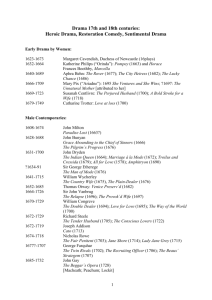

Literary Analysis for Drama 1 Literary Elements: create the story Theme Conflict Character Plot Setting Technical Elements: produce the drama Performance Elements: bring story to life on stage Script Speech Sound/Lighting Non-verbal Costumes actions Make-up Props Scenery Cast Structure of a Drama A drama is a written story performed by actors for an audience. A drama has many parts. FEATURES TO CONSIDER WHEN ANALYZING DRAMA • • • • • • • • • • Themes Information Flow Overall Structure Space Time Characters Types of Utterance in Drama Types of Stages Dramatic Subgenres Conflict Dramatic Texts Analysis Content Analysis Themes: Characters Space: dramatic environment (Word scenery, setting and characterization) Time Conflict Overall Structure Form Analysis Organization Conflict and ideas Information Flow Freytag’s Pyramid (plot) Dramatic sub-genre: comedy or tragedy External: acts and scenes Internal; actions Narrative techniques Types of Stage Types of Utterance in Drama: Monologue Dialogue Soliloquy Asides 4 Themes: Conflict and Ideas What the play means as opposed to what happens (the plot). Sometimes the theme is clearly stated in the title. It may be stated through dialogue by a character acting as the playwright’s voice. Or it may be the theme is less obvious and emerges only after some study or thought. The abstract issues and feelings that grow out of the dramatic action. Themes are describes using ABSTRACT NOUNS: love, hate, hypocrisy, etc 5 Questions to answer Analyzing Theme • What happens to the main characters? What do they learn? • What hints, if any, does the title give you about the author’s message? • What does the play demonstrate about people, values, or society? • What is the main message, or theme, of this play? 6 Characters • The characters in a play are divided into major characters and minor characters, depending on how important they are for the plot. A good indicator for it, is the time and speech as well as presence on stage. 7 Types of Characters Antagonist *Confidante *Dynamic character/ Round character *Flat character/static character *Foil *Narrator *Protagonist *Archetype *Sympathetic character *Unsympathetic character * 8 Questions to Answer Analyzing Characters • Who are the main protagonists—the heroes or most important characters? Who are the main antagonists—characters in conflict with the protagonists? (The antagonist can be an obstacle or a force of nature.) • What do you learn about the characters through their physical appearance (including costumes), actions, and speech? What do you learn from the comments of other characters? • How does each character react to other people or events? What do the reactions reveal about these characters, or about what they are reacting to? • If the play is a tragedy, what are the protagonist’s tragic flaws? • What reasons does each character have for acting as he or she does? 9 Space-Setting In George Bernard Shaw’s plays the secondary text ( all the texts surrounding the main text. Ex: (Title, scene descriptions, stage directions) provides details spatio-temporal descriptions. The stage set sets the scene(example poverty, ,misery, secrecy) Word scenery:As drama is multimedial, the visual aspect play an important role. The stage props described in secondary text help visualize the stage. The stage was created by word scenery. 10 Space-Setting Setting and characterization: the setting can be used as indirect characterization. A better look at the setting helps to understand better the characters’ background, or behavior. Characterizations made by the author in the play’s secondary text (authorial) or by characters in the play (figural), and whether these characterisations are made directly (explicitly) or indirectly (implicitly). 11 SPACE-SETTING Time: how are references to time made by the characters’ speech, stage directions, setting. Time in the story. Use of flashbacks and flashforwards. 12 Different Types of Conflicts 1. Character vs Character: • Characters are pitted against one another. • The antagonist (or other character) tries to keep the protagonist from reaching his goal. • The protagonist must overcome the efforts of the antagonist to reach his goal. 2. Character vs. Nature: • The hero must overcome a force of nature to meet his goal. • Nature can be a force of nature (like a storm, earthquake, or difficult climate) OR an animal from nature. • In literature, the hero sometimes meets his goal, but sometimes is defeated. 3. Character vs. Society • A protagonist sees something in a unique way. • People in his town or culture don't like his way of thinking. His bold ideas diverge from tradition or the rules. They ridicule and threaten him. He is compelled to act. • Our hero may convince the others he is right, but he might be forced to flee town. He may even lose his life. 4.Character vs. Self • The protagonist must overcome her own nature to reach her goal. The protagonist struggles within her own mind. The protagonist needs to overcome her struggle to reach the goal. She may, or may not, succeed. 13 Different Types of Conflicts 5. Character vs. Technology • The protagonist must overcome a machine or technology. • Most often the encounter with the machine or technology is through the character's own doing. For example, it may be technology or a machine that they created, purchased, or owned with the assumption that it would make their life easier. • Over time the protagonist must overcome the technology, in some instances, even destroying it before it destroys them. 6. Person vs. Supernatural Superficially, conflict with the supernatural may seem equivalent to conflict with fate or God, or representative of a struggle with an evocation of self (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) or nature (The Birds). But this category stands on its own feet as well. 14 Overall Structure Story and plot: As with the study of narrative texts, one can distinguish between story and plot in drama. Story addresses an assumed chronological sequence of events, while plot refers to the way events are causally and logically connected. Thus, plot refers to the actual logical arrangement of events and actions used to explain ‘why’ something happened, while ‘story’ simply designates the gist of ‘what’ happened in a chronological order. 15 Plot and Theme questions • Examine Plot • • What happens in the play? Use an Outline or Sequence Chain to record the • main events. • • What conflicts develop? Which are internal, and which are external—between • two people, people and society, or people and nature? • • What is the main conflict? • • How is the main conflict resolved? • Analyze Theme • • What happens to the main characters? What do they learn? • • What hints, if any, does the title give you about the author’s message? • • What does the play demonstrate about people, values, or society? • • What is the main message, or theme, of this play? 16 Questions to answer Explore the Setting • Where and when does the play take place? • What impact does the setting have on the events of the play? • What choices are suggested concerning set design, lighting, and props? Do you agree with these choices? Why or why not? 17 Freytag’s Pyramid 18 Freytag’s Pyramid Act I contains all introductory information and thus serves as exposition: The main characters are introduced and, by presenting a conflict, the play prepares the audience for the action in subsequent acts. The second act usually propels the plot by introducing further circumstances or problems related to the main issue. The main conflict starts to develop and characters are presented in greater detail. 19 Freytag’s Pyramid In act III, the plot reaches its climax. A crisis occurs where the deed is committed that will lead to the catastrophe, and this brings about a turn (peripety) in the plot. The fourth act creates new tension in that it delays the final catastrophe by further events. The fifth act finally offers a solution to the conflict presented in the play. While tragedies end in a catastrophe, usually the death of the protagonist, comedies are simply ‘resolved’ (traditionally in a wedding or another type of festivity). A term that is applicable to both types of ending is the French dénouement, which literally means the ‘unknotting’ of the plot. 20 Literary Elements INFORMATION FLOW • Usually there is no narrator. • The information is delivered through characters, stage or in the exposition • Exposition answers the readers’ WH questions. • Lack of information leads to keeping the reader interested in the play. 22 Dramatic Subgenre Comedy or Tragedy Ever since Aristotle’s Poetics, one distinguishes at least between two sub-genres of drama: comedy and tragedy. While comedy typically aims at entertaining the audience and making it laugh by reassuring them that no disaster will occur and that the outcome of possible conflicts will be positive for the characters involved, tragedy tries to raise the audience’s concern, to confront viewers with serious action and conflicts, which typically end in a catastrophe (usually involving the death of the protagonist and possibly others). 23 Types of Comedy Types of Comedy Sometimes, scholars distinguish between high comedy, which appeals to the intellect (comedy of ideas) and has a serious purpose (for example, to criticise), and low comedy, where greater emphasis is placed on situation comedy, slapstick and farce. There are further sub-genres of comedy: Romantic Comedy: A pair of lovers and their struggle to come together is usually at the centre of romantic comedy. Romantic comedies also involve some extraordinary circumstances, e.g., magic, dreams, the fairy-world, etc. Examples are Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream or As You Like It. Basics of English Studies, Version 03/04, Drama 133 Satiric Comedy: Satiric comedy has a critical purpose. It usually attacks philosophical notions or political practices as well as general deviations from social norms byridiculing characters. In other words: the aim is not to make people ‘laugh with’ the characters but ‘laugh at’ them. An early writer of satirical comedies was Aristophanes (450-385 BC), later examples include Ben Jonson’s Volpone and The Alchemists. Comedy of Manners: The comedy of manners is also satirical in its outlook and it takes the artificial and sophisticated behaviour of the higher social classes under closer scrutiny. The plot usually revolves around love or some sort of amorous intrigue and the language is marked by witty repartees and cynicism. Ancient representatives of this form of comedy are Terence and Plautus, and the form reached its peak with the Restoration comedies of William Wycherley and William Congreve. 24 Types of Comedy Farce: The farce typically provokes viewers to hearty laughter. It presents highly exaggerated and caricatured types of characters and often has an unlikely plot. Farces employ sexual mix-ups, verbal humour and physical comedy, and they formed a central part of the Italian commedia dell’arte. In English plays, farce usually appears as episodes in larger comical pieces, e.g., in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. Comedy of Humours: Ben Jonson developed the comedy of humours, which is based on the assumption that a person’s character or temperament is determined by the predominance of one of four humours (i.e., body liquids): blood (= sanguine), phlegm (= phlegmatic), yellow bile (= choleric), black bile (= melancholic). In the comedy of humours, characters are marked by one of these predispositions which cause their eccentricity or distorted personality. An example is Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His Humour. Melodrama: Melodrama is a type of stage play which became popular in the 19th century. It mixes romantic or sensational plots with musical elements. Later, the musical elements were no longer considered essential. Melodrama aims at a violent appeal to audience emotions and usually has a happy ending. 25 Types of Tragedy Senecan Tragedy: A precursor of tragic drama were the tragedies by the Roman poet Seneca (4 BC – 65 AD). His tragedies were recited rather than staged but they became a model for English playwrights entailing the five-act structure, a complex plot and an elevated style of dialogue. Revenge Tragedy / Tragedy of Blood: This type of tragedy represented a popular genre in the Elizabethan Age and made extensive use of certain elements of the Senecan tragedy such as Basics of English Studies, Version 03/04, Drama 134 murder, revenge, mutilations and ghosts. Typical examples of this sub-genre are Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy. These plays were written in verse and, following Aristotelian poetics, the main characters were of a high social rank (the higher they are, the lower they fall). Apart from dealing with violent subject matters, these plays conventionally made use of dumb shows or play-within-the-play, that is a play performed as part of the plot of the play as for example ‘The Mousetrap’ which is performed in Hamlet, and feigned or real madness in some of the characters. 26 Types of Tragedy Domestic / Bourgeois Tragedy: In line with a changing social system where the middle class gained increasing importance and power, tragedies from the 18th century onward shifted their focus to protagonists from the middle or lower classes and were written in prose. The protagonist typically suffers a domestic disaster which is intended to arouse empathy rather than pity and fear in the audience. An example is George Lillo’s The London Merchant: or, The History of George Barnwell (1731). Modern tragedies such as Arthur Miller’s The Death of a Salesman (1949) follow largely the new conventions set forth by the domestic tragedy (common conflict, common characters, prose) and a number of contemporary plays have exchanged the tragic hero for an anti-hero, who does not display the dignity and courage of a traditional hero but is passive, petty and ineffectual. Other dramas resuscitate elements of ancient tragedies such as the chorus and verse, e.g., T.S. Eliot’s The Murder in the Cathedral (1935). Tragicomedy: The boundaries of genres are often blurred in drama and occasionally they lead to the emergence of new sub-genres, e.g., the tragicomedy. Tragicomedies, as the name suggests, intermingle conventions concerning plot, character and subject matter derived from both tragedy and comedy. Thus, characters of both high and low social rank can be mixed as in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (1600), or a serious conflict, which is likely to end in disaster, suddenly reaches a happy ending because of some unforeseen circumstances as in John Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess (c.1609). Plays with multiple plots which combine tragedy in one plot and comedy in the other are also occasionally referred to as tragicomedies (e.g., Thomas Middleton’s and William Rowley’s The Changeling, 1622). 27 Organization External Structure Parts: Acts and scenes in the play. Dramatic Techniques: Monologue, dialogue, Soliloquy, asides. Theatrical Point of View: is the dialogue direct without intervention? Internal Structure Actions which take place in the drama 28 Organization- Narrative Techniques In drama, in contrast to narrative, characters typically talk to one another and the entire plot is carried by and conveyed through their verbal interactions. Language in drama can generally be presented either as monologue or dialogue. 29 TYPES OF UTTERANCES The written form of a drama is a script. The cast of characters is a list of who is in the play. Stage directions tell actors what to do; they are written in italic print. A scene has a fixed setting and continuous time frame. An act is made up of several scenes. Dialogue is the conversation between characters. A monologue is when one character speaks at length to another. A soliloquy is when a character is alone on stage and thinks aloud. Asides are spoken away from other characters, and a character either speaks aside to himself, secretively to (an)other character(s) or to the audience (ad spectatores). 30 Types of Stages http://www.theatrestrust.org.uk/discover-theatres/theatrefaqs/170-what-are-the-types-of-theatre-stages-and-auditoria 31 Bibliography https://www.google.com.ec/search?q=freytag%27s+pyramid&source=l nms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ei=bKLbU8vIBIHq8QGM8IGYDA&sqi=2&ved=0CA YQ_AUoAQ&biw=1366&bih=633 http://homepage.smc.edu/adair-lynch_terrin/ta%205/elements.htm http://www.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&c d=1&ved=0CBwQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lonestar.edu%2Fdepa rtments%2Flibraries%2FUniversityParkLibrary%255CAssignmentGde_E DUC2301_drama.pdf&ei=PazbU9WzHfPJsQTQtIDABA&usg=AFQjCNFjDU qaCJfC6guGvgimqE4iCmbZSw&sig2=HEuitJxvpb_gb1KnHDamg&bvm=bv.72197243,d.cWc http://www.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&c d=2&ved=0CCQQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww2.anglistik.unifreiburg.de%2Fintranet%2Fenglishbasics%2FPDF%2FDrama.pdf&ei=Paz bU9WzHfPJsQTQtIDABA&usg=AFQjCNGfiibMCDAzEfHi6d08ONafCrWmf A&sig2=BV0GvPWN20V4JqV8CVMjYQ&bvm=bv.72197243,d.cWc 32