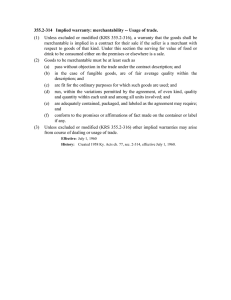

Some Aspects of Implied Warranties in the Supreme Court of Missouri

advertisement