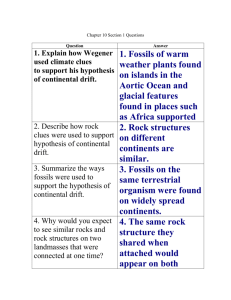

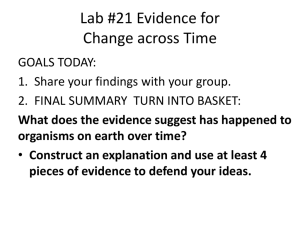

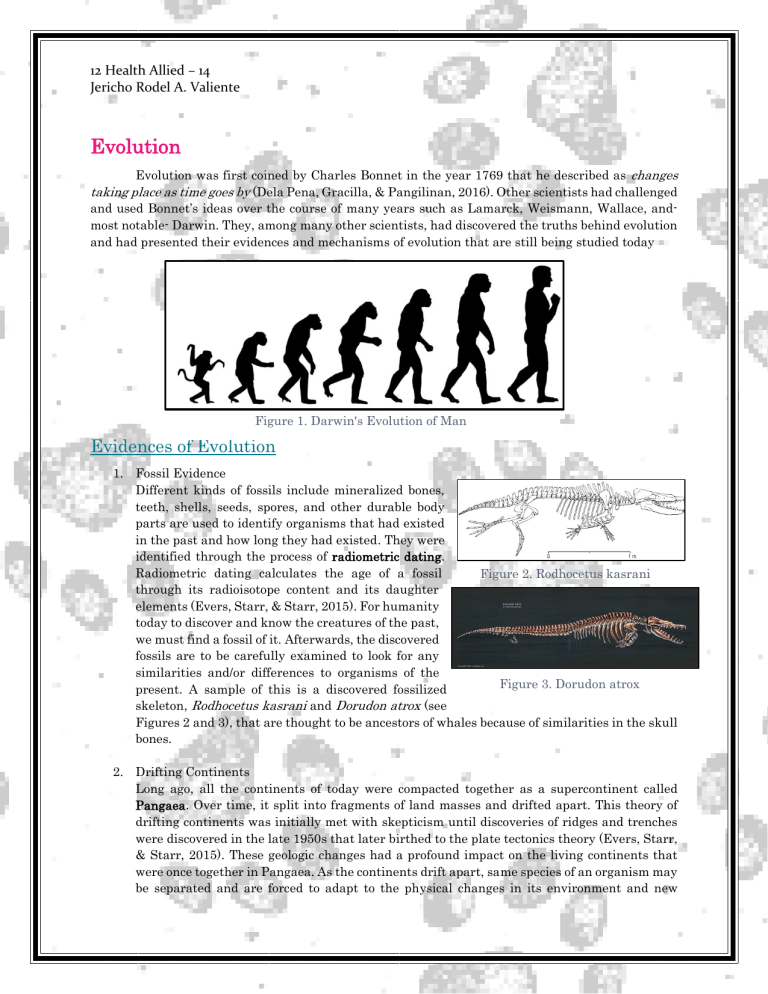

12 Health Allied – 14 Jericho Rodel A. Valiente Evolution Evolution was first coined by Charles Bonnet in the year 1769 that he described as changes taking place as time goes by (Dela Pena, Gracilla, & Pangilinan, 2016). Other scientists had challenged and used Bonnet’s ideas over the course of many years such as Lamarck, Weismann, Wallace, andmost notable- Darwin. They, among many other scientists, had discovered the truths behind evolution and had presented their evidences and mechanisms of evolution that are still being studied today Figure 1. Darwin's Evolution of Man Evidences of Evolution 1. Fossil Evidence Different kinds of fossils include mineralized bones, teeth, shells, seeds, spores, and other durable body parts are used to identify organisms that had existed in the past and how long they had existed. They were identified through the process of radiometric dating. Radiometric dating calculates the age of a fossil Figure 2. Rodhocetus kasrani through its radioisotope content and its daughter elements (Evers, Starr, & Starr, 2015). For humanity today to discover and know the creatures of the past, we must find a fossil of it. Afterwards, the discovered fossils are to be carefully examined to look for any similarities and/or differences to organisms of the Figure 3. Dorudon atrox present. A sample of this is a discovered fossilized skeleton, Rodhocetus kasrani and Dorudon atrox (see Figures 2 and 3), that are thought to be ancestors of whales because of similarities in the skull bones. 2. Drifting Continents Long ago, all the continents of today were compacted together as a supercontinent called Pangaea. Over time, it split into fragments of land masses and drifted apart. This theory of drifting continents was initially met with skepticism until discoveries of ridges and trenches were discovered in the late 1950s that later birthed to the plate tectonics theory (Evers, Starr, & Starr, 2015). These geologic changes had a profound impact on the living continents that were once together in Pangaea. As the continents drift apart, same species of an organism may be separated and are forced to adapt to the physical changes in its environment and new species it must coexist with. This, in turn, result to fossils of the same species being found in different locations that are now very distant with each other. The case of the Mesosaurus is a great example of this. Fossils of this organism were found in both South Africa and Eastern South America (refer to Figure 4). 3. Evidence in Form (Physiological Structure) This evidence refers to the similarities of body parts of between species of separate lineages or ancestors. Morphological divergence refers to homologous structures where body parts appear similar because they evolved from the same ancestor but have changed in its structure. An example of this suggests that many vertebrates have descended from ancient stem reptiles that had diversified over millions of years (Evers, Starr, & Starr, 2015). Morphological convergence, however, Figure 4. Fossils of Extinct Organisms refers to independent evolution of similar body parts found in different continents but of different lineages that are often called as analogous structures. An example of analogous structures between animals is the presence of wings. Many animals have wings and may have the same function, but their physiological appearances greatly differ from each other. A bird’s wings is different to a bat’s wings as it different to a dragonfly’s wings. 4. Evidence in Function In general, the more closely related animals are, the more signs of similarities would show in their development. An example of this is that all vertebrates undergo a stage in their development during which a growing embryo has four limb buds, a tail, and a visible endoskeleton that show the divisions of the body. They have similar patterns in embryonic development but the reason behind the difference in their adult stages is the different homeotic genes, called Hox, that mold the growing body in the early stages of development. For example, insects have a Hox gene called antennapedia that leads to a different growth in its embryo compared to other vertebrates. Figure 5. Embryonic Development of Vertebrates (Fish, Salamander, Tortoise) Figure 6. Mechanisms of Evolution Mechanisms/Processes of Evolution 1. Natural Selection a. Directional Selection – forms at one end of a range of phenotypic variation becomes more common over time b. Stabilizing Selection – an intermediate form of a trait is favored, and extreme forms are selected against c. Disruptive Selection – forms of a trait at both ends of a range of variation are favored, and intermediate forms are selected against d. Sexual Selection – focus on the matter of outreproducing because of better security in finding mates 2. Genetic Drift It is the change in allele frequency brought about only by chance. It makes nondistinctive populations particularly susceptible and vulnerable to the loss of genetic diversity. The concept of the founder effect and inbreeding are also related to genetic drift. If a small population establish a new one and does not have the original allele frequencies, then it will not be a representative or a direct descendant of the of the original. This outcome is called as founder effect and often, the species involved are closely related and underwent the process of inbreeding. Inbreeding refers to mating between two closely related organisms that are more harmful than not. 3. Gene Flow It refers to the movement of alleles between populations that may change or stabilize allele frequencies. This process of evolution is closely related to the genetic drift. However, gene flow focuses on how the transport of alleles (via food sources or chance) influence great changes in an organism. 4. Speciation This is the process of evolution where an entirely new species arise from countless mutations, genetic drift, gene flows, and natural selection. This is somewhat a mix of all other mechanisms and as such, it is a rare occurrence in the natural world. References Dela Pena, R. A., Gracilla, D. E., & Pangilinan, C. R. (2016). General Biology. Pasay City, Manila, Philippines: JFS Publishing Services. Retrieved August 17, 2019 Evers, C. A., Starr, C., & Starr, L. (2015). Biology Today & Tomorrow (Fifth ed.). Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Cengage Learning. Retrieved August 17, 2019