Joint Strategic Needs Assessment - Solihull Metropolitan Borough

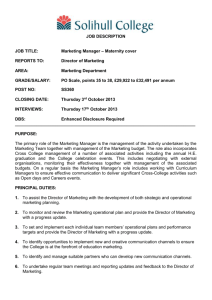

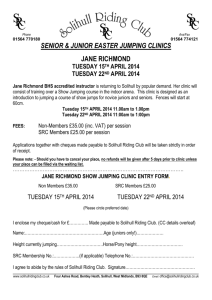

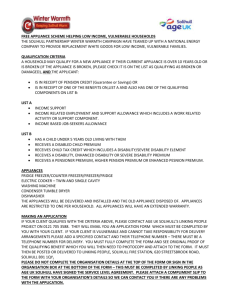

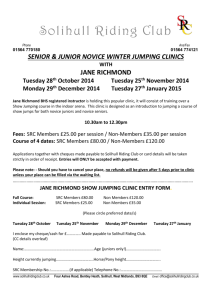

advertisement