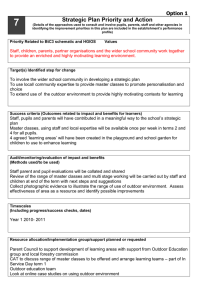

Teaching in nature - Scottish Natural Heritage

advertisement