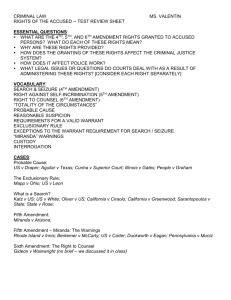

Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Investigation Fall 2018

advertisement