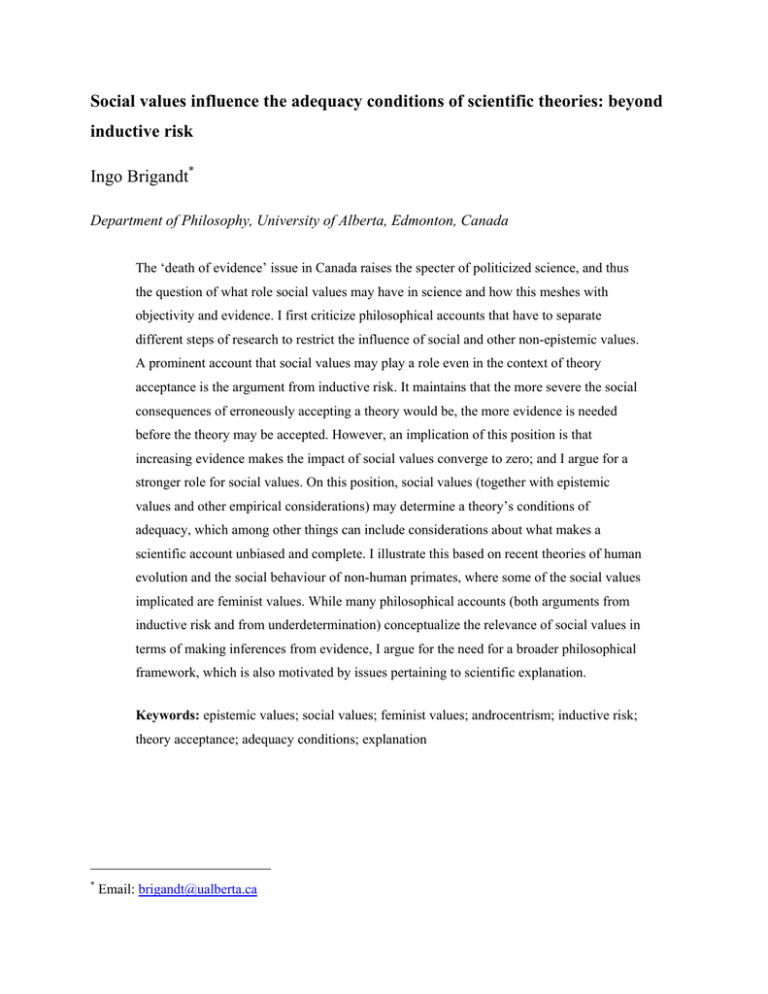

Social values influence the adequacy conditions of scientific theories

advertisement