Essay notes

advertisement

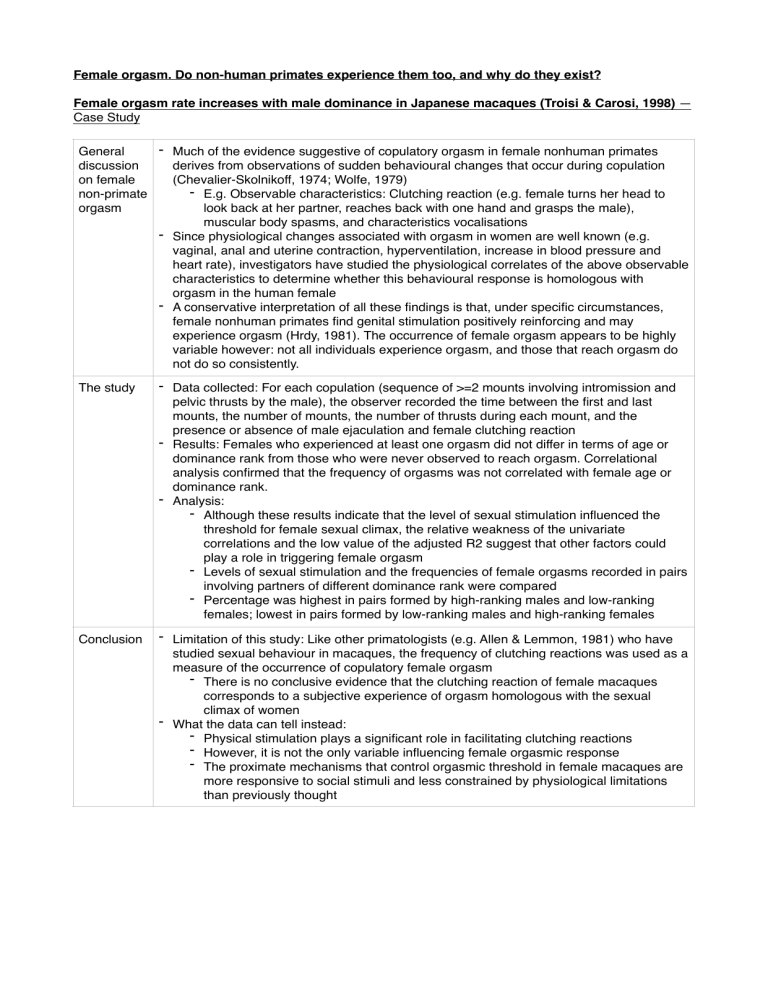

Female orgasm. Do non-human primates experience them too, and why do they exist? Female orgasm rate increases with male dominance in Japanese macaques (Troisi & Carosi, 1998) — Case Study General discussion on female non-primate orgasm - Much of the evidence suggestive of copulatory orgasm in female nonhuman primates - - The study - Data collected: For each copulation (sequence of >=2 mounts involving intromission and - - Conclusion derives from observations of sudden behavioural changes that occur during copulation (Chevalier-Skolnikoff, 1974; Wolfe, 1979) - E.g. Observable characteristics: Clutching reaction (e.g. female turns her head to look back at her partner, reaches back with one hand and grasps the male), muscular body spasms, and characteristics vocalisations Since physiological changes associated with orgasm in women are well known (e.g. vaginal, anal and uterine contraction, hyperventilation, increase in blood pressure and heart rate), investigators have studied the physiological correlates of the above observable characteristics to determine whether this behavioural response is homologous with orgasm in the human female A conservative interpretation of all these findings is that, under specific circumstances, female nonhuman primates find genital stimulation positively reinforcing and may experience orgasm (Hrdy, 1981). The occurrence of female orgasm appears to be highly variable however: not all individuals experience orgasm, and those that reach orgasm do not do so consistently. pelvic thrusts by the male), the observer recorded the time between the first and last mounts, the number of mounts, the number of thrusts during each mount, and the presence or absence of male ejaculation and female clutching reaction Results: Females who experienced at least one orgasm did not differ in terms of age or dominance rank from those who were never observed to reach orgasm. Correlational analysis confirmed that the frequency of orgasms was not correlated with female age or dominance rank. Analysis: - Although these results indicate that the level of sexual stimulation influenced the threshold for female sexual climax, the relative weakness of the univariate correlations and the low value of the adjusted R2 suggest that other factors could play a role in triggering female orgasm - Levels of sexual stimulation and the frequencies of female orgasms recorded in pairs involving partners of different dominance rank were compared - Percentage was highest in pairs formed by high-ranking males and low-ranking females; lowest in pairs formed by low-ranking males and high-ranking females - Limitation of this study: Like other primatologists (e.g. Allen & Lemmon, 1981) who have - studied sexual behaviour in macaques, the frequency of clutching reactions was used as a measure of the occurrence of copulatory female orgasm - There is no conclusive evidence that the clutching reaction of female macaques corresponds to a subjective experience of orgasm homologous with the sexual climax of women What the data can tell instead: - Physical stimulation plays a significant role in facilitating clutching reactions - However, it is not the only variable influencing female orgasmic response - The proximate mechanisms that control orgasmic threshold in female macaques are more responsive to social stimuli and less constrained by physiological limitations than previously thought Implications on functional analysis of female orgasm in non-human primates - The finding that male rank influences the probability of orgasmic response places in - - question the alternative hypothesis (Symons, 1979; Gould 1987) that female orgasm is an incidental by-product of male orgasm Our findings provide indirect evidence that primate female orgasm is an adaptation whose evolutionary function is selective mate choice - Human studies support the hypothesis that female orgasm has evolved as a female choice adaptation Compared with recent human studies, studies of proximate causation of female orgasm in nonhuman primates have focused on a limited number of variables with a major emphasis on physical stimulation - The present study shows the importance of one social factor: the dominance rank of the male partner [— relate to year 1 essay] - However, it is likely that males features other than rank may affect the probability of female orgasmic response. For example, macaque female sometimes show strong sexual preferences for unfamiliar, newly transferred males, and this can counteract preferences for high-ranking, resident males (Takahata, 1982). In addition, there is evidence that male aggression towards females, male affiliative relationships with infants, and male friendly behaviour towards females all affect females’ mating preferences (Smuts, 1986; Soltis et al., 1997). Orgasm in female primates (Allen & Lemmon, 1981) — Case Study & Reason Orgasm 1. 2. 3. 4. Changes in blood pressure, respiratory pattern and heart rate Changes in muscular tension (including vaginal and uterine contraction) Hormonal changes Emission of sound Argument 1 It is possible the orgasm exists in nonhuman female primates - Even with the paucity of information regarding the sexual responses of the nonhuman primates, it seems warranted to conclude that the capacity for orgasm in the female did not appear for the first time on this earth in our species, any more than did the propensity for continual sexual receptivity (Lemmon & Allen, 1978) - Case study - Allen (1977) manually stimulated the circumclitoral area and vagina of several chimpanzee females - Most permitted stimulation to continue to sexual arousal - One allowed stimulation to continue to orgasm on 10 separate occasions. The female invariably discontinued the stimulations by quadrupedally leaving the fence after her vaginal contractions had been palpated - A particular female (both clitoral and vaginal stimulation were being concurrently provided) reached back to grasp the thrusting hand of the experimenter and tried to force it more deeply into her vagina. On 2 occasions, this female’s infant was intensely interfering, during which times vaginal contractions were taking place. On neither of these occasions did the female terminate stimulation, whereas she did in similar instances of interference during earlier stages of her response. - Other sexual responses detected included transudate secretion, clitoral tumescence, vaginal thickening and expansion, hyperventilation, involuntary muscle tension, arm and leg spasms, clutching, facial expressions (e.g. low open grin, low closed grin, eversion of the lips, protrusion of the tongue), and a panting vocalisation. - Relatively few blatant emotional responses (e.g. vocalisation) associated with orgasm in women were manifested by the chimpanzee, even when intense vaginal contractions were being palpated Argument 2 What could possibly be the reason for its existence? (propose a theory for its evolutionary nature) - More than just to experience highly pleasurable sensations during sexual intercourse — it is intriguing that ecstatic sensations are felt during the contractions of the perivaginal musculature, which seems to effectively grip and massage the penis which may often result in ejaculation in a highly aroused male. It is their hypothesis that the orgasmic response in the anthropoid female (infraorder: Catarrhini), or perhaps in mammals generally, has evolved for the (adaptive role) purpose of stimulating the orgasmic response in the male - E.g. In human subjects: The female orgasm, as signalled by the woman, invariably preceded or accompanied the male orgasm (Bartlett, 1956) - E.g. Rhesus monkey: Frame-by-frame analysis of the film record revealed that the female’s reaction began before the male’s ejaculation —> there is a reason to think that the former might in some way be responsible for triggering the latter (Zumpe & Michael, 1968) - Another line of evidence: Ethological model of interindividual stimulus interaction - We now know that the female sex is not passive in sexual intercourse If that is assumed, then why do so many women fail to reach orgasm at all during coitus, or reach it only after a consideration duration, and the male still reaches orgasm without being stimulated by the female’s rhythmic vaginal contractions? - Incomplete expression of female sexual response: It is not suggested that this adaptive response has been selected to occur during every possible fertile copulation, but that as a component of reproductive effort it can function as a means of female choice after penetration has been achieved. There are, however, instances when vaginal contractions are not achieved by the female, even when sexual intercourse has been reported to be desirable. [LINK TO HRDY FROM BOSLEY] Reasons: - Male perspective — The ejaculatory threshold of the male fluctuates in relation to the number of orgasms he obtains over time… Therefore, if men today copulated more often, their ejaculatory thresholds would rise to a more species-typical level and orgasm would result from appropriate stimulation rather than from inappropriate sources, ie, from vaginal contractions instead of from vaginal corrugation or constriction - Female perspective — It has been well documented that many women cannot reach orgasm as quickly as can the average man because of psychological inhibition — can be attributed to the female’s naturally selected propensity to be relatively more discriminating in the partners she chooses for sexual intercourse than is the male — sex is not just a means of production - Female perspective — Inadequate control and development of the vaginal muscles Letter: Primate female orgasm (Phoebus, E. C., 1982) — Case Study Critique 1 Allen & Lemmon’s article: It suggests a proximal mechanism for the evolution of female orgasm in that it postulates a process which would optimise conceptive probabilities by encouraging spermatozoa to arrive in the right place at the proper time Heart rate (HR) in the unrestrained copulation of gang-caged rhesus females (Phoebus, 1977) SUPPORTS their hypothesis - HR peak rates were achieved before the final mount (on average about the fourth second - of the final mount) — this suggests that either the male somehow initially communicates that he is going to ejaculate on the current mount, or that the female indicates or initiates (by contractions) the finality of the mount. It does not seem likely that they achieve simultaneous orgasm independently Video records do show that the peak in female HR does anticipate the clutching reaction Critique 2 Allen & Lemmon's article: Only touched upon individual differences apparent among members of the same species including human It is his impression that an individual adult’s patten of sexual response (including the physiological) is much more similar to its former responses than it is to that of any other individual. This being true even with different partners and in spite of the apparent stereotypy of rhesus sexual behaviour. —> seem more important to the mechanism of mate selection then those involving fitness Limitations of current studies - Recent efforts to measure physiological changes in the sexual response of nonhuman primates have been rewarding in that they tend to refute the prevailing assumption that female orgasm is a phenomenon exclusive to the human female. The problem is that these studies, including my own, have been limited to artificial and contrived social situations making generalisation difficult. Monkey facts to human ideologies: Theorising female orgasm in human and nonhuman primates, 1967-1983 (Bosley, 2010) — Reason - Lloyd implies that controversy grew up around the evolution of female orgasm precisely because it had been observed initially in so few primates apart humans - Lloyd sees adaptationists and antiadaptationists - Hrdy saw anthropocentrists and antianthropocentrists (those who define female orgasm as a uniquely human attribute vs those who lobby to extend the orgasmic franchise to nonhuman primates) - Hrdy found significantly more women and feminists numbered among the latter group, while the former was composed of more “traditional” (male) scholars Implication - “how female monkeys and apes [got] their orgasms back, and what the story [has] to do - with the white, middle class branch of the Women’s Liberation Movement” (Haraway, 1989: 357) Defending Symons’s theory of female orgasm, Lloyd insists that “there is nothing inherently antifeminist about the thesis being explored here.” (2005, 141) For Lloyd, calling female orgasm a by-product — untoward semantics aside — is a salutary move for women, insofar as it divests their orgasms of reproductive significance and thereby (presumably) deprives men of a crucial ideological wedge for exerting control over women’s sexuality. Is female orgasm adaptive in an evolutionary sense, and if so, how? Morris Adaptationist & anthropocentrist — “Making sex sexier” (Morris, 1967: 65) Promotes monogamy - As humans developed a larger brain capacity and required a longer childhood, Morris - reasoned, greater parental investment was needed to ensure the survival of offspring —> the female was able to secure this investment from the male by, in effect, “making sex sexier”. To cement the “pair-bond” (38), it was imperative that she be available for sex whenever her partner might seek it. Orgasm facilitated this situation, acting as a behavioural reward to fashion the female into a willing and accommodating sexual partner. VS Hrdy: Because Morris understood the pair-bond as a uniquely human institution and because female orgasm had evolved to promote it, there was no room in his account for orgasm to occur in nonhuman primate females Symons Non-adaptationist — It is a byproduct of the selective advantage orgasm confers on males - By way of an infamous and widely cited analogy to male nipples, he argued that female - orgasm is a by-product of the selective advantage orgasm confers on males — that, although orgasm serves no adaptive function in females, it persists because both sexes develop from the same biopotential plan, and the clitoris is the female analogue of the penis. Consistent with this view, Symons acknowledged that the clitoris has no known function other than “to generate sensation — presumably pleasure — during copulation” (1979: 88) Because the occurrence of the female orgasm during reproductive sex is “sporadic”, it could not have enhanced reproductive fitness enough to promote direct selection for the trait (1979: 89) - On anthropocentrism - Symons, who denied that orgasm had ever conferred a selective advantage on - Hrdy females of any species, was not especially interested in resolving the matter of whether nonhuman primate females experience orgasm — his argument did not require that they do or they do not but only that they do not reliably during copulation Female orgasm was “most parsimoniously interpreted as a potential” possessed by all mammals but one that has been consciously cultivated in our own species alone (90) Adaptationist — Evolved as a behavioural reward Promote promiscuity - Female orgasm evolved as a behavioural reward — however, the behaviour rewarded was not commitment to a single male but rather copulating with as many males as possible — a promiscuous female would enjoy a selective advantage over a more sexually reserved one - 1. Consorting with many males would allow a female primate to assess the “capabilities” of each and to arrange to copulate with the fittest male available near the time of ovulation (1981: 150) - 2. By copulating with many males, a female confused the paternity of her offspring, thereby protecting them from infanticide and perhaps even encouraging multiple males to contribute to their care Is it a uniquely human phenomenon, or does it occur in nonhuman primates as well? Compare Symons and Morris - Symons: Orgasm in females is like unicycle riding in bears — it has no adaptive function in a natural habitat, but it may nonetheless emerge in the context of an adaptive way of life - Morris: Female orgasm was a component of a particular way of life, namely, the hunting way of life - Disagree: On the precise means by which female orgasm was woven into the system of adaptations constitutive of human sociality - Agree: Both arguments reduce to the ontological claim that female orgasm belongs to the domain of culture rather than nature - E.g. Symons likened women’s orgasms to “agriculture, the wheel, and indoor plumbing” (1979, 95) Symons and Morris VS Hrdy - “I disagree that ‘female orgasm is extremely unlikely to occur in nature’” (1979, 312) - Feminist anthropologist Zihlman noted approvingly that, for Hrdy, in contrast to her mostly male colleagues, “female sexual responses such as orgasms are not merely incidental or functional for male sexuality… [but] sexual enjoyment is a central part of female nature” (1985, 371) — Zihlman’s phrase is felicitous, for Hrdy’s primate females were a powerful proxy for female nature in a variety of registers Male-female, female-female, and male-male sexual behaviour in the stumptail monkey, with special attention to the female orgasm (Chevalier-Skolnikoff, 1974) — Case Study My critique: Use Troisi & Carosi to critique this (Under limitation section) Point - Females as well as males can experience orgasm, and the orgasmic patterns of the two - Evidence sexes are very similar — both showing body rigidity followed by muscular body spasms accompanied by the same facial expression and vocalisation An examination of stumptail females’ behaviour during coitus reveals two indications that orgasm does occur: the reaching-back and clutching behaviour, and the postejaculatory phase However, the unmistakable observation of orgasm in female stumptail monkeys during homosexual interactions and strong evidence for the occurrence of female orgasm in this species during heterosexual coitus, plus to coital behaviour of females in other macaques species, suggest that females of at least some of these species also experience Female homosexual behaviour — the encounters observed clearly show a naturally occurring complete orgasmic behavioural pattern for female stump tails - On 3 recorded occasions, the female mounter displayed all the behavioural manifestations of orgasm generally displayed by males: a pause followed by muscular body spasms accompanied by the characteristic frowning round-mouthed stare expression and the rhythmic expiration vocalisation - Besides being behaviourally homologous to the orgasmic behaviour of the male, the orgasmic response of the female stump tail monkey is essentially identical to the behaviour reported by Masters and Johnson (1966) in the human female. At orgasm, involuntary muscular tension occurs throughout the human female’s body: the muscles of the arms and legs contract spasmodically; if the hands are not already grasping something, they, as well as the feet, display involuntary grasping-like spasms; and the muscles of the face contract into a characteristic grimace. In addition, a number of other physiological changes (which could not be detected during this observational study) occur during orgasm: the uterus and the rectal and urethral sphincters contract, and respiration rate and blood pressure often increase.