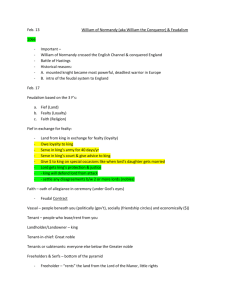

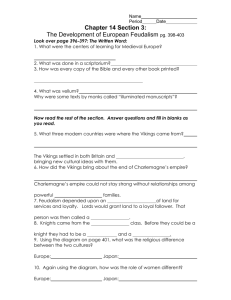

The Feudal System The Feudal System is a term conversed a lot in history. Some scholars often describe it as a certain political or economic system in the preindustrial times, but it has not been agreed that this system was in fact "feudal." This system is so vague and precise that historians consider it best to be avoided except in certain historical fields of study. The Feudal System has been describe as the political breakdown for gathering military power that supposedly started in Europe around the 19th century. Most historians that study medieval Europe consider it an inaccurate term that complicated instead of simplifying our knowledge of our past. Based on the medieval word feudum, reformers in the 18th century perfected the term feudalism to describe the system of rights and privileges controlled by the French government, especially regarding their landholdings and peasant tenants. In this sense, the Feudal System also became merged with manorialism or the organization of rural production into manors held by lords and worked by peasant labor. Historians usually cover more restricted views of this system. To them, it is mainly about gathering soldiers. To begin, a lord grants land to a vassal. In return, the vassal provides the lord a defined and limited term of military service, usually 40 days in one year and usually as a knight (a fully armed and armored horseman). Sometimes, the lord would provide armor and weapons for the vassal, but they vassal provided their own. The land was often a source of payment for their services. It was also known as "the knight's fee." The Feudal System has often been interpreted as the sign of a weak central government with limited cash resources. People were forced to substitute land for cash and to pass on power to its aristocracy. It is often seen as somewhat confusing. But not all separated polities raised troops using land-for-service deals, nor did all polities utilize such arrangements as weak or poor. These arrangements didn't even represent what has been regarded as the typical feudal society of northwestern Europe from the 9th to the 12th centuries. Recent studies have discovered modern ideas of feudal service to the terms and definitions of the Libri Feudorum, an Italian book written in the 12th and 13th centuries. Its explanation of fiefs and vassals became the basis for the 16th-century concepts of feudal institutions that have had controlled ever since. Service in return for land was limited as a basis for a military force. This system has been exaggerated as it being the source of medieval European armies. Soldiers did work for land, but often they lived with their lord and served him in military and nonmilitary situations. They were rewarded for long services with land of their own. Feudal service fits best on an informal basis: a lord in need of military support in local clashes and in serving his lord summoned together the young men who were his friends, relatives, hunting and drinking buddies, and they campaigned together, sharing the rewards of warfare. Social attachment in the lord's military household translated into military coherence, and constant hunting and fighting together imparted small unit skills. Legalistic terms of service played no role in these arrangements. There are also problems with defining feudalism more as a landed support system for unpaid military services. Individuals and groups also worked for pay in medieval Europe, wherever economic circumstances made it able even when they owed "feudal" service. Paid service became common after 1050. In a global background, there have been plenty of "soldiers' lands" in different times and places, in junction with paid and unpaid work. Some involved the king granting income rights over the land. Income rights were often given from several different pieces of land. Arrangements such as these, which involved no direct connection between the military manpower supported by landed income and the peasant manpower working the lands, differ fundamentally in type from arrangements in which the warrior who was granted the land assumed legal control over the peasant population and managerial control over the output of the estate. Indeed, in some cases the military manpower supported by designated "soldiers' lands" was not in a position of social and political dominance—it was not, in short, a warrior aristocracy, but instead constituted a sort of militia. Arrangements such as these also differ in type from those that were set up for a dominant warrior elite. Therefore, to call all land-for-service systems of supporting military manpower "feudal" is to arrive again at an overly broad definition, akin to the problem of the Marxist definition of feudalism, which makes no useful distinctions between systems and their characteristics. To try to distinguish some such systems as "feudal" while excluding others has inevitably involved privileging the characteristics of the European model to arrive at criteria for inclusion, for no reason than that it was studied (and called feudal) first—a pernicious instance of Eurocentrism. Military historians are thus increasingly avoiding the term, and are turning instead to functional descriptions of the world's (and Europe's) varied military systems of landed support, militia service, and the social hierarchies that accompanied them. . Feudalism is a much-contested term in world history. Scholars most often use it to describe certain political (and sometimes economic) systems in the preindustrial world, but they have not agreed on the characteristics that define a system as feudal. As a term that is paradoxically both too vague and too precise, an increasing number of historians consider it best avoided except in very restricted historical fields of study. Feudalism has most often been used to describe the political fragmentation and arrangements for raising military manpower that allegedly arose in Europe around the ninth century and theoretically persisted for many centuries thereafter. Most historians of medieval Europe, however—especially military historians, for whom the term should ostensibly be most germane— now consider it a misleading term that does more to obscure than to illuminate our view of the past. Though based on the medieval word feudum (Latin for fief), reformers in the eighteenth century coined the word feudalism to describe (unfavorably) the system of rights and privileges enjoyed by the French aristocracy, especially concerning their landholdings and their peasant tenants. This broad socioeconomic meaning was taken up and extended by Marxist historians, for whom the "feudal mode of production" succeeded the classical mode and preceded the capitalist mode. For military historians, this definition has always been far too broad. Indeed, if a privileged landholding class and a subject peasantry constitutes feudalism, then most civilizations before the industrial revolution were feudal, and the term loses its analytic usefulness. In this sense feudalism also becomes conflated with manorialism (the organization of rural production into manors held by lords and worked by subject peasant labor). Military historians have usually taken a more restricted view of feudalism. For them, it is the system of raising troops in which a lord grants a fief—typically a piece of land—to a vassal. In return, the vassal gave the lord a defined and limited term of military service, usually forty days a year and usually as a knight—a fully armed and armored horseman. Sometimes the lord provided the armor and weapons, but often the vassal provided his own. The fief was the payment for service and was also known as "the knight's fee." Feudalism in this sense has often been taken as the sign of a weak central authority with limited cash resources, forced to substitute land for cash and to devolve local power to its aristocracy; in fact feudal is often used simply as (somewhat misleading) shorthand for "decentralized polity dominated by a powerful warrior aristocratic class." But not all decentralized polities raised troops using land-for-service arrangements, nor were all polities that did utilize such arrangements weak, poor, or decentralized. Indeed, these arrangements did not even characterize what has been regarded as the prototypical feudal society of northwestern Europe from the ninth to the twelfth centuries. Recent research has traced modern conceptions of feudal service to the terms and definitions of the Libri Feudorum, an Italian legal handbook written in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Its academic view of fiefs and vassals became the basis for the sixteenth-century interpretations of feudal institutions that have held sway ever since. However, this picture of feudal service and the legalistic hierarchy of landholding rights associated with it does not fit the medieval evidence. Feudum and vassus were vague and mutable terms, and European military systems from the ninth to the fourteenth centuries were far more varied, flexible, and rational than conventional interpretations have supposed. Restricted service in return for granted land was inherently limited as a basis for a military force—leaders always needed soldiers available for more than forty days a year, at the least— and this system has been overrated as the source of medieval European armies. Soldiers did serve for land, but often they were "household knights"—young men who lived with their lord and served him in military and nonmilitary capacities—who were rewarded for long service with land of their own and served in anticipation of this reward. Even service for land already granted was far less defined and restricted than the traditional "forty days a year" formula implies. "Feudal" service (unpaid service by the vassals of a lord) worked best on an informal basis: a lord in need of armed support in his local disputes and in serving his lord (if he had one) called together the young men who were his friends, relatives, hunting and drinking companions, and social dependents, and they campaigned together, sharing the risks and rewards of warfare. Social cohesion in the lord's military household translated into military cohesion, and constant hunting and fighting together imparted small unit skills. Restrictive and legalistic terms of service played almost no role in such arrangements. There are also problems, however, with defining feudalism more generally as a landed support system for unpaid military service. First, individuals and groups also served for pay in medieval Europe from an early date, wherever economic conditions made it possible and even when they owed "feudal" service. Paid service became increasingly common in the period after 1050. Second, in a global context, there have been many forms of "soldiers' lands" in different times and places, in combination with paid and unpaid service. Some involved the granting, not of possession of a particular piece of land, but income rights over the land. Income rights were often, in fact, granted from several different pieces of land. Arrangements such as these, which entailed no direct link between the military manpower supported by landed income and the peasant manpower working the lands, differ fundamentally in type from arrangements in which the warrior who was granted the land assumed legal control over the peasant population and managerial control over the output of the estate. Indeed, in some cases the military manpower supported by designated "soldiers' lands" was not in a position of social and political dominance—it was not, in short, a warrior aristocracy, but instead constituted a sort of militia. Arrangements such as these also differ in type from those that were set up for a dominant warrior elite. Therefore, to call all land-for-service systems of supporting military manpower "feudal" is to arrive again at an overly broad definition, akin to the problem of the Marxist definition of feudalism, which makes no useful distinctions between systems and their characteristics. To try to distinguish some such systems as "feudal" while excluding others has inevitably involved privileging the characteristics of the European model to arrive at criteria for inclusion, for no reason than that it was studied (and called feudal) first—a pernicious instance of Eurocentrism. Military historians are thus increasingly avoiding the term, and are turning instead to functional descriptions of the world's (and Europe's) varied military systems of landed support, militia service, and the social hierarchies that accompanied them. Legal historians of high medieval Europe, on the other hand, can more confidently lay claim to the term feudal in their sphere of inquiry: in the more settled European conditions of the twelfth century and later, the informal arrangements of an earlier age tended to crystallize into formal legal arrangements with defined terms of service and inheritance rights on the part of the vassal. This process marked the decline of "feudalism" as a viable military system, but the rise of feudalism as a fundamental legal system. Indeed, the lord-vassal tie of landholding became crucial as one of two key bonds (along with marriage, which it resembled) among the European aristocracy. The twelfth-century English system of fief law became the basis of most later English estate law and thence of modern American property law. Feudal property law has a definite history, but perhaps because that history is so clearly tied to the specific times, places, and legal systems that generated it, legal historians—whose stock-intrade tends to be particulars rather than generalities—have not been tempted to see feudal property law as a transcultural historical phenomenon. The mistake for nonlegal historians is to read the legal history of high and late medieval Europe back into the political, military, and economic spheres of early medieval Europe, and then to extend that misreading to other areas of the world in the search for a general type of society. An example of such a historical misreading is provided by the study of "feudalism" in Japan between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. The dominance in Japan from Kamakura times of a rural warrior aristocracy in the context of somewhat weak central government has long invited comparison of Japan with medieval Europe, where similar conditions prevailed. Such comparisons have almost always been cast in terms of feudalism: since the traditional model of feudalism arose from the study of western Europe, looking for feudalism elsewhere risks shoehorning non-European histories into a European mold. This raises the possibility of misreading the evidence to find anticipated feudal characteristics, or, if a different trajectory is seen, of explaining what went "wrong" in the non-European case. This tendency has afflicted Western views of Sengoku Japan, the period during the sixteenth century when Japan was divided into warring domains headed by daimyos, or local lords. The feudal model has led many historians to see the Sengoku age as the epitome of feudal breakdown and anarchy. Daimyo domains are equated with the small castellanies and lordships of northern France, the feudal kingdom (French and Japanese) taken as the unit of comparison because of the prominence of weak central authority in the feudal model. By emphasizing the division of the larger political unit, however, this view obscures important forces of unity and political cohesion that were developing within the daimyo domains during this period. Without the feudal preconception, daimyo domains appear more readily as independent polities within a Japan that is more akin to Europe as a whole than to anyone kingdom within Europe. At a lower level of the feudal model, the European norm has inspired numerous comparisons of the structures of warrior society—for example of Japanese landed estates with manors, and of Japanese income rights, granted to warrior families by the central government in exchange for military service, with fiefs—that often obscure the important differences between the two societies more than they illuminate their commonalities. This problem, too, is most critical in the Sengoku age, when massive daimyo armies must be explained, in the context of the feudal model, in terms of a more "impersonal and bureaucratic feudalism" than existed in. "Bureaucratic feudalism" is a self-contradictory concept that dissolves on close inspection. Application of the feudal model to Japan has also invited the equating of terms that occupy analogous places in the model but that may not be so similar. The comparison of samurai to knights is the best example of this: the terms knight and samurai do not designate closely similar phenomena; the class connotations of the former make it closer to the bushi of pre-Tokugawa Japan. Equating samurai and knights also implies similarities between the fighting styles and techniques of the two kinds of warrior, when in fact their tactics differed significantly— especially, again, in the Sengoku age, with its samurai armies of disciplined massed infantry formations. The case of so-called feudalism in Japan thus serves as a caution against the hasty comparison of terms and models derived too narrowly from one culture. In short, "feudalism" in world history is a historiographical phenomenon, not a historical one. "Feudal" and "feudalism" are terms that have failed to cohere into agreed-upon concepts. They purport to describe a type of society that is valid across cultures, but describing the fundamental elements of such a society entails imposing a Eurocentric privileging of a European model that itself does not conform well to the most basic elements usual to a definition of the term. The alternative to clarity seems to be a broad definition of feudalism that fails to make useful conceptual distinctions among the societies to which the term is applied. As a result, it has become a term in decline.