New York Nonprofits in the Aftermath of FEGS

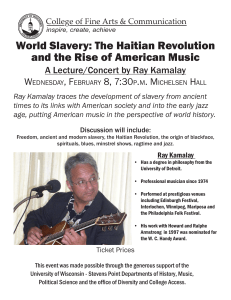

advertisement