Criminal Law Case Briefs

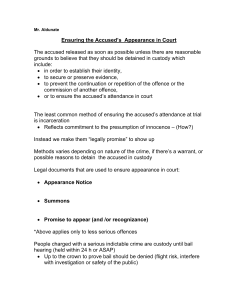

advertisement