MS Dissertation Human Resource Management

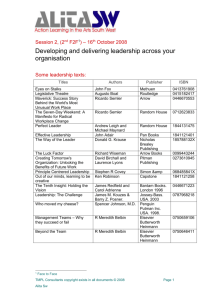

advertisement