Professeurs et Recherche — HEC Lausanne

advertisement

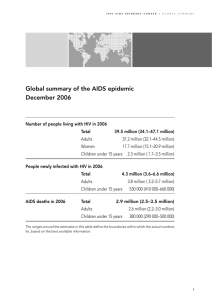

Journal of International Development J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) DOI: 10.1002/jid.801 HIV/AIDS AND DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA SIMON DIXON1, SCOTT McDONALD2* and JENNIFER ROBERTS1 1 Shef®eld Health Economics Group, University of Shef®eld, UK 2 Department of Economics, University of Shef®eld, UK 1 INTRODUCTION There were 3 million AIDS deaths in 1999 (UNAIDS, 2000), making HIV/AIDS the world's fourth biggest cause of death, after heart disease, strokes and acute lower respiratory infections. Over 70 per cent of the global total of 36.1 million people with HIV/AIDS live in Africa (see Table 1), and within Africa the incidence of HIV/AIDS cases is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, and especially those countries that form the so called `AIDS-belt' (see Figure 1). The worst affected countries in the world are found within this belt. In Botswana 35.8 per cent of the adult population are infected with HIV/ AIDS, in Zimbabwe this ®gure is 25.1 per cent, while South Africa, with a prevalence rate of 19.9 per cent has the largest number of persons living with HIV/AIDS (4.2 million) (UNAIDS, 2000). Whilst it is recognized that the rate of new infections in sub-Saharan Africa may be slowing down, and in fact fell from 4.0 million people in 1999 to 3.8 million in 2000, there is little cause for optimism. The sheer size of the disease pool, together with the disease's long incubation period, mean that HIV/AIDS will continue to have a major effect on the African people for decades to come. There is also the possibility that the disease may spread to some of the Western African countries that have so far been spared from the worst of the epidemic. If the epidemic starts to spread exponentially in these countries, as has happened throughout the AIDS-belt, the number of AIDS cases in Africa is likely to restart its upward climb. There must also be concern about the potential for the disease catching hold in Asia. While the prevalence rate in South and South-East Asia is only about 0.6 per cent, the absolute numbers of persons living with HIV/AIDS is large (5.6 million), and India with a prevalence rate of only 0.7 per cent is the country with the second largest number of victims (3.7 million). Although most of the headlines have been concerned with the health care implications and epidemiology of the disease, as demonstrated by the stark ®gures given above, there is a growing appreciation of the long-term impact of the epidemic on the social and Correspondence to: Dr. S. McDonald, Department of Economics, University of Shef®eld, 9 Mappin Street, Shef®eld, Tel: 0114 2223407. E-mail: smcdonald@shef®eld.ac.uk Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 382 S. Dixon et al. Table 1. Regional HIV/AIDS statistics, end of 2000 Sub-Saharan Africa North Africa and Middle East Rest of the world Total Adults and Children living with HIV/AIDS Adults and children newly infected with HIV Adults prevalence 25.3 million 400,000 10.4 million 36.1 million 3.8 million 80,000 1.4 million 5.3 million 8.8% 0.2% 0.4% 1.1% Source: UNAIDS, 2000. economic development of African countries. This issue is of fundamental importance to African economies as it is at the heart of determining the standard of living for their entire populations, not just those af¯icted by HIV/AIDS, and a crucial determinant of the ability of countries to support HIV/AIDS victims. Knowledge of the economic consequences is also necessary in order to understand the future development and well-being of these countries as they suffer the human and economic cost of the epidemic. Many case studies highlight the far-reaching impacts of the epidemic on African economies. A study in Zambia revealed that the annual average medical costs per employee for a sample of six ®rms increased more than three fold between 1993 and 1997 due to AIDS (UNAIDS, 2000). The cost to industry and agriculture is even higher when absenteeism due to AIDS related matters, such as caring for sick family members and funeral duties, is taken into account. In one study of an agricultural village in Tanzania it was found that if the household contained an AIDS patient 29 per cent of household labour supply was spent on AIDS-related matters (Tibaijuka, 1997). As well as the increased costs of production and reduced labour productivity illustrated by these two examples, the public sector labour market is also directly affected, limiting a country's ability to tackle the epidemic. In many countries, government and health service posts remain un®lled; Swaziland estimates that over the next 17 years, it will have to train more than twice the normal number of teachers in order to maintain current service levels (UNAIDS, 2000). While these studies illustrate the economic impact of HIV/AIDS, they do not form a coherent body of information that allows us to estimate the overall impact of the epidemic on the development of African economies, nor do they allow us to predict what future impacts lie in wait. The relative neglect of the epidemic until the last few years of the 20th century mean that knowledge about the multiple impacts of the epidemic are largely unknown and at best poorly understood. The selection of papers collected together here represent a small contribution to extending knowledge about the epidemic. The rest of this introduction is organized as follows. The next section comments brie¯y on the evidence about the prevalence of the virus. The third section provides a brief commentary on the possible impacts of the epidemic on economic development, which is followed by a section on policy choices and responses, before ending with some concluding comments. Throughout this introduction the discussion is related to the contents of the seven papers that make up this volume. 2 PREVALENCE A poor understanding of the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa up to the mid-1990s, led to prevalence estimates typically one seventh to one ®fth of those now produced by Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) HIV/AIDS and Development in Africa 383 Figure 1. HIV Prevalence in Africa (percentage of adults (15±49) infected end of 1999) UNAIDS. Since many attempts to assess the likely impact of HIV on development depend critically upon the estimated prevalence of the epidemic to parametize estimates of the implications for economic performance, health care expenditures, replacement rates for school teachers, etc., it is readily apparent that a quantitative understanding of the epidemic is essential. For instance despite the very large number of premature deaths from AIDS in recent years, it is only recently that estimates of life expectancy have begun to decline. For some countries in the AIDS-belt estimates are suggesting that life expectancy is now less than 40 years (US Bureau of Census, 1998). The ®rst paper in this collection, by Garnett, Grassley and Gregson, describes the key features of the HIV/AIDS epidemic that make it a particularly dif®cult challenge. They Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) 384 S. Dixon et al. draw attention to the long incubation period of the disease, which produces complacency in the behaviour of individuals and governments alike. Planning is made even more dif®cult by problems associated with monitoring and predicting disease prevalence. Taken together with other factors a situation has been created where HIV/AIDS is having a major impact on development through increased mortality and poverty, together with reduced economic productivity. Nevertheless Garnett et al., can highlight examples of success and hope; national programmes in Uganda and Thailand have helped reduce the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, while biomedical innovations hold out the hope for new treatments and vaccines. With an understanding of the key features described in this paper, the reader will have a fuller appreciation and understanding of the complexity of HIV/AIDS epidemic and the importance of the topics covered in the subsequent papers in this volume. 3 HIV/AIDS AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE While it is tempting to regard economic growth and development as synonymous, it is obviously a gross simpli®cation. Nevertheless economic performance, and particularly growth, does provide a useful, if crude, starting point for the assessment of development and the impact of HIV/AIDS on development. Much of the empirical work has used calibrated neo-classical growth models, wherein it is hypothesized that growth is primarily determined by the growth of the workforce, the productivity of the workforce and investment in future production. Early studies, e.g., Over (1992) for 10 African countries with the most advanced epidemics and Cuddington and Hancock (1994) for Malawi, concluded that the epidemic would have an appreciable impact on economic performance. A conclusion that similar recent studies, e.g., BIDPA (2000) for Botswana, endorse. However, the resultant estimates are highly sensitive to the parameterisation of the model. Estimates by the IMF (reported by Haacker, 2001) suggest that in the long run, i.e. by 2050, GDP per capita might increase by 10 per cent or more in the worst affected countries of Africa, but that capital out¯ows would reverse this conclusion so that GDP per capita would decline marginally. But there has been little in the way of econometric analyses of the epidemic. The second paper in this volume, by Dixon, McDonald and Roberts, reports an assessment of the macroeconomic consequences of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the context of a neo-classical model of economic growth. The motivation is that while the human and social costs of HIV/AIDS in Africa are devastating, any deterioration in economic performance is likely to compound those costs and render countries less able to cope with the epidemic. Using data from 41 African countries for the period 1960 to 1998, Dixon et al., estimate an augmented Solow model in which the growth of income per head is partly determined by health capital, where health capital, in turn, is partly determined by the prevalence of HIV/AIDS. The main ®nding is that HIV/AIDS prevalence has a pronounced impact on life expectancies, which suggests that the epidemic may now be entering the stage where the loss of life is starting to impact appreciably upon social and economic interactions. These results challenge those reported by Bloom and Mahal (1997), who estimated that the impact of AIDS across a world-wide sample of 51 countries showed a minimal impact on GDP per capita. Further sub-sample analyses indicate that for African countries where the prevalence of HIV is relatively low, the impact of the Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) HIV/AIDS and Development in Africa 385 epidemic conforms to `normal' economic expectations. However, when the prevalence of the epidemic is relatively high the macroeconomic impact of the epidemic is unclear. Growth models typically use aggregated data and thereby mask important information about the demographic and sectoral impacts of the epidemic. In particular the AIDS epidemic impacts disproportionately on young adults, thereby undermining the bene®ts of investment in education and training. The models also assume (implicitly) that all types of labour are perfect substitutes within the time period considered by the analyses, which may be true in the long run but within the time frame that policy makers must operate economies are characterised by imperfect substitutability. Consequently, reductions in labour productivity will differ between skill groups, and ®rms struggling to train replacement staff might heighten the impact of the epidemic. Especially if those sectors most affected are important to the economy, e.g., mineworkers in South Africa. Just as the differential impact of the epidemic on skills may vary across different sectors in the economy, differential effects between sectors can also impact differentially on the economy as a whole. Reductions in labour supply and productive ef®ciency will reduce both output and competitiveness. If labour shortages become particularly severe in critical sectors the macroeconomic effects are likely to be ampli®ed. Kambou et al. (1992) used a general equilibrium model to assess the impact of these concerns in the context of Cameroon. The results indicated that reductions in the availability of skilled labour are likely to have particularly severe impacts on economic performance. The third paper, by Arndt and Lewis, reports results from a dynamic general equilibrium model for South Africa that assesses the implications of the epidemic for macroeconomic, sectoral and unemployment effects. This type of model places a premium on information about the economic implications of the epidemic; among the (peculiar) bene®ts to come from this study are a realization of how little is really known about the epidemic. The analyses indicate labor demand will be depressed by the decline in the overall growth rate, a reduction in investment demand that will particularly reduce the demand for unskilled and semi-skilled workers, and that the AIDS induced morbidity effects will further depress demand for unskilled and semi-skilled workers. Rapid economic growth, especially in sectors that use skilled and semi-skilled labour intensively, which if combined with real wage moderation and/or cuts, should ameliorate some of the impact. This study reports negative impacts from the epidemic that are greater than those commonly produced by growth models, and moreover does so using a method that typically reports smaller effects than a priori reasoning might suggest. 4 PRIORITIES AND DIFFICULT CHOICES Economic models may be useful in assessing the impact of the AIDS epidemic, but they cannot, by themselves point to the policies that will minimize the reductions in economic growth and standard of living. The choice of policies is agonisingly dif®cult given the delicate state of many African economies. Treatment of HIV/AIDS is extremely expensive relative to other priorities, for example, the cost of one year's supply of AZT for one person in the US was over 1,000 times the annual per capita health care budget of Uganda in 1987. These treatment costs, which are based on dollar pricing, will move further out of reach if the weakening economies of the developing countries experience currency devaluation. Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) 386 S. Dixon et al. More generally, any attempt at a comprehensive prevention and treatment programme requires resources that most developing countries simply do not have. Comprehensive HIV prevention schemes require media campaigns, prostitute and school education, social marketing of condoms, blood safety and needle exchanges. Broomberg et al. (1996) estimated that provision of such schemes would require over US$2 billion annually for all developing countries, with annual per capita costs equivalent to US$0.72 for selected African countries. These estimates are based on limited data sources, and represent early estimates of the scale and cost of prevention strategies. However, even these estimates are far beyond actual expenditure; Tanzania and Uganda, for instance, currently spend less that 10 per cent of that required for the prevention package examined by Broomberg, implying that switching substantial funds toward HIV prevention is necessary. Information on the cost-effectiveness of different interventions are required so that the impact of prevention and treatment programmes can be maximised. Ainsworth and Teokul (2000) identify the piecemeal development of HIV programmes as a weakness in many countries. They criticize well-intentioned approaches that spread resources across dozens of different activities rather than focusing on providing a small set of the most costeffective studies on a national scale. The treatment of mother-to-child transmission, for example, is cited as a political rather than economic priority that may ` . . . have important bene®ts but virtually no effect on the course of an epidemic fuelled by sexual transmission' (Ainsworth and Teokul, 2000, p.56). Another politically expedient issue, which has served to divert attention away from the essential task of assessing the most cost-effective government responses, is the row surrounding the pricing of anti-retroviral therapy for patients with HIV/AIDS. There is growing public outrage concerning the pharmaceutical companies' policy toward the pricing of these therapies, which remain beyond the means of all African health systems. However, even if drug prices are slashed following the collapse in April 2001 of the case by the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers' Association of South Africa and 39 international drug makers against the government of South Africa, the use of these therapies will not necessarily be the most cost-effective approach to combating the epidemic. This is because the effective use of anti-retroviral therapies needs a well-developed and wellresourced medical infrastructure to facilitate the monitoring of the therapy. Without careful monitoring and high patient compliance, anti-retroviral therapy is not particularly effective and may even encourage the development of newer and more virulent strains of HIV. Consequently, the issue of drug pricing should not detract from ongoing research into the cost-effectiveness of other interventions. The remaining papers in this volume address some of the myriad of issues that are raised by the need to respond to the epidemic. The paper by Kumaranayake and Watts starts the process by considering the broad range of interventions that can be used to both prevent and treat HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Given the endemic nature of the epidemic there has been both a reallocation of resources towards HIV/AIDS and wide scale efforts at mobilizing additional resources. However, despite these efforts, priority setting among the various interventions remains a central issue, with broad debates about how resources should be allocated, and particular concerns about treatment and the availability of drugs. A fundamental problem in priority setting is the extremely limited evidence-base available to guide policy makers. The authors' stress that debates on priorities must consider the feasibility of alternative delivery mechanisms in different settings, and highlight the importance of investing in infrastructure and capacity to increase the scale of activity. In addition the mix of interventions will need to change over the course of the epidemic, with Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) HIV/AIDS and Development in Africa 387 priorities for interventions shifting between population sub-groups, and from more targeted to broader population-focused interventions, as the patterns of HIV incidence change over time. For many people one of the great sources of hope for development is education. But there is mounting evidence that maintaining the number of teachers will be increasingly dif®cult. Estimates by the IMF, reported by Haacker (2001), suggest that HIV/AIDS will appreciably increase the proportion school leavers that will need to be recruited into teaching if the current student±teacher ratios are to be maintained. But education is not only important for social and economic development; it may also be important to controlling the spread of the disease. The paper by Gregson, Waddell and Chandiwana reports a thorough review and investigation of the impact of school education on HIV prevalence. Many commentators have identi®ed a positive relationship between adult literacy and adult HIV prevalence and have discussed the implications of this for disease control. Gregson et al., replicate these simplistic analyses, but look deeper by analysing how this relationship varies between sub-groups of African countries. They forward the hypothesis that in the early stages of an epidemic, the spread of HIV is fastest in the bettereducated populations, due to their riskier behaviours, but once the epidemic has grown, and its presence is known to individuals, the better educated populations change their behaviour faster. This hypothesis is supported by a unique review and synthesis of the results of all the available longitudinal studies from Africa. The paper offers an insight into the complex social dynamics of HIV transmission, and is an important contribution to the speci®c topic of school education and HIV control. Undoubtedly government policies in Africa will need to change; but decision makers require information to guide the policy making process. Haddad and Gillespie address this issue in the context of policies relating to food security, nutrition, agriculture and the environment and how policies might be formulation to better meet the needs of the poor. They explore the linkages between poverty, nutritional status and the development of the disease with respect to the implications for the welfare of the poor, especially the large majority of people who live in poverty, who are resident in rural areas and who are dependent upon agriculture and natural resources to sustain their livelihoods. Their analysis emphasises policy choices that can mitigate the worst impact of the epidemic. In so doing the authors echo the arguments of Bonnel (2000), who argued the need for policies aimed at reducing income inequality, gender inequality and ethnic divisions. They conclude that there is greater need for community involvement and ownership of programmes; that existing rural and agricultural institutions should be used to disseminate information and services; that nutritional support, with two-stage targeting, has the potential to postpone the onset of full blown AIDS and prolong life; and that the multitude of information gaps are constraining effective mitigation policies. A recurrent theme of Haddad and Gillespie's paper is the shortage of `hard evidence' and how this inhibits the policy making process. Finally, Lamboray and Skevington address the issue of community involvement and the development of `AIDS competent' societies, by drawing upon the work of the World Health Organization's Quality of Life Assessment group. They stress the importance of empowering individuals and communities as a means of reducing the spread of the infection, developing appropriate and effective care and support mechanisms, and devising strategies that are supported by both local and regional communities. The approach stresses the importance of supporting bottom-up approaches to coping with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Hence the paper provides a powerful reminder of the fact that Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) 388 S. Dixon et al. governments cannot supply all the solutions to living with an epidemic, and that when formulating policy responses governments would be well advised to motivate collective behavioural responses that can help reduce the spread of the epidemic and mitigate the worst effects on those already infected. 5 CONCLUSION Governments in sub-Saharan Africa are confronted by increasingly dif®cult policy questions. Some government departments have been content to view the problems presented by HIV/AIDS as the responsibility of the department of health, or have tried to shape the problem as being caused by multi-national drug companies. This reluctance to plan an overall government response, combined with the fact that ®scal crises and structural adjustment programmes have already adversely affected health budgets, has probably contributed to the spread of HIV/AIDS. In future governments will have to make far-reaching and politically sensitive choices. For example, if the (economic) standard of living is considered important when planning government interventions, prevention programmes may have to be targeted at the most economically productive socio-economic groups. It may even become optimal to allow expensive anti-retroviral treatment for selected groups in speci®c industries, based on their contribution to economic output, in order to allow time for replacement labour to be trained The epidemic is clearly not simply a health problem. It may have potentially devastating economic and social consequences, and it is essential that more is discovered about the potential implications if individual governments and international agencies are to devise appropriate policy responses. The sub-Saharan Africa countries constitute the majority of the countries in the bottom third of the UNDP Human Development Index, hence those countries most affected by the epidemic are those least able to cope with it. Indeed it is heartening that some bodies are recognizing this: the International Development Committee of the UK Parliament has drawn attention to the ability of poor countries to fund AIDS expenditures and urged that as much as possible of the World Bank's programme for HIV/AIDS in Africa be in the form of grants as opposed to loans (House of Commons, 2001). REFERENCES Ainsworth M, Teokul W. 2000. `Breaking the silence: setting realistic priorities for AIDS control in less-developed countries'. Lancet 356: 55±60. Bonnel R. 2000. What makes an economy HIV-resistant? World Bank: Washington DC. Caldwell J.C. 1997. The impact of the African AIDS epidemic. Health Transition Review 7 (Supp. 2): 169±88. BIDPA. 2000. Macroeconomic Impact of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Botswana. BIDPA: Gaborone. Bloom DE, Mahal AS. 1997. Does the AIDS epidemic threaten economic growth? Journal of Econometrics 77, (105): p.105±124. Broomberg J, SoÈderlund N, Mills A. 1996. Economic analysis at the global level: a resource requirement model for HIV prevention in developing countries. Health Policy 38: 45±65. Cuddington JT, Hancock JD. 1994. Assessing the impact of AIDS on the growth path of the Malawian economy. Journal of Development Economics 43: 363±368. Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001) HIV/AIDS and Development in Africa 389 Haacker M. 2001. Crisis in Africa: The Economic Implications of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Centre Piece 6: 8±13. House of Commons. 2001. HIV/AIDS: The Impact on Social and Economic Development, Volume 1. Third Report of the International Development Committee. HC 354-1. London: HMSO. Kambou G, Devarajan S, Over M. 1992. The Economic Impact of AIDS in an African Country: Simulations with a Computable General Equilibrium Model of Cameroon. Journal of African Economies 1: 109±130. Over M. 1992. The macroeconomic impact of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank, Population and Human Resources Department: Washington DC. Tibaijuka AK. 1997. AIDS and economic welfare in peasant agriculture: case studies from Kagabiro Viallage, Kagera Region, Tanzania. World Development 25: 963±975. UNAIDS. 2000. AIDS Epidemic Update, UNAIDS: US Bureau of Census. 1998. Copyright # 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Int. Dev. 13, 381±389 (2001)

![Talking Global Health [PPT 1.64MB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015013625_1-6571182af875df13a85311f6a0fb019f-300x300.png)