Overcoming math and science anxiety

advertisement

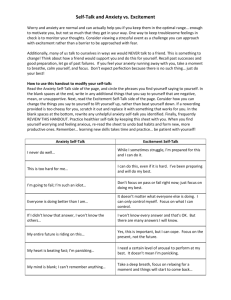

Overcoming math and science anxiety When they open books about math and science, some capable students break out in a cold sweat. These are symptoms of two conditions sweeping over students across the world- math and science anxiety. If you want to improve your math or science skills, you’re in distinguished company. Albert Einstein felt he needed to learn math to work on his general theory of relativity. So he asked a friend, mathematician Marcel Grossman, to teach him. It took several years. You won’t need that long. Think of the benefits of overcoming math and science anxiety. Many more courses, majors, jobs, and careers could open up for you. Knowing these subjects can also put at ease in everyday situations: calculating the tip for a waitperson, planning your finances, working with a spreadsheet on a computer. Speaking the languages of math and science can also help you feel at home in a world driven by technology. Many schools offer courses in overcoming math and science anxiety. It pays to check them out. The following suggestions can start you on the road to enjoying science and mathematics. Notice your pictures about math and science Sometimes what keeps people from succeeding at math and science is their mental picture of scientists and mathematicians. Often that picture includes a man dressed in a faded plaid shirt, baggy pants, and wing-tips shoes. He’s got a calculator on his belt and six pencils jammed in his shirt pocket. This is the guy who has never heard of the Rolling Stones. Such pictures are far from the truth. Succeeding in math and science won’t turn you into a nerd. Not only can you enjoy school more, you’ll find that your friends and family will still like you. Our mental pictures about math and science can be funny. At the same time they have serious effects. For many years, science and math were viewed as fields for white males. That excluded women and people of color. Promoting success in these subjects for all students is a key step in overcoming racism and sexism. Look out for shaky assumptions People often make faulty assumptions about how math and science are learned. They included: Math calls only for logic, not imagination If you can’t explain how you got the answer you’ve failed There’s only one right way to do a science experiment or solve a math problem If you don’t have a good memory, forget about science There is a magic secret to doing well in math or science These ideas can be easily refuted. To begin, mathematicians and scientists regularly talk about the importance of creativity and imagination in their work. At times they find it hard to explain how they arrive at a particular hypothesis or conclusion. Few of them boast about exceptional memories. And as far as we know, the only secret they count on is hard work. Get your self-talk out in the open and change it When students fear math and science, they often say negative things to themselves about their abilities in these subjects. Many times this self-talk includes statement such as: I’ll never be fast enough at solving math problems I’m one of those people who can’t function in a science lab I know this law of motion is really simple and I’m just too dumb to get it I’m good with words, so I can’t be good with numbers Faced with this kind of self-talk, you can take three steps. 1. Get a clear picture of such statements. When they come up, speak them out loud or write them down. When you get the little voice out in the open, it’s easier to refute it. 2. Next, do some critical thinking about these statements. Look for the hidden assumptions they contain. Separate what’s accurate about them from what’s false. Negative self-statements are usually base on scant evidence. They can often be reduced to two simple ideas: “Everybody else is better at math and science than I am” and “Since I don’t understand it right now, I’ll never understand it.” Both of these are illogical. Many people lack confidence in their math and science skills. To verify this, just ask other students. Remember that understanding in math and science comes in small steps over time. These subjects are cumulative-that is, each new concept builds upon previously learned concepts. Learning or reviewing those concepts promotes understanding. 3. Start some new self-talk. Use statements that affirm your ability to succeed in math and science: When learning about math or science, proceed with patience and confidence Any confusion I feel now will be resolved I learn math and science without comparing myself to others I ask whatever questions are needed to aid my understanding I am fundamentally OK as a person, even if I make errors in math and science Notice your body sensations Math and science anxiety are seldom just a “head trip.” They register in our bodies too. Examples are a tight feeling in the chest, sweaty palms, drowsiness, or a mild headache. Let those sensations come to the surface. Instead of repressing them, open up to them. Doing so often decreases their urgency. Next, learn and practice relaxation techniques. Many books, tapes, and courses exit on this subject. Make your text an A priority In a history, English, or economics class, the teacher may refer to some of the required reading only in passing. In contrast, math and science courses are often text-driven. That is, class activities follow the format of the book closely. This makes it doubly important to master your reading assignments. It’s crucial to master one concept before going to the next and to stay current with your reading. Read slowly when appropriate It’s ineffective to breeze through a math or science book as you would a newspaper. To get the most out of you text, be willing to read each sentence slowly and reread it as needed. A single paragraph may merit 15 or 20 minutes of sustained attention. Read chapters and sections in order, as they’re laid out in the text. To strengthen your understanding of the main ideas, study all tables, charts, graphs, case studies and sample problems. From time to time, stop. Close your book and mentally reconstruct the steps of an experiment or a mathematical proof. Read actively Science is not only a body of knowledge, it is an activity. To get the most out of your math and science texts, read with paper and pencil in hand. Work out examples and copy diagrams, formulas, or equations. You can also go beyond the text. Invent activities as you read. Construct additional problems similar to those in the book. Devise your own experiment to test the truth of a hypothesis. Relate your current reading to other math and science courses you’ve taken. Create your own charts and tables. Consider keeping a running record of you insights and questions, much like a journal. When reading your textbook or taking notes in class, use a two-page format. Summarize the reading or lecture on the right hand page. Record your guess, hunches, false starts, questions, and errors on the left. List what you don’t know yet and how you intend to find it out. Learn from specific to general A powerful way to learn many subjects is to get an overview of the main topics before you focus on details. You may want to us the opposite strategy when studying math and science. Learning these subjects often means comprehending one limited concept before going on to the next one. Through this kind of work, you gradually get the big picture. Jumping to general conclusions too soon might be confusing or inaccurate. Be gentle with yourself Learning science and math is like mastering any other skill. Some days your work can flow without effort and you’ll feel like a candidate for the next Nobel prize. On other days, you may stumble like a baby first learning to walk. That’s normal. Don’t be surprised if you feel you’re going backward once in awhile-as if something you used to understand so well seems like gibberish now. This can result from the way math and science concepts are presented: the rules and general principles often come first, followed by the exceptions and conflicting evidence. Think critically Science and math texts are not eternal truth. You’re free to ask questions or disagree with the author. If you do so, state your question precisely and base your disagreement on evidence. Remind yourself of the big picture Pause occasionally to get the big picture of the branch of science or math you’re studying. What’s it all about? What basic problems is the discipline trying to solve? How is this knowledge applied in daily life? For example, much of calculus has to do with finding the areas of “funny shapes”— shapes other than circles that have curves. Physics and calculus are used by many people, including architects, engineers, and space scientists. Ask questions fearlessly In any subject, learning comes when we ask questions. And there are no dumb questions. To master math and science, ask whatever questions will aid your understanding. Students come to higher education with widely varying backgrounds in these subjects. What you need to ask may not be the same as the other people in your class. Go ahead and ask. One barrier to asking questions is the thought, “Will the teacher think I’m stupid or illprepared if I ask this? What if she laughs or rolls his eyes?” With competent instructors, this will not happen. If it does, remember your reasons for going to school. The purpose is not to impress the teacher but to learn. And sometimes learning means admitting ignorance. Use lab sessions to your advantage Laboratory work is crucial to many science classes. To get the most out of these sessions, prepare. Know in advance what procedures you’ll be doing and what materials you’ll need. If possible, visit the lab before your assigned time and get to know the territory. Find out where materials are stored and where to dispose of chemicals or specimens. Bring your lab notebook and workshops to record and summarize your findings. If you’re collecting data during an experiment, keep in mind that there’s no such thing as a perfect measurement. Two people following the same instructions may come up with different results. When you chart or graph your results, your data points may not follow a straight line or smooth curve. Mathematical formulas are precise, while our measurements are approximations. If you’re not planning to become a scientist, the main point is to understand the process of science how science observe, collect data, and arrive at conclusions. This is more important than the result of any one experiment. SOURCE: BECOMING A MASTER STUDENT