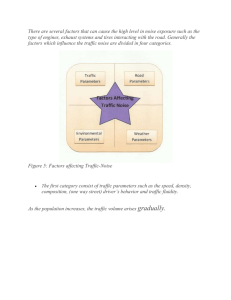

Part 3 - Noise management principles - EPA

advertisement