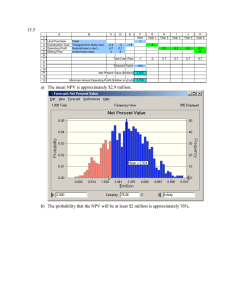

ch6

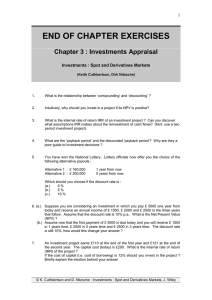

advertisement