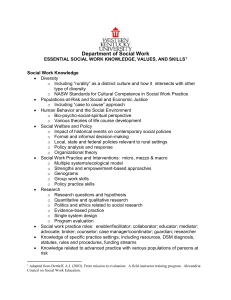

The Development of Cultural Competence in Social Work

advertisement