Learning to Teach in a Different Culture

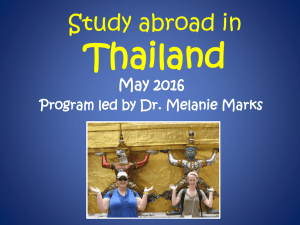

advertisement