R v Rahman - Publications.parliament.uk

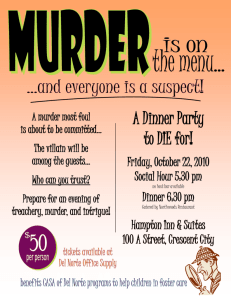

advertisement