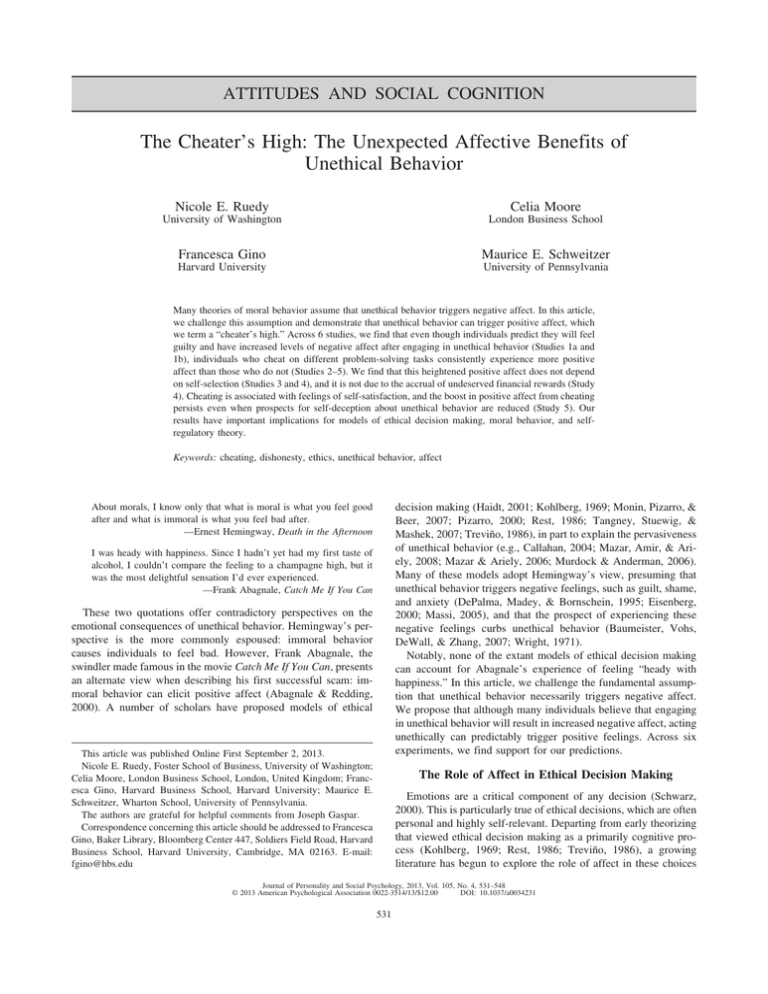

The Unexpected Affective Benefits of Unethical Behavior

advertisement