1.1 Persuasion and Arguments

advertisement

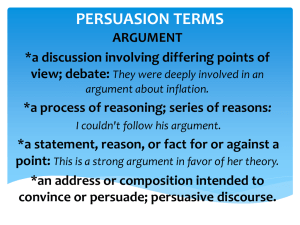

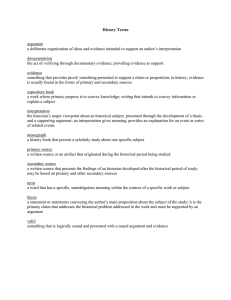

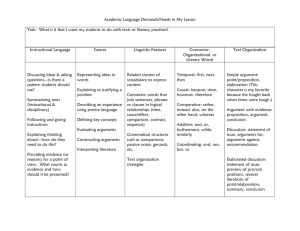

1 PHIL1300 Critical Thinking & Informal Logic 2016-2017 1 Introduction: Critical Thinking and Logic 1.1 Persuasion and Arguments In everyday discourse we come across messages telling us what to do or not do; what to believe or not believe. These messages are often packed in phrases such as: buy this soft drink, vote for Mr. X, don’t use drugs, don’t smoke, practice safe sex, abortion is murder, etc. Some of these messages we ignore, while some we unreflectively obey or unreflectively reject. Yet, others we might think about and question, asking “why should I do, or refrain from doing that?”, “Why should I believe that, or not believe it?” When we ask the “why?” we are asking for a reason or a justification for taking action or accepting the belief. However, some reasons or justifications are not good. So, for example, in answering the question “why should Adrian vote for Mr. X?” to give the reason that he (Adrian) should because Mr. X is his father’s friend is not a good reason. Another example: in answering the question “why is Mark a good sportsman?” to give the reason that it is because he is a registered student in the Sport Science program is not a good reason. To attempt to persuade by giving good reasons is the essence of argumentation. We encounter many different types of attempts to persuade, and not all of these are cogent arguments. Critical thinkers and logicians are basically interested in arguments that provide good reasons and more importantly in the determination of whether the reasoning involved is successful in providing us with good reasons for acting or believing. Some may find it surprising to think of an “argument” as a term for giving someone reason to do or believe something. This is because in most peoples’ experiences the word “argument” means or is associated with disagreement—shouting, insults, sulking, slamming doors, etc. This kind of argumentation is not the sort that interests critical thinkers and logicians. It should however be noted that critical and logical argumentation is not a monopoly of only renowned thinkers, it is not restricted to the works of only great philosophers such as Plato, Descartes, Hegel, etc. Indeed, critical and logical argumentation occurs frequently in ordinary everyday situations. It is found in newspapers, television and radio broadcasts, workplaces, etc. If one develops one’s ability to analyze people’s attempts to persuade so that one can accurately interpret what they are saying or writing and evaluate them, then one can begin to liberate oneself from accepting what others try to persuade one of without knowing whether one actually have a good reason to be persuaded. Some people are persuaded by what others say not because they have good reasons to believe, but because it is what they want to. Belief acquired in this way might lead to a life dominated by bad decisions and discontentment. It is for this reason that Socrates asserted the proposition that the 2 PHIL1300 Critical Thinking & Informal Logic 2016-2017 “unexamined life is not worth living.” While some may contest the truth of this Socratic dictum, it is fairly obvious that the only way one could find out the truth or cogency of any issue is to approach it from a critical and rational angle. Paying attention to arguments gets one, eventually, to the truth of a matter, thereby making the world and the thoughts of others easier to comprehend and deal with. Not all attempts to persuade are attempts to persuade using language by argument. Others are attempts to persuade by means of rhetorical devices. Any attempt to persuade by argument is an attempt to provide you with reasons for believing a claim. Arguments appeal to one’s critical faculties; they appeal to reason. Rhetoric, on the other hand, tends to rely on the persuasive power of certain words and verbal techniques to influence one’s beliefs. Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, amongst other demagogues, were good examples of persuasive rhetoricians; they appealed to people’s desires and prejudices rather than using arguments. When analyzing attempts to persuade one must perform the following three tasks: 1. The first stage involves distinguishing whether an argument is being presented. Here one needs to identify the issue being discussed, and determine whether or not the writer or speaker is attempting to persuade by means of argument. 2. The next stage (task) is that of reconstructing the argument with a view to express it clearly so as to demonstrate concisely the steps and form of the reasoning involved in the argument. 3. The third stage is evaluating the argument, inquiring what is good about it and what is bad about it. All arguments can be understood as attempting to provide reasons that some claim or proposition is true. A single claim (proposition), however, does not constitute an argument. Hence a single claim or proposition such as “It is going to rain” or “Philosophers are wise people” is not an argument. An argument needs more than one claim or proposition: It needs the claim (proposition) of which the arguer hopes to convince his or her audience, plus at least one other claim (proposition) offered in support of that claim. The cogency of the argument would then depend on whether or not one of the claims is supported by the other claim; if it is supported then the argument is cogent but if the support is lacking then the argument cannot be cogent.1 The reader should note that the reason why a single claim or proposition by itself cannot constitute an argument is because that claim (proposition) is unsupported i.e. no reasons are given. However, the lack of support in this case is somehow different from that of an argument that is not cogent. In the case of a non-cogent argument reasons are provided but it only turns out that they fail to serve the purpose of offering support. Hence, whereas with respect to single claims, the unsupported claims disqualify them from being arguments, in the latter case the unsupported claims disqualify them from being cogent. Though in both instances there is lack of support the reasons why are quite different. 1