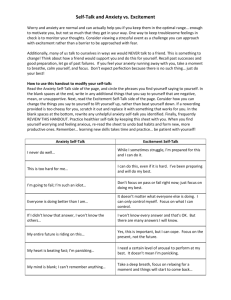

Stress, Anxiety, and Intervention Strategies. It is here! You are finally ready to return to your sport and get to show off all the hard work and progress that you have made up to this point. Your ACL feels ready to go, your body feels ready to go, but even though you feel physically ready, you may still feel like there is something missing. Maybe the thing that is missing is not necessarily pertaining to your ACL or something physical but seems more psychological. From what we understand and know about the rehabilitation process is that a full recovery means that you are both physically and psychologically recovered. In the return to sport stage when athletes are nearly one hundred percent recovered they are not necessarily dealing with physical problems but actually dealing with psychological issues due to low confidence, fear of re-injury or further injury, feelings of stress and anxiety due to lack of confidence of their physical condition, and even fear of returning to play. Does this sound more relatable to what you are dealing with? These fears, doubts, and low confidence can contribute heavily to stress which then affects your behavior and results in anxiety. Stress is your interpretation of the demands placed on you by internal or external stimuli and anxiety is the result of cognitively realizing you lack the ability to cope with those demands that result in psychophysiological reactions. According to Palmer and Dryden (1995) in the table of psychophysiological responses to stress that may be experienced by injured athletes there are seven different responses that could take place. Those seven include: Affective, behavioral, Biological/physiological, cognitive, imaginal, interpersonal, and sensory. Affective being anxiety, anger, guilt, depression, shame, and feeling sorry for oneself. Behavior being sleep disturbances, restlessness, aggressive behavior, alcohol or drug abuse, sulking, crying, poor performance, absenteeism, and clenched fist. Biological/Physiological being muscular tension, increased heart rate, indigestion, spasms in stomach, pain, and headaches. Cognitive being frustration, worries, distortion, exaggeration, unrealistic performance expectations, self-defeating statements, and self-handicapping. Imaginal being images of failure, images of re-injury, flashbacks of being injured, images of helplessness, and images of embarrassment. Interpersonal being withdrawal, manipulation, and argumentation. Sensory being tension, nausea, cold sweat, clammy hands, pain, and butterflies in stomach. Do any of these sound familiar? Now that you understand the different responses to stress it is important to include that all these negative responses fall under the umbrella of either Cognitive Anxiety or Somatic Anxiety. Cognitive anxiety being more of the negative mental and thought related stress responses. Somatic anxiety being more of the negative physiological responses to stress. The interrelationship between stress and anxiety and injury or re-injury have a strong correlation which has been supported through studies that prove that situation, circumstance, and the combination of stress and anxiety can all be determining factors. In moments when you are experiencing feelings of low confidence, fear, or are having doubts about your ability to perform at or above pre-injury level it can be debilitating and can lead to a significant amount of stress which then leads to anxiety which could then lead to injury, re-injury, or a possible set-back. The great news is that there are lots of stress and anxiety management interventions that we can learn, practice, and implement into our daily lives to help in moments when we begin to feel these negative emotions arising. These strategies will aid you in minimizing the risk of injury, re-injury, and help in prevention and treatment. Stress and Anxiety management programs have been shown to be effective in lowering athletes’ stress levels, decreasing negative thoughts, and increasing performance by providing techniques that help with the negative impact of stress by reducing the perceived demands of a situation, increasing your ability to cope with those demands, and providing techniques for the physiological responses of anxiety. When can you use these interventions? Before practice or workout, when starting to work on a range of motion or flexibility exercise, during an exercise, when experiencing pain, when experiencing a set-back, when experiencing feelings of low confidence or fears. So, what are some cognitive and somatic anxiety management interventions. Some techniques and the ones that we will go over in this chapter are self-talk, thought stopping, thought reframing, deep breathing, and PMR or progressive muscle relaxation. Self-talk What is Self-talk? Self-talk is any statement or thought made about yourself, a situation, or others that are either externally verbalized or through verbalizations that are made by a small voice in one’s head that acts as an inner dialogue that cannot be heard. Whether these statements or thoughts are internal or external they can be either positive and useful or negative and not useful. The main goals of self-talk are replacing the negative not useful thoughts or statements and telling ourselves positive useful thoughts or statements. Positive self-talk has been shown to increase self-esteem, motivation, attentional focus, and performance. Negative self-talk has been shown to be anxiety producing, counterproductive, self-demeaning, and critical. Examples of positive self-talk include: “I’ve felt this before” “I can do this” this type is more of a selfdirecting, encouraging, and a coping function. Examples of negative self-talk include “this is too much pain for me” I can’t do this anymore” “I give up” and it undermines yourself and your performance. One thing to keep in mind is that there are instances of Negative-self talk that can be useful but this is the type of self-talk is used to fire yourself up, to fuel effective workouts, and are thoughts or statements that can motivate you and give you a stronger desire to work harder and achieve your goals. An example would be “You idiot! Skipping this practice because you’re tired is not going to help you get closer to achieving those goals you have set!” When thinking about self-talk and how it influences our performance (Wiess and Weiss 1987) break it down into the four processes that take place that influence our self-talk and these are the what, think, feel, and do. The “what” refers to the setting, situation or circumstances that occur at practice, workout, or maybe even where the injury took place. The “think” is how you cognitively appraise the setting, situation, or circumstance and what you begin to tell yourself whether positive or negative that influences what happens next. The “feel” is completely reliant on how you viewed and appraised the setting, situation, or circumstance which either generated into positive or negative emotions. If they were stressful negative emotions of fear and low confidence it will then eventually lead to negative self-talk. This negative self-talk then directly affects what you decide to “do” and your attitude from then on which directly affects your ability to perform at your best. Another great example showing how self-talk influences performance is by (Hardy et al. 2009) and in the table created are four factors in which self-talk can influence your mind, motivation, how you behave, and its affect during a performance or sporting event. The table shows how manipulating these four areas can show an improvement in focus and concentration for the cognitive factor. Improvement in commitment to long term goals for the behavioral factor. Improvement in showing how positive self-talk can help focus in on detail to the execution of a technique which then positively affects performance. Then finally the affect in which describes how self-talk has influence on anxiety in sporting performance. The great thing about self-talk is that is completely in your control and you have the ability to use it to your advantage to improve your performance. Now that we understand the process of how self-talk works and understanding the correlation between positive self-talk and how it enhances performance, we now need to view self-talk in relation to its function. There are two types of positive self-talk and they both work great for different reasons and they will both benefit you but it’s important that you understand the differences between the two so you can we the situation or circumstances arises. Positive self-talk can be distinguished between instructional or motivational. Instructional self-talk according to (Hatzigeorgiadis, Theodorkakis, and Zourbanos, 2004; Theodorakis et al., 2000) aids you through precision-based tasks that require skill, timing, and accuracy to increase your attention and focus on the technical aspects of performance. Motivational self-talk is used for strength and endurance-based tasks that help in increasing effort, enhance confidence, and help to create positive moods. One great way that we can help with changing our self-talk is through using a technique called thought stopping. Thought stopping is used to initially stop an inappropriate thought and then allow a more functional thought to be used in its place. So how does it work? (Hardy et al. 2009) established three steps in order to improve your ability to thought stop. The first step that we need to take is to first identify and make you more aware of the inappropriate self-talk you are using. The second step and now that you are aware of when you use them and what words, thoughts, or statements that you use we then develop a trigger to STOP it. This can be done by using a cue word, image, or action. In step three we use a technique called thought reframing which is adopting a new or different way of explaining a situation by changing negative views to positive or productive views. Example: “I am still not sure if I can plant hard on my leg, I am afraid I might re-injure it. I need more rehab.” and you would replace it with, “My leg and ACL are now stronger than they’ve ever been. I’ve done the rehab, I’ve put in the work, I can do this, I am ready!” It’s important to remember that for any technique to work correctly you have to make sure that you 100% believe that it is going to work and that you are practicing it consistently and correctly. Now that we have covered techniques that help in dealing with cognitive anxiety, next we are going to introduce a technique that will help with dealing with somatic anxiety which are the negative physiological responses to stress. The purpose of us using relaxation techniques are to help with voluntarily decreasing the amount of tension in your muscles, to calm your mind, and decrease the heart rate and blood pressure. Relaxation techniques have also been shown to help with focus, attention, confidence, and to give you more of a sense of control. Our main focuses with these techniques especially in this return to sport stage is going to be to help with increasing confidence, increasing self-esteem, reducing anxiety, enhancing positive attitudes, and reducing tension. The technique we will be using in this manual is called progressive muscle relaxation. PMR is a very popular technique used in sport and is a form of deep muscle relaxation. The techniques purpose is to teach the individual how to focus on tensing, holding, and then relaxing a particular muscle or muscle group and gaining an understanding of what a tensed and relaxed muscle feels like. The result should be that body becomes less tense, your muscles slowly relax, which then reduce mental tension. The athlete typically holds the contraction for about five-ten seconds and relaxes for about twenty to thirty seconds then moves on to another muscle or muscle group. It also helpful to keep a very passive and relaxed attitude to free the mind of any thoughts or worries. A great time to use and practice this technique would be before practice, before a workout, or in times when feeling strong symptoms of stress and anxiety. An example showing of how we can work on different muscles and muscle groups and how to contract and relax them are in Table 14.3. It is important to note that before starting any relaxation exercise it will help to start with a deep breathing exercise. A deep breathing exercise will help calm and relax the body and mind and prepare it before we begin the progressive muscle relaxation exercise. The first step is to find a setting where you can get comfortable, free from distractions, and is quiet. Next, we want to make sure that we are not wearing any clothing that is going to any way distract us by making you feel uncomfortable, so I would recommend removing any clothing, jewelry, or shoes before sitting down and getting started. Next we want to either find a seat where we can sit up right where our body is not in a compromised position of leaning too far over or slouched or we can lay down on our backs where you can fully stretch out your legs and arms so we can make sure that we can get a full body of air throughout this exercise. Once you are comfortable you are going to start with either closing your eye or leaving them open, whatever is comfortable and begin with taking some deep breaths in through the nose and out through the mouth. While doing this it important to try to feel the air entering in through the nostrils and filling the abdominal region and feeling it grow with air and then feeling you stomach deflate as you follow the air out through the mouth and then repeating the process. With every breath out through the mouth muscles tension will begin to decrease. If you do find your mind wondering off or getting caught in thought just simply acknowledge the thought and gently bring your mind back to focusing on your breathing. The deep breathing can last as long as you need to help you get relaxed and in the right mind frame. Once you feel ready you can then go into the progressive muscle relaxation exercise. Below is a script to actually walk you through so you can see how it works and follow along. (Insert progressive muscle relaxation script.) Confidence One of the main reasons why we covered stress, anxiety, and how to cope in such detail and depth is because as we mentioned before, in the return to sport stage, psychological rehabilitation is now our biggest concern to ensure that you not only successfully recovered physically from your ACL injury, but mentally as well. In the return to sport stage it is common for athletes to show complete physical recovery but somehow still perform below their preinjury and competition level. From what we understand in readings out of (Taylor & Taylor ch.2 & ch.6) is that one of the main factors for not performing at the level that we should is because of low confidence. Low confidence can have a huge impact on our motivation, attitude, stress, and our overall performance which then lead to emotions of depression, anger, frustration, fear, doubts, negative self-talk, and anxiety. What does low confidence look like? Negative self-talk about rehabilitation outcomes, increased anxiety over return to pre-injury physical state which could then lead to tension and pain, low motivation and poor adherence behavior, overreacting to slow progress or plateaus in the program, and distracted focus from program goals. So, what is confidence and where does it come from? Confidence is like a muscle and we have to constantly work, practice, and develop ways to build this muscle and make it strong. Confidence is the feeling of self-assurance arising from the appreciation of your own abilities or qualities and comes from positive experiences which mold who you are and adds to your self-assurance. Confidence is a multi-dimensional factor that is developed through having program, adherence, physical, and return to sport confidence which are the four levels of confidence made by (Taylor & Taylor). Return to sport confidence is having a perception that the rehabilitation has been successfully completed, believing the injury is fully healed, having a sound level of overall physical conditioning, making sure techniques and tactics have been maintained, constantly and consistently working on maintaining positive levels of confidence, motivation, anxiety and focus, and being realistic and patient about progression from initial training to return to competition. Tips to improve confidence: remembering past performance accomplishments, watching and modeling the success of others, consistently training and practicing hard to build confidence through repetitions and preparation, acting confidently, thinking confidently, create a journal or success log to track what you did successfully during that practice or workout, and creating a list of positive statements that you can say to yourself before a practice or workout. It’s important to remember that when you do say these statement that you say them with conviction, strong belief, and say it in a way that is convincing to yourself and if someone else was listening to you. In example of this is the (Rehab Litany example) We have also provided a log and journals to write down and keep track of your past successful performances and progress so you can use these to fuel your confidence. Goal-setting At some point and time in your life as an athlete you, your coach, and teammates have set individual and team goals that you all have hoped to accomplish. Whether it was short-term goals that helped with getting day to day tasked accomplished at practice or of long-terms goals to go undefeated and win the championship there was a goal going into each day to give everyone some type of direction and motive. The rehabilitation process just like sports requires goal setting as well and it is very important that no matter what stage you are in you have shortterm and long-term goals. When thinking about making it is important to keep in mind that the goals you set are appropriate to your personal and physical needs but keeping in mind to follow the SMART goals principle. SMART stands for specific, measurable, adjustable, realistic, and that they are time-limited. Specific meaning that they are precise and establish clearly what you want to accomplish. Measurable meaning that you can somehow log, track, and measure, compare them to your bigger outcome goals. Adjustable meaning the goals are not necessarily concrete and can be modified if needed to if a set-back were to occur. Realistic meaning that the goals are difficult, challenging, yet achievable. Time-limited meaning that goals you do set can be achieve within a reasonable realistic amount of time. The benefits of goal-setting is that it clarifies the purpose for every action you make on a day to day basis. They provide a focus and a direction for workouts, practices, the rehab itself, and priorities. Goals set day to day behavioral expectations and establish clear and realistic targets for improvement, performance, and recovery. Goals also hold you responsible and help you build self-confidence by providing feedback for efforts and achievements. So how good are your goal setting skills? Let’s write them down. Are they S.M.A.R.T?