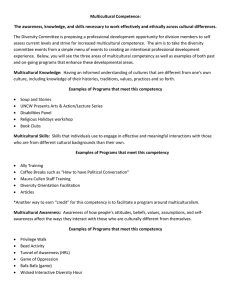

Assessing Multicultural Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills

advertisement