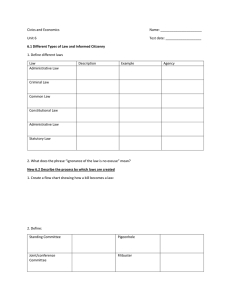

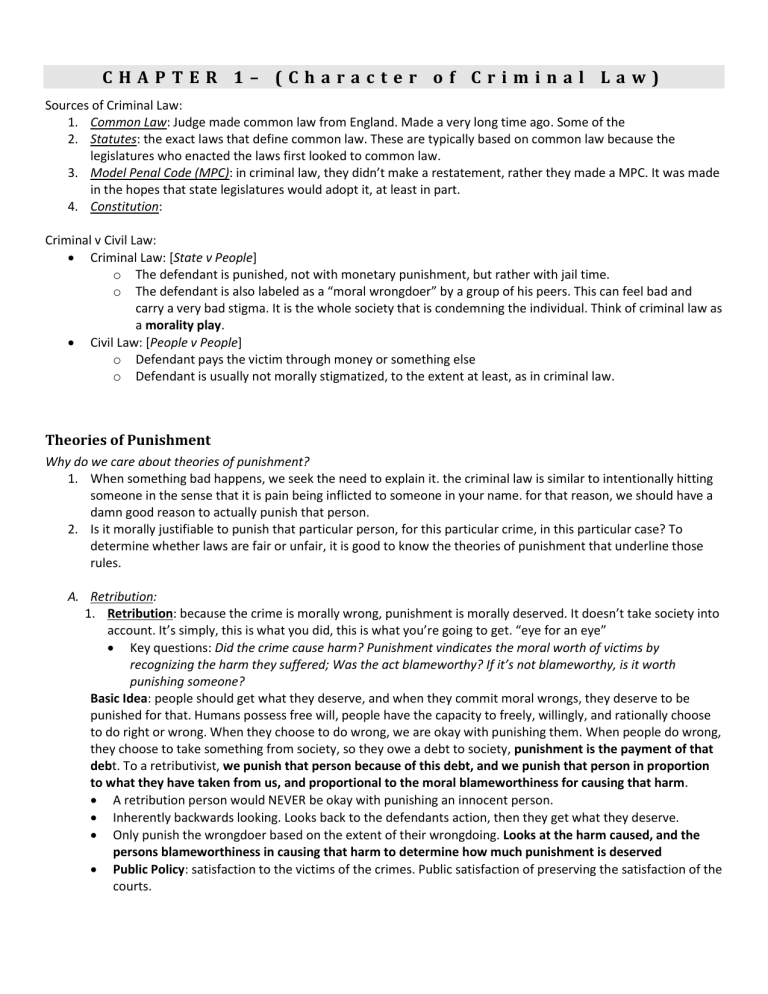

CHAPTER 1– (Character of Criminal Law) Sources of Criminal Law: 1. Common Law: Judge made common law from England. Made a very long time ago. Some of the 2. Statutes: the exact laws that define common law. These are typically based on common law because the legislatures who enacted the laws first looked to common law. 3. Model Penal Code (MPC): in criminal law, they didn’t make a restatement, rather they made a MPC. It was made in the hopes that state legislatures would adopt it, at least in part. 4. Constitution: Criminal v Civil Law: Criminal Law: [State v People] o The defendant is punished, not with monetary punishment, but rather with jail time. o The defendant is also labeled as a “moral wrongdoer” by a group of his peers. This can feel bad and carry a very bad stigma. It is the whole society that is condemning the individual. Think of criminal law as a morality play. Civil Law: [People v People] o Defendant pays the victim through money or something else o Defendant is usually not morally stigmatized, to the extent at least, as in criminal law. Theories of Punishment Why do we care about theories of punishment? 1. When something bad happens, we seek the need to explain it. the criminal law is similar to intentionally hitting someone in the sense that it is pain being inflicted to someone in your name. for that reason, we should have a damn good reason to actually punish that person. 2. Is it morally justifiable to punish that particular person, for this particular crime, in this particular case? To determine whether laws are fair or unfair, it is good to know the theories of punishment that underline those rules. A. Retribution: 1. Retribution: because the crime is morally wrong, punishment is morally deserved. It doesn’t take society into account. It’s simply, this is what you did, this is what you’re going to get. “eye for an eye” Key questions: Did the crime cause harm? Punishment vindicates the moral worth of victims by recognizing the harm they suffered; Was the act blameworthy? If it’s not blameworthy, is it worth punishing someone? Basic Idea: people should get what they deserve, and when they commit moral wrongs, they deserve to be punished for that. Humans possess free will, people have the capacity to freely, willingly, and rationally choose to do right or wrong. When they choose to do wrong, we are okay with punishing them. When people do wrong, they choose to take something from society, so they owe a debt to society, punishment is the payment of that debt. To a retributivist, we punish that person because of this debt, and we punish that person in proportion to what they have taken from us, and proportional to the moral blameworthiness for causing that harm. A retribution person would NEVER be okay with punishing an innocent person. Inherently backwards looking. Looks back to the defendants action, then they get what they deserve. Only punish the wrongdoer based on the extent of their wrongdoing. Looks at the harm caused, and the persons blameworthiness in causing that harm to determine how much punishment is deserved Public Policy: satisfaction to the victims of the crimes. Public satisfaction of preserving the satisfaction of the courts. B. Utilitarian types of punishments: [forward looking, care about the utility of punishment going forward, way the costs and benefits of punishment (factors looking at society, community, person)] Basic Idea: starts with the idea that all forms of pain are bad. Punishment for anyone is not good, and crimes are also not good. So society should punish the evil person, if that punishment would reduce the total future pain to a greater degree than allowing that person to go unpunished. The criminal is a rational calculator, the criminal will do a cost benefit analysis of the crime. He will look at what the potential punishment is, the benefit, and determine if the crime is worth the risk. A utilitarianism person MIGHT be okay punishing an innocent person, only if it would do more good than harm in the future. 1. Deterrence: punishment will set an example and send a message to the general public which will prevent future crime by deterring others. Society would be best if we prevented this crime. Key questions: will punishments send a message 2. Incapacitation: prevent future crimes by disabling this specific criminal. What is best for society is to lock this person up. It is rationalized only if the return to society is greater than the harm we are imposing on Jones, and greater than the pain we are imposing on society and Jones’s family. Key question: is this person dangerous? Will they do future crimes? 3. Rehabilitation: change the criminals to make them a more productive member of society. What is best for society is to fix this person. Key question: can the defendant be rehabilitated o [Costs to utilitarian punishment]: costs to society, cost to the community, cost to the family from the member who was convicted o Formula-will commit the crime if [ (reward for the crime * likelihood of obtaining the reward) > (Punishment for crime * likelihood of being punished) Usually not applicable to heat of the moment crimes, rather for crimes that require advanced planning Burden of Proof: All criminal cases require proof beyond a reasonable doubt: When we condemn someone, and take away their good name, we must establish a very high burden of proof. The government must establish the persons guilt in a criminal case beyond a reasonable doubt. The prosecutor must prove ever element being charged beyond a reasonable doubt. Due process requires that the prosecutor proves everything beyond a reasonable doubt. A. Reduces risk of error: reduces risk of erroneous convictions B. High stakes for the defendant: ∆ can face very bad punishments C. Social utility: much worse to convict an innocent person than to let one guilty person go free D. Legitimacy: public confidence in the criminal justice system E. Imbalance of power: gov has much higher resources than people F. Community stigma: people in the community really do not like people who are criminals G. Legitimacy: you want only the truth coming out Constitutional Limitations: 1. 8th Amendment [Cruel and Unusual Punishment] a. It is unconstitutional to criminalize merely being an addict (Robinson v California) b. You can punish actions that threaten public health and safety even if they are not voluntary (like being drunk in public, even if you are an addict, and you are homeless) (People v Kellogg) You can’t criminalize the condition, but you can criminalize the effects of the condition (he was in public threatening people and doing things which are punishable–retributive) 2. Proportionality [Sentencing] a. FROM SENTENCING SECTION 3. Fifth Amendment [Due Process] 4. Frist Amendment [Child Porn cases] 2|Page Statutory Interpretation: o Realist (Judicial power): Interpreted the statute pragmatically, to achieve sensible results that the public would support. Critiques: sometimes what the public wants is not what the public needs o Formalist (Legislature supremacy): interprets the statute in its formal meaning whatever the consiquences. The legislature is the person who makes the law, and we should follow that. Judges are robots who do it. Critiques: Precredit: previous decisions, especially the judge-created exception for self defense, seem incompatable with a rigid and literal interpretation of the text Unexpected results: following the text literally sometimes produces results the legislature would not approve, in situations the legislature never considered Counter majoritarian: a result that the public would appose. o Legal Process: you interpreted the statute with its original spirit not purley not in its literal text. Judges can fill in the gaps because judges cant guess every situation. Statutes often have multiple purposes or confecting purposes. legislatures are better equipped to decide what conduct is criminal. Whose by filling "gaps" in statutes, judges give legislatures incentives to punt short circuiting the democratic process. Case Rummel (1980) Sentence Life Parole? Yes, after 10 years Solem (1983) Life No Harmelin (1991) Life No Ewing (2003) Life After 25 years 3|Page Crime(s) Theft, after two nonviolent felonies Bad check, after six nonviolent felonies Possessing 570g of crack cocaine Shoplifting, after three burglaries and one robbery Result OK Violates 8th amendment OK OK CASES H. Who Defines Crimes? Regina v Dudley & Stephens–Queen’s Bench–1884 ∆’s lost at sea, two of them voted to eat another person who was on the verge of death to save themselves. Using common law reasoning, the defendants would be guilty of murder. The question before the court was whether or not they should bend the rules to allow the seamen to escape the death penalty. The court defined that it is best to deter this type of punishment, so they ruled that the seamen were guilty. Example of a Deterrence punishment Lon Fuller, The Case of the Speluncean Explorers Four defendants were trapped in a cave exploring accident. They drew sticks, the looser was eaten against their will. Approaches to Statutory Interpretation: o Realist (Handy): Interpret the statute pragmatically, to achieve sensible results that the public would support. If judges do this, they really won’t admit to it. do what the public wants, within reason. Critiques: o Formalist (Keen): Interpret the statute according to its natural meaning, whatever the consequences. The legislature is the person who makes the law, and we should follow that. Judges are robots who do it Critiques: Precedent– Previous decisions, especially the judge-created exception for selfdefense, seem incompatible with a rigid and literal interpretation of the text; Unexpected Results–Following the text literally sometimes produces results the legislature would not approve, in situations the legislature never considered; Countermajoritarian– No one doubts that the result reached through a literal reading of the text is democratically unpopular. o Legal Process (Foster): Interpret the statute consistent with its underlying “spirit” or purpose, not its literal text. Judges can fill in the gaps because the legislature can’t guess every situation. Critiques: Purpose-Driven Interpretation Is Lawmaking–leads us to pick a sole purpose, even though there might not be one sole purpose. Statutes often have multiple purposes, or conflicting purposes. Discerning the purpose of statutes is a choice, and thus a disguise for judicial lawmaking; Purpose-Driven Interpretation Is Impossible–Indeed, statutes often have no purpose besides legislators’ self-interest (public choice theory); Institutional Competence– Legislatures are better equipped to decide what conduct is criminal. Worse, by filling “gaps” in statutes, judges give legislators incentives to punt, short-circuiting the democratic process. Approaches to Seperation of Powers: 4|Page o Judicial Legitimacy (Handy): The power of courts depends on democratic approval. Judges should reach popular results, even if the decision process is political. o Legislative Supremacy (Keen): Only legislatures have the power and competence to make law. Judges are duty-bound to follow it, regardless of their own political or moral views. o Intelligent Servants (Foster): Legislatures cannot anticipate every situation. By interpreting statutes to advance the legislature’s purpose, judges do what the legislature would want. How should we define crimes: o Legislature: act prospectively. Are able to do research. Supreme in planning. o Courts: they decide cases on what Is criminal. They act retrospectively. They don’t have a lot of research. Important in application. o Defenses: People v Kellogg [what is the issue in this case?] ∆ is an addict, he was caught being drunk in public, he is arguing, based on a past case which ruled it was unconstitutional to punish addicts for being an addict, that it is unconstitutional to punish a homeless addict to be high/ drunk in public. Kellogg argues that the statute is “Unconstitutional as applied” as opposed to “Unconstitutional on its face” This is an application of a punishment is retributive argument: Kellogg has done something morally wrong (broken the law), so he deserves punishment for this. Powel v Texas: Outcome: You can punish actions that threaten public health and safety even if they are not voluntary (like being drunk in public, even if you are an addict, and you are homeless) Robinson v California: You can’t criminalize the condition, but you can criminalize the effects of the condition (he was in public threatening people and doing things which are punishable–retributive) Due Process: prohibits vague criminal defenses. The law needs to be understandable enough to deter (put on notice), and not so open that enforcement is arbitrary (City of Chicago v. Morales*) Nash v United States Welfare benefits stopped on notice of fraud; no hearing, based on anonymous tips “Unconstitutional on its face” due to vagueness issue Vague statutes are unacceptable not just because they deny a law-abiding person fair notice, but also because they “may authorize and even encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement” by police and prosecutors Defendant is excued from liability that the statute is so vague that people of common intelligence would not understand what the rule is Statutes with no “core” criminal act are usually vague, those with a core but have a “blurry edge” are probably going to be okay. A statute is "void for vagueness" and unconstitutional as a matter of due process, if it: o Fails to afford people of ordinary intelligence fair notitice sufficient to allow them to confirm their conduct to the law; or [due process issue] o Authorizes of even encourages arbitrarily or discriminatory punishment? [] Because of this decision, criminal statutes are free to use reasonableness standandards Connley v General Construction [sources of criminal law] Gray v Kohl [2(b) was unconstitutionally vague] Disability benefits stopped upon review of medical records Not a criminal case. Unconstitutional on its face. 2(b): requires that anyone who is on the school grounds without "legitimate business" will be in violation of subsection (2)(b)–this was held to be unconstutionally vague. o This is because they did define legitimate business. 5|Page 2(b) was saved because it doesn’t fail under pt 1, or pt 2 under the rule 2(b) was struck down, 2(c) was not struck down. It was too vague to know whether you were on notice or not Test: SLIDE 31 statutes are unconstitutionally vague if they fail to provide notice required to let normal people know what is prohibited; or may authorize or excuse arbitrary and discriminatory application of the law Absolute construction is not required The application itself must be whats argued over, you cant argue in the hypothesis of an application of a law Statutes are vunerable when over broad, high ration of unclear to clear, or liability turns on perception of others United States v Williams [sources of criminal law] Attachment to real property to secure pending/disputed tort proceeding Case about saving a statute. The last statute was held as vague Previous child porn act was vague. Four ways to save a statute [SLIDES] o Reasonable precision: due process requires only reasonable precision, not absolute certainty. Flexible standard are not permitted [Nash] o Saving construction: interpret narrowly to avoid problems of overbreadth. Constructing the statute to require scienter (a mental state) is especially common. o Defendant's actions: a person who engages in conduct that is certainly prosecuted [williams]. Even if the statute seems vague, lets push the vagueness question to another time o Settled meaning: statutory language that appears vague may have preexisting [nash?] Vagueness: [a common error on the exams is to automatically say its vague]. Signs statutes might be vague. [SLIDES] o Overbreadth: seems to apply to many harmless, constitutionally protected, conduct o High ratio of clear to unclear applications: if there is an obvious clear meaning to the statute its probably not vague. [# of clear / unclear applications] o Liability of defendant turns on perception of others [coats]: when the statute uses words that depend on other people’s reactions [do something that annoys people, doing something with no apparent purpose, ext.] Obscenity–sexually explicit speech with no socially redeeming value by reflecting to community standards. Substantial overbreadth: a criminal statute is unconstitutionally overbred in violation of the first amendment only if it is substantially overboard relative to its plainly legitimate sweep. Sentencing State v Thompson ∆ Charged with three counts of sexual assault, judge decided not to put him in jail bec hes small To determine if the sentence imposed is excessively lenient, we will look at: 1. The nature and circumstances of the offense; 2. The history and characteristics of the defendant; 3. The need for the sentence imposed: a) To afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct; b) To protect the public from further crimes of the defendant; c) To reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense; and d) To provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner; and 4. Any other matters appearing in the record which the appellate court deems pertinent. Four types of sentencing: 1. Indeterminate Sentencing: Judges are given essentially unlimited discretion to choose a sentence within a broad statutory range. Parole boards enjoy similar discretion to release offenders upon finding that they are rehabilitated. Cant be appealed Advantages: highly individualized, maximum flexibility for judges 6|Page Criticisms: unprincipled, judges’ intuitions vary widely serious risk of unwarranted disparity between similar situated offenders risk of discrimination, conscious or unconscious “soft on crime” “truth in sentencing”: 2. Guided discretion: Judges have broad discretion to sentence within statutory ranges, but guided by a statement of sentencing purposes that must be considered along with other factors that may not be considered. Appellate review may be available to correct outlier sentences. Advantages: highly individualized, substantial flexibility for judges, more coherent, shared set principles Criticisms: Purposes conflict, with no prioritization among them Disparity, other disadvantages of indeterminate sentencing 3. Statutory determination sentencing: judges have discretion to impose sentence within a statutory range, but must begin from a presumptive or advisory sentence (or group of sentences) within that range. The code may supply a non-exhaustive list of eligible aggravating and mitigating factors. Appelate review can correct outliers. Advantages: Starting point sentence increases consistency Appellate review can correct outlier sentences May be accompanied by abolition of parole and other “truth in sentencing” reforms Criticisms: advisory sentence may be arbitrary, may product unwarranted uniformity 4. Sentencing guidelines: A sentencing commission promulgates detailed rules for calculating a narrow sentencing range, based on the offense of conviction, the offender’s criminal history, and other factors. Judges have limited power to depart from the guideline range. Advantages: guidelines and appellate review promote consistency, expert agency can replicate existing practices or pursue other goals Criticism: too complex and time consuming, too inflexible too difficult to depart from guidelines too severe, especially with legislative meddling Ewing v California Π stole golf clubs from a sports store. when he was caught, it was his 4 th felony, and, due to the 3 strikes rule, he was sentenced to life, w/ parole after 25 years. Ewing’s 8th amendment cruel and unusual claim was ultimately unsuccessful. Sentence of 25 years to life imprisonment for shoplifting golf clubs is not grossly disproportionate as part of California’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” sentencing scheme for repeat offenders. The 8th amendment prohibits: o death sentences for particular offenses (Kidnapping, rape, child victim) and particular groups of people (juvenile (under 18), and intellectually disabled) o life in prison, without parole, prohibited for juvenile offenders in some circumstances (mandatory Life w/ out parole, offender not habitual (person can’t be changed), non-homicide offenses) o For noncapital sentences, the Eighth Amendment forbids only “extreme sentences” that are “grossly disproportionate” to the crime. Factors: gravity of the offense, gravity of the penalty, same crime in different jurisdictions, different crimes in same jurisdiction th o The 8 amendment allows states free to choose from various forms of criminal punishment In this case, Recidivism (repeat criminals) was the target of the 3 strikes rule. so, California can use this as grounds to justify the rule. 7|Page The Court does not sit as a “superlegislature” to second-guess the policy choices of lawmakers. Noncapital sentences are not grossly disproportionate so long as the state has a “reasonable basis” to believe that they advance its criminal-justice goals. When no single opinion is joined by a majority of Justices, the holding of the Court is the position taken by the Justices who concurred in the judgment “on the narrowest grounds.” o This sentence is permissible because it is not grossly disproportionate (3 votes) -This one Wins o This sentence is permissible because noncapital sentences can never be disproportionate (2 votes) o This sentence is grossly disproportionate in violation of the Eighth Amendment (4 votes) 8|Page