S CI EN C E OF TH E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

a v a i l a b l e a t w w w. s c i e n c e d i r e c t . c o m

w w w. e l s e v i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / s c i t o t e n v

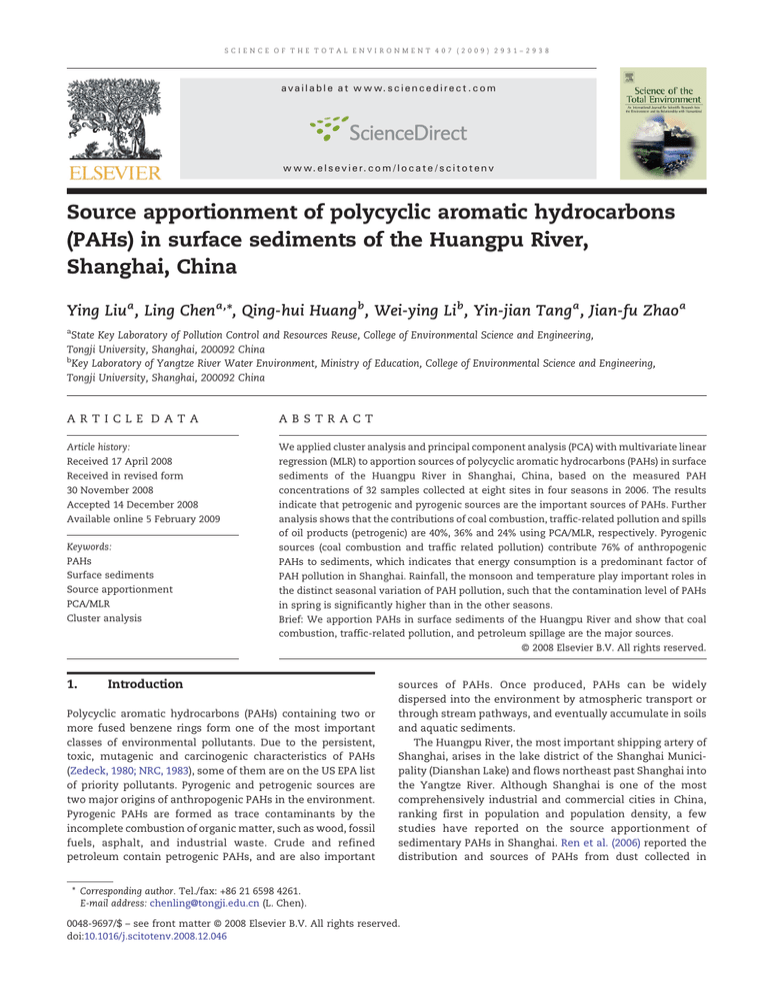

Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

(PAHs) in surface sediments of the Huangpu River,

Shanghai, China

Ying Liu a , Ling Chen a,⁎, Qing-hui Huang b , Wei-ying Li b , Yin-jian Tang a , Jian-fu Zhao a

a

State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resources Reuse, College of Environmental Science and Engineering,

Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092 China

b

Key Laboratory of Yangtze River Water Environment, Ministry of Education, College of Environmental Science and Engineering,

Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092 China

AR TIC LE D ATA

ABSTR ACT

Article history:

We applied cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) with multivariate linear

Received 17 April 2008

regression (MLR) to apportion sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface

Received in revised form

sediments of the Huangpu River in Shanghai, China, based on the measured PAH

30 November 2008

concentrations of 32 samples collected at eight sites in four seasons in 2006. The results

Accepted 14 December 2008

indicate that petrogenic and pyrogenic sources are the important sources of PAHs. Further

Available online 5 February 2009

analysis shows that the contributions of coal combustion, traffic-related pollution and spills

of oil products (petrogenic) are 40%, 36% and 24% using PCA/MLR, respectively. Pyrogenic

Keywords:

sources (coal combustion and traffic related pollution) contribute 76% of anthropogenic

PAHs

PAHs to sediments, which indicates that energy consumption is a predominant factor of

Surface sediments

PAH pollution in Shanghai. Rainfall, the monsoon and temperature play important roles in

Source apportionment

the distinct seasonal variation of PAH pollution, such that the contamination level of PAHs

PCA/MLR

in spring is significantly higher than in the other seasons.

Cluster analysis

Brief: We apportion PAHs in surface sediments of the Huangpu River and show that coal

combustion, traffic-related pollution, and petroleum spillage are the major sources.

© 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1.

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) containing two or

more fused benzene rings form one of the most important

classes of environmental pollutants. Due to the persistent,

toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic characteristics of PAHs

(Zedeck, 1980; NRC, 1983), some of them are on the US EPA list

of priority pollutants. Pyrogenic and petrogenic sources are

two major origins of anthropogenic PAHs in the environment.

Pyrogenic PAHs are formed as trace contaminants by the

incomplete combustion of organic matter, such as wood, fossil

fuels, asphalt, and industrial waste. Crude and refined

petroleum contain petrogenic PAHs, and are also important

sources of PAHs. Once produced, PAHs can be widely

dispersed into the environment by atmospheric transport or

through stream pathways, and eventually accumulate in soils

and aquatic sediments.

The Huangpu River, the most important shipping artery of

Shanghai, arises in the lake district of the Shanghai Municipality (Dianshan Lake) and flows northeast past Shanghai into

the Yangtze River. Although Shanghai is one of the most

comprehensively industrial and commercial cities in China,

ranking first in population and population density, a few

studies have reported on the source apportionment of

sedimentary PAHs in Shanghai. Ren et al. (2006) reported the

distribution and sources of PAHs from dust collected in

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +86 21 6598 4261.

E-mail address: chenling@tongji.edu.cn (L. Chen).

0048-9697/$ – see front matter © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.12.046

2932

S CI EN CE OF T H E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

Shanghai, and affirmed that vehicle exhaust was the main

source. Liu et al. (2007a) also characterized the PAH sources,

identifying road dust PAHs in central Shanghai areas, and

suggested that road dust PAHs mainly came from the mixing

of traffic and coal combustion and that PAH levels in most

samples in the winter were almost always higher than those

in the summer. Feng et al. (2006) investigated the characteristics of organic matter in PM2.5 in the atmosphere of Shanghai

and found a strong presence of combustion engine exhaust

emissions.

Knowledge regarding the sources and pathways of pollutants in aquatic sediments is important for effective pollution

abatement. While diagnostic ratios of PAHs have been widely

applied to identify sources in various environments (Soclo

et al., 2000; Yunker et al., 2002; Rocher et al., 2004; Zhang et al.,

2004; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006a), their use is limited due

to a lack of reliability. More sophisticated statistical

approaches have been demonstrated, including cluster analysis, principal components analysis (PCA), and chemical

mass balance (CMB). However, there are limitations in

requiring an input of source emission profiles to calculate

source contributions when a CMB model has been used to

identify and quantify sources of pollutants (Duval and

Friedlander, 1981; Li et al., 2001, 2003). PCA, which can provide

information on source contributions, in conjunction with

multivariate linear regression (MLR), has been performed to

identity and apportion PAH sources in the air, soil, and

sediment in many cities (Harrison et al., 1996; Larsen and

Baker, 2003; Li et al., 2006b; Zuo et al., 2007).

In our previous work, we reported the concentrations,

spatial distribution and sources of PAHs in surface sediments

of the Yangtze estuary, Huangpu River and Suzhou River in

Shanghai, China, and identified pyrogenic sources as important contributors of sedimentary PAHs in the Huangpu River

(Liu et al., 2008). The purpose of this work is to further identify

the major sources of sedimentary PAHs in the Huangpu River

by cluster analysis and principal component analysis, and to

carry out quantitative sources apportionment and to discuss

seasonal variations of PAH pollution based on the PCA/MLR.

Methylnaphthalenes and 18 PAHs, including 16 PAHs identified by the US EPA as priority pollutants, were monitored in

surface sediments. A total organic carbon (TOC) analysis was

also carried out to normalize the sedimentary PAH concentrations of Huangpu River to reduce the effect of sediment

property on PAH concentration. The results of this study will

provide valuable information for regulatory actions to

improve the environmental quality of Huangpu River,

Shanghai.

2.

Experimental methods

2.1.

Sample collection and analysis

Eight sampling stations were selected along the Huangpu

River in Fig. 1; details of the sampling stations are listed

elsewhere (Liu et al., 2008). Surface sediment samples were

collected at 8 sampling stations using a grab dredge in April

(spring), August (summer), October (autumn) and December

(winter) of 2006. A total of 32 samples were used in this work.

Surface sediment samples were air-dried in the dark, sieved to

<0.076 mm (200 mesh) after removing stones and residual

roots, and stored at −4 °C until analysis.

16 PAHs characterized by the US EPA as priority pollutants

were analyzed, including naphthalene (Nap), acenaphthylene

(AcNy), fluorene (Fl), acenaphthene (AcNe), phenanthrene

(PhA), anthracene (An), fluoranthene (FlA), pyrene (Py), benz

[a]anthracene (BaA), chrysene (Chy), benzo[b]fluoranthene

(BbF), benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF), benzo[a]pyrene (BaP),

indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene (IP), benzo[ghi]perylene (BghiP), and

dibenz[a,h]anthracene (DBahA). In addition to the 16 priority

PAHs, benzo[e]pyrene (BeP), perylene (Pery), 1-methylnaphthalene and 2-methylnapthalene were also analyzed.

Two isomers of methylnaphthalenes were pooled as total

methylnaphthalenes (MNap).

Sample extraction and cleanup were carried out according

to Method 3540C and Method 3630C published by US EPA

(USEPA, 1996). After extraction and cleanup, samples were

concentrated and adjusted to 1 mL volume for analysis. PAH

analysis was carried out by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a photodiode array detector. Identification of PAHs was based on retention time and the ultraviolet

spectra of PAH standards. The quantification was performed

by the external standard method. The ultraviolet measuring

wavelengths include 218 nm (NaP), 223 nm (MNaP), 226 nm

(AcNe and AcNy), 249 nm (IP), 254 nm (Fl, PhA and An), 266 nm

(Chy), 286 nm (FlA and BaA), 300 nm (BbF, BkF, BaP, DBahA and

BghiP), 330 nm (BeP), 334 nm (Py) and 433 nm (Pery). Detailed

procedures for sample preparation, extraction, cleanup,

measurement and quality control are described elsewhere

(Liu et al., 2007b, 2008). Method detection limits were 1–19 ng/

g-dw, and spiked recoveries of PAHs were 87–113%. All of the

samples taken were analyzed in triplicate, and the relative

standard deviation was less than 20%.

Total organic carbon (TOC) analysis was performed with

the Shimadzu TOC-Vcpn analyzer with the solid sample

module (SSM-5000A). The overall precision of measurements

was less than 3% (n = 3).

Fig. 1 – Sediment sampling locations in the Huangpu River.

2933

S CI EN C E OF TH E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

PCA factor scores and the standardized normal deviation of

total PAH concentrations (normalization first to organic

carbon and then scaled to mean and standard deviation) as

independent and dependent variables, respectively (Larsen

and Baker, 2003). The regression was run using a forward

stepwise method. The standardized regression coefficients

were used to represent the relative contributions from various

sources (Larsen and Baker, 2003; Zuo et al., 2007).

Fig. 2 – Hierarchical dendogram for 18 PAHs in the Huangpu

River sediments using average linkage between groups and

Pearson correlation as measure interval.

2.2.

Statistical analyses

Before statistical analysis of data, we replaced undetectable

values by a random number between zero and the limit of

detection, and eliminated AcNy as it was undetectable in most

of the samples. Different hydraulic conditions at the different

sampling locations lead to different deposition rates and to

different sediment properties, e.g., TOC content and particle

size distribution. Many researchers have indicated that

organic carbon is an important controlling factor of the

sorption of PAHs on sediments (Karickhoff et al., 1979; Wang

et al., 2001; Zakaria et al., 2002). In order to reduce this effect,

we sieved sediment samples to <0.076 mm (200 mesh) before

analysis, and normalized PAH concentrations to TOC contents. At the same time, normalization to TOC produced a

normalized dataset for the following statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses, including the Kolmogorov–Smirnov

(K–S) test, ANOVA, cluster analysis, principal components

analysis, and multivariate linear regression, were performed

using SPSS 13.0 for Windows. The K–S test was carried out to

test the frequency distribution of PAH data, and all of the

variables after normalization to TOC achieved a normal

distribution with P > 0.05. A repeated measures one-way

ANOVA procedure was performed to test the significant

differences of the PAH dataset. The contents of the individual

PAHs were hierarchically clustered using weighted average

linkage between the groups and the Pearson correlation for

the cluster intervals (Zhang et al., 2006). PCA, as a multivariate

analytical tool, was used to reduce the set of original variables

(measured PAH contents in sediment samples) and to extract

a small number of latent factors (principal components) to

analyze the relationships among the observed variables. In

detail, all factors with eigenvalues over 1 were extracted

according to KMO and Bartlett's test of sphericity, and were

rotated using the Varimax method. MLR was conducted using

3.

Results and discussion

3.1.

Source estimates from cluster analysis

Cluster analysis was performed to identify the homogeneous

groups of individual PAHs in the Huangpu River sediments.

The result of the cluster analysis is shown in the hierarchical

dendogram (Fig. 2), which distinguishes the 18 individual

PAHs into three major groups. The first group, which includes

MNap, Nap, Fl and AcNe, belongs to the low molecular weight

PAHs with 2–3 rings or alkyl-substituted PAHs, which are

abundant in petrogenic sources mainly caused by petroleum

spills, e.g., fresh or used crankcase oil, crude and fuel oil (Marr

et al., 1999; Utvik et al., 1999; Dobbins et al., 2006; Gonzalez

et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2006). The second major group is

subdivided into two subgroups. The first subgroup contains

BbF, BkF, BaP, BeP, DBahA and BghiP, which are the high

molecular weight PAHs with 5–6 rings. The second subgroup

consists of PhA, FlA, Py, BaA, Chy and IP, most of which are 4

ring PAHs. Both of these subgroups are usually detected in

pyrogenic source, e.g., combustion of coal, wood, vehicle fuel

and waste tire (Levendis et al., 1998; Zakaria et al., 2002; Wang

et al., 2007). The third major group contains only two

components of An and Pery, and currently has an unknown

source, which is further discussed in the PCA.

3.2.

Diagnostic ratios of PAHs

The relative abundances or diagnostic ratios are useful

indicators of PAH sources because isomer pairs are diluted to

a similar extent upon mixing with natural particulate matter,

and are distributed similarly to other phases as they have

comparable thermodynamic partitioning and kinetic mass

transfer coefficients (Dickhut et al., 2000). Diagnostic ratios of

PAHs, such as the ratio of LMW (2–3 ring PAHs) to HMW (4–6

ring PAHs), An/(PhA + An) and FlA/(FlA + Py), can be used to

identify the possible emission sources, as summarized in

Table 1 – The range of diagnostic ratios for PAHs sources

Diagnostic ratio Petrogenic Pyrogenic

LMW/HMW

>1

<1

An/(PhA + An)

<0.1

>0.1

FlA/(FlA + Py)

<0.4

>0.4

References

Soclo et al. (2000),

Rocher et al. (2004),

Wang et al. (2006)

Yunker et al. (2002),

Zhang et al. (2004),

Li et al. (2006a)

Yunker et al. (2002),

Zhang et al. (2004),

Li et al. (2006a)

2934

S CI EN CE OF T H E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

Fig. 3 – PAH cross plots for the ratios of An/(An + PhA) vs. FlA/

(FlA + Py).

Table 1. The ratios of LMW/HMW in the Huangpu River

sediments range from 0.12 to 0.59 with a mean of 0.33. The

ratio of LMW/HMW is < 1, indicating a predominance of

combustion source (Soclo et al., 2000; Rocher et al., 2004;

Wang et al., 2006). In Fig. 3, the ratios of An/(An + PhA) range

ttfrom 0.12 to 0.39 with a mean of 0.27, and the ratios of FlA/

(FlA + Py) range from 0.39 to 0.57 with a mean of 0.49. These

are similar to measures for combustion, especially coal

combustion of power plants and liquid fossil fuel (vehicle

and crude oil) combustion (Yunker et al., 2002; Zhang et al.,

2004; Li et al., 2006a). Therefore, pyrogenic sources are the

major sources of PAHs in the Huangpu River sediments.

3.3.

Source estimates from principal components analysis

The purpose of PCA is to represent the total variability of the

original PAH data with a minimum number of factors. By

critically evaluating the factor loadings, an estimate of the

chemical source responsible for each factor can be made

(Larsen and Baker, 2003). The rotated factors of 18 normalized

PAHs (by TOC) from the Huangpu River sediments are

presented in Table 2. The three factors account for 83.9% of

the variability in the data. Factor 1, which explains 43.9% of

total variance, is dominated by PhA, FlA, Py, Chy, BaA, BbF,

BkF, BaP, DBahA, IP, BghiP and BeP. Factor 2, contributing

20.1% of total variance, is highly weighted by An and Pery.

Factor 3, which explains 19.9% of total variance, is dominated

by MNap, Nap, Fl and AcNe. The result of PCA is similar to that

of the cluster analysis above. Factor 3, corresponding to the

first group, represents a petrogenic source; Factor 1, corresponding to the second group, represents pyrogenic source

PAHs; and Factor 2, corresponding to the third group,

represents an unknown source. In Table 2, the loadings of

An and Pery are 0.87 and 0.89, respectively. It is unusual to

have An and Pery covary in environmental samples. Pery is a

natural compound formed from biogenic precursors (e.g.,

perylenequinone pigments) during early diagenesis, while

trace concentrations of perylene are generated through

combustion of fossil fuel (Hites et al., 1980; Venkatesan,

1988; Boonyatumanond et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2006). The

biogenic production of An is negligible in comparison to Pery,

because An is susceptible to biogradation (Santos et al., 2008),

hence Pery might be primarily combustion generated. Therefore, Factor 3, namely the third group, is believed to be an

unknown combustion source, although we cannot explain

why An was classified in this group.

According to the cluster analysis, the pyrogenic source can

be subdivided into two subgroups, which represent two kinds

of different pyrogenic sources. However, the results of PCA

cannot differentiate the two subsets of pyrogenic sources,

even if the number of principal components is set as 4. Since

pyrogenic sources of PAHs are the main objectives investigated in order to control PAH pollution in the Huangpu River

sediments, the unknown source can be ignored in this

investigation. We therefore removed data about An and Pery

from the data matrix and performed the PCA again in order to

further investigate the pyrogenic sources of PAHs.

The rotated factors of the 16 PAHs without Pery and An are

shown in Table 3. There are again three factors, accounting for

84.8% of the variability in the data.

The first factor is responsible for 35.0% of the total variance.

This factor is heavily weighted in BkF, BaP, DBahA, BghiP and

BeP, along with moderate loadings for Py, BbF and IP. These PAH

components, the high molecular weight PAHs with 5–6 rings,

basically belong to the first subgroup of Group 2 of the cluster

analysis. The source this factor represents appears to be road

dust collected from the Shanghai urban area (Ren et al., 2006; Liu

et al., 2007a) and is vehicular (gasoline and diesel) in nature

(Harrison et al., 1996; Larsen and Baker, 2003; Ye et al., 2006; Zuo

et al., 2007). BghiP has been identified as a tracer of auto

emissions because it was found to be enriched in a traffic tunnel

along with BaP (Harrison et al., 1996; Larsen and Baker, 2003;

Table 2 – Rotated component matrix of 18 PAHs from the

Huangpu River sediment a

No.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

PAH

MNap

Nap

Fl

AcNe

PhA

An

FlA

Py

Chy

BaA

BbF

BkF

BaP

DBahA

IP

BghiP

BeP

Pery

Estimated source

Variance (%)

a

b

Principal components

1

2

3

0.03

0.03

0.30

0.32

0.69

0.20

0.90

0.91

0.88

0.93

0.82

0.72

0.74

0.68

0.79

0.70

0.76

− 0.17

−0.08

−0.10

0.46

0.35

0.10

0.87

−0.26

0.23

−0.12

−0.04

0.34

0.36

0.58

0.59

0.18

0.64

0.45

0.89

0.95 b

0.94

0.74

0.82

0.49

0.08

0.18

0.18

0.22

0.15

0.10

−0.20

−0.12

−0.17

0.18

0.15

0.21

0.14

Pyrogenic

43.9

Unknown

20.1

Petrogenic

19.9

Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Bold loadings > 0.70.

S CI EN C E OF TH E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

Table 3 – Rotated component matrix of 16 PAHs from the

Huangpu River sediment a

No.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

PAH

MNap

Nap

Fl

AcNe

PhA

FlA

Py

Chy

BaA

BbF

BkF

BaP

DBahA

IP

BghiP

BeP

Estimated source

Variance (%)

a

b

Principal components

1

2

3

− 0.17

− 0.19

0.41

0.34

0.36

0.23

0.65

0.31

0.43

0.69

0.77

0.91

0.88

0.56

0.88

0.78

0.13

0.15

0.11

0.17

0.59

0.92

0.68

0.86

0.85

0.55

0.32

0.30

0.24

0.58

0.28

0.39

0.93 b

0.91

0.80

0.87

0.49

0.12

0.21

0.18

0.13

0.15

− 0.11

− 0.01

− 0.06

0.21

0.26

0.29

Traffic

35.0

Coal

27.0

Petrogenic

22.8

Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Bold loadings > 0.70.

(Levendis et al., 1998). Some researchers have also reported PhA,

FlA, Py as predominant in coal combustion profiles (Harrison

et al., 1996; Zuo et al., 2007). In Shanghai, coal is the most

important energy source and is used widely for industrial and

domestic purposes, especially in the steel and power industry.

The Shanghai municipal electric power supply is mainly derived

from coal-burning power plants. It is reasonable to assign this

factor to coal combustion.

The third factor is responsible for 22.8% of the total

variance, and is heavily weighted in MNap, Nap, Fl and

AcNe, the same as the result of the former PCA. This factor

is suggested to be indicative of volatilization or spill of

petroleum-related products (Marr et al., 1999; Utvik et al.,

1999; Zakaria et al., 2002; Luca et al., 2004; Dobbins et al., 2006;

Gonzalez et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2006), e.g.,

from the waterway transportation industry. This factor is

believed to be the petrogenic source of PAHs.

In general, the first PCA of PAH data shows that there are

three PAH sources in the Huangpu River sediments, namely

pyrogenic, petrogenic and an unknown combustion source.

The second PCA of data without Pery and An (the unknown

source) divides the pyrogenic source of PAHs into two subsets,

one traffic-related and the other due to coal combustion.

3.4.

Boonyatumanond et al., 2007). The higher level of BkF relative to

other PAHs is suggested to indicate diesel vehicles (Venkataraman et al., 1994; Larsen and Baker, 2003). On the other hand, this

factor is moderately weighted in IP, which has also been found

in both diesel and gas engine emissions (May and Wise, 1984;

Larsen and Baker, 2003) and gasoline vehicle soot (Boonyatumanond et al., 2007). Therefore, this factor is selected to

represent the traffic-related source of PAHs.

The second factor is responsible for 27.0% of the total

variance. This factor is predominately composed of FlA, Chy

and BaA (4-ring PAHs) with moderate loadings of PhA, Py, BbF

and IP. There are similar PAH components between this factor

and the second subgroup of Group 2 in the cluster analysis. The

literature reports that 4-ring PAHs are abundant in the road dust

in Bangkok city (Boonyatumanond et al., 2007) and Kuala

Lumpur city (Zakaria et al., 2002), but the abundance of 4-ring

PAHs is lower in the road dust in Shanghai city (Ren et al., 2006;

Liu et al., 2007a) compared with these. The ratio of PAHs (4 rings)

to PAHs (5–6 rings), abbreviated PAHs(4)/PAHs(5 + 6), is greater

than 1 in Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur, according to the PAH

profiles of road dust (Zakaria et al., 2002; Boonyatumanond et al.,

2007). However, PAHs(4)/PAHs(5+ 6) is 0.3–0.8 in the central

Shanghai area (Liu et al., 2007a) and 0.5–1.1 in the Shanghai

urban area (Ren et al., 2006). In this paper, we show that PAHs(4)/

PAHs(5 + 6) in the sediment, 0.8–1.4 with a mean of 1.1, is more

than that in the road dust from Shanghai. This indicates that

there should be an additional PAH source (not traffic-related)

leading to the higher ratio of PAHs(4)/PAHs(5 + 6). Duval and

Friedlander (1981) considered PhA, FlA, Py, BaA and Chy as

markers of coal combustion. According to PAH data from the

combustion of pulverized coal and tire crumbs at 1000 °C (near

the temperature of coal combustion in the coal-burning power

plant), PhA, FlA and Py are the dominant PAHs with lower

concentrations of 5–6 ring PAHs detected in furnace effluents

2935

Contribution of PAH sources

The ultimate goal of source apportionment is to determine the

percent contribution of different PAH sources for a given

samples. We unveiled the major sources of sedimentary PAHs

in the Huangpu River using diagnostic ratios, cluster analysis

and PCA. We then calculated the percent contributions of the

major sources using multivariate linear regression (MLR) from

the PCA factor scores and the standardized normal deviation

of total PAH concentrations as our independent and dependent variables, respectively. Several authors (Harrison et al.,

1996; Larsen and Baker, 2003; Zuo et al., 2007) have reported

applying PCA/MLR to apportion sources of PAHs in the urban

atmosphere and surface soils.

The mean percent contribution of source i is the ratio of the

regression coefficient for factor i to the sum of all the

regression coefficients, according to the description in the

literature (Larsen and Baker, 2003). The factor scores are from

the result of PCA without Pery and An. The R squared value for

MLR is 0.983 and the P values for the regression coefficients

are less than 0.05. Thus, the mean contribution percents are

40% for the vehicular source, 36% for the coal combustion

source, and 24% for the petrogenic source.

The traffic-related source (40%) is the first contributor to

the PAHs. There are two origins of traffic-related PAHs in the

Huangpu River. For one thing, traffic-related PAHs in road dust

can enter the sediments through urban runoff (Zakaria et al.,

2002; Murakami et al., 2005; Boonyatumanond et al., 2006,

2007). In recent decades, a rapid increase in motor vehicles in

Shanghai has aggravated PAH pollution in the Huangpu River

sediments. For example, the number of taxis increased from

11,298 in 1990 to 48,022 in 2006 (Yin, 2007). Exhaust from cargo

vessels and passenger ferries in the Huangpu River also plays

an important role as a PAH contributor, and should not be

ignored in the discussion of sedimentary PAHs. In fact, cargo

vessels are responsible for most coal transportation to coal-

2936

S CI EN CE OF T H E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

burning power plants located along the Huangpu River.

Passenger ferries also still serve the public, despite the rapid

development of traffic facilities across the Huangpu River.

Furthermore, compared with automobiles, more PAHs are

emitted from vessels and ferries because most of them are not

equipped with catalytic converters (Rogge et al., 1993).

Coal combustion (36%) is the second contributor to PAHs. In

recent years, most coal in Shanghai is used to generate electric

power due to a control on the emission of SO2, NOx and

suspended particles. However, coal consumption in the power

industry in Shanghai is continually increasing, from 3.0 million

tons in 1980 to 10.6 million tons in 1990 to 25.0 million tons in

2005 (SLCO, 2008a), causing a high percent contribution of coal

combustion. Several large-scale coal-burning power plants are

located along the Huangpu River, leading to an easy input of

coal combustion PAHs into the Huangpu River.

Petrogenic sources (24%) form the third contributor to PAHs.

Petrogenic sources include crude oil and refined products (e.g.,

crude and fuel oil). Zakaria et al. (2002) thought that there were

two major input routes to aquatic environments, namely

(1) spillage and dumping of waste crankcase oil and (2) leakage

of crankcase oils from vehicles onto road surfaces, with

subsequent washout by street runoff. In China, waste crankcase

oil has been included in the national list of hazardous wastes,

and its dumping is illegal and punished by law. In general, most

used crankcase oil is recycled by garages in vehicle maintenance. However, if crankcase oil is replaced in private, it may

be improperly stored or deposited, allowing for indiscriminate

spillage to the ground and streets or even for oil to be poured

directly into drains or the water environment, as there is

currently no efficient recycling program for used crankcase oil in

Shanghai. In addition, vessel maintenance and fuel supply may

lead to input of petrogenic PAHs into the sediment.

3.5.

Seasonal variation

Contamination of the bottom sediment is often a gradual

process. However, the repeated measures one-way ANOVA

results indicate a distinct seasonal variation, that is, the

concentrations of total PAHs are significantly higher in the

spring than in the other seasons (at the significant level of

0.05). The mean concentrations of total PAHs in different

seasons are listed in Table 4. In order to further investigate the

causes, the contributions of three important sources in

different seasons are calculated in Table 4, according to the

following formula of Larsen and Baker (2003).

Contribution of source i ðng=mg TOCÞ = mean

X Bi + Bi dPAHs FSi

Bi =

X

16

PAHs

where Bi/ΣBi is the ratio of the regression coefficient for factor i

to the sum of all of the regression coefficients, FSi is the factor

score for factor i, and δPAHs is the standard deviation of total

PAH concentrations after normalization to organic carbon.

A higher concentration of total PAHs in the spring results

from a higher contribution of coal combustion and petrogenic

sources. The repeated measures one-way ANOVA results

suggest that the contributions of coal combustion in spring are

significantly higher than those in the summer and autumn, and

that those of the petrogenic source in spring are higher than in

the other seasons (at the significant level of 0.05). As for coal

combustion, 71.3 BkW h of electric power were generated during

2006, most from coal-burning power plants in Shanghai (SMEPC,

2008). This indicates that the consumption of electric power can

reflect the consumption of coal in Shanghai. Statistical data in

Table 4 show that the consumption of electric power in the

summer and winter (19.9 and 18.4 BkW h) is more than that in

the spring and autumn (16.4 and 16.9 BkW h). This results in

higher PAH pollution from coal combustion in the summer and

winter, which disagrees with the result of PAH source apportionment (higher PAH pollution in the spring). There are two

reasons leading to this disagreement. For one thing, winter in

Shanghai is a dry season with 102 mm of average seasonal

rainfall (~9% of average annual rainfall), and a rainy period

follows from April 15th to May 15th with ~14% of average annual

rainfall (157 mm) (SLCO, 2008b), leading to PAHs in the air and

soil generated in the winter being brought into the Huangpu

River in the spring through rainfall and surface runoff. In

addition, as a coastal city, Shanghai is affected by summer

monsoons, which bring in clean oceanic winds in the summer

that dilute local air pollutants (Feng et al., 2006); PAHs from coal

combustion are typical air pollutants. As for petrogenic PAHs,

the lower temperature in the winter and spring is an important

factor, because low temperature decreases the evaporation of

petrogenic PAHs (Feng et al., 2006). Meanwhile, rainfall in the

spring brings particles with petrogenic and coal combustion

PAHs into the Huangpu River. For the traffic-related source, the

contribution in the spring is significantly lower than that in

Table 4 – Seasonal differentiation of PAHs sources

Season a

Spring

Summer

Autumn

Winter

a

Temperature

(°C) b

Electric power

(BkW h) c

Total PAHs

(ng/mg-TOC) d

8.4–19

23–27

12–23

3.6–6.2

16.4

19.9

16.9

18.4

137.2

102.5

105.1

103.4

Pollution source of PAHs (ng/mg-TOC) e

Traffic

Coal combustion

Petrogenic

40.2

33.7

57.2

48.8

54.1

34.5

33.1

40.1

35.3

28.7

21.1

21.6

Spring in Shanghai is March–May, summer is June–August, autumn is September–November, and winter is December–next February.

Data were official statistics from 1951 to 1990 (SLCO, 2008b).

c

Seasonal loads of Shanghai electric power grid, and unit is billion kilowatt-hours. Data from Match 2006 to February 2007 were provided by

Shanghai Municipal Electric Power Company (SMEPC, 2008).

d

Mean of total PAHs concentrations of 8 sampling locations; total PAHs is sum of observed concentrations of 16 PAHs listed in Table 3.

e

Mean source contributions of 8 sampling locations.

b

S CI EN C E OF TH E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

2937

variate analysis methods show that the contributions of coal

combustion, traffic-related pollution and spill of oil products

are dominant in the Huangpu River sediments. The results of

diagnostic ratios show that pyrogenic sources are the major

source of PAHs. PCA/MLR further apportions the sources'

contributions, and the results show that the contributions of

coal combustion, traffic-related pollution and spill of oil

product are 40%, 36% and 24%, respectively. The pyrogenic

sources (coal combustion and traffic-related pollution) contribute 76% of anthropogenic PAHs to the Shanghai sediments.

Energy consumption is a predominant reason for PAH pollution in Shanghai.

Sedimentary PAH pollution is significantly higher in the

spring than in the other seasons. The higher concentrations in

the spring are attributed to the higher contribution of coal

combustion and petrogenic sources. Rainfall, monsoon and

temperature play important roles in producing the distinct

seasonal variation of sedimentary PAHs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (Nos. 20477030 and 40601095) and the

Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (Nos.

05JC14059 and 04JC14072).

REFERENCES

Fig. 4 – Score plots of principal components analysis.

the autumn (at the significant level of 0.05). Li et al. (2006b)

suggested that when the Chinese traditional Spring Festival

takes place in the spring with few vehicles and vessels on the

move (people taking vacation out of the city), the traffic-related

pollution is low.

Factor score plots of principal components analysis also

show a seasonal variation of sedimentary PAHs in the Huangpu

River. Fig. 4a and b shows score plots of PC1 vs. PC2 and PC1 vs.

PC3, respectively. Fig. 4 illustrates that samples collected in the

spring and autumn are clustered in respective areas of the

diagram. Samples collected in the autumn have higher traffic

factor scores (PC1) and lower factor scores of coal combustion

(PC2) and petrogenic sources (PC3). On the other hand, scores in

the spring are higher in the coal combustion (PC2) and

petrogenic factors (PC3), and lower in the traffic factor (PC1).

This indicates that there is a distinct variation between spring

and autumn for the contributions of PAH sources.

4.

Conclusion

The combination of cluster analysis and principal component

analysis is effective for identifying PAHs sources. Both multi-

Boonyatumanond R, Wattayakorn G, Togo A, Takada H. Distribution

and origins of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in

riverine, estuarine, and marine sediments in Thailand. Mar

Pollut Bull 2006;52:942–56.

Boonyatumanond R, Murakami M, Wattayakorn G, Togo A, Takada

H. Sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in street

dust in a tropical Asian mega-city, Bangkok, Thailand. Sci Total

Environ 2007;384:420–32.

Dickhut RM, Canuel EA, Gustafson KE, Liu K, Arzayus KM, Walker

SE, et al. Automotive sources of carcinogenic polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons associated with particulate matter in

the Chesapeake Bay Region. Environ Sci Technol

2000;34:4635–40.

Dobbins RA, Fletcher RA, Benner Jr BA, Hoeft S. Polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons in flames, in diesel fuels, and in diesel emissions.

Combust Flame 2006;144:773–81.

Duval MM, Friedlander SK. Source resolution of polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons in the Los Angeles atmospheres. Application of a

CMB with first order decay. Washington, DC: U.S. Government

Printing Office; 1981. U.S. EPA Report EPA-600/2-81-161.

Feng J, Chan CK, Fang M, Hu M, He L, Tang X. Characteristics of

organic matter in PM2.5 in Shanghai. Chemosphere

2006;64:1393–400.

Gonzalez JJ, Vinas L, Franco MA, Fumega J, Soriano JA, Grueiro G, et al.

Spatial and temporal distribution of dissolved/dispersed

aromatic hydrocarbons in seawater in the area affected by the

Prestige oil spill. Mar Pollut Bull 2006;53:250–9.

Harrison RM, Smith DJT, Luhana L. Source apportionment of

atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons collected from

an urban location in Birmingham, U.K. Environ Sci Technol

1996;30:825–32.

Hites RA, Laflamme RF, Windsor Jr JG, Farrington JW, Deuser WG.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in an anoxic sediment core

2938

S CI EN CE OF T H E T OTAL EN V I RO N M EN T 4 0 7 ( 2 0 09 ) 29 3 1–2 93 8

from the Pettaquamscutt River. Geochim Cosmochim Acta

1980;44:873–8.

Karickhoff SW, Brown DS, Scott TA. Sorption of hydrophobic

pollutants on natural sediments. Water Res 1979;13:241–8.

Larsen III RK, Baker JE. Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons in the urban atmosphere: a comparison of three

methods. Environ Sci Technol 2003;37:1873–81.

Levendis YA, Atal A, Carlson JB. On the correlation of CO and PAH

emissions from the combustion of pulverized coal and waste

tires. Environ Sci Technol 1998;32:3767–77.

Li K, Christensen ER, Van Camp RP, Imamoglu I. PAHs in dated

sediments of Ashtabula River, Ohio, USA. Environ Sci Technol

2001;35:2896–902.

Li A, Jang J-K, Scheff PA. Application of EPA CMB8.2 model for

source apportionment of sediment PAHs in Lake Calumet,

Chicago. Environ Sci Technol 2003;37:2958–65.

Li G, Xia X, Yang Z, Wang R, Voulvoulis N. Distribution and sources

of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the middle and lower

reaches of the Yellow River, China. Environ Pollut

2006a;144:985–93.

Li J, Zhang G, Li XD, Qi SH, Liu GQ, Peng XZ. Source seasonality of

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a subtropical city,

Guangzhou, South China. Sci Total Environ 2006b;355:145–55.

Liu M, Cheng SB, Ou DN, Hou LJ, Gao L, Wang LL, et al.

Characterization, identification of road dust PAHs in central

Shanghai areas, China. Atmos Environ 2007a;41:8785–95.

Liu Y, Chen L, Tang Y, Huang Q, Zhao J. Determination of trace

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of

Huangpu River by high performance liquid chromatography.

Chin J Chromatogr 2007b;25:356–61.

Liu Y, Chen L, Zhao JF, Huang QH, Zhu ZL, Gao HW. Distribution

and source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface

sediments of rivers and an estuary in Shanghai, China. Environ

Pollut 2008;154:298–305.

Luca GD, Furesi A, Leardi R, Micera G, Panzanelli A, Piu PC, et al.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons assessment in the sediments

of the Porto Torres Harbor (Northern Sardinia, Italy). Mar Chem

2004;86:15–32.

Marr LC, Kirchstetter TW, Harley RA, Miguel AH, Hering SV,

Hammond SK. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons in motor vehicle fuels and exhaust emissions.

Environ Sci Technol 1999;33:3091–9.

May WE, Wise SA. Liquid chromatographic determination of

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in air particulate extracts.

Anal Chem 1984;56:225–32.

Murakami M, Nakajima F, Furumai H. Size- and density-distributions

and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban road

dust. Chemosphere 2005;61:783–91.

NRC. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: evaluation of sources and

effects. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1983.

Ren Y, Zhang Q, Chen J. Distribution and source of polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) on dust collected in Shanghai,

People's Republic of China. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol

2006;76:442–9.

Rocher V, Azimi S, Moilleron R, Chebbo G. Hydrocarbons and

heavy metals in the different sewer deposits in the Le Marais'

catchment (Paris, France): stocks, distributions and origins. Sci

Total Environ 2004;323:107–22.

Rogge WF, Hildemann LM, Mazurek MA, Cass GR, Simoneit BRT.

Sources of fine organic aerosol. 2. Noncatalyst and

catalyst-equipped automobiles and heavy-duty diesel trucks.

Environ Sci Technol 1993;27:636–51.

Santos EC, Jacques RJS, Bento FM, Peralba MDCR, Selbach PA, Sa

ELS, et al. Anthracene biodegradation and surface activity by

an iron-stimulated Pseudomonas sp. Bioresour Technol

2008;99:2644–9.

SLCO (Shanghai Local Chronicle Office). 2008a. from:http://www.

shtong.gov.cn/node2/node2245/node4441/node58151/index.

html,2008, April.

SLCO (Shanghai Local Chronicle Office). 2008b. from http://www.

shtong.gov.cn/node2/node2245/node65523/node65528/

node65574/node65678/userobject1ai61022.html,2008, April.

SMEPC (Shanghai Municipal Electric Power Company). 2008. from:

http://sd.smepc.com/list_1_11086960665005265648.htm,2008,

April.

Soclo HH, Garrigues P, Ewald M. Origin of polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coastal marine sediments: case studies

in Cotonou (Benin) and Aquitaine (France) areas. Mar Pollut

Bull 2000;40:387–96.

USEPA. Test methods for evaluating solid waste, physical/chemical

methods SW-846. Washington, DC, USA: Office of solid waste

and emergency response; 1996.

Utvik TIR, Durell GS, Johnsen S. Determining produced water

originating polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in North Sea

waters: comparison of sampling techniques. Mar Pollut Bull

1999;38:977–89.

Venkataraman C, Lyons JM, Friedlander SK. Size distributions of

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and elemental carbon. 1.

Sampling, measurement methods, and source characterization.

Environ Sci Technol 1994;28:555–62.

Venkatesan MI. Occurrence and possible sources of perylene in

marine sediments — a review. Mar Chem 1988;25:1-27.

Wang X-C, Zhang Y-X, Chen RF. Distribution and partitioning of

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in different size

fractions in sediments from Boston Harbor, United States. Mar

Pollut Bull 2001;42:1139–49.

Wang X-C, Sun S, Ma H-Q, Liu Y. Sources and distribution of

aliphatic and polyaromatic hydrocarbons in sediments of

Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, China. Mar Pollut Bull 2006;52:129–38.

Wang Z, Li K, Lambert P, Yang C. Identification, characterization and

quantitation of pyrogenic polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons and

other organic compounds in tire fire products. J Chromatogr A

2007;1139:14–26.

Ye B, Zhang Z, Mao T. Pollution sources identification of polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons of soils in Tianjin area, China.

Chemosphere 2006;64:525–34.

Yin Y. Shanghai yearbook (2007). Shanghai, China: Shanghai

Nianjian Press; 2007.

Yunker MB, Macdonald RW, Vingarzan R, Mitchell HR, Goyette D,

Sylvestre S. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: a critical appraisal

of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org

Geochem 2002;33:489–515.

Zakaria MP, Takada H, Tsutsumi S, Ohno K, Yamada J, Kouno E, et al.

Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in rivers

and estuaries in Malaysia: a widespread input of petrogenic

PAHs. Environ Sci Technol 2002;36:1907–18.

Zedeck MS. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review. J Environ

Pathol Toxicol 1980;3:537–67.

Zhang Z, Huang J, Yu G, Hong H. Occurrence of PAHs, PCBs and

organochlorine pesticides in the Tonghui River of Beijing,

China. Environ Pollut 2004;130:249–61.

Zhang HB, Luo YM, Wong MH, Zhao QG, Zhang GL. Distributions

and concentrations of PAHs in Hong Kong soils. Environ Pollut

2006;141:107–14.

Zuo Q, Duan YH, Yang Y, Wang XJ, Tao S. Source apportionment of

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface soil in Tianjin,

China. Environ Pollut 2007;147:303–10.