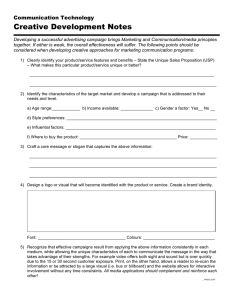

Creating an Energy Awareness Campaign

advertisement