Summative Evaluation of Canada`s Afghanistan Development

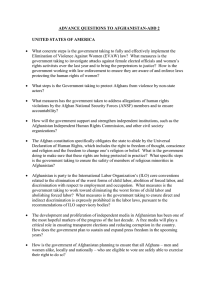

advertisement