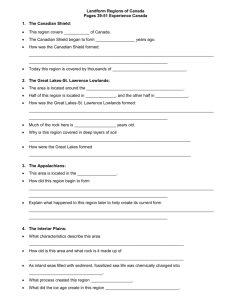

07 The Case of the Cordillera

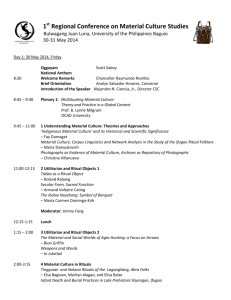

advertisement