Current Concepts Review - Corrosion of Metal

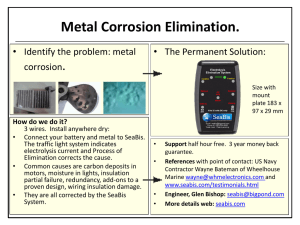

advertisement