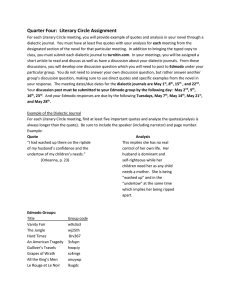

Rules and Standards

advertisement