Reaching for Zero: A Citizens Plan

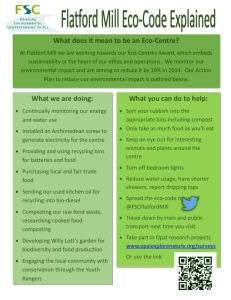

advertisement