Fire engineers worldwide use different codes and approaches when

Global voices

Fire engineers worldwide use different codes and approaches when designing safe and efficient buildings.

Here, Simon Goodhead compares the philosophies and practices in the USA and New Zealand

T

HE END result of fire engineered approaches in the built environment is globally consistent

– to protect people in and around buildings from fire – but the means by which fire engineers achieve this varies widely.

Most authorities (national, regional, local, etc) have developed legislation defining the goals and objectives for life safety in buildings, supported by standards, recommended practices and guidance.

The approaches set out in these documents world- wide enable varied routes to achieve similar goals.

To elaborate on this simple assertion, this article hears from two leading fire engineers from different parts of the world, who discuss the nuances of a concept design stage building. Each has identified their own approaches to a concept building, based on standards, recommended practices, guidance and codes enforced in their area, as well as considerations like the use of active systems, the evacuation strategy, and where value can be added for the owner.

The building is 60 storeys tall with a large podium shopping/entertainment plaza, apartment levels and a five-star hotel. For this exercise, it has been named

‘The Monarch Center’ (see box over page) .

Ben Hume, associate fire engineer at Beca New

Zealand, is using Queen Street, Auckland, New Zealand, as the hypothesised location. James Lugar, senior consultant at US consultancy Rolf Jensen & Associates,

Inc., is assuming the building is on Queen Street,

Alexandria, in the US state of Virginia.

The following questions help show the inherent differences, similarities and nuances of the two regions when it comes to the fire engineered design of the building.

www.frmjournal.com

October 2012 9

.c

lia om to

Fo

- es ag im ss le

P

© ay

Fire engineering

Concept building

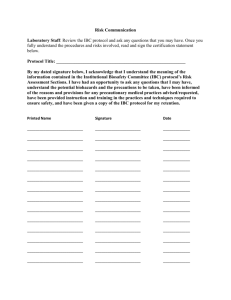

THE 60-STOREY Monarch Center – the concept building for this discussion – rises over 268m.

From the ground floor up, it features a large shopping and entertainment plaza, with a retail mall in excess of 120,000m 2 plus cinema and restaurants.

Above this is 28,600m 2 of office space across ten levels, and 21 levels of hip and accessible apartments, ranging in size from 80m 2 to 180m 2 .

Topping the structure is a 19-level five-star hotel. This features 333 rooms, each with 63m 2 of accommodation, a 2,000m 2 ballroom, and conferencing, leisure and entertainment facilities, including a spa, gym, outdoor swimming pool and cafés/restaurants

Images and building summary courtesy of Smallwood,

Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart & Associates, Inc.

What is the legislation you would use to design the fire safety aspects of the building? What design guide will you use to meet that legislation?

Ben Hume (B): Compliance must be with the New

Zealand Building Act. The Building Code then states key items that must be achieved, but this can be done by a number of methods.

There are some upcoming changes to the way

New Zealand approaches fire engineering. Currently, we use the Acceptable Solutions as one method of meeting the Building Code – this is similar to

Approved Document B in England and Wales – by providing simplified fire engineering solutions. Based on the building’s size, a combination of the Acceptable

Solutions and alternate design following the International Fire Engineering Guidelines (IFEG) would most likely be used.

However, from April 2013, the New Zealand

Building Code will be updated to state performance requirements such as tenability limits (essentially setting these in stone). In addition, complex buildings such as the Monarch Center cannot be based on the post-April 2013 Acceptable Solutions. Instead, the approach must be based on Verification Method 2:

Framework for Fire Safety Design (C/VM2) – a way of achieving compliance with the Building Code through formalising the fire assessment process.

C/VM2 provides ten prescriptive design fires that must be considered and modelled where necessary, and states parameters such as travel speeds, design fires, fire inputs, radiation limits, external fire spread and structural assessment techniques. The designer selects the fire locations and conducts the assessment based on these fixed inputs.

Ultimately, for occupant evacuation, the intent is to define ASET/RSET for multiple fire scenarios through the occupancy.

This more prescriptive approach means there is no ability to engineer certain aspects, such as fire sizes and tenability limits. So, in some instances where the reality would mean a low fuel load, the fires are still prescribed and the tenability limits must be met.

For this building, the analysis would be completed for each occupancy type.

James Lugar (J): The US is vastly different. Here, building designs are typically based on the Inter- national Building Code (IBC), which makes building design more prescriptive than performance based from a fire safety perspective.

The adoption of the IBC is based on the juris- diction and may include amendments on a federal, state, county or city basis.

There are also National Fire Protection Association

(NFPA) codes and standards, typically relied upon for specific system design. In addition, NFPA 101: Life

Safety Code is often used to substitute for the means of escape provisions in the IBC.

10 October 2012 www.frmjournal.com

Fire engineering

For the hypothetical building located in Alexandria,

Virginia, the IBC (2009 edition) is used. However, I’ve considered the building using the latest 2012 edition, which is very similar.

The IBC provides minimum life safety require- ments. In many instances, the document prescribes a one-size-fits-all solution. If there is a particular item that would create a hazard or is not constructible, the code has provisions for alternative methods of design.

It allows performance-based design if the intent can be demonstrated to be met and the level of safety compared to the prescriptive method is not lost.

However, performance-based designs are not often used in most jurisdictions.

From the developer/owner’s perspective, the prescriptive solution has been adopted for such a long period that construction methods and materials are lower cost, based on the prescriptive design. Where the performance-based design results in cost savings or increased value to the developer, it becomes an attractive option.

Do the codes consider property protection?

B: The New Zealand Building Act is based primarily around life safety. There are provisions to protect neighbouring buildings from fire spread. There is also

The Fire Service Act, which charges the fire service to protect life and, to an extent, property. C/VM2 has a specific scenario for fire service protection.

J: The IBC is mostly focused on life safety. Its stated intention is to protect life and property from fire, but it does not try to claim provision for resilience of a building after a defined period of time. For example, the intent may be to maintain stability for a minimum two-hour period in line with the construction type of the building. The defined fire resistance is based on comparative testing.

When reviewing the Monarch Center, what are the first items to consider?

B: I would look at the occupancy type; occupancy numbers; risk groups (a new definition in C/VM2 related to the occupancy type and the hazards within the area under consideration); height; and complex requirements of the building (such as an atrium).

These last two points impact directly on the requirement to use C/VM2 or an alternate design.

J: I would look at the site in terms of the exposure of this building to and from other buildings, the fire department access, and whether occupants can safely escape from the building.

Using the IBC, the construction type of the building is based on the occupancy type(s) and the height and area of each floor. In addition, by including proper sprinkler zoning, certain reductions in the fire resistance can be applied for some high- rise buildings.

Both the US and New Zealand codes would consider the six-storey shopping and entertainment plaza an atrium, and CFD modelling would be used to help determine tenability and smoke control provisions www.frmjournal.com

October 2012 11

Fire engineering

In terms of the vertical openings within the building, I would determine the appropriate classifications and requirements for smoke control systems if considered an atrium. I would question what the floorplans look like and would review the means of escape, separation of the exits, travel distances and common paths of travel. I would also look at what sprinklers, fire alarm systems, etc, would be needed.

In the UK, BS 5588-1 would apply to the residential apartment level. In some instances, a single stair would be permissible. If the building were re-stacked, could a single stair be used for the residential levels?

B: In theory, yes. The engineer would have to work through C/VM2 and determine, based on calculation, whether the performance criteria could be met.

J: I doubt a single stair would be possible using the

IBC. The approach is based on alerting everyone and evacuating using a minimum of two exit enclosures.

Defend in place strategies are only accepted where occupants are incapable of self-preservation. These would be two tough items to try and change and to demonstrate that an alternative is as safe as the code.

What would be the primary consideration for warning occupants of a fire? What do you see as being the sequence of events, from a fire starting to occupants being warned?

B: In a building this large, there would be sprinklers, smoke detection and pull points. Alerting would be through voice sounders. The requirement for visible warning for hearing-impaired employees and the use of strobes has been removed from the new design guidelines.

Would any of those means of detection affect the total travel of the number of occupants that can use the escape route?

B: If you use the prescriptive method, the allowable travel distance can be doubled if sprinklers or smoke detection are present. C/VM2 bases the pre- movement time on the detection time; as such, smoke detection can offer a significant advantage and allow for a longer period (and travel distance) for evacuation.

J: The primary means of detection would be through sprinkler water flow. The US codes consider sprinklers as being equivalent to heat detection as they are

J: Yes. Sprinkler protection allows for an increase in travel distance and common path of travel. The total travel distance is based on the occupancy type within the space. Smoke detection is

A single stair for the residential apartment levels might be allowed

not directly recognised in the

IBC as a trade-off for increasing travel distances. However, with a performance-based approach, the

with C/VM2 but not with the IBC

engineer can apply the smoke detection response time as compared to sprinklers, so premovement time can start sooner after fire initiation. located every 4.5m or so. Smoke detection would only be located in elevator lobbies, electrical rooms, and specific areas such as atriums.

Minimum audibility would be required to be met throughout using the Temporal Pattern 3 with voice messaging in-between the temporal pattern.

In addition, strobes would be required in any common and public use area.

Given the size of the Monarch Center, describe the egress philosophy for the building

B: The egress philosophy would be developed to some extent through the fire engineering brief process from the IFEG and would likely result in a staged evacuation process.

12 October 2012 www.frmjournal.com

Fire engineering

J: In Alexandria, Virginia, we would use selective evacuation, with evacuation on the fire floor, the floor below, and one or two floors above. The fire alarm circuits would then be protected accordingly.

The common approach for a tall building is to pressurise the stairwell. Lobbies could be used, but they take up space that can increase the building efficiency, so stairs accessed off the floor are preferred.

Elevators have started to gain acceptance and are specifically called for in the high-rise sections of the

IBC. There is a requirement to have elevator lobbies unless elevator pressurisation is provided, except that approach is difficult to achieve from a construct- ability standpoint. The IBC would require either an additional stair enclosure or an egress elevator, in addition to the calculated number of required stairs.

How would you determine the fire-resistance period of the building?

B: C/VM2 provides the inputs to calculate the required fire-resistance rating. These are mainly based on the

Eurocode time equivalence formula. New Zealand uses

Australian Standard, AS1530-4, for testing of products.

J: Testing in the US is based on the American Society for Testing and Materials E119 standard fire exposure, which uses a time temperature curve similar to the

ISO time temperature curve. It tests a set assembly in a restrained or unrestrained condition for a defined period of time, then applies a hose stream.

That assembly is assumed to be extrapolated through the entire structure and all the tests are comparative.

The fire service needs protection to fight a fire inside the building. How would that be achieved at the

Monarch Center?

B: In New Zealand, fire service lifts – standard lifts with minor modifications – are not frequently used.

C/VM2 requires water supply/delivery to be provided to all areas and that it can be shown that the fire service is in a comparatively safe environment relative to building design and conditions. The term

‘comparative’ has not yet been defined clearly.

The C/VM2 approach would lead the designer to a protected shaft.

J: The situation in the US is similar. The IBC requires an additional stair enclosure for buildings over 107m, in addition to the minimum required for escape.

This is to aid firefighter access and reduce issues associated with counterflow (occupants descending while fire crews ascend the same stair). www.frmjournal.com

October 2012 13

Fire engineering

In both approaches, sprinklers could be used to increase travel distances

Also, where floors are over 40m above grade, fire service access elevators are required to open into a lobby shared with a stair. The 2012 IBC requires two fire service elevators. There is not a requirement for the lobby to be ventilated, but the stair must be a smoke protected enclosure with pressurisation.

There are floor openings at every floor of the six- storey shopping mall. How would you approach that floor opening in your region?

B: New Zealand would consider it an atrium. A smoke control system would be required, comprising smoke exhaust, physical separation or a combination of both. Smoke modelling would be used to determine tenability, and an ASET/RSET calculation made.

C/VM2 would provide fixed fire sizes and reaction times of occupants. Computational fluid dynamics

(CFD) and zone models could be used.

The Fire Sector Summit offe debate on the opportunities iscussion and

and challenges

•

•

•

The event offers:

• strategic issues g key

• by John Humphrys from the sector excellent networking opportunities supporting exhibition packages

For more information and t tel: www.thefpa.co.uk/f

+44 (0)1608 812500 or o view the latest programme email: iresectorsummit training@thefpa.co.uk

Organised by:

Supported by:

Platinum sponsor:

OCTOBER

2012

FRM_Oct12_Covers.indd 1

Management

Fire

Risk

To advertise in

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURN

FIRE RISK

DESIGN VISION

Advertising sales

25/09/2012 14:04

The Fire Protection Association

Tel: +44 (0)1608 812 504 email: advertising@thefpa.co.uk

J: The space would be considered an atrium, as defined by the IBC. In terms of the design, it would probably be mechanical smoke exhaust fans with natural make-up air and possibly some mechanical make-up air. The intent is to keep the smoke layer

1.8m above the highest walking surface for 1.5 times the expected egress time or 20 minutes.

The smoke layer height is calculated using a variety of methods. Depending on the complexity of the space, a CFD model would be used where the smoke layer interface is not clearly defined and then the failure criteria are typically based on tenability criteria. US fire engineers have flexibility in selecting fire sizes, reaction times, and other pertinent criteria found in accepted guide documents/research.

Based on your knowledge of the codes you have referenced, where would you see value being added?

B: C/VM2 is intended to allow the building to be designed based on the risk levels and requirements of occupants, while minimising risk and resistance within the design process. It offers a number of benefits but, due to its simplified approach, does limit some techniques. Only the next few years will tell.

J: There are a lot of areas where value can be added.

Due to the large number of requirements in the IBC, some items get misapplied. In these instances, value is found through knowing the intent of the code.

This can allow for alternatives to be determined at the early design stages. For example, working with the architect to ensure a reservoir is included at the top of the atrium may result in optimising the required smoke control system.

Based on what you have heard, what are your impressions of the code in the other region?

B: New Zealand is essentially a test bed for the C/VM2 approach of risk-based fire engineering through a semi-prescriptive method. The IBC is much more prescriptive, but does consider larger buildings based on historical examples.

They are different approaches, but the end design will be similar. The ultimate floorplan layout for the

Monarch Center is likely to be different as regards the numbers of stairs, evacuation lifts, or ventilation provisions, but means of escape, fire protection and some fire service access features will be comparable.

J: The New Zealand codes sound fascinating. I like the idea of having the flexibility to complete various approaches to the designs. US codes are much more prescriptive, while our performance-based approaches have fewer parameter guidelines than New Zealand

Simon Goodhead is operations manager of the

Atlanta office of Rolf Jensen & Associates, Inc.

14 October 2012 www.frmjournal.com