problems faced by urban reisdents in performing urban domestic

advertisement

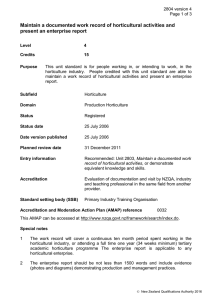

Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.26, No.1, 2010 103 PROBLEMS FACED BY URBAN REISDENTS IN PERFORMING URBAN DOMESTIC HORTICULTURE IN HAYATABAD TOWNSHIP: PESHAWAR AYESHA KHAN and UROOBA PERVAIZ Department of Agricultural Extension Education and Communication, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar - Pakistan. ABSTRACT In this research article an attempt is made to identify the kind and extent of horticultural activities, problems faced, availability of extension service and suggestions for the type of extension services needed in Hayatabad Township, Peshawar. A list of constructed houses of 4 phases i.e. I, II, III and IV of plot sizes 5 Marla, 10 Marla, 1 Kanal and 2 Kanal was obtained from Peshawar Development Authority (PDA). A stratified random sample of 50 owner-occupied houses was drawn with proportional allocation for 4 house sizes. An interview schedule was used to collect data during March- April 2008. The study found that all the respondents of the sampled households were literate. The sampled households were residing for an average of about 8 years. The horticultural activities comprised of lawns, flower plants, creepers, trees (Fruit and ornamental) and kitchen garden. The association between horticultural activities and plot size were significant for all horticultural activities except flower pots which was non-significant. The residents faced problems in the maintenance of activities and significant relation exist between problems and plot size for only lawns and kitchen garden. The households resolved their problems mostly through informal consultations. No formal system of extension services was available to cater for the domestic horticultural activities and solutions of problems. It is suggested that special write-ups, electronic media programmes (radio/TV) and constitution of forum of experts/professionals for consultation on problems and needs of domestic horticulture. Key Words: Urban domestic horticulture, problems of domestic horticulture, urban residents, extension services. Citation: Khan, A and U. Pervaiz. 2010. Problems faced by urban residents in performing urban domestic horticulture in Hayatabad township. Sarhad J. Agric. 26(1): 103-109. INTRODUCTION No developing country can afford to ignore the phenomenon of urbanization, which will be one of the strongest social forces in coming years, especially in developing countries. Within the next 20 years, more poor and undernourished people in developing countries will live in the cities than in rural areas. Today there are 35 cities whose population surpasses 5 million inhabitants and most of these are located in developing countries (Girardet, 1995). The urban population in developing countries is growing three times faster (3 % annually) than the rural population (less than 1 % annually). By the year 2030, the rural population will have grown by more than 235 million, but the urban population will have grown by 2.4 billion (United Nations, 1998). Proper vegetation in the urban localities particularly the residential houses has become of paramount importance on many counts- clean environment, aesthetic view, hobby and light physical exercise, kitchen garden for reduced dependence on rural products and getting fresh fruits and vegetables and is also a source of generating additional earnings. Almost all urban residents have some vegetation depending on available space in their house premises. The spacious houses have varied vegetation- lawns, flower plants, vegetables or kitchen garden, fruit and ornamental trees. Both the owner and Malis look after the vegetation. Urban Agriculture/Horticulture Horticulture is derived from two Latin words ‘hortus’ means ‘garden’ and ‘calere’ is ‘to cultivate’. Janick defines horticulture as “that branch of agriculture concerned with intensively cultivated plants used for food, for medicinal purposes or for aesthetic gratification”. Urban agriculture, defined as production in the home or plots in urban or peri-urban areas, is more widespread and important than generally thought. Some believe that it is not only a potentially significant source of income, food, energy, and micronutrients for family members, but that it can also benefit the environment by providing a way to reuse solid wastes and water. A number of studies now exist on the topic (Yeung, 1985; Sanyal, 1985; Rakodi, 1988; Lee-Smith et al. 1987; Freeman, 1991; Mvena, Lupanga, and Ayesha Khan et al. Problems faced by urban residents in performing urban domestic horticulture… 104 Mlozi, 1991; Sawio, 1993; Mbiba, 1995; Drakakis-Smith, 1991; Egziabher et al. 1994; Maxwell, 1995; Maxwell and Zziwa, 1992; UNDP, 1996). Smith et al. (1996) cite surveys that found that from 28% to 80 % of urban households in developing countries practice some form of urban agriculture. In Asia, commercial urban farming is more highly developed, especially with regard to vegetable and perishable-food production, but much of this production is also for home consumption (Prudencio-Bohrt, 1993). Still, most research on urban agriculture continues to reflect the conclusions of Sanyal (1985) that it is predominantly a strategy adopted by households whose monetary incomes are inadequate to purchase sufficient food (Maxwell 1995; Maxwell and Zziwa, 1992). Benefits of Urban Domestic Horticulture Floriculture, fruit and ornamental trees, vegetables or kitchen garden and grassy lawns are important activities in most urban residences. The houses undoubtedly give a pleasant and colourful look with freshness and fragrance in the air, clean and clear atmosphere and healthy environment and a sober soothing morning effect. All very essential for agile mental and robust physical health. Urban greening can reduce air pollutants to varying degrees. Air pollution is directly reduced when dust and smoke particles are trapped by the vegetation. In addition, plants absorb toxic gases, especially those from vehicle exhausts, which are a major component of urban smog (Nowak et al.1996). Akbari et al. (1992) found that tree shade could reduce the average air temperature in buildings by as much as 5 degree Celsius. Significance of Urban Agriculture As with any farm household, a household involved in urban agriculture is both producer and consumer. Urban agriculture also improves access to food by raising incomes if production is sold. The significance of urban agriculture can be measured in several ways: in terms of the proportion of the urban population engaged in the practice, in terms of income and employment, in terms of total production, and in terms of the impact on access to food and nutrition. In any case, the importance of urban agriculture varies with the city. Availability of land and agricultural inputs and municipal policies toward farming determine the extent of urban agriculture in most cases. The urban sector, residential localities in particular with their much needed vegetation, has received no attention under the prevailing agricultural extension system and services. Virtually these have been ignored and neglected in spite of their rapid growth- in number, population, territorial expansion, planned housing, centers of socio-economic development, trade and commerce and seats of public and private sector set-ups- federal, provincial, regional and district. Domestic horticulture is being practiced by every household in the space available in every township in Pakistan. However, little is known, at least in scientifically studied and documented form, about the state of the art of domestic horticulture being pursued. The residents do face problems about their horticultural pursuits, mostly for want of extension services. This research paper “Problems Faced by Urban Residents in Performing Domestic Horticulture in Hayatabad Township, Peshawar” is an attempt to explore the nature of domestic horticulture and problems faced. Objectives These include the following: i. The kind and extent of horticultural activities carried out in owner occupied houses. ii. The problems faced in carrying out the horticultural activities. iii. The availability of extension services/ personnel for problem solving. iv. The suggestions about the type of extension services required. MATERIALS AND METHODS The Hayatabad Township, Peshawar was selected as a case-study for this survey. In early 1970s Peshawar Development Authority (PDA) launched Hayatabad Township. It has seven Phases, out of these four were selected. The owner-occupied houses of 4 phases i.e. I, II, III and IV constituted the sample frame. Each phase has varied number of houses of 4 sizes- 5 Marla, 10 Marla, 1 Kanal and 2 Kanal. A list of constructed houses was obtained from PDA. The township had 11563 residential plots. Owners had constructed houses on 4165 plots (36%). A stratified random sample of 50 owner-occupied houses was drawn with proportional allocation for 4 sizes of houses. The formula of proportional allocation is: nh = n × Nh / N The distribution of sampled houses by size and phase is given in Table I. Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.26, No.1, 2010 Table I Phase I II III IV Total 105 Phase-wise number of total constructed/sampled houses by plot size Number of total constructed/sampled houses by size 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal 2 Kanal Total Sampled Total Sampled Total Sampled Total Sampled 553 7 435 5 200 2 164 2 147 2 136 2 443 5 252 3 501 6 353 4 276 3 2 285 3 203 3 214 3 1 1484 18 1127 14 1133 13 419 5 Total Total 1352 978 1132 701 4163 Sampled 16 12 13 9 50 An interview schedule was used as a research tool for the collection of required data. Data were collected during March - April 2008. Frequency distribution tables were made and Chi-Sq test was used to find association between different variables. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Family Education Urban localities in general have relatively more and higher literacy rate and education among both males and females. The literacy and education of the 50 surveyed households are presented by gender and by house size in Table II. Table II Educational status of sampled respondents by gender and house size Household Members by Gender and by House Size 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal 2 Kanal Family M F M F M F M F Education Matric 3 6 3 7 3 Higher 26 24 34 26 28 22 11 8 Students 33 21 11 13 12 10 4 3 Total 62 51 75 46 38 35 15 11 Note: M stands for Male and F for Female. Total (%) Sub-Total M F 6 16 99 80 60 47 165 143 22 (7) 179(58) 107(35) 308(100) The data presented in Table II show that all the respondents in the sampled households were literate. Out of these, 22 members of sampled households were educated up to matric, in which 6 were male and 16 were female. The respondents further reported that 179 members of sampled households were having higher degrees and 107 members were students. Years of residence The PDA staggered phase-wise allotment of plots in Hayatabad. Allottees, however, constructed houses in accordance with their convenience and need. The respondents, therefore, were residing in their houses for varying number of years (3-25). This information is shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 1 shows that about 44% of the total sampled households were residing in Hayatabad Township for up to 10 years. The remaining 56% of the respondents were residing for over 20 years. It is pertinent to note that only residents of 5 Marla were living in the township for more than 20 years. The average period of residing households was 8.03 years. The number of years of residence may have some reflection on the state of horticulture- normally the longer duration the better and more mature the plants. Horticultural Activities Every household has some horticulture, depending on the space spared after utilization for family living. Table III displays output for testing the significance of the relationship for size of plot and horticultural activities. It is clear from the output that relationship is statistically significant as (P< 0.01) and we reject the null hypothesis of no relationship. Only flower pots have non-significant relationship with plot size. The bigger the house size, the larger the available space and greater the scope for more varied horticulture- lawns, flower plants, fruit and ornamental trees and vegetables. Our results are in conformity with (Lalitha, 2004) who concluded that farm size was found significant in adoption and diffusion of agricultural technologies. Ayesha Khan et al. Problems faced by urban residents in performing urban domestic horticulture… 106 12 10 Frequency 8 6 plot size 4 5 marla 10 marla 2 1 kanal 0 2 kanals upto 10 years 11-20 years 21> years year of residence Fig. 1. Years of residence Table III Associations between horticultural activities and plot size Horticultural Activity Plot Size 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal No. % No. % No. % Lawn No 12 67 6 33 Yes 6 19 8 25 13 41 Flower beds No 11 73 3 20 1 7 Yes 7 20 11 31 12 34 Flower pots No 3 50 2 33 1 17 Yes 15 34 12 27 12 27 Creepers No 10 67 4 26 1 7 Yes 8 23 10 29 12 34 Trees (Fruit) No 12 71 5 29 Yes 6 18 9 27 13 40 Trees No 10 63 5 30 1 7 (Ornamental) Yes 8 23 9 27 12 35 Kitchen Garden No 18 46 12 31 8 20 2 18 5 46 Yes * N.S 2 Kanal No. % 5 15 5 15 5 12 5 14 5 15 5 15 1 3 4 36 Total Chi.Sq 18 32 15 35 6 44 15 35 17 33 16 34 39 11 17.7* 14.01* 1.35 N.S 10.83* 17.85* 10.56* 17.41* Significant at 1% Non-significant Horticultural Problems The households were consulted about the problems and difficulties faced in carrying out horticultural activities. The major problems reported were; watering, weeds, insects/pests, lack of sunshine, ants, poor soil and lack of guidance and know-how. The results regarding association between horticultural problems and size of plot are presented in Table IV. It is clear from the results that lawn and kitchen gardening has significant (P<0.01) relationship with plot size while flower plants and trees has non-significant relationship. Solution of problems The households were consulted as to how they solved their problems regarding horticultural activities. Their responses are given below in Table V. Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.26, No.1, 2010 107 Table IV Associations between horticultural problems and plot size Plot Size Horticultural Problems 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal No. % No. % No. % No 14 50 32 3 11 Lawn (Watering, Weeds, poor soil, insect/pests, sunshine) Yes 4 18 5 23 10 46 Flower plants (watering, dust, No 10 39 8 31 5 19 ants, diseases, sunshine, lack of Yes 8 33 6 25 6 33 guidance) Trees (watering, fruit flies and No 12 44 8 30 6 22 pests, thining, slow growth, not Yes 6 26 6 26 7 30 bearing fruit) Kitchen Garden (disease, No 18 43 13 31 9 21 insects/pests, sunshine, lack of Yes 1 13 4 50 know-how) * N.S Total Chi. Sq 28 22 26 24 10.09* 2 Kanal No. % 2 7 3 13 3 11 2 9 1.32 N.S 1 4 4 18 27 23 3.86 2 3 5 37 42 8 13.55* N.S Significant at 1% Non-significant Table V Problems solutions by sampled households Solution 5 Marla No effort made 2 Personal Know-how 7 Mali Takes Care 3 Professionals Consulted 4 Private Nurseries Approached - Number of houses by house size 10 Marla 1 Kanal 2 Kanal 2 4 8 10 4 4 6 5 5 7 3 2 3 Total 8 29 18 19 5 Table V shows that the members of 29 households personally tried to solve horticultural problems, while 19 sampled households consulted professionals, Malis/gardener took care of 18 houses, while 5 households approached private nurseries around the township to solve their horticulturist problems. Only 8 households made no effort to solve their problems. This situation calls for urban extension activities under the supervision of qualified staff (Ayesha, 2003). Extension personnel The 50 households were consulted about the state of extension personnel and services, providing the desired information regarding their domestic horticultural activities and operations and resolution of their difficulties. Their responses are given by size of houses in Table VI. Table VI Extension personnel of government, private sector organizations and NGOs in Hayatabad No. of Houses by Size Extension Personnel of 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal 2 Kanal Government Extension Services Private Sector Organizations 3 1 3 1 NGOs 1 Others i. Friends/Relatives/Neighbours 3 2 3 2 ii. Consultation with Professionals 1 1 1 1 iii. Mali contacted Experts 2 Total 10 4 7 4 Total 8 1 10 4 2 25 It is evident from Table VI that no extension personnel of government and non-government organizations provided horticultural information to the households. However, 8 households did get some information from personnel of private sector organizations particularly during their sale promotion campaigns about their products; one-fifth households consulted friends, neighbours, and relatives; and 4 households approached professionals when need arose; while 2 households left the matter to their Malis to make necessary contact with concerned quarters for remedial measures. Ayesha Khan et al. Problems faced by urban residents in performing urban domestic horticulture… 108 Ostensibly Hayatabad had extension personnel of neither public nor private sector organizations, nor even NGOs. Hence, horticultural needs of residents of Hayatabad were not formally tended to by professionals. Even the informal consultations among the friends, neighbours and relatives were rare. Hayatabad, thus, need urgently extension services for proper development of domestic horticultural pursuits and resolution of the problems residents faced in fructification of their efforts. Households suggestions for urban extension services Lastly, suggestions of the 50 households were solicited in respect of required Urban Extension Services. Varying number of households offered many suggestions, which are presented by house size in Table VII. Table VII Surveyed household’s suggestions for urban extension services No. of Houses by Size 5 Marla 10 Marla 1 Kanal SUGGESTIONS Specific Professional Services 5 7 5 Regular transmissions of Radio, T.V. 7 4 3 Specific Information and Know-how 6 4 3 Special Write-ups on Domestic Horticulture 3 5 4 Training, Seminar and Workshops 1 3 Seasonal Visits by Horticultural Experts 1 1 Hayatabad Advisory Body Films, Shows, Competitions for Motivation Total 21 22 19 Note: Totals do not tally due to multiple answers. Total 2 Kanal 4 2 2 3 1 1 1 14 21 16 15 15 4 3 1 1 76 Table VI lists suggestions of owner residents of Hayatabad Township, which focus on information, knowhow and advice on specific activities of urban domestic horticulture in the form of professional services, write-ups and regular Radio and T.V transmissions. These suggestions reflect the needs of the residents to equip themselves with the ken, the know-how and the do-how, for improvement of their horticulture. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS This case study of horticultural problems in owner-occupied houses of Hayatabad Township has come out with the following conclusions. Horticultural activities in Hayatabad comprised of lawns, floriculture- seasonal and perennial flower plants and creepers, fruit and ornamental trees and kitchen garden. The households faced problems in maintenance of lawns, floriculture, trees and vegetables and resorted to informal consultations with neighbours, relatives and professionals to solve their problems. The major problems reported were; watering, weeds, insects/pests, lack of sunshine, ants, poor soil and lack of guidance and know-how. It is also concluded, that Hayatabad residents had no formal system of extension services to cater for the domestic horticultural activities and solution of their problems. Well-organized formal extension education programmes and services are needed for the horticultural activities and operations being carried out by urban dwellers in their residences. Keeping in view the above discussion, the following recommendations are offered. i. Special write-ups, pamphlets and leaflets, booklets and instructional manuals should be prepared by the agricultural scientists, and agricultural extension services, to cater for the varied needs of the domestic horticulture. ii. The electronic media, Radio and TV should arrange specific education programmes for urban domestic horticulture. The transmission should suit timings of the urban residents, preferably in the morning for women and in the afternoon and evening for men. iii. Constitution of a forum of professionals, retired and on-job, for consultations on problems and needs, which arise more frequently and require urgent solutions for benefit of domestic horticulture. Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.26, No.1, 2010 109 REFERENCES Akbari, H., S. Davis, S. Dorsano, J. Haung and S. Winnett. 1992. Cooling our communities: A guidebook on tree planting and light colored surfacing. U.S. Envir. Prot. Agency, Washington, DC. Ayesha, K. 2002. A need for urban extension services: A case-study of Hayatabad Township. M. Sc (H) Thesis, Deptt. Agric. Ext. Edu. & Commun. NWFP Agric. Univ. Peshawar, Pakistan. Drakakis, S.D. 1991. Urban food distribution in Africa and Asia. Geographic. J. 157: 51–61. Egziabher, A., P.A. Memon, L. Mougeot, D. Lee-Smith, D. Maxwell and C. Sawio. 1994. Cities feeding people. Int'l Dev. Res. Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada FCND (Food Consumption and Nutrition Div.). 1998. Discussion Paper No. 51. Int'l Food Policy Res. Instt. Washington, D.C. USA. Freeman, D. 1991. A city of farmers: Informal urban agriculture in the open spaces of Nairobi, Kenya. McGill Univ. Press, Toronto, Canada. Girardet, H. 1995. The urban age: Sustainable cities in an urbanizing world. Websource: http://www.urbanage.net (accessed June, 2008). Janick, J. 1986. Horticulture Sci. 4th Ed. W.H. Freeman, New York. Lalitha, N. 2004. Diffusion of agricultural biotechnology andintellectual property rights: Emerging issues in India. Ecol. Econ. 49 (2): 187-192. Lee-Smith, D., M. Manundu, D. Lamba and K. Gathuru. 1987. Urban food production and the cooking fuel situation in Urban Kenya. Mazingira Instt. Nairobi. Maxwell, D. 1995. Alternative food security strategy: A household analysis of urban agriculture in Kampala. World Dev. 23 (10): 1669–1681. Maxwell, D. and S. Zziwa. 1992. Urban farming in Africa: The case of Kampala, Uganda. ACTS Press, Nairobi. Mbiba, B. 1995. Urban agriculture in Zimbabwe: The implications for urban management, urban economy, the environment, poverty and gender. Brookfield, Vt., U.S.A.: Ashgate Publish. Co. Mvena, Z.S.K., I.J. Lupanga and M.R. Mlozi. 1991. Urban agriculture in Tanzania: a study of six towns. Sokoine Univ. of Agric. Morogoro, Tanzania. Nowak, D.J., J.F. Dwyer and G. Childs. 1996. The benefits and costs of urban greening. Proc. urban greening seminar. Mexico City. Dec. 2-4. Ed. Krishnamurthy, L. and J.R. Nascimeto. Mexico: Universidad Autnoma de Chapingo. Prudencio, B.J. 1993. Urban agriculture research in Latin America: Record, capacities and opportunities. Cities Feeding People, Report No. 7. Int'l Dev. Res. Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Rakodi, C. 1988. Urban agriculture: Research questions and the Zambian evidence. J. Modern African Studies. 26 (3): 495–515. Sanyal, B. 1985. Urban agriculture: Who cultivates and why? Food & Nut. Bullet. 7 (3): 15–24. Sawio, C. 1993. Feeding the urban masses? Towards an understanding of the dynamics of urban agriculture in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Ph.D Dissert. Clark Univ. Worcester, Mass. USA. Smit, J., R. Anna and B. Janis. 1996. Urban agriculture: opportunity for sustainable cities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Report to the World Bank. UNDP (United Nations Dev. Program.). 1996. Urban agriculture: Food, jobs and sustainable cities. New York. United Nations. 1998. World urbanization prospects: The 1996 revision. New York. Yeung, Y. 1985. Urban agriculture in Asia. Tokyo: UN Univ. 44p.