Russell`s Theory of Definite Descriptions

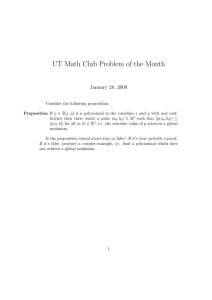

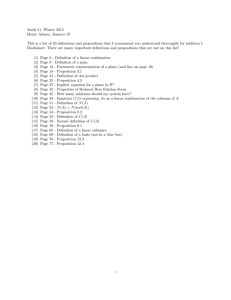

advertisement