Eaton paper- formatted

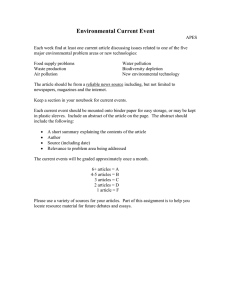

advertisement