Irregular Heart Beats/Palpitations

advertisement

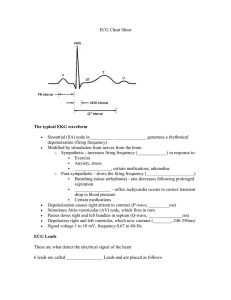

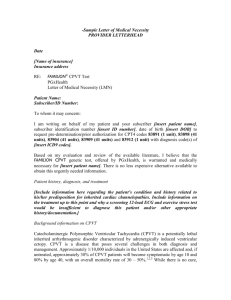

Irregular Heart Beats/Palpitations Anjan S Batra, M.D Director of Electrophysiology Associate Professor of Pediatrics University of California-Irvine CASE 1 • A 12 year old presents with a fast heart rate. He is otherwise asymptomatic. A wide complex rhythm h th iis noted t d att a rate t off 260 b bpm. Hi His bl blood d pressure is 92/50. The next best course of action would be: January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 1 A. B. C. D. E. Adenosine Sotalol Amiodarone Verapamil DC cardioversion SVT • In a hemodynamically stable patient, a supraventricular t i l ttachycardia h di with ith aberrant conduction is the most likely rhythm. • The best treatment for this patient would be administration of adenosine to terminate the tachycardia. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 2 CASE 2 An 8 year old presents with a fast heart rate and difficulty breathing. Blood pressure is stable. An ECG is obtained and shown below. There is no change g in the heart rate with adenosine. Your next course of action would be: A. DC cardioversion B. Sedation and atrial overdrive pacing C. Digoxin D. Beta blockers E. Verapamil January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 3 Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia • Originating from the left ventricle. • Adenosine is usually not effective in terminating the tachycardia. • Calcium channel blockers are very effective and hence this tachycardia is also referred to as verapamil sensitive ventricular tachycardia. • This is usually amenable to ablation. CASE 3: A 12 year old boy is undergoing a stress test for frequent ectopy at baseline. The echocardiogram at rest was normal. You notice the following rhythm at stage 5 of the standard Bruce protocol. The diagnosis is most consistent with: January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 4 A. A B. C. D. E. Brugada Syndrome CPVT Long QT type 3 Myocarditis Artifact Catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). • Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with ith exercise i • Brugada syndrome and long QT type3 – polymorphic ventricular tachycardia generally g y at rest or during g sleep. p • Myocarditis: decrease in cardiac function. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 5 CPVT • CPVT cannot be diagnosed on the basis of a resting ECG.1,2 • Exercise stress testing is an important part of a CPVT workup. – However, in as many as 20% of CPVT patients, formal exercise stress testing will not produce ventricular ectopy.1 • During exercise stress testing, bidirectional VT with a beat-to-beat 180degree rotation of the QRS complex is often observed.1 References: 1. Mohamed U, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Molecular and electrophysiological bases of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:791-797. 2. Kontula K, Laitinen PJ, Lehtonen A, Toivonen L, Viitasalo M, Swan H. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: recent mechanistic insights. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:379-387. Mutations in the Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor Gene (RYR2) Are the Major Cause of CPVT RYR2 • 12 60-65% of CPVT is caused by mutations of th cardiac the di ryanodine di receptor gene, which encodes a sarcoplasmic calcium ion channel.1,2 References: 1. Mohamed U, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Molecular and electrophysiological bases of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(7):791-797. 2. Hayashi M, Denjoy I, Extramiana F, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Arrhythmic Events in Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Circulation. 2009;119:2426-34. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 6 It Is Important to Differentiate Between CPVT and LQTS • CPVT is an LQTS mimicker.1 • As many as 30% of CPVT patients have been misdiagnosed as having “Long QT with normal QTc.”2,3 • Differentiating CPVT from LQTS is important for: - Developing a comprehensive treatment plan - Family-specific testing 13 References: 1. Choi G, Kopplin LJ, Tester DJ, et al. Spectrum and frequency of cardiac channel defects in swimming-triggered arrhythmia syndromes. Circulation. 2004;110:2119-2124. 2. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:69-74. 3. Napolitano C, Priori SG. Diagnosis and treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:675-678. Beta-blockers Do Not Provide Reliable Protection Against Cardiac Arrhythmias Related to CPVT • “However However, in light of incomplete protection afforded by beta-blockers in CPVT, its distinction from long-QT is clinically relevant.”1 • Nearly 50% of CPVT patients taking a betablocker continue experiencing cardiac arrhythmias and may require an ICD ICD.1 14 Reference: 1. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:69-74. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 7 Brugada Syndrome • The ECG of patients with BrS is characterized by – Coved- or saddleback-shaped ST-segment elevation in leads V1 through V31 – complete or incomplete right bundle-branch bundle branch block 1 – T-wave inversion • These ECG abnormalities may not be evident until unmasked by infusion of a sodium channel blocker (flecainide or procainamide).1 References: 1. Brugada R, Brugada P, Brugada J, Hong K. Brugada syndrome. Gene Reviews Web site. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=brugada. Accessed May 25, 2009. 2. Rossenbacker T and Priori SG. The Brugada Syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:163-70. BrS Typically Presents in Men 30-40 Years of Age • The most common presentation of BrS is a man 30-40 years of age with malignant arrhythmias and a history of syncope syncope.1,2 – Men are 8-10 times more likely than women to have the BrS phenotype.1,2 – There is no difference between men and women in the prevalence of gene mutations associated with BrS.1,2 16 • Men with an abnormal ECG and inducible ventricular arrhythmias have a poor prognosis.1,2 • If untreated, men with BrS have a 45% chance of having a cardiac event over the course of their life.1 References: 1. Brugada R, Brugada P, Brugada J, Hong K. Brugada syndrome. Gene Reviews Web site. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=brugada. Accessed May 25, 2009. 2. Rossenbacker T and Priori SG. The Brugada Syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:163-70. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 8 CASE 4 • A 14 year old patient with a history of WPW and SVT presents with this ECG. He is alert and hemodynamically stable. The MOST appropriate therapy is: A. Adenosine B. Lidocaine C. Observation D. DC cardioversion E. IV calcium channel blocker January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 9 WPW • Atrial fibrillation with rapid conduction over the th accessory pathway th results lt iin a rapid ventricular response. • At risk for ventricular fibrillation and compromised circulation. • Adenosine can also induce atrial fibrillation. • DC Cardioversion should be readily available. CASE 5 • A 12 year old boy comes to you with palpitations with exercise. He also complains of occasional chest pain with exercise. You obtain an ECG which is shown below. The next most obvious recommendation would be to: January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 10 • • • • • a. Perform an exercise stress test. b. Clear him for sports without any restrictions. c. Perform an echocardiogram. d. Perform a CXR. e. Perform a 30 day event monitor. Left ventricular hypertrophy with a strain pattern. • At risk for ventricular tachycardia and sudden dd cardiac di death d th with ith exercise i • Additional risk factors – family history of premature sudden death – extreme LV hypertrophy (> 30 mm) – NS ventricular tachycardia on Holter – unexplained (not neurally mediated) syncope January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 11 The Clinical Presentation of HCM • HCM is a progressive disease associated with varying degrees of LVH with no apparent cause.1 - 23 Thickening typically develops during late childhood and throughout adolescence.1 Reference: 1. Keren A, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the genetic determinants of clinical disease expression. Nature. 2008;5:158-168. Obstructive and Non-obstructive HCM LVH is usually maximal in the interventricular septum, but other localized variants have been documented.1 24 Reference: 1. Keren A, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the genetic determinants of clinical disease expression. Nature. 2008;5:158-168. January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 12 The Clinical Diagnosis of HCM Relies Primarily on Echocardiogram Echocardiogram can help determine: • Location and extent of hypertrophy • Systolic and diastolic function • The presence and degree of systolic anterior motion • The severity of subaortic and/or midventricular obstruction • Direction and degree of mitral regurgitation • The presence or absence of additional mitral valve abnormalities • Left atrial size 25 QUESTIONS January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 13 CASE 6 A 21 year old patient with classic Fontan presents with palpitations and fast heart rates for 3 days. ECG shows an unvarying heart rate of 140 bpm. He usually has a heart rate between 60 to 90 bpm. His blood pressure is stable. The following ECG is obtained. The next most appropriate pp p intervention would be: • • • • • a. b. c. d. e. Echocardiogram Digoxin Adenosine Sotalol Amiodarone January 14-15, 2011 SCA Conference 14