HMP826

advertisement

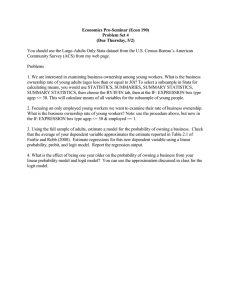

HMP 826 Applied Econometrics in Health Services Research Winter 2018 PROFESSOR Edward C. Norton, Ph.D. Professor of Health Management and Policy Professor of Economics M3108 SPH II ecnorton@umich.edu 734-615-5738 Office Hours: by appointment CLASS SCHEDULE Main lectures Problem sessions Mondays and Wednesdays 8:3010:00 am in room 2750 SPH I. Thursdays 1:302:30 pm in M1138 SPH II. Fridays 11:0012:00 am in M4318 SPH II. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is an introduction to applied econometrics in health services research using maximum likelihood estimation, the mathematical framework for the course. We will study econometric models in which the dependent variable is not continuous, including logit and probit, multinomial logit, ordered logit and probit, tobit, selection, two-part, and count models. The latter part of the course provides an integrated approach to specification tests. This course teaches how to choose the appropriate model, check the model specification, and interpret and present the results. Students will apply these techniques in weekly problem sets and an empirical term paper. COURSE MATERIALS The lecture notes, the basis of this course, are available at Dollar Bill, 611 Church St. Norton, EC. 2016. HMP 826 Class Notes: Applied Econometrics in Health Services Research. [The coursepack is printed in two parts.] Deb, P., E.C. Norton, and W.G. Manning. 2017. Health Econometrics Using Stata. Stata Press. Additional readings are on Canvas. Other resources may also be helpful. Cameron, AC and PK Trivedi. 2009. Microeconometrics Using Stata. StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. PREREQUISITES Economics 571 or equivalent, or permission by instructor. COURSE GOALS The goals of the course are related to the third CEPH foundational learning objective. The goals of this course are to understand how to 1. estimate and interpret logit, probit, and other maximum likelihood models; 2. build appropriate models in an MLE framework; and 3. test the model specifications. COURSE COMPETENCIES The course competencies are related to the second, third, and fourth CEPH foundational competencies for evidence-based approaches to public health. COURSE REQUIREMENTS, ASSIGNMENTS, AND GRADING The course grade will be a weighted average of performance in four areas. There will be weekly problem sets, a midterm exam, a final exam, and an empirical paper due in class on the last day of class. Grading: Problem sets Midterm exam Final exam Empirical paper Total 10% 30% 30% 30% 100% Problem sets, which are due on Wednesdays, will include a mix of written problems and computer assignments. Turn in a hard copy. The following simple grading scheme will be used for each problem: 2 points if entirely correct; 1 point if close to correct; 0 points if not close to correct. The empirical paper allows the students to demonstrate the skills learned throughout the semester. Students should start looking now for an interesting empirical question to answer and a data set that can be used to answer that question. The empirical paper is due in class on the last day of class. It will be given a letter grade with comments. CLASSROOM EXPECTATIONS AND ETIQUETTE Students are allowed and encouraged to collaborate on assignments (but not exams), unless instructed otherwise. To emphasize the importance of integrity 2 and intellectual property in the profession, on each assignment please list your collaborators. Academic misconduct will not be tolerated. DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION SPH is committed to creating classroom environments that are supportive of diversity, equity and inclusion. ACADEMIC INTEGRITY The faculty and staff of the School of Public Health believe that the conduct of a student registered or taking courses in the School should be consistent with that of a professional person. Courtesy, honesty, and respect should be shown by students toward faculty members, guest lecturers, administrative support staff, community partners, and fellow students. Similarly, students should expect faculty to treat them fairly, showing respect for their ideas and opinions and striving to help them achieve maximum benefits from their experience in the School. Student academic misconduct refers to behavior that may include plagiarism, cheating, fabrication, falsification of records or official documents, intentional misuse of equipment or materials (including library materials), and aiding and abetting the perpetration of such acts. Please visit https://sph.umich.edu/studentresources/mph-mhsa.html for the full Policy on Student Academic Conduct Standards and Procedures. STUDENT WRITING LAB The SPH Writing Lab is located in 5025 SPH II and offers writing support to all SPH students for course papers, manuscripts, grant proposals, dissertations, personal statements, and all other academic writing tasks. The Lab can also help answer questions on academic integrity. To learn more or make an appointment, please visit the SPH writing lab website. STUDENT WELL-BEING SPH faculty and staff believe it is important to support the physical and emotional well-being of our students. If you have a physical or mental health issue that is affecting your performance or participation in any course, and/or if you need help connecting with University services, please contact the instructor or the SPH Office for Student Engagement and Practice. Please visit https://sph.umich.edu/student-life/wellness.html for information on wellness resources available to you. 3 STUDENT ACCOMMODATIONS Students should speak with their instructors before or during the first week of classes regarding any special needs. Students can also visit the SPH Office for Student Engagement and Practice for assistance in coordinating communications around accommodations. Students seeking academic accommodations should register with Services for Students with Disabilities (SSD). SSD arranges reasonable and appropriate academic accommodations for students with disabilities. Please visit https://ssd.umich.edu/topic/our-services for more information on student accommodations. Students who expect to miss classes, examinations, or other assignments as a consequence of their religious observance shall be provided with a reasonable alternative opportunity to complete such academic responsibilities. It is the obligation of students to provide faculty with reasonable notice of the dates of religious holidays on which they will be absent. Please visit http://www.provost.umich.edu/calendar/ for the complete University policy. 4 COURSE TOPICS MAXIMUM LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATION Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Introduction and math review Maximum likelihood estimation [DNM Chapter 3] LOGIT AND PROBIT MODELS Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Logit and probit models Logit and probit estimation Logit and probit interpretation Interaction terms in non-linear models Log odds and ends Logit and probit models with panel data Logit and probit models with endogeneity [DNM Chapter 2] OTHER CATEGORICAL DATA MODELS Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 24 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Multinomial logit Extensions to multinomial logit Ordered logit and ordered probit Bootstrapping Tobit models Selection models Two-part models Count models [DNM Chapter 11] [DNM Chapter 7] [DNM Chapter 7] [DNM Chapter 7] [DNM Chapter 8] SPECIFICATION TESTS Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Introduction to specification tests Mathematics of specification tests LR tests Wald tests LM tests Hausman tests Endogeneity tests for binary outcomes 5 [DNM Chapter 4] [DNM Chapter 10] COURSE SCHEDULE: FIRST HALF January 3 January 5 Chapter 1 Introduction and math review No problem session January 8 January 10 January 12 Chapter 2 Maximum likelihood estimation Chapter 3 Logit and probit models Problem session January 15 January 17 January 19 Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, class will not be held Chapter 4 Logit and probit estimation Problem session January 22 January 24 January 26 Chapter 5 Logit and probit interpretation Chapter 6 Interaction terms in non-linear models Problem session January 29 January 31 February 2 Chapter 7 Log odds and ends Chapter 7 Log odds and ends Problem session February 5 February 7 February 9 Chapter 8 Logit and probit models with panel data Chapter 9 Logit and probit models with endogeneity Problem session February 12 February 14 February 16 Chapter 10 Multinomial logit Chapter 12 Ordered logit and ordered probit Problem session February 19 February 21 February 23 Chapter 24 Midterm No session February 26 – March 2 Bootstrapping Spring Break, classes will not be held 6 COURSE SCHEDULE: SECOND HALF March 5 March 7 March 9 Chapter 13 Tobit models Chapter 14 Selection models Problem session March 12 March 14 March 16 Chapter 15 Two-part models Chapter 15 Two-part models Problem session March 19 March 21 March 23 Chapter 16 Count models Chapter 16 Count models Problem session March 26 March 38 March 30 Chapter 16 Count models: two-part and zero-inflated Chapter 17 Introduction to specification tests Problem session April 2 April 4 April 6 Chapter 18 Mathematics of specification tests Chapter 19 LR tests Problem session April 9 April 11 April 13 Chapter 20 Wald tests Chapter 21 LM tests Problem session April 16 Chapter 22 April 25 Final Exam, 8:00 am – 10:00 am Hausman tests Empirical papers are due in class 7 COURSE TOPICS AND READING LIST Chapters 12. Maximum Likelihood Estimation Introduction and math review Chapter 1 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Chapter 3. (To introduce data for problem sets.) Duggan M. and S.D. Levitt. 2002. “Winning isn’t everything: Corruption in sumo wrestling.” American Economic Review 92(5):15941605. Maximum likelihood estimation Chapter 2 Chapters 39. Logit and Probit Models Logit and probit models Chapter 3 Logit and probit estimation Chapter 4 Logit and probit interpretation Chapter 5 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Section 2.5. Buchmueller, T.C., A.T. Lo Sasso, I. Lurie, and S. Dolfin. 2007. “Immigrants and employer sponsored health insurance.” Health Services Research 42(1):286310. (Probit) Interaction terms Chapter 6 Ai, C. and E.C. Norton. 2003. “Interaction Terms in Logit and Probit Models.” Economics Letters 80(1):123129. Greene, W. 2010. “Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models.” Economics Letters 107(2):291296. Karaca-Mandic, P., E.C. Norton, and B.E. Dowd. 2012. “Interaction terms in nonlinear models.” Health Services Research 47(1):255–274. Norton, E.C., H. Wang, and C. Ai. 2004. “Computing interaction effects and standard errors in logit and probit models.” Stata Journal 4(2):103116. Puhani. 2012. “The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in non-linear “Difference-in-differences” models.” Economics Letters 115(1):8587. Log odds and ends Chapter 7 8 Kleinman, L.C. and E.C. Norton. 2009. “What’s the Risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk ratios from nonlinear models including logistic regression.” Health Services Research 44(1):288302. Mood C. 2010. Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. European Sociological Review 26(1): 67–82. Norton, E.C. and B.E. Dowd. 2018. “Log odds and the interpretation of logit models.” Health Services Research 53(2):859878. Norton, E.C., M.M. Miller, L.C. Kleinman. 2013. “Computing adjusted risk ratios and risk differences in Stata” Stata Journal 13(3):492509. Logit and probit models with panel data Chapter 8 Norton, E.C. and C.H. Van Houtven. 2006. “Inter-vivos Transfers and Exchange.” Southern Economic Journal. 73(1):157172. (Chamberlain conditional logit) Zarkin, G.A., L.J. Dunlap, J.W. Bray, W.M. Wechsberg. 2002. “The effect of treatment completion and length of stay on employment and crime in outpatient drugfree treatment.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:261271. Logit and probit models with endogeneity Chapter 9 Angrist, JD and Krueger, AB. 2001. Instrumental variables and the search for identification: From supply and demand to natural experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15(4):6985. Basu, A and N Coe. 2015. 2SLS vs. 2SRI: Appropriate methods for rare outcomes and/or rare exposures. University of Washington working paper. Murray, M.P. 2006. “Avoiding Invalid Instruments and Coping with Weak Instruments.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(4):111132. Terza, J.V., A. Basu, and P.J. Rathouz. 2008. “Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: Addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling.” Journal of Health Economics 27(3):531543. Terza, J.V., W.D. Bradford, and C.E. Dismuke. 2008. “The use of linear instrumental variables methods in health services research and health economics: A cautionary note.” Health Services Research 43(3):11021120. Chapters 1016. Other Categorical Data Models Multinomial logit Chapter 10 Norton, E.C. and D.O. Staiger. 1994. “How hospital ownership affects access to care for the uninsured.” RAND Journal of Economics 25 (1): 171185. (Multinomial logit) Extensions to multinomial logit Chapter 11 9 Tay, Abigail. 2003. Assessing Competition in Hospital Care Markets: The Importance of Accounting for Quality Differentiation. RAND Journal of Economics 34(4):786815. (McFadden conditional logit) Ordered logit and ordered probit Chapter 12 Chaloupka, F.J. and H. Wechsler. 1997. “Price, tobacco control policies and smoking among young adults.” Journal of Health Economics 16(3):359373. (Ordered probit) Bootstrapping Chapter 24 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Section 11.3.2. Domino, M.E., C. Humble, W.W. Lawrence, and S. Wegner. 2009. “Enhancing the medical homes model for children with asthma.” Medical Care 47(11):11131120. Dowd, B.E., W.H. Greene, E.C. Norton. 2014. “Computation of Standard Errors” Health Services Research 49(2):731–750 Tobit models Chapter 13 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Section 7.6. Holmes, A.M., and P. Deb. 1998. “Provider choice and use of mental health care: Implications for gatekeeper models.” Health Services Research 33(5):12631284. Selection models Chapter 14 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Sections 7.1, 7.3, 7.5. Bundorf, M.K. 2002. “Employee demand for health insurance and employer health plan choices.” Journal of Health Economics 21(1):6588. (Heckman selection) Carmichael, F. and S. Charles. 2003. “The opportunity costs of informal care: does gender matter?” Journal of Health Economics 22(5):781803. (Heckman selection) Puhani, PA. 2002. The Heckman correction for sample selection and its critique. Journal of Economic Surveys 14(1):53–68. Two-part models Chapter 15 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Chapter 7. Belotti, F., P. Deb, W.G. Manning, E.C. Norton. 2015. “twopm: Two-part models.” Stata Journal 15(1):320. Stuart, B.C., J.A. Doshi, and J.V. Terza. 2009. “Assessing the impact of drug use on hospital costs.” Health Services Research 44(1):128144. Van Houtven, CH and EC Norton. 2004. Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics 23(6):11591180. Count models Chapter 16 10 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Chapter 8. Morgan, P.A., N.D. Shah, J.S. Kaufman, and M.A. Albanese. 2008. “Impact of physician assistant care on office visit resource use in the United States.” Health Services Research 43(5):19061922. Chapters 1723. Specification Tests Specification tests Chapter 17 & 18 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Chapter 4. LR tests Chapter 19 Cramer, JS and G Ridder. 1991. “Pooling states in the multinomial logit model.” Journal of Econometrics. 47(2/3):267-272. Wald tests Chapter 20 LM tests Chapter 21 MacKinnon, JG. 1992. “Model Specification Tests and Artificial Regressions.” Journal of Economic Literature. Vol. XXX:102146. Hausman tests Chapter 22 Endogeneity tests for binary outcomes Chapter 23 Deb, Norton, and Manning. Section 10.2.3. Blundell, R.W. and R.J. Smith. 1989. “Estimation in a class of simultaneous equation limited dependent variable models.” Review of Economic Studies 56 (1): 3757. Bolen, K.A., D.K. Guilkey, and T.A. Mroz. 1995. “Binary outcomes and endogenous explanatory variables: Tests and solutions with an application to the demand for contraceptive use in Tunisia.” Demography 32(1):111131. Rivers, D. and Q.H. Vuong. 1988. “Limited information estimators and exogeneity tests for simultaneous probit models.” Journal of Econometrics 39 (3): 347366. Smith, R.J. and R.W. Blundell. 1986. “An exogeneity test for a simultaneous equation Tobit model with an application to labor supply.” Econometrica 54 (3): 679685. 11 ADDITIONAL REFERENCES Additional references can be found online, including at the Stata Bookstore (www.stata.com). The following textbooks are focused on topics covered in this class. Deb, P., E.C. Norton, and W.G. Manning. 2017. Health Econometrics Using Stata. Stata Press. Greene, W.H. and D.A. Hensher. 2010. Modeling Ordered Choices. Cambridge University Press. Long, J.S. and J. Freese. 2001. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables using Stata. Stata Press. The following textbooks are good general textbooks in econometrics. Angrist, J.D. and J.-S. Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Cameron, A.C. and P.K. Trivedi. 2005. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press. Greene, W.H. 2011. Econometric Analysis. Seventh edition. Prentice-Hall. Kennedy, P. 2008. A Guide to Econometrics. Sixth edition. Blackwell Publishing. Wooldridge, J.M. 2009. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Fourth edition. South-Western College Publishing. Wooldridge, J.M. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Second edition. MIT Press. Additional interesting readings. Siegfried, JJ. 1970. A First Lesson in Econometrics. Journal of Political Economy 78(6):13781379. Fuchs, VR. 1986. Physician-induced demand: A parable. Journal of Health Economics 5(4):367. Kennedy, P. 2002. Sinning in the Basement: What are the Rules? The Ten Commandments of Applied Econometrics. Journal of Economic Surveys 16(4):569– 589. Smith, G. and J. Pell. 2003. Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: Systematic Review of Randomized Control Trials. British Medical Journal 327:1459–1461. Efron, B. 2013. A 250-year argument: Belief, behavior, and the bootstrap. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 50(1):129–146. 12