Neoplasia: Benign & Malignant Tumors - Veterinary Pathology

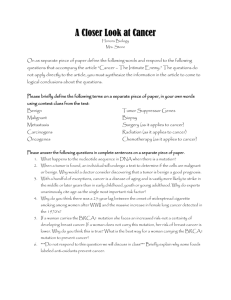

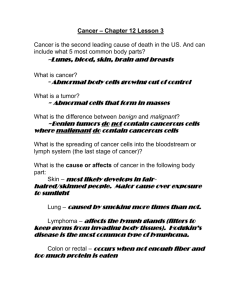

advertisement

Neoplasia University of Kufa Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Third year Pathology Dr. Hutheyfa Al Salih Neoplasia Nomenclature Neoplasia is the uncontrolled, disorderly proliferation of cells, resulting in a benign or Malignant growth known as a neoplasm (in ancient Greek, neo = new and plasma = creation). In common medical usage, a neoplasm often is referred to as a tumor, and the study of tumors is called oncology (from oncos, “tumor,” and logos, “study of”). the division of neoplasms into benign and malignant categories. All tumors have two basic components: (1) Neoplastic cells that constitute the tumor parenchyma (2) Reactive stroma made up of connective tissue, blood vessels, and variable numbers of cells of the adaptive and innate immune system. The classification of tumors and their biologic behavior are based primarily on the parenchymal component, but their growth and spread are critically dependent on their stroma. Benign tumor Benign tumor is microscopic and gross characteristics are considered, relatively innocent implying that it will remain localized and is amenable to local surgical removal. In general, benign tumors are designated by attaching the suffix -oma to the name of the cell type from which the tumor originates. Tumors of mesenchymal cells generally follow this rule. For example, a benign tumor arising in fibrous tissue is called a fibroma, whereas a benign cartilaginous tumor is a chondroma. The nomenclature of benign epithelial tumors is more complex; some are classified based on their cells of origin, others on microscopic pattern, and still others on their macroscopic architecture. 1 Neoplasia Adenoma is applied to benign epithelial neoplasms derived from glands, although they may or may not form glandular structures. Benign epithelial neoplasms producing microscopically or macroscopically visible fingerlike or warty projections from epithelial surfaces are referred to as papillomas. Those that form large cystic masses, such as in the ovary, are referred to as cystadenomas. When a neoplasm benign or malignant produces a macroscopically visible projection above a mucosal surface and projects, for example, into the gastric or colonic lumen, it is termed a polyp. Malignant Tumors Malignant tumors are collectively referred to as cancers. Malignant tumors can invade and destroy adjacent structures and spread to distant sites (metastasize) to cause death. The nomenclature of malignant tumors essentially follows the same schema used for benign neoplasms, with certain additions. Malignant tumors arising in solid mesenchymal tissues are usually called sarcomas (Greek sar- fleshy; e.g., fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma). Those arising from blood-forming cells are designated leukemia (literally, white blood) or lymphomas (tumors of lymphocytes or their precursors). Malignant neoplasms of epithelial cell origin, derived from any of the three germ layers, are called carcinomas. Thus, cancers arising in the ectodermally derived epidermis, the esodermally derived renal tubules, and the endodermally derived lining of the gastrointestinal tract are all termed carcinomas. Carcinomas may be further qualified. Squamous cell carcinoma denotes a cancer in which the tumor cells resemble stratified squamous epithelium, and adenocarcinoma denotes a lesion in which the neoplastic epithelial cells grow in a glandular pattern. Sometimes the tissue or organ of origin can be identified and is added as a descriptor, as in renal cell adenocarcinoma or bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. 2 Neoplasia Characteristics of benign and malignant neoplasms I. Differentiation and Anaplasia Differentiation refers to the extent to which neoplasms resemble their parenchymal cells of origin, both morphologically and functionally; lack of differentiation is called anaplasia. Benign neoplasms are composed of well-differentiated cells that closely resemble their normal counterparts. By contrast, while malignant neoplasms exhibit a wide range of parenchymal cell differentiation, most exhibit morphologic changes that resemble their malignant nature. Tumors composed of undifferentiated cells are said to be anaplastic, a feature that is a reliable indicator of malignancy. Anaplastic cells morphologic features: 1. Pleomorphism Variation in size and shape). Thus, cells within the same tumor are not uniform, but range from small cells with an undifferentiated appearance, to tumor giant cells many times larger than their neighbors. 2. Nuclear abnormalities Consisting of extreme hyper-chromatism (dark-staining), variation in nuclear size and shape, or unusually prominent single or multiple nucleoli. Enlargement of nuclei may result in an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. 3. Tumor giant cells formation These are considerably larger than neighboring cells and may possess either one enormous nucleus or several nuclei. 4. Atypical mitoses Mitosis may be numerous. Anarchic multiple spindles may produce tripolar or quadripolar mitotic figures. 5. Loss of polarity Anaplastic cells lack recognizable patterns of orientation to one another. Such cells may grow in sheets, with total loss of communal structures, such as glands or stratified squamous architecture. 3 Neoplasia II. Rate of growth Most benign tumors grow slowly, and most cancers grow much faster, eventually spreading locally and to distant sites (metastasizing) and causing death. The rate of growth of malignant tumors usually correlates inversely with their level of differentiation. In other words, poorly differentiated tumors tend to grow more rapidly than do well-differentiated tumors. III. Local invasion The growth of malignant tumors is accompanied by progressive infiltration, invasion, and destruction of the surrounding tissue, Nearly all benign tumors grow as cohesive expansile masses that remain localized to their site of origin and lack the capacity to infiltrate, invade, or metastasize to distant sites. Because benign tumors grow and expand slowly, they usually develop a rim of compressed fibrous tissue called a capsule that separates them from the host tissue. IV. Metastasis Metastasis is defined by the spread of a tumor to sites that are physically discontinuous with the primary tumor, and unequivocally marks a tumor as malignant, as by definition benign neoplasms do not metastasize. The invasiveness of cancers permits them to penetrate into blood vessels, lymphatics, and body cavities, providing the opportunity for spread. All malignant tumors can metastasize, but some do so very infrequently. The development of metastases, invasiveness is the feature that most reliably distinguishes cancers from benign tumors. Pathways of spread 1. Seeding of body cavities and surfaces Seeding of body cavities and surfaces may occur whenever a malignant neoplasm penetrates into a natural “open field” lacking physical barriers. Most often involved 4 Neoplasia is the peritoneal cavity, but any other cavity pleural, pericardial, subarachnoid, and joint spaces may be affected. 2. Lymphatic Spread Transport through lymphatics is the most common pathway for the initial dissemination of carcinomas Sentinel lymph node is the first regional lymph node that receives lymph flow from a primary tumor. It can be identified by injection of blue dyes or radiolabeled tracers near the primary tumor. Biopsy of sentinel lymph nodes allows determination of the extent of spread of tumor. 3. Hematogenous Spread Hematogenous spread is typical of sarcomas but is also seen with carcinomas. Arteries, their thicker walls, are less readily penetrated than are veins. 5