A Tale of Two Cities AUTHOR CRAFT

advertisement

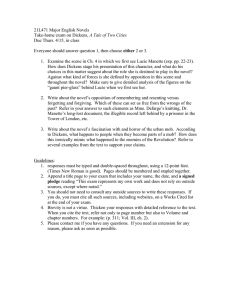

Analysis: Writing Style Master Puppeteer (and Major Chameleon) Charles Dickens is the King of Style. We’ll say that again: when it comes to style, Charles Dickens is the King. He’s the grand-daddy of all great fiction writers. The best stylist you’ll probably ever read. Here’s why: Dickens is the master of manipulating language to make scenes come alive. Not only does he describe scenes in vivid detail, but the very sentences he writes mimic the way the scenes themselves come to life. For example, when he wants to emphasize how long-winded and boring the court system can be, he spends five pages recounting a lawyer’s argument. Every single sentence of the lawyer’s speech begins with the word "that." "That, his position and attitude were, on the whole, sublime. That, he had been […]" (2.1.1). Get the picture? By the time we’re halfway through reading the speech, we wish the whole thing were over and done with. We’re almost bored out of our minds. And that, friends, is exactly what Dickens wants us to be. When things heat up, however, his style becomes as choppy and chaotic as the violence that rolls through the streets of Paris. The Storming of the Bastille is described like this: Deep ditches, double drawbridge, massive stone walls, eight great towers, cannon, muskets, fire and smoke. Through the fire and through the smoke—in the fire and in the smoke, for the sea cast him up against a cannon, and on the instant he became a cannonier. (2.21.40) Short phrases emphasize the movement that’s going on all around Defarge. Repeated phrases emphasize the way that fire and smoke seem to take over the entire world. For Defarge, there’s nothing outside of the present moment of battle. As we get drawn into the sped-up rhythm of Dickens’s sentences, there’s nothing outside of Defarge’s battle for us, either. Oh, and since we’re talking about repetition, we should mention that Dickens is a big fan of it. Remember "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times […]" and "It is a far, far better thing I do […]; it is a far, far better rest I go to […]"? The novel begins and ends with phrases that would have made Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., proud. Repetition forces us to realize just how important the phrases we’re reading are. After all, we read them again and again. Analysis: Tone Take a story's temperature by studying its tone. Is it hopeful? Cynical? Snarky? Playful? Satirical; Journalistic; Moralistic Fanboy-ing out on Thomas Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution, Dickens decided to try his hand at historical fiction. It wasn’t something that he often did. In fact, A Tale of Two Cities is one of two historical novels that Dickens wrote... and he wrote a lot of novels. His style in A Tale of Two Cities is actually pretty remarkable, if only because it’s so different from most of his other works. Dickens has gone down in history as a writer whose skill with humor and satire allowed him to make all sorts of social critiques. A phrase from Mary Poppins might just describe Dickens’s method best: "A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down." Because his books were funny social critiques, audiences ate them up. On Fire With Satire The first volume of A Tale of Two Cities does contain some of this satire: see, for example, Dickens’s description of the court case in England. It’s so over-the-top that it begins to be ridiculous (and ridiculously funny). Here’s an example of the lawyer’s argument in favor of executing Charles Darnay: That, for these reasons, the jury, being a loyal jury (as he knew they were), and being a responsible jury (as THEY knew they were), must positively find the prisoner Guilty, and make an end of him, whether they liked it or not. That, they never could lay their heads upon their pillows; that, they never could tolerate the idea of their wives laying their heads upon their pillows; that, they never could endure the notion of their children laying their heads upon their pillows; in short, that there never more could be, for them or theirs, any laying of heads upon pillows at all, unless the prisoner's head was taken off. (2.3.1) It’s a serious subject, sure, but it’s also good for a laugh. More important, spinning out court procedures to ridiculous lengths allows Dickens to demonstrate how, well, ridiculous the judicial system actually is. Once Dickens moves into describing the events leading up to the French Revolution, however, his tone takes a 180º turn. He’s building up the work of Carlyle, who tried to make the French Revolution into something of a family drama. For Dickens, this means that there aren’t too many funny characters whom he can satirize (like, for example, the Crunchers) in France. We know that spousal abuse isn’t actually funny. For Dickens’s readers, however, it was. It’s sort of like a Punch-and-Judy show. Everyone thought it was hi-larious. France Ain't No Laughing Matter But in France, there's no Crunchers. No laughs. Instead, we get a pretty journalistic approach to the oncoming violence. Here’s an example of his language in the last volume: One year and three months. […] Every day, through the stony streets, the tumbrils now jolted heavily, filled with Condemned. Lovely girls; bright women, brown-haired, black-haired, and grey; youths; stalwart men and old; gentle born and peasant born; all red wine for La Guillotine, all daily brought into light from the dark cellars of the loathsome prisons, and carried to her through the streets to slake her devouring thirst. Liberty, equality, fraternity, or death;—the last, much the easiest to bestow, O Guillotine! (3.5.1) Perhaps the most startling aspect of Dickens’s depiction of the revolution is his insistence on recounting the violence just as it occurred. There are rarely any moments of comedic relief in the last sections of the novel. What we do get, however, are some bird’s-eye (or God’s-eye) views of the scenes playing out below us. See our analysis of the "Narrator Point of View" for more details about that. Briefly, though, we’ll just say that Dickens can’t seem to resist throwing in a few moral opinions every now and then. Since he can’t satirize mass violence and death, he chooses to offer us a few short lessons on the subjects instead. Analysis: Narrator Point of View Who is the narrator, can she or he read minds, and, more importantly, can we trust her or him? Third Person Omniscient Dickens likes to play the Voice of God. His narrator tends to know it all. Not in a bad way—it’s more like the voice of your favorite high school teacher and Oprah all rolled into one. See, for example, the sweeping statements of the first chapter of the book: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair [...]. (1.1.1) As you can probably tell from his opening foray, Dickens’s narrator is a big-picture sort of guy. We’re going to get the whole world packed into one novel, which is why it’s lucky that our narrator seems to know exactly what’s going on. All the time. This, friends, is no modernist text. There’s a clear (if complicated) plot. It develops in exactly the way that our narrator expects it to. And believe us, we’re going to need all the help we can get to navigate through the complicated web of historical social uprisings, long-kept family secrets, and unspoken allegiances. Luckily, Dickens’s narrator knows exactly where he’s taking us. He lets us into the minds of characters whenever it seems prudent for him to do so. Why So Serious? Having said that, though, we’ve got to wonder: why do we get to hear so much about what’s going on in Carton’s head and so little about what's in Darnay's? We understand why it’s important to be inside the doctor’s head (if only because it shows us just how crippling a long prison stay can be), but why do we hear almost nothing at all about Lucie’s thoughts? Dickens seems to be strategically making some characters more accessible to us than others, and we’re pretty sure that he has reasons for his choices. These are all good—and big—questions. Unfortunately, we don't have Dickens around to give us the answers. We do think, however, that our narrator is playing with our emotions just a little bit. That letter from Doctor Manette? It’s like when Oprah pulls out that big, tear-jerking surprise at the end of a family reunion episode. How can we know so much about Doctor Manette and still not know this? It’s almost as if Dickens is playing a big game of "Gotcha." Just when we think we know it all, his narrator manages to pull a few tricks out of his bag. That’s why we’re saying he does a pretty decent job of playing God. It’s his world. Make sure you remember that. Wine/Blood Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory There Will Be... Wine? Dickens isn’t exactly placing this metaphor delicately into his readers’ hands. He’s shoving it down our throats. If you missed the part where he warns us that blood will soon spill in the streets like wine, check out most of Volume I again. We promise you, it’s easy to find. There are snippets like this one spilled throughout the chapter like wine (or blood): The time was to come, when that wine too would be spilled on the street-stones, and when the stain of it would be red upon many there. (1.5.5) Using the wine that spills into the streets early in the novel as a metaphor for the blood spilled in the revolution serves a practical purpose: the Defarges run a wine shop. The Defarges are the hub of revolutionary activity. It all fits together neatly. Blood Drunk More importantly, allowing wine to stand in for blood allows Dickens to hint at the fatal flaws in the revolutionaries’ plans: too much wine makes people drunk and often more than a little crazy. A few glasses too many, and suddenly you’re not thinking nearly as well as you probably should be. Similarly, spilling a little blood makes people hunger for more. Suddenly, it’s not enough to kill the people who’ve wronged the poor. It’s also pretty fun to kill their wives, their sons, their daughters, and that guy that people once saw standing next to them. See how things can get out of control? La Guillotine becomes a glutton, demanding more and more wine to satiate its evergrowing thirst. Revolution may be a great idea theoretically. According to Dickens, however, it just gets you too drunk too fast. Violence, folks, is not the answer. Golden thread Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory Good As Gold Lucie is the "golden-haired doll" who charms just about everyone she meets with her beauty. She’s got yellow hair, as you’ve probably guessed. More interestingly, however, Dickens uses her hair color as an image that binds her family together. She becomes the "golden thread" that unites her father with his present, not allowing him to dwell too much on the horrors of his past: She was the golden thread that united him to a Past beyond his misery, and to a Present beyond his misery: and the sound of her voice, the light of her face, the touch of her hand, had a strong beneficial influence with him almost always. (2.4.3) A golden thread almost sounds like some sort of magical power; in fact, the Manettes lead a "charmed" life in Soho. Lucie may not be the character who gets the most screen time in this novel, but Dickens makes sure that we all know she’s its heart. Lucie unites Sydney to Charles, Doctor Manette to Charles, and Mr. Lorry to the family in general. Lucie becomes the reason that Charles escapes the grasp of the Republic’s "justice." In one terrifying moment in the novel, Jacques Three speculates about how wonderful it would be to see her golden hair on the chopping block of La Guillotine. The charm of Lucie’s influence, however, makes this an impossibility. Mr. Lorry and Sydney are determined to save her at any cost. Guess being a blonde has some good points, after all. Monseigneur Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory Chara-llegory Monseigneur is a character. He’s also an allegory. Wait, how can a character be both a character and an allegory? Well, Dickens describes Monseigneur as a member of the aristocracy. It becomes pretty clear, however, that "Monseigneur" also becomes a shorthand way for Dickens to refer to the aristocracy as a class. For example, when the narrator spends a good portion of a chapter describing how Monseigneur takes his hot chocolate, we could be reading about one man. When we read, however, that "Monseigneur, as a class, had dissociated himself from the phenomenon of his not being appreciated" (2.24.3), it seems fairly self-evident that we’re reading about more than one individual. In fact, we’re reading about an entire class of people. Why the blurring between individual and class? Well, for one thing, it allows Dickens to describe an entire group of people rather quickly. Once we know how picky and self-satisfied Monseigneur is when he drinks his chocolate in the morning (um, we want that breakfast), we’re probably pretty ready to hate on him for the rest of the novel: Yes. It took four men, all four ablaze with gorgeous decoration, and the Chief of them unable to exist with fewer than two gold watches in his pocket, emulative of the noble and chaste fashion set by Monseigneur, to conduct the happy chocolate to Monseigneur's lips. (2.7.2) In some ways, that’s not a fair analysis. Charles Darnay is a monseigneur, if we get right down to it. But maybe the allegory becomes as important for the ways it doesn’t fit as for the ways it does. We’re ready to hate all aristocrats. They’re all bad. But that makes us… rather like Madame Defarge. Scary, huh?