions appropriately 6.19 Be able to interpret their findings and identify whether their findings are valid 6.20 Develop an understanding that the quality of information affects the results of any enquiry 6.21 Develop an understanding of how digital tools can be applied analytically to solve problems by designing, creating and using computer models, e.g. 3D design using computer assisted design software, gaming software and spreadsheets to create simulations Digital Design Students will: 6.22 Know how to apply design principles when developing computer models and programs 6.23 Be able to design, write and debug computer programs in two or more programming languages (e.g. Python, Ruby, PHP, HTML) 6.24 Be able to design, create, use and evaluate creative digital solutions for authentic purposes, considering the end-user 6.25 Develop an understanding of the user-centered design process and apply this in practice when creating digital content 7. LANGUAGE ARTS Students will: Speaking and Listening 7.1 Be able to play a variety of roles in group discussions by reading required material and being prepared 7.2 Be able to ask and answer questions to obtain clarification and elaboration with relevant evidence 7.3 Be able to integrate strategies and tools such as multimedia to enhance listening comprehension and add interest 7.4 Be able to use the content, intention and perspective of what is said to them in a variety of situations 7.5 Be able to convey information, experiences, arguments and opinions clearly and confidently when speaking to others 7.6 Be able to use appropriate vocabulary in speech 7.7 Be able to analyse the purpose and motivation of the information presented 7.8 Be able to use spoken language that is appropriate to the situation and purpose From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 37 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Reading 7.9 Be able to read and comprehend for different purposes including stories, dramas, poems and literature 7.10 Be able to use a variety of strategies to understand meaning 7.11 Be able to determine the theme of a text and its relationship to plot, setting and characters 7.12 Be able to cite evidence that supports explicit and inferred meaning from the text 7.13 Be able to distinguish between fact and fiction 7.14 Be able to compare and contrast information from a variety of texts to understand how it affects meaning and style 7.15 Be able to read for pleasure and enjoyment 7.16 Develop an understanding for how meaning is constructed using word choice, tone and timing Writing 7.17 Be able to write in a range of different forms appropriate for their purpose and readers 7.18 Be able to write narratives to communicate real or imagined events using descriptive details and event sequences 7.19 Be able to write arguments to support claims using evidence from texts and research from credible sources 7.20 Be able to write informative or explanatory texts to examine a topic and share ideas in an organised manner 7.21 Be able to use writing to organise thoughts, experiences, emotions and preferences 7.22 Be able to write short reports to answer a question 7.23 Be able to use a range of strategies and tools for planning, drafting and revising their writing 7.24 Be able to write neatly and legibly Language Awareness 7.25 Know the rules for grammatical construction and usage 7.26 Know the rules for spelling, punctuation and capitalisation 7.27 Be able to recognise the devices used by an author to accomplish a purpose 7.28 Be able to recognise different forms, genres and themes 38 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 7.29 Be able to explain and describe the main features, ideas, themes, events, information and characters in a text 7.30 Be able to recognise and use figures of speech 7.31 Be able to recognise and use descriptive language 7.32 Be able to recognise and use literal language 7.33 Be able to recognise and use different forms, styles and genres 7.34 Be able to recognise and use different linguistic conventions 7.35 Develop an understanding that language is used differently in different situations 7.36 Develop an understanding that language and the way it is used affects the relationships between people 7.37 Develop an understanding that there are cultural differences between the way language is used by different people and in different situations 7.38 Develop an understanding that the meaning of language can be influenced by the situation, form, unexpressed intentions, physical posture, facial expression and gestures 7.39 Develop an understanding that forms of communication benefit from the application of rules Drama 7.40 Know that everyone has a creative side 7.41 Be able to improvise a play, using the roles, situation and elements of a story 7.42 Be able to perform a scripted play 7.43 Be able to make use of voice, language, posture, movement and facial expression 7.44 Be able to make use of scenery, stage properties, costume and make-up 7.45 Be able to evaluate their own performance and that of others 7.46 Be able to respond to a performance identifying the key elements and Devices 8. MATHEMATICS Students will: Using Mathematics 8.1 Know examples of how mathematics is used in everyday life and by whom 8.2 Be able to apply mathematics in real life situations From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 39 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Numbers and Algebra 8.3 Be able to solve problems using fractions, decimals and percentages 8.4 Be able to represent quantitative relationships using ratios and proportions 8.5 Be able to use exponential, scientific and calculator notation 8.6 Be able to solve problems using prime numbers, factors, prime factorisation and multiples 8.7 Be able to simplify computations involving integers, fractions and decimals using the associative and commutative properties of addition and multiplication 8.8 Be able to use tables, graphs, words and symbolic representations to represent and analyse general patterns of data, particularly linear relationships 8.9 Be able to identify and differentiate linear and non-linear functions from equations, tables and graphs 8.10 Be able to solve problems using algebraic representation Measurement and Geometry 8.11 Know how to describe and classify two- and three-dimensional objects 8.12 Know formulas that represent geometric shapes 8.13 Be able to present deductive arguments using congruence, similarity and Pythagoras’ theorem 8.14 Be able to represent geometric shapes using coordinate geometry 8.15 Be able to use transformations to move, reorientate and adjust the size of geometric objects 8.16 Be able to use formulas that represent geometric shapes 8.17 Be able to determine the area of complex shapes 8.18 Develop an understanding of the relationships between angles, length of sides, perimeter, area and volume for similar objects 8.19 Develop an understanding of the relationships between two- and threedimensional objects Statistics 8.20 Know the measures of centre and spread for statistical data 8.21 Be able to develop a study to collect data in relation to two characteristics 8.22 Be able to select and create an appropriate graphical representation of data to suit a particular situation and audience 8.23 Be able to interpret statistical data, including graphic representation 8.24 Be able to interpret a situation using proportionality or probability 40 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 9. MUSIC Students will: 9.1 Know that the study of music is concerned with musical expression and communication 9.2 Know the uses of the elements of music 9.3 Know about the origins and history of musical styles and instruments 9.4 Know the characteristics of representative music genres and styles from a variety of cultures 9.5 Know the functions music serves, the roles of musicians and the conditions under which music is typically performed in several cultures 9.6 Be able to use music vocabulary and apply the elements of music to analyse and describe musical forms 9.7 Be able to interpret standard notation symbols 9.8 Be able to sing and/or play a melody with accompaniment 9.9 Be able to make links between music and other disciplines taught in school 9.10 Be able to create or compose short pieces within specified parameters 9.11 Be able to perform a repertoire of music, alone or with others, paying attention to performance practice, breath control, posture and tone quality 9.12 Be able to make judgments about pieces of music, showing understanding, appreciation, respect and enjoyment as appropriate 9.13 Be able to display a range of emotions whilst playing instruments and singing 9.14 Be able to improvise, extend or create music to express emotion, ideas, creativity and imagination 9.15 Be able to perform as part of an ensemble and contribute to the overall experience of the collaboration 9.16 Be able to consider pieces of music in terms of meaning, mood, structure, place and time 9.17 Understand that the work of musicians is influenced by their environment and experiences 10. PHYSICAL EDUCATION Students will: 10.1 Know that the study of physical education is concerned with healthy lifestyle choices and activity which lead to physical, emotional and mental balance 10.2 Know the principal rules of established sporting and athletic activities From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 41 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 10.3 Know the principles of water safety 10.4 Know how to avoid and reduce injuries 10.5 Know how to respond to challenges and disappointments with confidence and appropriate emotions during athletic events 10.6 Be able to steadily improve performance with control, coordination, precision and consistency in a range of physical skills and techniques whenever possible 10.7 Be able to select a physical activity they enjoy and decide how they will participate in their chosen activity 10.8 Be able to make healthy choices with regard to food and diet 10.9 Be able to participate in regulation team games as well as individual competitions 10.10 Be able to use safe and acceptable tactics to steadily improve their own performance and that of a team 10.11 Be able to identify the features of a good physical performance 10.12 Be able to evaluate their own performance objectively and make a plan of action 10.13 Be able to apply the rules and conventions of a range of sports and activities 10.14 Be able to use physical movement as a means of expression, enjoyment, communication and art 10.15 Be able to swim a distance of at least 100 metres whenever possible 10.16 Develop an understanding of how physical activity affects the body, the mind and emotions 10.17 Develop an understanding of the importance of diet and personal hygiene 10.18 Develop an understanding of the importance of safety procedures and lifesaving techniques 10.19 Develop an understanding of how attitudes towards health and behaviour differ based on cultural values and beliefs 11. Science Learning Goals Scientific Enquiry Students will: 11.1 Know that the study of science is concerned with investigating and understanding the animate and inanimate world around them 11.2 Be able to conduct scientific investigations with rigour by being able to: a) 42 Select a scientific issue to investigate and formulate a research question that recognises a potential relationship between two variables, and generate a hypothesis From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E b) Plan an investigation and make predictions c) Select appropriate apparatus and sampling groups, and identify health and safety issues d) Make systematic and accurate measurements to gather data to test a hypothesis e) Record and present his/her findings accurately using the most appropriate medium, scientific vocabulary and conventions f) Identify patterns in the results and draw conclusions based on the evidence g) Suggest ways in which his/her investigations and working methods could be improved h) Relate their own investigations to wider scientific ideas 11.3 Be able to discriminate between evidence and opinion 11.4 Develop an understanding that scientific knowledge is built up from the systematic collection and analysis of evidence and the application of rigorous reasoning applied to the evidence 11.5 Develop an understanding that scientific evidence is subject to multiple interpretations 11.6 Develop an understanding of the importance of using objective evidence to test scientific ideas 11.7 Develop an understanding of the ethical responsibility all scientists face The Science of Living Things (Biology) Students will: 11.8 Know about the fundamental units/building blocks of life and that all living organisms are configured around structures; hierarchical organisation from cells to tissues to organs to systems to organisms 11.9 Know the structure and functions of a cell, tissue, organs and organ systems in humans and animals 11.10 Know about the structure and functions of complex systems in humans and other animals; including the skeletal and muscular systems, nutrition and digestion, gas exchange systems and reproduction 11.11 Know about the structure and functions of complex systems in plants; including photosynthesis in the leaves, the role of leaf stomata in gas exchange and reproduction in plants, including pollination and fertilisation 11.12 Know about the seven characteristics which define living things 11.13 Know about taxonomy: the classification of living things From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 43 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 11.14 Know about the interdependence of organisms in an ecosystem, including how living things benefit and suffer due to internal and external influences in their environments 11.15 Know about the energy flow in a food chain, ecological pyramid and food web and the main processes at work, e.g. Photosynthesis and cellular respiration 11.16 Know about the key elements of inheritance, genetics and the theory of evolution 11.17 Be able to observe, identify and record plant and animal cell structure using a light microscope 11.18 Be able to classify animals and plants into major groups using some local examples 11.19 Be able to explain the consequences of imbalances in the diet, including obesity, starvation and deficiency diseases 11.20 Be able to describe and illustrate the mechanisms of the major internal systems of the human body 11.21 Be able to draw diagrams to illustrate simple food chains in an ecosystem 11.22 Be able to describe and illustrate the process of energy flow in a food chain, ecological pyramid or food web, including photosynthesis and respiration 11.23 Be able to explain the effects of drugs (including substance misuse) on behaviour, health and life processes 11.24 Develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between living things and the environment in which they live 11.25 Develop an understanding of the dependence of almost all life on the ability of photosynthetic organisms (like plants and algae) to store energy and maintain levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere 11.26 Develop an understanding of how tissues and organs function in order to create systems which maintain living organisms The Science of Chemistry Students will: 11.27 Know about the particulate nature, structure and properties of matter; atoms and molecules 11.28 Know about the structure and conservation of matter – materials and mass – and the total energy of a system 11.29 Know about energy transfer in chemical reactions (endothermic and exothermic reactions) 11.30 Know about the differences between elements, compounds, pure and impure substances and the separation of simple mixtures 44 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 11.31 Know about the formation of chemical bonds (covalent, ionic, and metallic) between atoms to form molecules and other compounds 11.32 Know about chemical reactions as the rearrangement or regrouping of atoms and the conservation of elements 11.33 Know about the chemical properties of common substances 11.34 Know about acids, bases and alkalis, their properties and chemical reactions 11.35 Know about the history, structure and uses of the Periodic Table of Elements 11.36 Be able to describe and illustrate an atom and its parts (nucleus, protons and electrons) using a simple model, e.g. the Dalton model 11.37 Be able to explain the physical arrangements of particles in solids, liquids and gases and the mechanism of changes of state 11.38 Be able to distinguish between elements, compounds and mixtures 11.39 Be able to use simple techniques for separating mixtures: filtration, evaporation, distillation and chromatography (where available) 11.40 Be able to represent simple chemical reactions using formulae and equations 11.41 Be able to classify materials according to their physical and chemical properties 11.42 Be able to use the Periodic Table to identify elements, know their symbols and classify them 11.43 Be able to predict trends in chemical reactions of elements in periods and groups 11.44 Be able to describe and predict the reactivity of metals with oxygen, water and dilute acids 11.45 Be able to define acids and alkalis in terms of neutralisation reactions – using indicators and the pH scale 11.46 Develop an understanding of how substances combine, change or react to form new substances 11.47 Develop an understanding and appreciation of scientific models/laws that explain the fundamental nature of things and the need to remain willing to re-examine existing models The Science of Physics Students will: 11.48 Know about the major types and sources of energy and how they are used and measured 11.49 Know that energy can be stored or transferred, but not created or destroyed 11.50 Know about the nature and effect of different types of forces, including balanced and unbalanced forces From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 45 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 11.51 Know about the effects of forces on motion and Newton’s laws of motion 11.52 Know that every object exerts a gravitational force on every other object 11.53 Know that pressure is caused by a force acting on an area 11.54 Know about pressure in fluids (gases and liquids) 11.55 Know about waves as energy transfer in matter and the properties of different types of waves, e.g. sound waves 11.56 Know about the properties of sound waves and the relationship between pitch, amplitude and frequency 11.57 Know about the properties of electromagnetic waves and the relationship between colour, frequency and wave length for light waves 11.58 Know about the similarities and differences between waves in matter (sound waves) and electromagnetic waves (light waves) 11.59 Know about magnetism and that magnetic forces either attract or repulse one another 11.60 Know about different types of electricity and current; e.g. current electricity, static electricity, direct and alternating current 11.61 Know about the magnetic effects of current and uses of electromagnetism, e.g. electromagnets and electric motors 11.62 Be able to define mass, weight, speed, velocity and acceleration and explain differences between them 11.63 Be able to calculate average speed using time and distance measurements 11.64 Be able to represent and interpret a journey on distance-time graphs 11.65 Be able to measure different types of forces 11.66 Be able to use diagrams to illustrate the strength and direction of forces and resultant forces in one dimension 11.67 Be able to use the ray model of light to explain imaging in mirrors, the reflection and refraction of light and the action of the convex lens in focusing light waves, e.g. the human eye 11.68 Be able to explore how electricity is produced and measured using various sources of energy 11.69 Be able to draw and interpret illustrative diagrams representing simple series and parallel direct current circuits 11.70 Be able to make measurements in simple series and parallel direct current circuits (electric current, potential difference, resistance) 11.71 Be able to draw and interpret illustrative diagrams representing magnetic fields by plotting field lines and showing magnetic poles 46 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 11.72 Be able to construct and use a simple Electromagnet 11.73 Develop an understanding of energy, its sources, uses and manifestations in multiple phenomena 11.74 Develop an understanding of the conservation and transfer of energy in a system 11.75 Develop an understanding of the relationships between time, distance, velocity and acceleration 11.76 Develop an understanding of the effects of forces on objects and that they can be used to predict stability or instability in systems The Science of the Earth and Solar System (Space physics) Students will: 11.77 Know about the main features and characteristics of the universe, including the relationship between Earth and the rest of the solar system 11.78 Know about the varying effects caused by Earth movements in different hemispheres. (E.g. The seasons and the Earth’s tilt and day length at different times of year) 11.79 4.79 Know about the effect of the force of gravity on the Earth, between the Earth and the Moon and the Earth and the Sun including the effect of gravity on the tides and on satellites around the Earth 11.80 Be able to explain the effect of gravity on objects on the Earth and objects that orbit the Earth, e.g. satellites 11.81 Develop an understanding of the effect of gravity on objects on the Earth, on satellites orbiting the Earth (weightlessness), and between the Earth and the Sun and the rest of the solar system 12. TECHNOLOGY Students will: 12.1 Know that technology is concerned with designing and making systems that aid the needs of a society 12.2 Know how the lives of people in different countries are affected by the extent of technological advance 12.3 Know how to combine creativity with skills to predict new ideas and inventions 12.4 Know that the natural resources available in a particular region affect the development and progress of its technology 12.5 Know that the quality of a product depends on how well it is made and how well it meets its intended purpose 12.6 Know about the principles of nutrition and health and the properties and characteristics of the different food groups From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 47 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 12.7 Be able to investigate the way in which simple products in everyday use are designed and made and how they work 12.8 Be able to identify and respond to needs, wants and opportunities with informed designs and products 12.9 Be able to plan and organise a sequence of activities to produce an effective system or product 12.10 Be able to work with a variety of tools and materials confidently and safely to create goods and products 12.11 Be able to test and evaluate the construction of their own work and improve on it 12.12 Be able to evaluate the effectiveness of simple products in everyday use 12.13 Be able to plan for a healthy and nutritious dish by using the properties, seasonality and characteristics of a broad range of ingredients 12.14 Be able to use a broad range of cooking techniques competently 12.15 Be able to cook a repertoire of savoury dishes to feed themselves and others a healthy nutritious and varied diet 12.16 Develop an understanding of developments in design and technology and how technology can impact individuals, society and the environment. 12.17 Develop an understanding of the principles of nutrition and health how basic ingredients can be used to cook healthy, nutritious meals. Part 2: The International Learning Goals 1. INTERNATIONAL MINDEDNESS Students will: 48 1.1 Know about the key features related to the different lives of people in their home country and, where appropriate, their parents’ home countries 1.2 Know about the key features related to the different lives of people in the countries they have studied 1.3 Know about ways in which the lives of people in the countries they have studied affect each other 1.4 Know about the similarities and the differences between the lives of people in different countries 1.5 Be able to explain how the lives of people in one country or group are affected by the activities of other countries or groups 1.6 Be able to identify ways in which people work together for mutual benefit 1.7 Be able to develop an increasingly mature response to the ‘other’ From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 1.8 Be able to appreciate another country, culture, society whilst still valuing and taking pride in one’s own 1.9 Be able to show consideration for others when making choices and decisions both in and outside of the school community 1.10 Be better able to recognise the nature of friendship, how to make and keep friends and display effective social relationships 1.11 Develop an understanding that there is value in knowing and understanding both the similarities and the differences between different countries 1.12 Develop an understanding of the impact of culture, law and economics on host countries when groups migrate Part 3: Personal Goals Students will: Enquiry The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.1 Be able to ask and consider searching questions related to the area of study 1.2 Be able to plan and carry out investigations related to these questions 1.3 Be able to collect reliable evidence from their investigations 1.4 Be able to use the evidence to draw sustainable conclusions 1.5 Be able to relate the conclusions to wider issues Adaptability The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.6 Know about a range of views, cultures and traditions 1.7 Be able to consider and respect the views, cultures and traditions of other people 1.8 Be able to cope with unfamiliar situations 1.9 Be able to approach tasks with confidence 1.10 Be able to suggest and explore new roles, ideas and strategies 1.11 Be able to move between conventional and more fluid forms of thinking 1.12 Be able to be at ease with themselves in a variety of situations 1.13 Be better able to recognise physical and emotional changes that occur at puberty and manage these in a positive way 1.14 Be better able to deal with their own and other’s feelings From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 49 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Resilience The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.15 Be able to stick with a task until it is completed 1.16 Be able to cope with the disappointment they face when they are not successful in their activities 1.17 Be able to try again when they are not successful in their activities 1.18 Be better able to recognise the stages of emotion associated with loss and change Morality The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.19 Know about the moral issues associated with the subjects they study 1.20 Know about and respect alternative moral standpoints 1.21 Be able to develop their own moral standpoints 1.22 Be able to act on their own moral standpoints 1.23 Be able to explain the reasons for their actions 1.24 Be better able to recognise their value as individuals Communication The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.25 Be able to make their meaning plain using appropriate verbal and non-verbal forms 1.26 Be able to use a variety of tools and technologies to aid their communication 1.27 Be able to communicate in more than one spoken language 1.28 Be able to communicate in a range of different contexts and with a range of different audiences 1.29 Be better able to communicate effectively and appropriately with individuals, and reflect upon how their actions affect themselves and others Thoughtfulness The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.30 Be able to identify and consider issues raised in their studies 1.31 Be able to use a range of thinking skills in solving problems 1.32 Be able to consider and respect alternative points of view 1.33 Be able to draw conclusions and develop their own reasoning 50 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 1.34 Be able to reflect on what they have learned and its implications for their own lives and the lives of other people 1.35 Be able to identify their own strengths and weaknesses 1.36 Be able to identify and act on ways of developing their strengths and overcoming their weaknesses 1.37 Be better able to make decisions and apply possible solutions to a variety of problems that young people encounter Cooperation The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.38 Understand that different people have different roles to play in groups 1.39 Be able to adopt different roles depending on the needs of the group and on the activity 1.40 Be able to work alongside and in cooperation with others to undertake activities and achieve targets Respect The vast majority of students will, through their study of the IMYC: 1.41 Know about the value and importance of respecting themselves and their bodies 1.42 Know about the varying needs of other people, other living things and the environment 1.43 Be able to show respect for the needs of other people, other living things and the environment 1.44 Be able to act in accordance with the needs of other people, other living things and the environment From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 51 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Appendix B: Research into Learning The recent explosion of research from neuroscience and cognitive science has been of great interest to teachers and leaders. Some of it can be of real, practical help to educators that want to improve learning. It provides new ideas to use in the classroom and helps to explain why some of our intuitive, but previously difficult to justify, methods work as well as they do. But there is also a danger of jumping on the bandwagon too soon. Too many writers and educationalists have been quick to advocate teaching methods and techniques that are simply not supported by any reliable evidence – you may have seen some of these referred to in the media as ‘neuromyths’. Although we have learnt so much in recent years there is still much more that is not yet understood, even by brain researchers, most of whom are loathe to recommend many popular approaches to teachers at all. For this reason we encourage school leaders and teachers to view research into learning as a non-negotiable part of their own learning and professional development. Through reading, research and sharing, teachers should develop deep insights into the nature of learning and not only apply this in their classrooms, but share this learning with their children. We can’t cover the breadth of research that’s out there, but here are some interesting trends and themes you might want to consider: 1. Growth Mindsets The concept of ‘fixed’ and ‘growth’ mindsets stems from the research carried out by Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck. One of her best known studies involved splitting children into two groups and giving them an identical test, at which most would succeed. One group were told they had done really well because they tried really hard. The other group were told they had done really well because they were smart. They were then told they were going to have another test, but could choose from a simple one or a harder one from which they might learn more. The group who were praised for their effort nearly all wanted to try the harder test. In the group that were praised for their intelligence, nearly 80% opted for the easier test. Dweck’s research highlights the difference between what she calls a ‘fixed’ mindset (performance orientated, likely to give up easily and not fulfil their potential) versus a ‘growth’ mindset (learning orientated, believes intelligence can be developed and embraces challenges). The message is clear – praise process and not ability. In an article ‘You Can Grow Your Intelligence’ (2008) Dweck talks about the brain being more like a muscle which changes and gets stronger the more you use it – something which is underpinned by scientific research. She explains how neurons in the brain are connected to other cells in the network and it is the communication between these brain cells which 52 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E allows people to think and solve problems. Neurons are hard-wired to make connections with each other and when we learn things these connections multiply and get stronger. As you learn, your brain is looking for connections between your current and previous learning. This is why the ‘Big Idea’ and knowledge harvest is such an important part of any IMYC unit – it helps children make connections between what they already know and what they are going to learn. 2. Meta-cognition Meta-cognition is the term used to describe learning about learning, or what learning consists of (Outstanding Formative Assessment, Shirley Clarke, 2014). It is worth referencing here the work of Professor John Hattie, an educational researcher who developed a way of ranking various influences on learning through a range of meta-analyses. He synthesised more than 900 meta-analyses, involving over 50,000 studies and drawing on the experiences of 240 million school-aged students. His book, Visible Learning (2009), identified 150 classroom interventions and listed them in order of effectiveness. Meta-cognitive strategies ranked at number 13 in the list. In his book Hattie explains, “when tasks are more complex for a pupil, the quality of meta-cognitive skills rather than intellectual ability is the main determinant of learning outcomes.” Thinking about learning is important. In the book Making Thinking Visible (Ritchhart, Church and Morrison, 2011) colleagues from Harvard’s Project Zero have developed a set of thinking routines that not only help children to learn, but also to learn how to learn. The authors explain that ‘it’s one thing for us as teachers to articulate the kinds of thinking we are seeking to promote; it is another for students to develop a greater awareness of the significant role that thinking plays in cultivating their own understanding.’ ‘Slow thinking’ (a term used by Gay Claxton in his book Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind, 1998) is also something that teachers need to consider when the children are reflecting on their learning. When faced with difficult and complex learning, our brains need a large amount of input followed by a period of downtime. During this downtime, our brains continue to process the information we have received. This process of digestion and sedimentation has come to be known as ‘slow thinking’. This is why it’s a good idea to have the knowledge harvest and explaining the theme on display throughout a unit, so children can always be slow thinking their ideas and questions, and piecing the answers together over time. Throughout the IMYC units you will find many opportunities to help teachers and students think about learning (Reflective journaling) and learn more about how we learn. 3. Memory Daniel T. Willingham, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Virginia, explores the process of memory in his book Why Don’t Students Like School? (2009). He believes that the mind is not designed for thinking, and when it can get away with it, our brains will rely on memory instead. Broadly speaking, we have two types of memory – the working memory (or short term memory) and the long term memory. Space in our working memory is limited – it From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 53 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E is only able to hold around 3-7 new pieces of information at any one time – and too often we overload it. Successful learning involves transferring information and knowledge from our working memory into our long term memory and being able to retrieve them again. This can be achieved through the use of memory aids such as ‘chunking’, and through a balance of introducing new learning and consolidating existing learning. Daisy Christodoulou adds to Willingham’s argument in her book Seven Myths About Education (2014). In it she explains that our long term memory is capable of storing thousands of facts, and these facts combined form what is known as a ‘schema’. When we meet new facts about a topic or area of learning, we assimilate them into that schema meaning that if we already have a lot of facts in that particular schema, it is much easier for us to learn new things about a topic. Willingham also asserts this when he says that, ‘those who know more knowledge, gain more knowledge’ (2009). This has interesting implications for embarking on the IMYC units of work – do your students have the necessary background knowledge to access the learning tasks you are going to set them? In light of this teachers may consider carrying out the knowledge harvest before the entry point, or sending home some key information about a topic before children start their learning. And it’s not just only knowledge we need to work on, it’s also skills. Willingham believes children should still practice something even when it appears they have mastered the skill and are no longer improving. He tells us that, ‘Mental processes can become automised’ (2009) and it is this mastery which reinforces the basic skills that are required for the learning of more advanced skills, and this practice that protects against forgetting, improves transfer and clears the working memory for thinking. 4. Positive and negative emotions Negative emotions inhibit learning from taking place. Positive emotions can help learning take place. All strong emotions leave memory traces. There are important implications for classroom practices here. Firstly, deep engagement in learning activities is linked to having positive experiences. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Professor of Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University, is the architect of the notion of ‘flow’ as being one of the components of great fun (Flow: The Psychology of Happiness, 2002). ‘Great fun’ in this context is something that results from rigorous engagement in an activity as much as it results from a quick hit of immediate gratification. When planning for learning activities, a rigorous approach supported by a range of appropriate strategies and interventions is essential. Secondly, Willingham tells us that our memory is a product of what we think about. What we want children to think about is learning. So when planning a lively enjoyable lesson, it is important to ensure that the learning is still made clear, and is shared, revisited and reflected on. Remember to always ask yourself ‘what are the children learning?’ rather than being concerned with what the children are doing. Thirdly, just as most of us will have experienced a state of ‘flow’ at some time or another, so we will have experienced the crippling effect of stress on our ability to learn. In his book 54 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Emotional Intelligence (1996), Daniel Goleman shows clearly why stress is such an important inhibitor to learning, as it can result in what he calls emotional ‘flooding’ or ‘hi-jacking’ in parts of the brain. The best state for learning is ‘relaxed alertness’. Children who are stressed can’t learn; it’s as simple as that. Because of this, it is vital that educators acknowledge the importance of creating a positive environment for learning. 5. Assessment for learning ‘The most powerful educational tool for raising achievement and preparing children to be lifelong learners, in any context, is formative assessment.’ Shirley Clarke Outstanding Formative Assessment, (2014) Clarke’s statement is bolstered by the outcomes of Hattie’s research which ranks key aspects of formative assessment at the top end of the list including: ■■ Assessment literate students (students who know what they are learning, have success criteria, can self-assess, etc.) ■■ Providing formative evaluation ■■ Feedback There’s no getting around it – if we’re passionate about improving children’s learning, we need to be passionate about assessment too. 6. Understanding is tricky Understanding has been poorly represented in many curricula, with an additional pressure to use the term inappropriately. In an educational sense, understanding has come to have great power and is frequently cited as the goal of most learning. Because of this, sometimes curriculum writers and developers have focused on developing and assessing understanding without realising how complex it is. Educators have been grappling with their ‘understanding’ of understanding for many years. In 1933, in his book How We Think, John Dewey described understanding as ‘the result of facts acquiring meaning for the learner. To grasp the meaning of the thing, an event, or a situation is to see it in its relationship to other things: to see how it operates or functions, what consequences follow from it, what causes it, what uses it can be put to (…)The relation of means-consequence is the center and heart of all understanding’. Willingham (2009) has his own ideas about understanding. To him, understanding is in factremembering in disguise, and pupils understand new things (things they don’t know) by relating them to old ideas (things they do know). He explains that understanding the new ideas is mostly about getting the right old ideas into the working memory and rearranging them, making comparisons and thinking about them in a different way. Willingham also talks of the need to be realistic about what students can achieve and how quickly this can be done. Teaching and assessing for understanding all the time is therefore misguided. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 55 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E 7. The link between mind and body There is a lot of recent and emerging researching into the link between mind and body, and what we are consistently being told is that good diet, general health, exercise and a good night’s sleep can help our brains work more effectively. For general brain and body health, a balanced diet including plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables is vital. Your brain also needs a steady supply of energy, which it can get from glucose (which can be found in certain types of carbohydrates). Exercise is also believed to be another important ingredient for a healthy brain. Not only does exercise ensure the brain gets plenty of oxygen, research also suggests that it can support learning and memory too. David Bucci, an associate professor at Dartmouth’s Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, explains that ‘The implication is that exercising during development, as your brain is growing, is changing the brain in concert with normal developmental changes, resulting in your having more permanent wiring of the brain in support of things like learning and memory. It seems important to (exercise) early in life.’ (Exercise Affects the Brain, Petra Rattue, 2012, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/245751.php). Getting enough sleep is equally important as it allows the brain to repair itself and consolidate all of the learning that has taken place that day. In addition to this, studies by an American research team show sleep to be important as it is during this time that brain cells shrink and open up gaps between neurons allowing fluid to wash the brain clean (Sleep ‘cleans’ the brain of toxins, James Gallagher, 2013, www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-24567412). 56 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E References Books Seven Myths About Education, Daisy Christodoulou, Routledge, 2014 Outstanding Formative Assessment, Shirley Clarke, Hodder Education, 2014 Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind, Guy Claxton, Fourth Estate, 1998 Flow: The Psychology of Happiness: The Classic Work on How to Achieve Happiness, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Rider, 2002 How We Think, John Dewey, Martino Fine Books, 2011 Mindset: How You Can Fulfil Your Potential, Carol Dweck, Robinson, 2012 Emotional Intelligence – Why It Matters More Than IQ, Daniel J. Goleman, Bloomsbury, 1996 Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, John Hattie, Routledge, 2008 Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners, Ritchart, Church and Morrison, Jossey Bass, 2011 Why Don’t Students Like School? Daniel T. Willingham, Jossey Bass, 2009 Articles You Can Grow Your Intelligence, Carol Dweck, 2009. (Available to download from www.mindsetworks.com/free-resources) Sleep ‘cleans’ the brain of toxins, James Gallagher, 2013. (Available to download from www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-24567412) Informing Pedagogy Through Brain-Targeted Teaching, Mariale Hardiman, 2012. (Available to download from http://jmbe.asm.org/index.php/jmbe/article/view/354/html) Exercise Affects the Brain, Petra Rattue, 2012. (Available to download from www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/245751.php) From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 57 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Appendix C: Five Key Needs of the Adolescent Brain 58 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E The International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC) is specifically designed to support the needs of the developing adolescent brain in ways which will improve the learning of 11–14 year olds. The IMYC believes that adolescents have particular needs, and an effective curriculum is designed to support and improve their learning through this critical time, it is in fact the IMYC’s own ‘Big Idea’. The IMYC has carried out extensive studies into current neuroscientific research into how the adolescent brain learns, and this appendix describes the key needs of the adolescent brain identified through the relevant research. The appendix includes a resources section that is by no means exhaustive but seeks to share the main studies that were used to come to the conclusions that we have. An excellent video (featuring Sarah-Jayne Blackmore) which summarises this research can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zVS8HIPUng Key need 1: Interlinking learning In recent years neuroscientific research has informed us that the brain learns by making connections between brain cells (neurons); thus forming a constellation of neurons related to a particular concept or idea, sometimes referred to by neuroscientists and psychologists as a ‘chunk’ of information. ‘Chunk’ is a term referring to the process of taking individual units of information (chunks) and grouping them into larger units. Probably the most common example of chunking occurs in phone numbers. For example, a phone number sequence of 4-7-1-1-3-2-4 would be chunked into 471-1324. Chunking is often a useful tool when memorising large amounts of information. By separating disparate individual elements into larger blocks, information becomes easier to retain and recall (The Dictionary of Psychology). Eric Kandel was the first scientist to figure out the cellular basis of this process and was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2000 for his work. He demonstrated that when people learn something, the wiring in their brain literally changes (neuroscientists say the brain retains its ‘plasticity’ and therefore the ability to learn, for most of our lives). We now know that neurons can make new connections, break a connection on one spot and make a new connection with another neuron nearby. (In Fieldwork Education’s Looking for Learning Toolkit we call this ‘New Learning1). The moment we learn something new, the information is literally ‘sliced’ into different ‘bits’ and stored in different parts of the brain (This process is known as ‘encoding’). The key to remembering (retrieving) our learning is to ‘reunite’ this information successfully to make sense of it, i.e. finding the concept or idea used in the encoding; in the same way an algorithm in mathematics brings different things together in a specific way. In his book Pieces of Light: The new science of memory, (2012) Daniel Schacter states: ‘We now know that we do not record our experiences the way a camera records them. Our memories work differently. We extract key elements from our experiences and store them. We then recreate our experiences rather than retrieve copies of them.’ 1 The Looking for Learning Toolkit: The WCLS group 2008. Schools have informed us that the Looking for Learning Toolkit has been helpful for improving learning in their schools From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 59 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Neuroscientific research often uses people that have suffered strokes to particular parts of the brain to study the different regions and their functions. For example, John Medina, in his book Brain Rules (2008) tells the story of a woman that suffered a stroke and lost her ability to use written vowels. She would write a simple sentence like ‘The dog chased the cat’ as: ‘Th_ d_g ch_s_d th_ c_t’ which is an example of how we know that vowels and consonants are not stored in the same place in the brain. If a connection between chunks of information is strengthened, the neurons strengthen their connections with each other, increasing the efficiency of the link (in the Looking for Learning Toolkit we call this ‘Consolidating Learning’). Dr Dean Buonomano (professor in the departments of Neurobiology and Psychology and the Brain Research Institute of UCLA) in his book Brain Bugs (2012) explains: ‘Learning new associations (new links between nodes) could correspond to the strengthening of weak synapses or forming of new ones. Synapses are the interface between neurons’ This effectively means that the brain looks for ‘previous’ learning when confronted with new experiences or information, and tries to link the new information with any previous information it has encoded. Neuroscientists say the brain learns ‘associatively’, always looking for patterns and linking to previous learning. In primary schools teachers often find these links for students and regularly mention links between discreet subjects’ learning. For example in the IPC Self-Review, Criterion 8, we refer to ‘Independent yet Interdependent Subjects’. The organisation of secondary school teaching and learning is often within departments, resulting in students suddenly having the responsibility of finding their own links in their learning. The aim of the IMYC is to help students develop the habit of identifying links in their learning for themselves through linking all learning within a concept called the Big Idea. This helps students to develop multiple perspectives. The IMYC links the knowledge, skills and understanding of each subject to the most appropriate Big Idea. This helps students to find the link or concept that their brain had used to encode learning, making retrieval easier. This requires all teachers to support the students in finding links to the Big Idea even if the subject does not have specific tasks in the IMYC resources. 60 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E SCIENCE MUSIC MATHS ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE HISTORY ART When people work together they can achieve a common goal GEOGRAPHY ENGLISH ICT D&T Key need 2: Making meaning The adolescent brain is specialising and pruning connections between brain cells that are not used or not viewed as ‘important’ to the person. This makes developing understanding and making meaning of learning a crucial aspect of adolescent learning. As teachers we ignore it at our peril and may ‘lose’ students who disengage from learning because of it. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at the University College in London, is well known for her work on the implications of neuroscientific research for education. She says that the brain ‘prunes’ connections like ‘you would prune a rose bush’ during adolescence. Dr Jay N Giedd (MD), currently Chief of the Unit on Brain Imaging in the Child Psychiatry of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) USA, launched a large scale study on child development in the 1990s that involved monitoring children with regular magnetic resonance scans up to the age of 16, which at that time, was the age presumed for full brain maturity. This study has since been extended in stages to age 30 and is still ongoing. It turns out that the brain is still maturing well into early adulthood and has been instrumental in sparking interest and research into the adolescent brain. The studies showed that the adolescent brain literally loses volume in the pre-frontal cortex as it is matures during the adolescent years (11–14). David Dobbs, in his article Beautiful Brains, National Geographic October 2011, quotes Dr Giedd: ‘. ..our brain undergoes a massive reorganization between our 12th and 25th years... as we move through adolescence the brain undergoes extensive remodelling, resembling a network and wiring upgrade.’ This implies that we need to support students in the middle years to make subject and personal meaning of their learning, or risk losing their new connections as part of this pruning process. The IMYC uses journaling and the Exit Point (Media Project) to encourage students to reflect on their subject learning from their own context; helping them to make personal meaning. From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 61 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Key Need 3: Taking risks and practising decision making in a safe environment We have probably all felt the frustrations of dealing with adolescent behaviour, in our classes and own families, who seem oblivious of danger and who seek excitement, novelty and risk above all else. For example, adolescents are heavily overrepresented in traffic accidents, generally caused by taking risks and involving alcohol or drugs. In his book The Learning Brain 2013, Dr Torkel Klingberg, professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the Stockholm Brain Institute, part of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, explains: ‘The decision-making process is determined by the reward system and pre-frontal cortex, which is able to evaluate signal, make plans and make decisions.’ Dr BJ Casey of the Sackler Institute in New York proposes explains that these two systems mature ‘out of step’ with each other, the reward system earlier than the prefrontal cortex. Dr Klingberg cites Casey: ‘This means that a teenager can have a relatively mature reward system but a relatively immature frontal lobe and therefore act differently to both children (in whom neither system is mature) and adults (in whom both systems are (hopefully) mature)’ Dr Laurence Steinberg in an article (Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspectives from Brain and Behavioural Science. 2004) illustrated this duality hypothetically: 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Age Fig. 1. Hypothetical graph of development of logical reasoning abilities versus psychological maturation. Although logical reasonong abilities reach adult levels by age 16, psychosocial capacities, such as impulse control, future orientation, or resistance to peer influence, continue to dewvelop into young adulthood. David Dobbs, in his article Beautiful Brains, National Geographic October 2011, states: ‘In scientific terms teenagers can be a pain in the ***. But they are quite possibly the most fully, crucially adaptive human beings around.’ He continues: ‘Teens take more risks not because they don’t understand the dangers but because they weigh risk versus reward differently.’ Dr Valerie Reyna, at the Centre for Behavioural Economics and Decision Research, at Cornell University Magnetic Resonance Imaging Facility, found that adolescents that have made risky 62 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E decisions generally understood the risks they were taking (most even overestimated the risk) but valued the perceived reward more highly than the risk. To explain this ‘sensitivity’ to reward Barbara Strauch, Medical Science editor of The New York Times, explains: ‘The brain of a teenager undergoes a proliferation of connections for dopamine, a neurotransmitter important for movement, alertness, pleasure-high levels that may have evolved to help...take necessary risks for survival, from exploring new fields for food or asking that saucy young girl to dance.’ This can also explain why most addictions also develop during adolescence. To support this argument further Dr Reyna, in her book The Adolescent Brain (2011), collected some very well respected studies on the adolescent brain and included her own study, ‘Judgement and Decision Making in Adolescence: Separating Intelligence from Rationality’ with Keith Stanovich, Richard West and Maggie Toplak. In their study the writers used what they called ‘fuzzy trace theory’ to explain how teenagers literally use different strategies to adults when faced with decisions, they even activate different brain areas and reward plays a much greater part in their decisions than inhibitions or self-control. From this and many other research studies into this phenomenon, it seems that adolescents do not view risk or make decisions in the same way as adults. Understanding how adolescents make decisions proves that we need to create opportunities for adolescents to practise decision making and take risks during their learning activities, but to do so in a safe environment. The subject tasks and the Exit Point in every IMYC unit offer many opportunities for students to practise decision making, encouraging and supporting students to take risks in a safe environment. Key Need 4: Adolescents need to work with their peers ‘The teen brain is similarly attuned to oxytocin, another neural hormone, which (among other things) makes social connections in particular more rewarding. The neural networks and dynamics associated with general reward and social interactions overlap heavily. Engage one, and you often engage the other. Engage them during adolescence, and you light a fire.’ David Dobbs continues in his article; ‘This helps explain another trait that marks adolescence: teens prefer the company of their own age more than ever before or after. At one level, this passion for same-age peers merely expresses in the social realm the teen’s general attraction to novelty: teens offer teens far more novelty than familiar ‘old’ family does. Yet teens gravitate towards peers for another more powerful reason: to invest in the future rather than the past.’ This sensitivity that adolescents seem to have for their peers’ influence is further illustrated by the effect that the presence of peers can have on risk taking. In 2013, Laurence Steinberg, professor of Psychology at Temple University, USA found in a simulated driving study that, ‘During adolescence, friends are so important that their presence activates the brain’s reward circuitry and that makes adolescents, under that condition, pay more attention to the potential rewards of a risky choice and less attention to the potential downside.’ From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 63 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E It is therefore very important to create collaborative learning opportunities, where students are learning with their peers; in small and bigger groups, groups they choose and those they do not. The IMYC offers countless opportunities for a wide variety of peer-enriched learning. Key Need 5: Adolescents need support with the transition from Primary to Secondary Education frontal lobe prefrontal cortex As mentioned earlier, Dr Giedd has proved that the adolescent’s ‘prefrontal cortex’, which controls executive functioning, is in flux; specialising and maturing during this important transition from primary school to the challenges of the secondary school environment. As a result, adolescents need extra support when it comes to the behaviours affected by the executive function, e.g. self‑organisation, forward planning, decision making and self-control. The story of Phineas Gage who, in 1848, while working on a railroad project in Vermont, experienced a severe brain injury when a three-foot-long, fourteen pound tamping iron was violently propelled through his skull, is well known and was the first to prove that the prefrontal area of the brain seems to control our executive function. (Phineas Gage: Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient, Steve Twomey, 2010, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ phineas-gage-neurosciences-most-famous-patient-11390067/?no-ist) Phineas was conscious and had a regular heartbeat when he arrived in at the hospital and he was reported to be ‘in full possession of his reason, and free from pain’ by the attending Physician. He was released to go home after 10 weeks and all seemed well, but while people who had known him before the accident described him as hard-working, responsible, and popular with his workers, he was suddenly prone to violet anger attacks and started drinking heavily, really struggling with self-control after the injury. He just was not the same man. Today, Gage’s skull and the tamping rod, which damaged it, are on permanent display at Harvard’s Countway Library of Medicine. The incident did much to advance the field of neurology, as it was among the first evidence suggesting that damage to the frontal lobes could alter aspects of personality and affect social skills and self-control. Before Gage’s brain injury, the frontal lobes were largely thought to have a small role in behaviour, we now know 64 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E that this very region of the brain known as the pre-frontal cortex is still developing and maturing during adolescence. ‘It’s sort of unfair to expect them (adolescents) to have adult levels of organisational skills or decision making before their brain is finished being built’ says Dr Jay Giedd, neuroscientist at the National Institute of Mental Health-PBS Frontline (2002) As mentioned earlier, his research included a very well-known study of thousands of MRI scans of persons between the ages of 5 and 25 which found that the pre-frontal cortex of the brain is the last to mature and undergoes specialisation from between the ages of 10 or 11 for girls and from around 14 or 15 for boys. For a film illustrating the maturation of the brain, developed by Dr Gied’s team at the Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda USA, (2009) from MRI scans clearly showing the pre-frontal cortex maturing during adolescence, watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gnm8f76zx0g The pruning process is shown in this clip and was constructed from MRI scans of healthy children and teens. The time-lapse movie compresses 15 years of brain development (ages 5-20) into just a few seconds. Red indicates more grey matter, blue less grey matter. The changes in colour from yellow/red to blue show the pruning process. Dr Klingberg summarises all the research eloquently in The Learning Brain, 2013: ‘The adolescent brain is not just a less experienced adult brain but an organ that is still under development.’ The IMYC provides a common learning cycle linking learning through a Big Idea, which is constant and familiar for students as they move from class to class giving the structure they need to support them through this state of flux. Recommended Booklist: The Learning Brain: Lessons for Education, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Blackwell, 2005 Introducing Neuroeducational Research, Paul Howard-Jones, Routledge, 2010 Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home and School, John Medina Pear Press, 2008 The Adolescent Brain: Learning, Reasoning, and Decision Making, Sandra B. Chapman, Michael R. Dougherty, Jere Confrey, Valerie F. Reyna, American Psychological Associations, 2012 (for academics) Brain Bugs: How the brain’s flaws shape our lives, Dean Buonomano, Norton, 2011 The Learning Brain: Memory and brain development in Children, Torkel Klinberg, Oxford University press, 2013 Developmental Neuroscience: Teenage Brains: Think Different? B. J. Casey (Editor), B. E. Kosofsky (Editor), and P. G. Bhide (Editor), Karger, 2014 (for academics) From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. 65 I M YC I M P L E M E N TAT I O N F I L E Articles: Beautiful Brains, David Dobbs, 2011. (Available to download from http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/print/2011/10/teenage-brains/dobbs-text) The Teenbrain: Insights from Neuroimaging, Jay N Giedd, 2008. (Available to download from http://brainmind.umin.jp/Jay_2.pdf) The Adolescent Brain, conversations with Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Simon Baron, 2012. (Available to download from https://edge.org/conversation/the-adolescent-brain) Social Influence on Risk Perception During Adolescence, Lisa J. Knoll, 2014. (Available to download from http://pss.sagepub.com/content/26/5/583) Phineas Gage: Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient, Steve Twomey, 2010, (Available to download from www.smithsonianmag.com/history/phineas-gage-neurosciences-most-famous-patient11390067/?no-ist) The Teenage Brain: Under Construction, Jane Anderson, 2011 (Available to download from https://www.acpeds.org/the-college-speaks/position-statements/parenting-issues/theteenage-brain-under-construction) The Adolescent Brain, BJ Casey, 2008. (Available to download from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2500212/) New understanding of adolescent brain development: relevance to transitional healthcare for young people with long term conditions, Allan Colver, 2013. (Available to download from http://research.ncl.ac.uk/transition/resources/Adol%20brain%20Published.pdf) Videos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gnm8f76zx0g National Institute of Health (2009): The pruning process is shown in this clip and was constructed from MRI scans of healthy children and teens. The time-lapse movie compresses 15 years of brain development (ages 5-20) into just a few seconds. Red indicates more grey matter, blue less grey matter. The changes in colour from yellow/red to blue show the pruning process. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zVS8HIPUng Ted: Sarah Jayne-Blakemore: Why do teenagers seem so much more impulsive, so much less self‑aware than grown-ups? Cognitive neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore compares the prefrontal cortex in adolescents to that of adults, to show us how typically “teenage” behaviour is caused by the growing and developing brain. http://brainsontrial.com/watch-videos/video/the-mind-of-the-adolescent/ 66 From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family. © WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission. INTERNATIONAL MIDDLE YEARS CURRICULUM 18 King William Street, London, EC4N 7BP T: +44 (0)20 7531 9696 F: +44 (0)20 7531 1333 E: members@greatlearning.com www.greatlearning.com/imyc The_IMYC InternationalMiddleYearsCurriculum From Fieldwork Education, a part of the Nord Anglia Education family ©WCL Group Limited. All rights reserved.