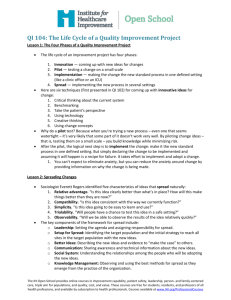

Course Summary - Institute for Healthcare Improvement

advertisement