Uploaded by

Yu-Chin Wen

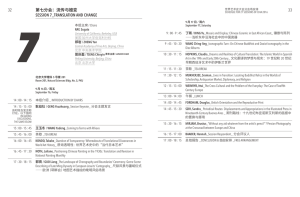

Doing Business in China: 2012 Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies