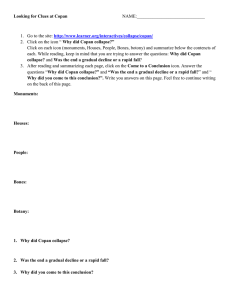

Intention and Design in Classic Maya Buildings at

advertisement